The Fastest Humans on Earth: Environmental Surroundings and Family Influences That Spark Talent Development in Olympic Speed Skaters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

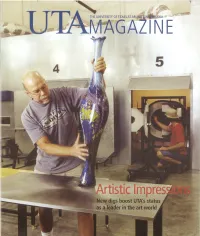

New Digs Boost UTA's Status As a Leader in the Art World

THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT ARLING2 A NE 4 New digs boost UTA's status as a leader in the art world EDITOR Mark Permenter UTA.VOL. XXVII • NO. 1 • FALL 2004 ASSISTANT EDITOR/ SENIOR WRITER Jim Patterson CONTRIBUTING WRITERS Donna Darovich Laura Hanna Beverlee Matthys IN THIS ISSUE Sherry W Neaves Bill Petitt Sue Stevens 10 Danny Woodward Handicapping the race for the White House Will George W Bush be re-elected in November or will John Kerry become the 44th president COPY EDITOR John Dycus of the United States? A UTA political science professor analyzes the race using nine factors. by Thomas R. Marshall CREATIVE DIRECTOR Joel Quintans DESIGNER 12 Artistic impressions Carol A. Lehman The Studio Arts Center, a state-of-the-art facility that opened this fall, is attracting students CONTRIBUTING DESIGNER from near and far and helping make UTA a preferred destination for those serious about art. Melissa Renken by Sherry Wodraska Neaves PHOTOGRAPHER Robert Crosby CONTRIBUTING PHOTOGRAPHERS 18 The best thing on wheels Charlotte Hartzell Catrice Tkadlec Paralyzed at age 16 when a half-ton hay bale crushed him, Randy Snow became one of the world's premier wheelchair athletes—and the first inducted into the Olympic Hall of Fame. COVER Joel Quintans by Danny Woodward Robert Crosby Charlotte Hartzell WEB DESIGN Chuck Pratt Andrew Leverenz Cornelius Smith PRINTING UTA Campus Printing ON THE COVER Art Associate Professor David Keens has built one of the most respected glass programs in the country. LENSCAPE Staff photographer Robert Crosby used a DECISION 105-millimeter lens to capture fall foliage in the architecture courtyard. -

Announcement Release 2013

THE HENRY R. KRAVIS PRIZE IN LEADERSHIP FOR 2013 AWARDED TO JOHANN OLAV KOSS FOUR-TIME OLYMPIC GOLD MEDALIST-TURNED- NONPROFIT LEADER Olympic speed skater from Norway founded Right To Play, an organization that uses the transformative power of play to educate and empower children facing adversity. Claremont, Calif., March 6, 2013–– Claremont McKenna College (CMC) announced today that four-time Olympic gold medalist and nonprofit leader Johann Olav Koss has been awarded the eighth annual Henry R. Kravis Prize in Leadership. The Kravis Prize, which carries a $250,000 award designated to the recipient organization, recognizes extraordinary leadership in the nonprofit sector. Koss will be presented with The Kravis Prize at a ceremony on April 18 held on the CMC campus. Founded in 2000 by Koss, Right To Play is a global organization that uses the transformative power of play to educate and empower children facing adversity. Right To Play’s impact is focused on four areas: education, health, peace building, and community development. Right To Play reaches 1 million children in more than 20 countries through play programming that teaches them the skills to build better futures, while driving social change in their communities. The organization promotes the involvement of all children and youth by engaging with girls, persons with disabilities, children affected by HIV/AIDS, as well as former combatants and refugees. “We use play as a way to teach and empower children,” Koss says. “Play can help children overcome adversity and understand there are people who believe in them. We would like every child to understand and accept their own abilities, and to have hopes and dreams. -

Finishlynx Sports Timing Systems

FinishLynx Timing & Results Systems Lynx System Developers Lynx System FinishLynx Sports Timing & Event Management Solutions July 2017 INTERNATIONAL SPORTS TIMING PACKAGES CONTENTS Description Page Regulatory Acceptance and Reference Letters 4 Athletics – Photo-Finish and Timing for Track Events 6 Athletics - False Start Detection 8 Athletics - Field Events 9 Canoe - Kayak - Rowing – Photo-Finish and Timing 10 Cycling – Photo-Finish and Timing 12 Speed Skating – Photo-Finish and Timing 14 High Velocity Sports – Photo-Finish and Timing 16 Pari-Mutuel Sports – Photo-Finish and Timing 16 Reference Venues & Events 20 www.finishlynx.com PAGE 2 INTERNATIONAL SPORTS TIMING PACKAGES 3 KEY REASONS TO CHOOSE LYNX SIMPLE AND POWERFUL FinishLynx technology incorporates two decades of industry and customer feedback, 1 which yields products that are powerful, customizable, and easy to use. Underlying all Lynx products is a philosophy that all our products should link together seamlessly. This idea of links between products is the motivation for the company name: Lynx. This seamless product integration ensures that producing accurate results is easy. From start lists, to results capture, to information display―data flows instantly and automatically with FinishLynx. MODULAR AND EXPANDABLE The entire Lynx product line is designed so the customer can easily expand in two ways: by 2 adding new products or by upgrading existing ones. Customers can feel confident knowing that if they choose an entry-level system, they can always upgrade to a higher level at a later date. Our commitment to ongoing development means that enhancements are constantly added to our hardware, software, and third-party integration. And thanks to our commitment to free software updates, you can always download the latest software releases right from our website. -

Media-Images-And-Words-In-Womens

Our mission is to advance the lives of girls and women through sport and physical activity. THE FOUNDATION POSITION MEDIA – IMAGES AND WORDS IN WOMEN’S SPORTS In 1994, the Women’s Sports Foundation issued “Words to Watch,” guidelines for treating male and female athletes equally in sports reporting and commentary. This publication was developed in response to a number of events in which media were criticized for sexist comments made during network broadcasts or in newspaper and magazine coverage of women’s sports. The guidelines were distributed to electronic and print media on the Foundation’s media list and by request. “Words to Watch” was adapted with permission of the Canadian Association for the Advancement of Women in Sports, 1994. Section II of this publication remains as “Words to Watch.” In response to numerous questions and criticisms of the visual and narrative portrayal of female athletes on television and female athlete imagery appearing in print media, the Foundation has expanded its “Words to Watch” publication to incorporate imagery and to raise pertinent issues related to authentic and realistic reporting about and depiction of girls and women in sports and fitness. “Images to Watch” was added to this publication in October of 1995 and the main title revised accordingly (see Section I of this publication). This publication also includes a new section written specifically for female athletes who are asked to participate in electronic and print media advertising or other projects. This section (see Section III) was designed to educate athletes about their rights as models and to provide ethics guidelines for decision-making related to their participation in advertising and other visual and written programming regarding how they are portrayed. -

Girls' Sports Reading List

Girls’ Sports Reading List The books on this list feature girls and women as active participants in sports and physical activity. There are books for all ages and reading levels. Some books feature champion female athletes and others are fiction. Most of the books written in the 1990's and 2000’s are still in print and are available in bookstores. Earlier books may be found in your school or public library. If you cannot find a book, ask your librarian or bookstore owner to order it. * The descriptions for these books are quoted with permission from Great Books for Girls: More than 600 Books to Inspire Today’s Girls and Tomorrow’s Women, Kathleen Odean, Ballantine Books, New York, 1997. ~ The descriptions for these books are quoted from Amazon.com. A Turn for Lucas, Gloria Averbuch, illustrations by Yaacov Guterman, Mitten Press, Canada, 2006. Averbuch, author of best-selling soccer books with legends like Brandi Chastain and Anson Dorrance, shares her love of the game with children in this book. This is a story about Lucas and Amelia, the soccer-playing twins who share this love of the game. A Very Young Skater, Jill Krementz, Dell Publishing, New York, NY, 1979. Ages 7-10, 52 p., ($6.95). The story of a 10-year-old female skater told in words and pictures. A Winning Edge, Bonnie Blair with Greg Brown, Taylor Publishing, Dallas, TX, 1996. Ages 8- 12, 38 p., ($14.95). Bonnie Blair shares her passion and motivation for skating, the obstacles that she’s faced, the sacrifices and the victories. -

International Olympic Committee, Lausanne, Switzerland

A PROJECT OF THE INTERNATIONAL OLYMPIC COMMITTEE, LAUSANNE, SWITZERLAND. WWW.OLYMPIC.ORG TEACHING VALUESVALUES AN OLYYMPICMPIC EDUCATIONEDUCATION TOOLKITTOOLKIT WWW.OLYMPIC.ORG D R O W E R O F D N A S T N E T N O C TEACHING VALUES AN OLYMPIC EDUCATION TOOLKIT A PROJECT OF THE INTERNATIONAL OLYMPIC COMMITTEE, LAUSANNE, SWITZERLAND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The International Olympic Committee wishes to thank the following individuals for their contributions to the preparation of this toolkit: Author/Editor: Deanna L. BINDER (PhD), University of Alberta, Canada Helen BROWNLEE, IOC Commission for Culture & Olympic Education, Australia Anne CHEVALLEY, International Olympic Committee, Switzerland Charmaine CROOKS, Olympian, Canada Clement O. FASAN, University of Lagos, Nigeria Yangsheng GUO (PhD), Nagoya University of Commerce and Business, Japan Sheila HALL, Emily Carr Institute of Art, Design & Media, Canada Edward KENSINGTON, International Olympic Committee, Switzerland Ioanna MASTORA, Foundation of Olympic and Sport Education, Greece Miquel de MORAGAS, Centre d’Estudis Olympics (CEO) Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (UAB), Spain Roland NAUL, Willibald Gebhardt Institute & University of Duisburg-Essen, Germany Khanh NGUYEN, IOC Photo Archives, Switzerland Jan PATERSON, British Olympic Foundation, United Kingdom Tommy SITHOLE, International Olympic Committee, Switzerland Margaret TALBOT, United Kingdom Association of Physical Education, United Kingdom IOC Commission for Culture & Olympic Education For Permission to use previously published or copyrighted -

A Leader's Guide To

A Leader’s Guide to couNT on me Brad Herzog A Leader’s Guide to Count on Me: Sports by Brad Herzog, copyright © 2014. Free Spirit Publishing Inc., Minneapolis, MN; 1-800-735-7323; www.freespirit.com. All rights reserved. A Leader’s Guide to Count on Me: Sports by Brad Herzog, copyright © 2014. Free Spirit Publishing Inc., Minneapolis, MN; 1-800-735-7323; www.freespirit.com. All rights reserved. CONTENTS A NOTE TO TEACHERS, COACHES, YOUTH LEADERS, PARENTS, AND OTHER ADULTS ...............4 INSPIRING STORIES OF SPORTSMANSHIP .................................................................................5 Questions for Reflection, Discussion, and Writing POWERFUL STORIES OF PERSEVERANCE IN SPORTS .................................................................8 Questions for Reflection, Discussion, and Writing REMARKABLE STORIES OF TEAMWORK IN SPORTS ................................................................. 11 Questions for Reflection, Discussion, and Writing AWESOME STORIES OF GENEROSITY IN SPORTS ..................................................................... 14 Questions for Reflection, Discussion, and Writing INCREDIBLE STORIES OF COURAGE IN SPORTS ........................................................................17 Questions for Reflection, Discussion, and Writing ABOUT THE AUTHOR....................................................................................................................21 A Note to Teachers, Coaches, Youth Leaders, Parents, and Other Adults The Count on Me: Sports series is a collection -

The Olympic 500M Speed Skating

448 Statistica Neerlandica (2010) Vol. 64, nr. 4, pp. 448–459 doi:10.1111/j.1467-9574.2010.00457.x The Olympic 500-m speed skating; the inner–outer lane difference Richard Kamst Department of Operations, University of Groningen, PO Box 800, 9700 AV Groningen, The Netherlands Gerard H. Kuper Department of Economics, Econometrics and Finance, University of Groningen, PO Box 800, 9700 AV Groningen, The Netherlands Gerard Sierksma* Department of Operations, University of Groningen, PO Box 800, 9700 AV Groningen, The Netherlands In 1998, the International Skating Union and the International Olympic Committee decided to skate the 500-m twice during World Single Distances Championships, Olympic Games, and World Cups. The decision was based on a study by the Norwegian statistician N. L. Hjort, who showed that in the period 1984–1994, there was a signifi- cant difference between 500-m times skated with a start in the inner and outer lanes. Since the introduction of the clap skate in the season 1997–1998, however, there has been a general feeling that this differ- ence is no longer significant. In this article we show that this is, in fact, the case. Keywords and Phrases: sports, clap skate, statistics. 1 Inner–outer lane problem A 500-m speed skating race is performed by pairs of skaters. A draw decides whether a skater starts in either the inner or the outer lane of the 400-m rink; see Figure 1. After the first curve, skaters change lanes at the ‘crossing line’. The second curve is the major cause of the difference in time between inner and outer starts. -

Dachkonstruktion Speedskating Oval for the 2010 Winter Olympics in V

14. Internationales Holzbau-Forum 08 Speedskating Oval for the 2010 Winter Olympics in Vancouver, Canada | P. Fast 1 Eisschnelllaufhalle der 2010 Winter Olympics, Vancou- ver - Dachkonstruktion Speedskating Oval for the 2010 Winter Olympics in Vancouver, Canada Stadio per pattinaggio di velocità 2010, giochi olimpici invernali Vancouver - Kanada Halle du patinage de vitesse des Jeux olympiques d’hiver 2010 Vancouver – Canada Paul Fast P. Eng., Struct.Eng., P.E. LEED® AP Fast + Epp structural engineers Vancouver, Canada 14. Internationales Holzbau-Forum 08 2 Speedskating Oval for the 2010 Winter Olympics in Vancouver, Canada | P. Fast 14. Internationales Holzbau-Forum 08 Speedskating Oval for the 2010 Winter Olympics in Vancouver, Canada | P. Fast 3 Speedskating Oval for the 2010 Winter Olympics in Vancouver, Canada 1. Introduction When the IOC awarded the 2010 Winter Olympics to Vancouver,B.C., architectural at- tention immediately turned to the building that would host the long track speed skating venue. Speed skating ovals are unique buildings that provide opportunity for striking ar- chitectural- structural expression. Operating on a lean budget, VANOC (Vancouver Olympic Organizing Committee) decided to offload financial risk for the facility by committing the fixed sum of $60M CAD to the neighbouring City of Richmond, who would then assume ownership of the building and responsibility for the remainder of the $178M construction budget. Following an interna- tional request for proposals, Cannon Design Architects was appointed the prime consult- ant with Fast + Epp structural engineers the structural sub-consultant for the roof struc- ture. Figure 1: Richmond Speed Skating Oval, Richmond, British Columbia, Canada 2. Building Description The speed skating oval is a roughly 100m wide by 200m long building with a total roof area including overhangs of 23,700 square metres. -

19-03 Carlson Center Ice Rink Replacement

FNSB CAPITAL IMPROVEMENT PROGRAM 2019 Project Nomination Form Nominations will be accepted from August 12 to October 11. Please fill out the nomination form as completely as possible. If a section does not apply to the project you are nominating, please leave that section blank. Please attach add itional relevant information to this nomination packet as appropriate. There is no limit to the number of projects that can be submitted. Completed nomination forms can be submitted: In person at: By mail to: Fairbanks North Star Borough Fairbanks North Star Borough Attn: Mayor's Office Attn: Capital Improvement Program 907 Terminal Street PO Box 71267 Fa irbanks, AK 99701 Fairbanks, AK 99707 NOMINATOR'S NAME: j t:.. v r T ~8 ~Et,_,=-v $" ORGANIZATION (IF APPLI CABLE) : _____________________ AFFECTED DEPARTMENT: _ ___.~_ A_,,,e._ t,_~-"--"/1/___ ?_ ~_.;v,_ '/_/;:_; _,C,______ _ ___ _ PHONE : I 'jtJ 7 ) JY7 ... 9111 Project Scope/Description: ~6e' -:- A,.,. e -z./ C/7 / /o/ _,,. ,,., ,;-,..,,r ~r:, ,,. e I J- fu:,rr ~ ,,, ///'-</Pf f {~z-y) 77? -- ? 'I z 3 - "f'P~ {_ p Io ) f/~ ~ - ~ tJ 9 I - C ca. _j/4) ,'//,/,t-;M ,7 ei /'t,~ - q //I{ c/'I 'CA- " ~ .,_.,_ Learn mare at: www.fnsb.us/CIP Page 1 of 11 FNSB CAPITAL IMPROVEMENT PROGRAM SAFETY AND CODE COMPLIANCE 1. Does the project reduce or eliminate a health or safety risk? □ Yes D No Please explain: /1?~-,,,.,...u-ee?? ~/?"~ (!)/ 4'v' C ""? /-/ " --v ;5 If N ~ A/V "!? tt,v>-c!Y"'7 4~/&'V ~ ~ 1·" '7A./ q J7. -

Heerim a Rchitects & Planners

Heerim Architects & Planners & Planners Heerim Architects Your Global Design Partner Selected Projects Heerim Architects & Planners Co., Ltd. Seoul, Korea Baku, Azerbaijan Beijing, China Doha, Qatar Dhaka, Bangladesh Dubai, UAE Erbil, Iraq Hanoi, Vietnam Ho Chi Minh, Vietnam New York, USA Nur-Sultan, Kazakhstan Phnom Penh, Cambodia Tashkent, Uzbekistan www.heerim.com 1911 We Design Tomorrow & Beyond 1 CEO Message Heerim, always in the pursuit of a client’s interest and satisfaction Founded in 1970, Heerim Architects & Planners is the leading architectural practice of Korea successfully expanding its mark in both domestic and international markets. Combined with creative thinking, innovative technical knowledge and talented pool of professionals across all disciplines, Heerim provides global standard design solutions in every aspect of the project. Our services strive to exceed beyond the client expectations which extend from architecture, construction management to one-stop Design & Build Management Services delivering a full solution package. Under the vision of becoming the leading Corporate Profile History global design provider, Heerim continues to challenge our goals firmly rooted in our corporate philosophy that “growth Name Heerim Architects & Planners Co., Ltd. 1970 Founded as Heerim Architects & Planners of the company is meaningful when it contributes to a happy, Address 39, Sangil-ro 6-gil, Gangdong-gu, Seoul 05288, Korea 1996 Established In-house Research Institute CEO Jeong, Young Kyoon 1997 Acquired ISO 9001 Certification fulfilled life for all”. Combined with dedicated and innovative 2000 Listed in KOSDAQ CEO / Chair of the Board Jeong, Young Kyoon President Lee, Mog Woon design minds, Heerim continues to expand, diversify, and Licensed and Registered for International Construction Business AIA, KIRA Heo, Cheol Ho 2004 Acquired ISO 14001 Certification explore worldwide where inspiring opportunities allure us. -

The Media Dichotomy of Sport Heros and Sport

THE MEDIA DICHOTOMY OF SPORT important to the consumer: source relevance, HEROS AND SPORT CELEBRITIES: authenticity, and trustworthiness. Chalip (1997) MARKETING OF PROFESSIONAL contends that it is possible to be an unknown hero, WOMEN’S TENNIS PLAYERS but not an unknown celebrity. The primary focus of Chalip’s work is that heroism depends on celebrity, although one need not be a hero to Joshua A. Shuart, Ph.D. become a celebrity. This notion refers to the idea Assistant Professor, Management that the media creates celebrities, that these Sacred Heart University celebrities are fleeting, and that they aren’t real heroes to most people. Finally, Brooks (1998) provided a strong overview of theory and issues The modern sports hero is actually a misnomer for the related to celebrity endorsement involving athletes. sports celebrity. Critics have noted true sports heroes Brooks asked what type of celebrity athlete is most are an endangered species, whereas sports celebrities effective, under what conditions, and most are as common as Texas cockroaches. On the surface importantly, do athletes sell products? Brooks also professional sports seem to offer a natural source for stated that the answer to the question “does a heroes, but on closer examination they offer celebrated (sport) hero have more cultural meaning than a sports figures shaped, fashioned, and marketed as (sport) celebrity?” would have tremendous impact heroic. for marketers. Given the fact that our heroes -SUSAN DRUCKER change as quickly as does the programming on television (Leonard, 1980), it was crucial to reassess the true value of sport heroes and celebrities, and Introduction the tremendous impact that the media plays in There is perhaps no better example of media- creating them in our country.