The Lady's Slipper Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Willi Orchids

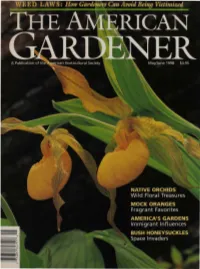

growers of distinctively better plants. Nunured and cared for by hand, each plant is well bred and well fed in our nutrient rich soil- a special blend that makes your garden a healthier, happier, more beautiful place. Look for the Monrovia label at your favorite garden center. For the location nearest you, call toll free l-888-Plant It! From our growing fields to your garden, We care for your plants. ~ MONROVIA~ HORTICULTURAL CRAFTSMEN SINCE 1926 Look for the Monrovia label, call toll free 1-888-Plant It! co n t e n t s Volume 77, Number 3 May/June 1998 DEPARTMENTS Commentary 4 Wild Orchids 28 by Paul Martin Brown Members' Forum 5 A penonal tour ofplaces in N01,th America where Gaura lindheimeri, Victorian illustrators. these native beauties can be seen in the wild. News from AHS 7 Washington, D . C. flower show, book awards. From Boon to Bane 37 by Charles E. Williams Focus 10 Brought over f01' their beautiful flowers and colorful America)s roadside plantings. berries, Eurasian bush honeysuckles have adapted all Offshoots 16 too well to their adopted American homeland. Memories ofgardens past. Mock Oranges 41 Gardeners Information Service 17 by Terry Schwartz Magnolias from seeds, woodies that like wet feet. Classic fragrance and the ongoing development of nell? Mail-Order Explorer 18 cultivars make these old favorites worthy of considera Roslyn)s rhodies and more. tion in today)s gardens. Urban Gardener 20 The Melting Plot: Part II 44 Trial and error in that Toddlin) Town. by Susan Davis Price The influences of African, Asian, and Italian immi Plants and Your Health 24 grants a1'e reflected in the plants and designs found in H eading off headaches with herbs. -

The General Status of Alberta Wild Species 2000 | I Preface

Pub No. I/023 ISBN No. 0-7785-1794-2 (Printed Edition) ISBN No. 0-7785-1821-3 (On-line Edition) For copies of this report, contact: Information Centre – Publications Alberta Environment/Alberta Sustainable Resource Development Main Floor, Great West Life Building 9920 - 108 Street Edmonton, Alberta, Canada T5K 2M4 Telephone: (780) 422-2079 OR Information Service Alberta Environment/Alberta Sustainable Resource Development #100, 3115 - 12 Street NE Calgary, Alberta, Canada T2E 7J2 Telephone: (403) 297-3362 OR Visit our website at www.gov.ab.ca/env/fw/status/index.html (available on-line Fall 2001) Front Cover Photo Credits: OSTRICH FERN - Carroll Perkins | NORTHERN LEOPARD FROG - Wayne Lynch | NORTHERN SAW-WHET OWL - Gordon Court | YELLOW LADY’S-SLIPPER - Wayne Lynch | BRONZE COPPER - Carroll Perkins | AMERICAN BISON - Gordon Court | WESTERN PAINTED TURTLE - Gordon Court | NORTHERN PIKE - Wayne Lynch ASPEN | gordon court prefacepreface Alberta has long enjoyed the legacy of abundant wild species. These same species are important environmental indicators. Their populations reflect the health and diversity of the environment. Alberta Sustainable Resource Development The preparation and distribution of this report is has designated as one of its core business designed to achieve four objectives: goals the promotion of fish and wildlife conservation. The status of wild species is 1. To provide information on, and raise one of the performance measures against awareness of, the current status of wild which the department determines the species in Alberta; effectiveness of its policies and service 2. To stimulate broad public input in more delivery. clearly defining the status of individual Central to achieving this goal is the accurate species; determination of the general status of wild 3. -

Vol 29 #2.Final

$5.00 (Free to Members) Vol. 33, No. 1 January 2005 FREMONTIA A JOURNAL OF THE CALIFORNIA NATIVE PLANT SOCIETY IN THIS ISSUE: THE CALIFORNIA NATIVE PLANT SOCIETY: ITS MISSION, HISTORY, AND HEART by Carol Witham 3 THE CALIFORNIA NATIVE PLANT SOCIETY AT THE STATE LEVEL: WHO WE ARE AND WHAT WE DO by Michael Tomlinson 11 SAVING A RARE PLANT IN AN URBAN ENVIRONMENT by Keith Greer and Holly Cheong 18 POLLINATION BIOLOGY OF THE CLUSTERED LADY SLIPPER by Charles L. Argue 23 GROWING NATIVES: CALIFORNIA BUCKEYE by Glenn Keater 29 DR. MALCOLM MCLEOD, 2004 FELLOW by Dirk R. Walters 30 VOLUME 33:1, JANUARY 2005 FREMONTIA 1 40TH ANNIVERSARY OF CNPS CALIFORNIA NATIVE PLANT SOCIETY FREMONTIA CNPS, 2707 K Street, Suite 1; Sacramento, CA 95816-5113 (916) 447-CNPS (2677) Fax: (916) 447-2727 VOL. 33, NO. 1, JANUARY 2005 [email protected] Copyright © 2005 MEMBERSHIP California Native Plant Society Membership form located on inside back cover; dues include subscriptions to Fremontia and the Bulletin Linda Ann Vorobik, Editor Mariposa Lily . $1,000 Supporting . $75 Bob Hass, Copy Editor Benefactor . $500 Family, Group, International . $45 Beth Hansen-Winter, Designer Patron . $250 Individual or Library . $35 Justin Holl, Jake Sigg & David Tibor, Plant Lover . $100 Student/Retired/Limited Income . $20 Proofreaders STAFF CHAPTER COUNCIL CALIFORNIA NATIVE CALIFORNIA NATIVE Sacramento Office: Alta Peak (Tulare) . Joan Stewart PLANT SOCIETY Executive Director . Pamela C. Bristlecone (Inyo-Mono) . Sherryl Taylor Muick, PhD Channel Islands . Lynne Kada Dedicated to the Preservation of Development Director . vacant Dorothy King Young (Mendocino/ the California Native Flora Membership Assistant . -

Slippers of the Spirit

SLIPPERS OF THE SPIRIT The Genus Cypripedium in Manitoba ( Part 1 of 2 ) by Lorne Heshka he orchids of the genus Cypripedium, commonly known as Lady’s-slippers, are represented by some Tforty-five species in the north temperate regions of the world. Six of these occur in Manitoba. The name of our province is aboriginal in origin, borrowed Cypripedium from the Cree words Manitou (Great Spirit) and wapow acaule – Pink (narrows) or, in Ojibwe, Manitou-bau or baw. The narrows Lady’s-slipper, or referred to are the narrows of Lake Manitoba where strong Moccasin-flower, winds cause waves to crash onto the limestone shingles of in Nopiming Manitou Island. The First Nations people believed that this Provincial Park. sound was the voice or drumbeat of the Manitou. A look at the geological map of Manitoba reveals that the limestone bedrock exposures of Manitou Island have been laid down by ancient seas and underlies all of southwest Manitoba. As a result, the substrates throughout this region Lorne Heshka are primarily calcareous in nature. The Precambrian or Canadian Shield occupies the portion of Manitoba east of N HIS SSUE Lake Winnipeg and north of the two major lakes, to I T I ... Nunavut. Granitic or gneissic in nature, these ancient rocks create acidic substrates. In the north, the Canadian Shield Slippers of the Spirit .............................p. 1 & 10-11 adjacent to Hudson Bay forms a depression that is filled Loving Parks in Tough Economic Times ................p. 2 with dolomite and limestone strata of ancient marine Member Profile: June Thomson ..........................p. 3 origins. -

Response of Cypripedium and Goodyera to Disturbance in the Thunder Bay Area

Lakehead University Knowledge Commons,http://knowledgecommons.lakeheadu.ca Electronic Theses and Dissertations Undergraduate theses 2018 Response of Cypripedium and Goodyera to disturbance in the Thunder Bay area Davis, Danielle http://knowledgecommons.lakeheadu.ca/handle/2453/4426 Downloaded from Lakehead University, KnowledgeCommons 5(63216(2)&<35,3(',80$1'*22'<(5$72',6785%$1&(,1 7+(7+81'(5%$<$5($ E\ 'DQLHOOH'DYLV )$&8/7<2)1$785$/5(6285&(60$1$*(0(17 /$.(+($'81,9(56,7< 7+81'(5%$<217$5,2 0D\ RESPONSE OF CYPRIPEDIUM AND GOODYERA TO DISTURBANCE IN THE THUNDER BAY AREA by Danielle Davis An Undergraduate Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Honours Bachelor of Environmental Management Faculty of Natural Resources Management Lakehead University May 2018 Major Advisor Second Reader ii LIBRARY RIGHTS STATEMENT In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the HBEM degree at Lakehead University in Thunder Bay, I agree that the University will make it freely available for inspection. This thesis is made available by my authority solely for the purpose of private study and research and may not be copied or reproduced in whole or in part (except as permitted by the Copyright Laws) without my written authority. Signature: Date: iii A CAUTION TO THE READER This HBEM thesis has been through a semi-formal process of review and comment by at least two faculty members. It is made available for loan by the Faculty of Natural Resources Management for the purpose of advancing the practice of professional and scientific forestry. -

Diversity and Evolution of Monocots

Lilioids - petaloid monocots 4 main groups: Diversity and Evolution • Acorales - sister to all monocots • Alismatids of Monocots – inc. Aroids - jack in the pulpit ! • Lilioids (lilies, orchids, yams) – grade, non-monophyletic – petaloid . orchids and palms . ! • Commelinoids – Arecales – palms – Commelinales – spiderwort – Zingiberales –banana – Poales – pineapple – grasses & sedges Lilioids - petaloid monocots Asparagales: *Orchidaceae - orchids • finish the Asparagales by 1. Terrestrial/epiphytes: plants looking at the largest family - typically not aquatic the orchids 2. Geophytes: herbaceous above ground with below ground modified perennial stems: bulbs, corms, rhizomes, tubers 3. Tepals: showy perianth in 2 series of 3 each; usually all petaloid, or outer series not green and sepal-like & with no bracts 1 *Orchidaceae - orchids *Orchidaceae - orchids The family is diverse with about 880 genera and over 22,000 All orchids have a protocorm - a feature restricted to the species, mainly of the tropics family. Orchids are • structure formed after germination and before the mycotrophic (= fungi development of the seedling plant dependent) lilioids; • has no radicle but instead mycotrophic tissue some are obligate mycotrophs Cypripedium acaule Corallorhiza striata Stemless lady-slipper Striped coral root Dactylorhiza majalis protocorm *Orchidaceae - orchids *Orchidaceae - orchids Cosmopolitan, but the majority of species are found in the Survive in these epiphytic and other harsh environments via tropics and subtropics, ranging from sea -

Pink Lady-Slipper, with a Distinctive Inflated Slipper- Like Lip Petal, Veined with Red and with a Crease Down the Front

Wildflower Spot – May 2011 John Clayton Chapter of the Virginia Native Plant Society Cypripedium acaule President of the John Clayton Chapter, PinkVNPS Lady-Slipper By Helen Hamilton, No flower is more recognizable than the pink lady-slipper, with a distinctive inflated slipper- like lip petal, veined with red and with a crease down the front. This is our only lady-slipper without stem leaves. Surrounding the base of the flower-stem is a subopposite pair of wide, ribbed, and oval 8-inch leaves. These perennial orchids are found in acid soil, from swamps and bogs to dry woods and sand- dunes. They do poorly in deep shade and are usually found in old forests with broken canopy or in young forests regenerating after logging or fire. Road cuts and other edge habitats are also good places to find them. Lady-slippers are native to every county in regarded as aphrodisiacs. The “doctrine of Virginia, growing along the mountains and signatures” refers to an ancient idea that if coastal plain to South Carolina and Alabama, a plant part was shaped like a human organ and in most areas of eastern and central U.S. or suggested a disease, then that plant was and Canada. useful for that particular organ or ailment. A plant widely used in the 1800’s as a sedative, This species is very difficult to grow under the hairy stems have caused dermatitis. Both garden conditions, and must have certain the pink and yellow lady-slipper wereMedicinal often microscopic fungi which the tiny seeds require Plantsharvested and inHerbs the 19th century, contributing to for development. -

Plant Species of Maryland's Piedmont That Are Regionally Rare but Not State Rare Cris Fleming - January 2010

PLANT SPECIES OF MARYLAND'S PIEDMONT THAT ARE REGIONALLY RARE BUT NOT STATE RARE CRIS FLEMING - JANUARY 2010 This is a list of plant species not on Maryland's list of Rare, Threatened & Endangered Species but considered by me to be regionally rare or uncommon in Maryland's Piedmont Region (Montgomery, Carroll, Howard, Baltimore, & Harford Co) and the inner Coastal Plain areas near Washington (Prince Georges, Charles, & Anne Arundel Co). Although other botanists have been consulted, this list is mostly based on my own field experience and is not considered complete or authoritative. With a few exceptions, all plant species listed here have been seen by me in one or more of these counties. This list is for the use of members of MNPS doing field surveys in the Piedmont Region. It was prepared as one of the goals of the botany committee for the year 2002 and was completed in January 2003 and revised in February 2007 and again in January 2010. Nomenclature follows Gleason and Cronquist, Manual of Vascular Plants of Northeastern United States and Adjacent Canada, Second Edition, 1991. The great majority of plants listed here as regionally rare are northern species that do grow in Maryland in the mountain counties because the climate is cooler there. The long, warm summers of the Piedmont counties preclude the widespread occurrence of many northern species. However, species of these cooler regions sometimes do occur in the Piedmont region on north-facing slopes, in shady ravines, or in especially rich, moist soil. Other species are regionally rare because their habitat is regionally rare, for instance shale barrens, serpentine barrens, diabase openings, and cool seepage swamps. -

GEOGRAPHIC and SOIL NUTRIENT LINKS in the MYCORRHIZAL ASSOCIATION of a RARE ORCHID, CYPRIPEDIUM ACAULE by WILLIAM DOUGLAS BUNCH

GEOGRAPHIC AND SOIL NUTRIENT LINKS IN THE MYCORRHIZAL ASSOCIATION OF A RARE ORCHID, CYPRIPEDIUM ACAULE by WILLIAM DOUGLAS BUNCH (Under the Direction of Richard P. Shefferson) ABSTRACT Mycorrhizal associations are a requirement for the germination of orchids in nature. Recent studies have shown that the distributions of ectomycorrhizal and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi are highly correlated with soil nutrient availability. However, it is unclear how soil nutrient availability influences fungal association in the orchid mycorrhiza. This study was conducted with the goal of determining patterns in orchid mycorrhizal host specialization associated with soil nutrient conditions. Seventeen Cypripedium acaule populations were sampled across central and northern Georgia. Soil samples were collected at the site of each plant and analyzed for carbon, total nitrogen, ammonium, nitrate, and pH. Mycorrhizal fungal hosts of each plant were identified from root samples using DNA analysis of key fungal barcoding genes. C. acaule was found associating with a wide range of fungi, but was most commonly found associating with Tulasnella and Russula species. We observed a strong association between geography, soil nutrient availability and the fungi colonizing C. acaule. INDEX WORDS: Mycorrhiza; Orchid; Soil nutrients; Geographic mosaic GEOGRAPHIC AND SOIL NUTRIENT LINKS IN THE MYCORRHIZAL ASSOCIATION OF A RARE ORCHID, CYPRIPEDIUM ACAULE by WILLIAM DOUGLAS BUNCH B.S., University of Georgia, 2010 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF SCIENCE ATHENS, GEORGIA 2012 © 2012 William Douglas Bunch All Rights Reserved GEOGRAPHIC AND SOIL NUTRIENT LINKS IN THE MYCORRHIZAL ASSOCIATION OF A RARE ORCHID, CYPRIPEDIUM ACAULE by WILLIAM DOUGLAS BUNCH Major Professor: Richard P. -

Wildflowers and Ferns Along the Acton Arboretum Wildflower Trail and in Other Gardens FERNS (Including Those Occurring Naturally

Wildflowers and Ferns Along the Acton Arboretum Wildflower Trail and In Other Gardens Updated to June 9, 2018 by Bruce Carley FERNS (including those occurring naturally along the trail and both boardwalks) Royal fern (Osmunda regalis): occasional along south boardwalk, at edge of hosta garden, and elsewhere at Arboretum Cinnamon fern (Osmunda cinnamomea): naturally occurring in quantity along south boardwalk Interrupted fern (Osmunda claytoniana): naturally occurring in quantity along south boardwalk Maidenhair fern (Adiantum pedatum): several healthy clumps along boardwalk and trail, a few in other Arboretum gardens Common polypody (Polypodium virginianum): 1 small clump near north boardwalk Hayscented fern (Dennstaedtia punctilobula): aggressive species; naturally occurring along north boardwalk Bracken fern (Pteridium aquilinum): occasional along wildflower trail; common elsewhere at Arboretum Broad beech fern (Phegopteris hexagonoptera): up to a few near north boardwalk; also in rhododendron and hosta gardens New York fern (Thelypteris noveboracensis): naturally occurring and abundant along wildflower trail * Ostrich fern (Matteuccia pensylvanica): well-established along many parts of wildflower trail; fiddleheads edible Sensitive fern (Onoclea sensibilis): naturally occurring and abundant along south boardwalk Lady fern (Athyrium filix-foemina): moderately present along wildflower trail and south boardwalk Common woodfern (Dryopteris spinulosa): 1 patch of 4 plants along south boardwalk; occasional elsewhere at Arboretum Marginal -

Publications1

PUBLICATIONS1 Book Chapters: Zettler LW, J Sharma, and FN Rasmussen. 2003. Mycorrhizal Diversity (Chapter 11; pp. 205-226). In Orchid Conservation. KW Dixon, SP Kell, RL Barrett and PJ Cribb (eds). 418 pages. Natural History Publications, Kota Kinabalu, Sabah, Malaysia. ISBN: 9838120782 Books and Book Chapters Edited: Sharma J. (Editor). 2010. North American Native Orchid Conservation: Preservation, Propagation, and Restoration. Conference Proceedings of the Native Orchid Conference - Green Bay, Wisconsin. Native Orchid Conference, Inc., Greensboro, North Carolina. 131 pages, plus CD. (Public Review by Dr. Paul M. Catling published in The Canadian Field-Naturalist Vol. 125. pp 86 - 88; http://journals.sfu.ca/cfn/index.php/cfn/article/viewFile/1142/1146). Peer-reviewed Publications (besides Journal publications or refereed proceedings) Goedeke, T., Sharma, J., Treher, A., Frances, A. & *Poff, K. 2016. Calopogon multiflorus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T64175911A86066804. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016- 1.RLTS.T64175911A86066804.en. Treher, A., Sharma, J., Frances, A. & *Poff, K. 2015. Basiphyllaea corallicola. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2015: e.T64175902A64175905. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2015- 4.RLTS.T64175902A64175905.en. Goedeke, T., Sharma, J., Treher, A., Frances, A. & *Poff, K. 2015. Corallorhiza bentleyi. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2015: e.T64175940A64175949. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2015- 4.RLTS.T64175940A64175949.en. Treher, A., Sharma, J., Frances, A. & *Poff, K. 2015. Eulophia ecristata. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2015: e.T64176842A64176871. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2015- 4.RLTS.T64176842A64176871.en. -

Cypripedium Montanum Douglas Ex Lindley (Mountain Lady's Slipper): a Technical Conservation Assessment

Cypripedium montanum Douglas ex Lindley (mountain lady’s slipper): A Technical Conservation Assessment Prepared for the USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region, Species Conservation Project February 21, 2007 Nan C. Vance, Ph.D. Pacific Northwest Research Station 3200 SW Jefferson Way Corvallis, OR 97331 Peer Review Administered by Center for Plant Conservation Vance, N.C. (2007, February 21). Cypripedium montanum Douglas ex Lindley (mountain lady’s slipper): a technical conservation assessment. [Online]. USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region. Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/r2/projects/scp/assessments/cypripediummontanum.pdf [date of access]. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This project was funded in part by USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region, and Pacific Northwest Research Station, and by Kelsey Creek Laboratories, Issaquah, WA. Many thanks to Greg Karow, Forester, Bighorn National Forest who provided the essential and necessary site and population data for this assessment and Tucker Galloway whose dedicated field work provided important new information. Another important source of information is the Wyoming Natural Diversity Database, and I appreciate the excellent cooperation of Bonnie Heidel, Botanist, and Tessa Ducher, Database Specialist. I would also like to express my gratitude to Cathy Seibert, collections manager at the Montana State Herbarium, Peter Bernhardt, Professor of Botany at Saint Louis University, Dan Luoma and Joyce Eberhart, mycologists at Oregon State University, Roger and Jane Smith of Kelsey Creek Laboratories, and Julie Knorr, Botanist on the Klamath National Forest, for their help and information. I am grateful to David Anderson for his advice and for generously allowing me to use an assessment he authored as a model and guide.