Print This Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2012 Winners List

® 2012 Winners List Category 1: American-Style Wheat Beer, 23 Entries Category 29: Baltic-Style Porter, 28 Entries Gold: Wagon Box Wheat, Black Tooth Brewing Co., Sheridan, WY Gold: Baltic Gnome Porter, Rock Bottom Denver, Denver, CO Silver: 1919 choc beer, choc Beer Co., Krebs, OK Silver: Battle Axe Baltic Porter, Fat Heads Brewery, North Olmsted, OH Bronze: DD Blonde, Hop Valley Brewing Co., Springfield, OR Bronze: Dan - My Turn Series, Lakefront Brewery, Milwaukee, WI Category 2: American-Style Wheat Beer With Yeast, 28 Entries Category 30: European-Style Low-Alcohol Lager/German-Style, 18 Entries Gold: Whitetail Wheat, Montana Brewing Co., Billings, MT Silver: Beck’s Premier Light, Brauerei Beck & Co., Bremen, Germany Silver: Miners Gold, Lewis & Clark Brewing Co., Helena, MT Bronze: Hochdorfer Hopfen-Leicht, Hochdorfer Kronenbrauerei Otto Haizmann, Nagold-Hochdorf, Germany Bronze: Leavenworth Boulder Bend Dunkelweizen, Fish Brewing Co., Olympia, WA Category 31: German-Style Pilsener, 74 Entries Category 3: Fruit Beer, 41 Entries Gold: Brio, Olgerdin Egill Skallagrimsson, Reykjavik, Iceland Gold: Eat A Peach, Rocky Mountain Brewery, Colorado Springs, CO Silver: Schönramer Pils, Private Landbrauerei Schönram, Schönram, Germany Silver: Da Yoopers, Rocky Mountain Brewery, Colorado Springs, CO Bronze: Baumgartner Pils, Brauerei Jos. Baumgartner, Schaerding, Austria Bronze: Blushing Monk, Founders Brewing Co., Grand Rapids, MI Category 32: Bohemian-Style Pilsener, 62 Entries Category 4: Fruit Wheat Beer, 28 Entries Gold: Starobrno Ležák, -

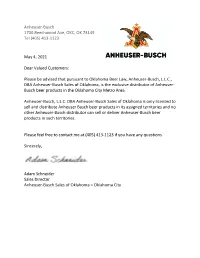

Ss22-C223031 Sole Source Documentation

Anheuser-Busch 1700 Beechwood Ave, OKC, OK 73149 Tel (405) 413-1123 May 4, 2021 Dear Valued Customers: Please be advised that pursuant to Oklahoma Beer Law, Anheuser-Busch, L.L.C., DBA Anheuser-Busch Sales of Oklahoma, is the exclusive distributor of Anheuser- Busch beer products in the Oklahoma City Metro Area. Anheuser-Busch, L.L.C. DBA Anheuser-Busch Sales of Oklahoma is only licensed to sell and distribute Anheuser Busch beer products in its assigned territories and no other Anheuser-Busch distributor can sell or deliver Anheuser-Busch beer products in such territories. Please feel free to contact me at (405) 413-1123 if you have any questions. Sincerely, Adam Schneider Sales Director Anheuser-Busch Sales of Oklahoma – Oklahoma City Anheuser-Busch Sales of Oklahoma Q2 2021 OFF PREMISE PRICE SHEET - OKC Effective: 4/5/21-7/4/21 Updated 3/16/21 ABSO BRAND PACK SIZE SIZE CARRIER PACK COUNT FRONTLINE DISCOUNT EDLP UNIT COST UPC CODE CODE *Rita's* Rita with a Twist of BL Lime. 8.0% ABV Ritas Lime-A-Rita 12PK 8OZ CAN 2$ 25.40 $ 3.40 $ 22.00 $ 11.00 0-18200-19987-5 10513 Ritas Lime-A-Rita 12PK 25OZ CAN 12$ 27.49 $ 3.49 $ 24.00 $ 2.00 0-18200-25014-9 16825 Ritas Mang-O-Rita 12PK 8OZ CAN 2$ 25.40 $ 3.40 $ 22.00 $ 11.00 0-18200-22989-3 26834 Ritas Mang-O-Rita 12PK 25OZ CAN 12$ 27.49 $ 3.49 $ 24.00 $ 2.00 0-18200-25533-5 16826 Ritas Straw-Ber-Rita 12PK 8OZ CAN 2$ 25.40 $ 3.40 $ 22.00 $ 11.00 0-18200-20993-2 10531 Ritas Straw-Ber-Rita 12PK 25OZ CAN 12$ 27.49 $ 3.49 $ 24.00 $ 2.00 0-18200-25505-2 16827 Ritas Water-Melon-Rita 12PK 8OZ CAN 2$ 25.40 -

Cocktails Wine

Cocktails campfire sling 11 forager’s gimlet 14 *Whiskey, smoked maple syrup, chocolate *Gin, blueberry rosemary cordial, fresh bitters, burnt orange oil lime, torched rosemary fall bay whiskey sour 11 camp margarita 14 Bourbon, fresh lemon juice, simple syrup, Reposado, Luxardo, Honeydew Jalapeno egg white**, hot cinnamon bitters Shrub, fresh lime, fresh orange, melon ball ann-apple-is 13 a2n 15 *Vodka, fresh green apple juice, Dark rum, *Navy strength rum, fresh fresh lemon juice, cinnamon sugar rim pineapple, fresh orange, campari, Navy Hill soda float boozy slushies *denotes regional spirits Ask your bartender for the daily flavors Wine By the Glass sparkling Cava Brut, Poema, Catalonia, Spain NV .................................................... 8 rosé Pinot Noir Rosé, SeaGlass, Monterey, CA, US (2018) ....................................... 8 white Pinot Gris, Erath Vineyards, OR, US (2018) .............................................. 10 Saira Albarino, Raimat, Catalonia, Spain (2018) ......................................... 10 Sauvignon Blanc, Villa Maria, Marlborough, New Zealand (2018) ............................ 8 Chardonnay, Barboursville Vineyards, VA, US (2017) ...................................... 12 red Pinot Noir, Z. Alexander Brown, CA, US (2015) .......................................... 10 Cab Franc, Ox-Eye Vineyards, Shenandoah Valley, VA, US (2016) ........................... 14 Blend, Troublemaker, Central Coast, CA, US (NV) ......................................... 12 Malbec, Catena Zapata Vineyard, Mendoza, -

Bijlage – Overzicht Medaillewinnaars AB Inbev Medaillewinnaar World Beer Awards 2018 Bierstijl Medaille Hertog Jan: Grand Pres

Bijlage – overzicht medaillewinnaars AB InBev Medaillewinnaar World Beer Awards 2018 Bierstijl Medaille Hertog Jan: Grand Prestige Vintage Barley Wine Country Winner Hertog Jan: Dubbel Belgian Style Dubbel Country Winner Hoegaarden: Rosee Flavoured (Fruit & Vegetable) Silver Medal Franziskaner Alkoholfrei Blutorange Flavoured (Low Alcohol) Country Winner Franziskaner Alkoholfrei Zitrone 0,0% Flavoured (Low Alcohol) Silver Medal Hertog Jan: Grand Prestige Vatgerijpt 2017 Goose Island Flavoured (Wood Age) Country Winner Hertog Jan: Grand Prestige Vatgerijpt 2017 Bourbon Flavoured (Wood Age) Gold Medal Birra del Borgo: ReAle Extra IPA American Style Country Winner Jupiler pils Lager Classic Pilsner Country Winner Beck's Pils: FRISCH. PUR. ECHT Lager Classic Pilsner Bronze Medal Löwenbräu: Original Hell Bronze Medal Lager Helles Beck's Gold: FRISCH. MILD. ECHT International Lager Country Winner Hertog Jan: Enkel Lager Seasonal Country Winner Leffe: Ambree Pale Belgian style Ale Silver Medal Julius Pale Belgian Style Strong Bronze Medal Hertog Jan: Arcener Tripel Pale Belgian Style Tripel Country Winner Leffe: D'ete Pale Seasonal Silver Medal Brewery Bosteels: Deus Specialty Beers Brut Beers Country Winner Hertog Jan: Grand Prestige Vatgerijpt 2018 Bourbon vanilla Specialty Beers Experimental Country Winner Hoegaarden: Rosee 0.0 Wheat Beer Alcohol Free Silver Medal Franziskaner Alkoholfrei: Alkoholfreies Weißbier Wheat Beer Alcohol Free Silver Medal Hertog Jan: Weizener Wheat Beer Belgian style Witbier Country Winner Franziskaner Dunkel: Dunkles -

Anheuser-Busch Inbev

Our Dream: Anheuser-Busch InBev Annual Report 2014 1 ABOUT ANHEUSER-BUSCH INBEV Best Beer Company Bringing People Together For a Better World Contents 1 Our Manifesto 2 Letter to Shareholders 6 Strong Strategic Foundation 20 Growth Driven Platforms 36 Dream-People-Culture 42 Bringing People Together For a Better World 49 Financial Report 155 Corporate Governance Statement Open the foldout for an overview of our financial performance. A nheuser-Busch InBev Annual / 2014 Report Anheuser-Busch InBev 2014 Annual Report ab-inbev.com Our Dream: Anheuser-Busch InBev Annual Report 2014 1 ABOUT ANHEUSER-BUSCH INBEV Best Beer Company Bringing People Together For a Better World Contents 1 Our Manifesto 2 Letter to Shareholders 6 Strong Strategic Foundation 20 Growth Driven Platforms 36 Dream-People-Culture 42 Bringing People Together For a Better World 49 Financial Report 155 Corporate Governance Statement Open the foldout for an overview of our financial performance. A nheuser-Busch InBev Annual / 2014 Report Anheuser-Busch InBev 2014 Annual Report ab-inbev.com Anheuser-Busch InBev Annual Report 2014 1 ABOUT ANHEUSER-BUSCH INBEV About Revenue was Focus Brand volume EBITDA grew 6.6% Normalized profit Net debt to EBITDA 47 063 million USD, increased 2.2% and to 18 542 million USD, attributable to equity was 2.27 times. Anheuser-Busch InBev an organic increase accounted for 68% of and EBITDA margin holders rose 11.7% Driving Change For of 5.9%, and our own beer volume. was up 25 basis points in nominal terms to Anheuser-Busch InBev (Euronext: ABI, NYSE: BUD) is the leading AB InBev’s dedication to heritage and quality originates from revenue/hl rose 5.3%. -

Pricebook Creator

���� OLYMPICDISTRIBUTING EAGLE Locally based, family-owned sinw 19.54 BEER, PACKAGE, WINE, SPIRITS MIXERS & NON-A[COHOlIG PRICE BOOK July 2021 Proudly serving South King, Pierce, Thurston, Kitsap, Mason, Grays Harbor & Pacific Counties. *Not all products available in all areas. Please check withyour sales rep for producta vailable in your area. The prices reflected in the Olympic Eagle Price Books are for WSLCB licensed retailers only and are subject to change without notice. Service exceeding customer expectations. Table of Contents - Mixers TASTE OF FLORIDA MIXERS 1 TOF BLUE CURACAO PET 1 TOF GREEN APPLE NR 1 TOF GRENADINE PET 1 TOF LIME JUICE PET 1 TOF MARGARITA MIX PET 1 TOF MED BLOODY MARY NR 1 TOF PEACH MIX NR 1 TOF PINA COLADA PET 1 TOF SOUR MIX PET 1 TOF SPICY BLOODY MARY NR 1 TOF STRAWBERRY PUREE PET 1 TOF TRIPLE SEC PET 1 Table of Contents - Package BUD ICE 3 KING COBRA 7 LEFFE 10 BUD ICE 3 KING COBRA 7 LEFFE BLONDE 10 BUD LIGHT 3 LANDSHARK 7 PATAGONIA CERVEZA 10 BUD LIGHT 3 LAND SHARK LAGER 7 PATAGONIA BOHEMIAN PILSNER 10 BUD LIGHT CHELADA 3 MD 20/20 7 PATAGONIA CERVEZA PILSNER 10 BUD LIGHT CHELADA 3 MD 20/20 ISLAND PINEAPPLE 7 SPATEN 10 BUD LIGHT CHELADA FUEGO 3 MD 20/20 SWEET BLUE RASPBERRY 7 SPATEN OKTOBERFEST 10 BUD LIGHT CHELADA MANGO 3 MD 20/20 TANGY ORANGE 7 ST. PAULI GIRL 10 BUD LIGHT LEMONADE 3 MICHELOB 7 ST PAULI GIRL 10 BUD LIGHT LEMONADE 3 MICHELOB 7 ST. PAULI NON-ALCOHOL 10 BUD LIGHT LEMONADE VARIETY PK 3 MICHELOB AMBERBOCK 7 ST PAULI GIRL N.A. -

FROM the GRILL STEAK FRITES 160Gr Lakenvelder Beef, Artisan Fries, Pasta Béarnaise & Green Leaf Salad

evening menu • PLATES & APPETISERS • Experience our City vibes CHARCUTERIE As a famous Haarlem garden architect and real Burgundian, Zocher is the “Brandt & Levie” cold cuts .................10,00 inspiration for our lively meeting place. The Zocher family was known for the • PLATEAU ZOCHER • design of various gardens and parks in Haarlem, the most famous design being HAARLEMSE FROMAGERIE Tasting platter with different the Vondelpark in Amsterdam, and the Frederikspark located next to our hotel. “Bourgondisch Latifstyle” 5 cheeses with cheeses, sausages & “bitterballen” The gardens of Zocher were decorated with many primeval vegetables wich you apple syrup and dried fruit bread .... 13,50 7,50 per person can find in our kitchen! Our chef works closely with local suppliers and uses real and fair robust ingredients. ORGANIC BITTERBALLEN 6 pieces ..................................................... 7,00 BIETERBALLEN • STARTERS • Vegetarian beetroot bitterballen 6 Pieces ..................................................... 7,00 SALADS TASTE OF ZOCHER HOMEMADE PATÉ CLASSIC CAESAR SALAD Combination of Confit of duck, foie gras, MATURED CHEESE STICKS Romaine lettuce, egg, Zocher’s starters ......................... 15,50 p.p onion raisin marmalade 6 Pieces ..................................................... 7,00 Parmesan,homemade Caesar & toasted brioche .................... .......... 13,50 dressing & anchovies ............. 9,50 L 13,50 SHRIMP COCKTAIL OLIVES, BREAD ROLLS, SMOKED TOMATO Grilled chicken ............................... -

ABI/Grupo Modelo Case Study

MERGER ANTITRUST LAW ABI/Grupo Modelo (Full Set of Case Materials) Professor Dale Collins Georgetown University Law Center ABI/GRUPO MODELO Table of Contents AB Inbev/Grupo Modelo (2013) Anheuser-Busch InBev, Press Release, Anheuser-Busch InBev and Grupo Modelo to Combine, Next Step in Long and Successful Partnership (June 29, 2012) ................................................................................................ 4 Constellation Brands, News Release, Constellation Brands Inc. to Acquire Remaining 50 Percent Interest in Crown Imports Joint Venture (June 29, 2012) .............................................................................................. 11 U.S. Dept. of Justice, Antitrust Div., News Release, Justice Department Files Antitrust Lawsuit Challenging Anheuser-Busch Inbev’s Proposed Acquisition of Grupo Modelo (Jan. 31, 2013)............................................... 13 Complaint, United States v. Anheuser-Busch InBev SA/NV, No. 1:13-cv-00127 (D.D.C. filed Jan. 31, 2013) ........................................... 16 Constellation Brands, Inc.’s and Crown Imports LLC’s Motion to Intervene As Defendants (Feb. 7, 2013) ....................................................................... 43 Anheuser-Busch InBev, Press Release, Anheuser-Busch InBev and Constellation Brands Announce Revised Agreement for Complete Divestiture of U.S. Business of Grupo Modelo (Feb. 14, 2013) .................................................. 79 Joint Motion to Stay Proceedings (Feb. 20, 2013) .............................................. -

Sabmiller Plc Anheuser-Busch Inbev SA/NV

THIS DOCUMENT IS IMPORTANT AND REQUIRES YOUR IMMEDIATE ATTENTION. PART II OF THIS DOCUMENT COMPRISES AN EXPLANATORY STATEMENT IN COMPLIANCE WITH SECTION 897 OF THE COMPANIES ACT 2006. THIS DOCUMENT RELATES TO A TRANSACTION WHICH, IF IMPLEMENTED, WILL RESULT IN THE CANCELLATION OF THE LISTINGS OF SABMILLER SHARES ON THE OFFICIAL LIST OF THE LONDON STOCK EXCHANGE AND THE MAIN BOARD OF THE JOHANNESBURG STOCK EXCHANGE, AND OF TRADING OF SABMILLER SHARES ON THE LONDON STOCK EXCHANGE’S MAIN MARKET FOR LISTED SECURITIES AND ON THE MAIN BOARD OF THE JOHANNESBURG STOCK EXCHANGE. THE SECURITIES PROPOSED TO BE ISSUED PURSUANT TO THE UK SCHEME WILL NOT BE REGISTERED WITH THE SEC UNDER THE US SECURITIES ACT OR THE SECURITIES LAWS OF ANY STATE OR OTHER JURISDICTION OF THE UNITED STATES. THE APPROVAL OF THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE IN ENGLAND AND WALES PROVIDES THE BASIS FOR THE SECURITIES TO BE ISSUED WITHOUT REGISTRATION UNDER THE US SECURITIES ACT, IN RELIANCE ON THE EXEMPTION FROM THE REGISTRATION REQUIREMENTS OF THE US SECURITIES ACT PROVIDED BY SECTION 3(a)(10). If you are in any doubt as to the action you should take, you are recommended to seek your own independent advice as soon as possible from your stockbroker, bank, solicitor, accountant, fund manager or other appropriate independent professional adviser who, if you are taking advice in the United Kingdom, is appropriately authorised to provide such advice under the United Kingdom Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (as amended), or from another appropriately authorised independent financial adviser if you are in a territory outside the United Kingdom. -

Bierliste Ausland Biername Brauerei Stadt Land Note Birell Non-Alcoholic (Gebr

Bierliste Ausland Biername Brauerei Stadt Land Note Birell Non-Alcoholic (gebr. in Ägypten) Al Ahram Beverages Co. Giza Ägypten 4,5 Heineken Lager Premium Al Ahram Beverages Co. Giza Ägypten 3,5 Meister Lager Al Ahram Manufacturing and Filling Co. Giza Ägypten 3,5 Sakara Gold Lager Al Ahram Beverages Co. Giza Ägypten 3,6 Stella Export Lager Al Ahram Beverages Co. Giza Ägypten 3,8 Stella Lager Al Ahram Beverages Co. Giza Ägypten 3,3 Stella Lager 115 Years Al Ahram Beverages Co. Giza Ägypten 3,0 Patagonia Estilo Amber Lager Cerveceria Quilmes SAICAY Buenos Aires Argentinien 2,7 Quilmes Cerveza Cerveceria Malteria Quilmes Buenos Aires Argentinien 4,0 Quilmes Cerveza Cristal Cerveceria Malteria Quilmes Buenos Aires Argentinien 3,8 Bati Beer Lager Kombolcha Brewery Kombolcha Äthiopien 3,7 Castlemaine XXXX Gold Lager Castlemaine Perkins Milton Brisbane Australien 3,7 Coopers Sparkling Ale Coopers Brewery LTD. Regency Park Australien 3,3 Foster´s Lager Carlton & United Melbourne Australien 4,0 James Boag's Premium Lager J. Boag & Son Brewing Launceston Australien 3,7 Reschs Pilsener Carlton & United Breweries Sydney Australien 4,3 Victoria Bitter Lager Carlton & United Breweries Southbank Australien 4,0 Banks Caribbean Lager Banks Breweries LTD. Christ Church Barbados 2,7 400 Jaar Brandaris Terschelling door Brouwerij Van Steenberge Ertvelde Belgien 3,8 Abbaye d´Aulne Amber Brasserie Val de Sambre Gozee Belgien 4,4 Abbaye du Val-Dieu Biere de Noel Brasserie de l´Abbaye du Val-Dieu Aubel Belgien 3,3 Adelardus Trudoabdijbier Tripel Brouwerij Kerkom Sint-Truiden Belgien 3,8 Archivist Hell Brouwerij De Brabandere Bavikhove Belgien 3,5 Arend blond Brouwerij De Ryck Herzele Belgien 4,3 Baltimore-Washington Beer Works Route US 66 Brewery Strubbe Ichtegem Belgien 3,0 Barista Chocolate Quad Br. -

United States V. Anheuser-Busch Inbev SA/NV (DDC)--Complaint

Case 1:16-cv-01483 Document 1 Filed 07/20/16 Page 1 of 18 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, U.S. Department of Justice Antitrust Division 450 Fifth Street, NW, Suite 4100 Washington, DC 20530, Plaintiff, v. ANHEUSER-BUSCH InBEV SA/NV Case No. Brouwerijplein, 1 3000 Leuven Belgium, and SABMILLER pk SABMiller House Church Street West Woking, Surry GU216HS United Kingdom, Defendants. COMPLAINT 1. The United States of America brings this civil antitrust action to enjoin Anheuser- Busch InBev SA/NV ("ABI") from acquiring SABMiller pk ("SABMiller"). The United States alleges as follows: Case 1:16-cv-01483 Document 1 Filed 07/20/16 Page 2 of 18 I. NATURE OF THE ACTION 2. On November 11, 2015, ABI agreed to acquire SABMiller in a transaction valued at $107 billion. 3. ABI is the largest brewing company both in the United States and worldwide. In the United States, ABI accounts for approximately 4 7% of all beer sales. 1 4. SABMiller is the second-largest global brewing company. In the United States, SABMiller owns 58% ofMillerCoors LLC ("MillerCoors"), which is a joint venture between SABMiller and Molson Coors Brewing Company ("Molson Coors"). In the United States, MillerCoors is the second-largest brewing company, accounting for 25% of all beer sales, and is ABI's largest competitor. 5. ABI and MillerCoors are the two largest brewers in local beer markets throughout the United States and have combined market shares that range from 37% to 94% of beer sales in 58 Metropolitan Statistical Areas ("MSA") in the United States.2 In more than 15 of these MSAs, ABI and MillerCoors jointly account for 70% or more of beer sales. -

Retail Price List - Dutchess & Ulster Counties May 20, 2014

Dutchess Beer Distributors Retail Price List - Dutchess & Ulster Counties May 20, 2014 Package Frontline Quantity Discount Final Cost Budweiser & Bud Light 40oz. Bottles $28.55 1 Case N/A $28.55 15/22oz. Bottles $19.55 1 Case N/A $19.55 15/25oz. Cans $22.85 5 Cases $2.45 $20.40 4/6/16oz. Cans $27.00 1 Case N/A $27.00 4/6/12oz. Bottles $22.25 1 Case N/A $22.25 4/6/12oz. Cans $22.25 5 Cases $0.90 $21.35 10 Cases $1.40 $20.85 2/12 8oz. Cans $13.70 5 Cases $3.05 $10.65 4/6/7oz. Bottles $16.45 1 Case N/A $16.45 Big Red & Big Blue 24/12 Bottles $19.05 1 Case N/A $19.05 3/8/16oz. Alumin. Twist-off $29.30 1 Case $6.80 $22.50 Budweiser, Bud Light, Bud Select & Select 55 2/12/12oz. Bottles & Cans $19.60 1 Case N/A $19.60 18/12oz. Bottles & Cans $13.65 25 Cases $0.40 $13.25 50 Cases $0.80 $12.85 70 Cases $1.60 $12.05 30/12oz. Cans $20.85 1 Case N/A $20.85 Budweiser, Bud Light & Bud Ice 15/18oz. Bottles $14.41 5 Cases $3.91 $10.50 10 Cases $4.56 $9.85 Budweiser Select & Bud Ice 15/25oz. Cans $22.85 2 Cases $6.05 $16.80 Budweiser & Bud Light Chelada - Picante' 15/25oz. Cans $32.35 2 Cases $4.00 $28.35 Bud Light Lime, Bud Light Platinum & Budweiser Black Crown 4/6/12oz.