Analyses of Compact Trichinella Kinomes Reveal a MOS-Like Protein Kinase with a Unique N-Terminal Domain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gastrointestinal Helminthic Parasites of Habituated Wild Chimpanzees

Aus dem Institut für Parasitologie und Tropenveterinärmedizin des Fachbereichs Veterinärmedizin der Freien Universität Berlin Gastrointestinal helminthic parasites of habituated wild chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes verus) in the Taï NP, Côte d’Ivoire − including characterization of cultured helminth developmental stages using genetic markers Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung des Grades eines Doktors der Veterinärmedizin an der Freien Universität Berlin vorgelegt von Sonja Metzger Tierärztin aus München Berlin 2014 Journal-Nr.: 3727 Gedruckt mit Genehmigung des Fachbereichs Veterinärmedizin der Freien Universität Berlin Dekan: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Jürgen Zentek Erster Gutachter: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Georg von Samson-Himmelstjerna Zweiter Gutachter: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Heribert Hofer Dritter Gutachter: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Achim Gruber Deskriptoren (nach CAB-Thesaurus): chimpanzees, helminths, host parasite relationships, fecal examination, characterization, developmental stages, ribosomal RNA, mitochondrial DNA Tag der Promotion: 10.06.2015 Contents I INTRODUCTION ---------------------------------------------------- 1- 4 I.1 Background 1- 3 I.2 Study objectives 4 II LITERATURE OVERVIEW --------------------------------------- 5- 37 II.1 Taï National Park 5- 7 II.1.1 Location and climate 5- 6 II.1.2 Vegetation and fauna 6 II.1.3 Human pressure and impact on the park 7 II.2 Chimpanzees 7- 12 II.2.1 Status 7 II.2.2 Group sizes and composition 7- 9 II.2.3 Territories and ranging behavior 9 II.2.4 Diet and hunting behavior 9- 10 II.2.5 Contact with humans 10 II.2.6 -

Biology Two DOL38 - 41

III. Phylum Platyhelminthes A. General characteristics All About Worms! 1. flat worms a. distinct head & tail ends 2. bilateral symmetry 3. habitat = free-living aquatic or parasitic *a. Parasite = heterotroph that gets its nutrients from the living organisms in/on which they live Ph. Platyhelminthes Ph. Nematoda Ph. Annelida 4. motile 5. carnivores or detritivores 6. reproduce sexually & asexually Biology Two DOL38 - 41 7/4/2016 B. Anatomy 3. Simple nervous system 1. have 3 body layers w/ true tissues a. brain-like ganglia in head & organs b. 2 longitudinal nerves with a. inner = endoderm transverse nerves across body b. middle = mesoderm 4. Lack respiratory, circulatory systems c. outer = ectoderm 5. Parasitic forms lack digestive & excretory systems 2. are acoelomates - lack a coelom around internal organs a. use diffusion to supply needs from host organisms a. digestive tract is formed of endoderm 6. Planaria anat. 7. Tapeworm anat. a. flat body w/ arrow-shaped head & a. head = scolex tapered tail 1) has hooks to help hold onto host b. light-sensitive eyespots on head 2) has suckers to ingest food c. body covered in cilia & mucus to aid b. body segments = proglottids movement 1) new ones form right behind head d. digestive tract only open at mouth 2) each segment produces gametes 1) in center of ventral surface 3) each houses excretory organs 2) used for feeding, excretion C. Physiology 1. Digestion (free-living) a. pharynx extends out of mouth b. sucks food into intestines for digestion c. excretory pores & mouth/pharynx remove wastes 2. Reproduction varies a. Sexual for free-living (& some parasites) 1) hermaphrodites a) cross-fertilize or self-fertilize internally b. -

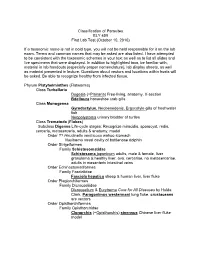

Classification of Parasites BLY 459 First Lab Test (October 10, 2010)

Classification of Parasites BLY 459 First Lab Test (October 10, 2010) If a taxonomic name is not in bold type, you will not be held responsible for it on the lab exam. Terms and common names that may be asked are also listed. I have attempted to be consistent with the taxonomic schemes in your text as well as to list all slides and live specimens that were displayed. In addition to highlighted taxa, be familiar with, material in lab handouts (especially proper nomenclature), lab display sheets, as well as material presented in lecture. Questions about vectors and locations within hosts will be asked. Be able to recognize healthy from infected tissue. Phylum Platyhelminthes (Flatworms) Class Turbellaria Dugesia (=Planaria ) Free-living, anatomy, X-section Bdelloura horseshoe crab gills Class Monogenea Gyrodactylus , Neobenedenis, Ergocotyle gills of freshwater fish Neopolystoma urinary bladder of turtles Class Trematoda ( Flukes ) Subclass Digenea Life-cycle stages: Recognize miracidia, sporocyst, redia, cercaria , metacercaria, adults & anatomy, model Order ?? Hirudinella ventricosa wahoo stomach Nasitrema nasal cavity of bottlenose dolphin Order Strigeiformes Family Schistosomatidae Schistosoma japonicum adults, male & female, liver granuloma & healthy liver, ova, cercariae, no metacercariae, adults in mesenteric intestinal veins Order Echinostomatiformes Family Fasciolidae Fasciola hepatica sheep & human liver, liver fluke Order Plagiorchiformes Family Dicrocoeliidae Dicrocoelium & Eurytrema Cure for All Diseases by Hulda Clark, Paragonimus -

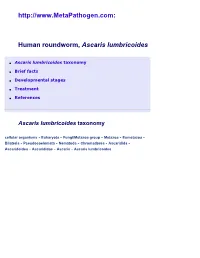

Ascaris Lumbricoides, Roundworm, Causative Agent Of

http://www.MetaPathogen.com: Human roundworm, Ascaris lumbricoides ● Ascaris lumbricoides taxonomy ● Brief facts ● Developmental stages ● Treatment ● References Ascaris lumbricoides taxonomy cellular organisms - Eukaryota - Fungi/Metazoa group - Metazoa - Eumetazoa - Bilateria - Pseudocoelomata - Nematoda - Chromadorea - Ascaridida - Ascaridoidea - Ascarididae - Ascaris - Ascaris lumbricoides Brief facts ● Together with human hookworms (Ancylostoma duodenale and Necator americanus also described at MetaPathogen) and whipworms (Trichuris trichiura), Ascaris lumbricoides (human roundworms) belong to a group of so-called soil-transmitted helminths that represent one of the world's most important causes of physical and intellectual growth retardation. ● Today, ascariasis is among the most important tropical diseases in humans with more than billion infected people world-wide. Ascariasis is mostly seen in tropical and subtropical countries because of warm and humid conditions that facilitate development and survival of eggs. The majority of infections occur in Asia (up to 73%), followed by Africa (~12%) and Latin America (~8%). ● Ascaris lumbricoides is one of six worms listed and named by Linnaeus. Its name has remained unchanged up to date. ● Ascariasis is an ancient infection, and A. lumbricoides have been found in human remains from Peru dating as early as 2277 BC. There are records of A. lumbricoides in Egyptian mummy dating from 1938 to 1600 BC. Despite of long history of awareness and scientific observations, the parasite's life cycle in humans, including the migration of the larval stages around the body, was discovered only in 1922 by a Japanese pediatrician, Shimesu Koino. ● Unlike the hookworm, whose third-stage (L3) larvae actively penetrate skin, A. lumbricoides (as well as T. trichiura) is transmitted passively within the eggs after being swallowed by the host as a result of fecal contamination. -

Tissue Nematode: Trichenella Spiralis

Tissue nematode: Trichenella spiralis Introduction Trichinella spiralis is a viviparous nematode parasite, occurring in pigs, rodents, bears, hyenas and humans, and is liable for the disease trichinosis. It is occasionally referred to as the "pork worm" as it is characteristically encountered in undercooked pork foodstuffs. It should not be perplexed with the distantly related pork tapeworm. Trichinella species, the small nematode parasite of individuals, have an abnormal lifecycle, and are one of the most extensive and clinically significant parasites in the whole world. The adult worms attain maturity in the small intestine of a definitive host, such as pig. Each adult female gives rise to batches of live larvae, which bore across the intestinal wall, enter the blood stream (to feed on it) and lymphatic system, and are passed to striated muscle. Once reaching to the muscle, they encyst, or become enclosed in a capsule. Humans can become infected by eating contaminated pork, horse meat, or wild carnivorus animals such as cat, fox, or bear. Epidemology Trichinosis is a disease caused by the worm. It occurs around most parts of the world, and infects majority of humans. It ranges from North America and Europe, to Japan, China and Tropical Africa. Morphology Males of T. spiralis measure about1.4 and 1.6 mm long, and are more flat at anterior end than posterior end. The anus is seen in the terminal position, and they have a large copulatory pseudobursa on both the side. The females of T. spiralis are nearly twice the size of the males, and have an anal aperture situated terminally. -

Kinomes of Selected Parasitic Helminths - Fundamental and Applied Implications

KINOMES OF SELECTED PARASITIC HELMINTHS - FUNDAMENTAL AND APPLIED IMPLICATIONS Andreas Julius Stroehlein BSc (Bingen am Rhein, Germany) MSc (Berlin, Germany) ORCID ID 0000-0001-9432-9816 Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy July 2017 Melbourne Veterinary School, Faculty of Veterinary and Agricultural Sciences, The University of Melbourne Produced on archival quality paper ii SUMMARY ________________________________________________________________ Worms (helminths) are a large, paraphyletic group of organisms including free-living and parasitic representatives. Among the latter, many species of roundworms (phylum Nematoda) and flatworms (phylum Platyhelminthes) are of major socioeconomic importance worldwide, causing debilitating diseases in humans and livestock. Recent advances in molecular technologies have allowed for the analysis of genomic and transcriptomic data for a range of helminth species. In this context, studying molecular signalling pathways in these species is of particular interest and should help to gain a deeper understanding of the evolution and fundamental biology of parasitism among these species. To this end, the objective of the present thesis was to characterise and curate the protein kinase complements (kinomes) of parasitic worms based on available transcriptomic data and draft genome sequences using a bioinformatic workflow in order to increase our understanding of how kinase signalling regulates fundamental biology and also to gain new insights into the evolution of protein kinases in parasitic worms. In addition, this work also aimed to investigate protein kinases with regard to their potential as useful targets for the development of novel anthelmintic small-molecule agents. This thesis consists of a literature review, four chapters describing original research findings and a general discussion. -

New Aspects of Human Trichinellosis: the Impact of New Trichinella Species F Bruschi, K D Murrell

15 REVIEW Postgrad Med J: first published as 10.1136/pmj.78.915.15 on 1 January 2002. Downloaded from New aspects of human trichinellosis: the impact of new Trichinella species F Bruschi, K D Murrell ............................................................................................................................. Postgrad Med J 2002;78:15–22 Trichinellosis is a re-emerging zoonosis and more on anti-inflammatory drugs and antihelminthics clinical awareness is needed. In particular, the such as mebendazole and albendazole; the use of these drugs is now aided by greater clinical description of new Trichinella species such as T papuae experience with trichinellosis associated with the and T murrelli and the occurrence of human cases increased number of outbreaks. caused by T pseudospiralis, until very recently thought to The description of new Trichinella species, such as T murrelli and T papuae, as well as the occur only in animals, requires changes in our handling occurrence of outbreaks caused by species not of clinical trichinellosis, because existing knowledge is previously recognised as infective for humans, based mostly on cases due to classical T spiralis such as T pseudospiralis, now render the clinical picture of trichinellosis potentially more compli- infection. The aim of the present review is to integrate cated. Clinicians and particularly infectious dis- the experiences derived from different outbreaks around ease specialists should consider the issues dis- the world, caused by different Trichinella species, in cussed in this review when making a diagnosis and choosing treatment. order to provide a more comprehensive approach to diagnosis and treatment. SYSTEMATICS .......................................................................... Trichinellosis results from infection by a parasitic nematode belonging to the genus trichinella. -

"Structure, Function and Evolution of the Nematode Genome"

Structure, Function and Advanced article Evolution of The Article Contents . Introduction Nematode Genome . Main Text Online posting date: 15th February 2013 Christian Ro¨delsperger, Max Planck Institute for Developmental Biology, Tuebingen, Germany Adrian Streit, Max Planck Institute for Developmental Biology, Tuebingen, Germany Ralf J Sommer, Max Planck Institute for Developmental Biology, Tuebingen, Germany In the past few years, an increasing number of draft gen- numerous variations. In some instances, multiple alter- ome sequences of multiple free-living and parasitic native forms for particular developmental stages exist, nematodes have been published. Although nematode most notably dauer juveniles, an alternative third juvenile genomes vary in size within an order of magnitude, com- stage capable of surviving long periods of starvation and other adverse conditions. Some or all stages can be para- pared with mammalian genomes, they are all very small. sitic (Anderson, 2000; Community; Eckert et al., 2005; Nevertheless, nematodes possess only marginally fewer Riddle et al., 1997). The minimal generation times and the genes than mammals do. Nematode genomes are very life expectancies vary greatly among nematodes and range compact and therefore form a highly attractive system for from a few days to several years. comparative studies of genome structure and evolution. Among the nematodes, numerous parasites of plants and Strikingly, approximately one-third of the genes in every animals, including man are of great medical and economic sequenced nematode genome has no recognisable importance (Lee, 2002). From phylogenetic analyses, it can homologues outside their genus. One observes high rates be concluded that parasitic life styles evolved at least seven of gene losses and gains, among them numerous examples times independently within the nematodes (four times with of gene acquisition by horizontal gene transfer. -

Trichinellosis Surveillance — United States, 2002–2007

Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report www.cdc.gov/mmwr Surveillance Summaries December 4, 2009 / Vol. 58 / No. SS-9 Trichinellosis Surveillance — United States, 2002–2007 Department Of Health And Human Services Centers for Disease Control and Prevention MMWR CONTENTS The MMWR series of publications is published by Surveillance, Epidemiology, and Laboratory Services, Centers for Disease Control Introduction .............................................................................. 2 and Prevention (CDC), U.S. Department of Health and Human Methods ................................................................................... 2 Services, Atlanta, GA 30333. Results ...................................................................................... 2 Suggested Citation: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Title]. Surveillance Summaries, [Date]. MMWR 2009;58(No. SS-#). Discussion................................................................................. 5 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Conclusion ................................................................................ 7 Thomas R. Frieden, MD, MPH References ................................................................................ 7 Director Appendix ................................................................................. 8 Peter A. Briss, MD, MPH Acting Associate Director for Science James W. Stephens, PhD Office of the Associate Director for Science Stephen B. Thacker, MD, MSc Acting Deputy Director for Surveillance, Epidemiology, -

The Ubiquitin Proteasome System Is Required for Cell Proliferation of The

RESEARCH ARTICLE 3257 Development 137, 3257-3268 (2010) doi:10.1242/dev.053124 © 2010. Published by The Company of Biologists Ltd The ubiquitin proteasome system is required for cell proliferation of the lens epithelium and for differentiation of lens fiber cells in zebrafish Fumiyasu Imai1, Asuka Yoshizawa1, Noriko Fujimori-Tonou2, Koichi Kawakami3 and Ichiro Masai1,* SUMMARY In the developing vertebrate lens, epithelial cells differentiate into fiber cells, which are elongated and flat in shape and form a multilayered lens fiber core. In this study, we identified the zebrafish volvox (vov) mutant, which shows defects in lens fiber differentiation. In the vov mutant, lens epithelial cells fail to proliferate properly. Furthermore, differentiating lens fiber cells do not fully elongate, and the shape and position of lens fiber nuclei are affected. We found that the vov mutant gene encodes Psmd6, the subunit of the 26S proteasome. The proteasome regulates diverse cellular functions by degrading polyubiquitylated proteins. Polyubiquitylated proteins accumulate in the vov mutant. Furthermore, polyubiquitylation is active in nuclei of differentiating lens fiber cells, suggesting roles of the proteasome in lens fiber differentiation. We found that an E3 ubiquitin ligase anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome (APC/C) is involved in lens defects in the vov mutant. These data suggest that the ubiquitin proteasome system is required for cell proliferation of lens epithelium and for the differentiation of lens fiber cells in zebrafish. KEY WORDS: Ubiquitin, Proteasome, Lens, Zebrafish, Psmd6, APC/C INTRODUCTION acid DNase (DLAD; Dnase2b). However, it is unclear how lens During development, the lens placode delaminates from the morphogenesis and organelle loss are related to these transcription epidermal ectoderm and forms the lens vesicle. -

The Transcriptome of Trichuris Suis – First Molecular Insights Into a Parasite with Curative Properties for Key Immune Diseases of Humans

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ResearchOnline at James Cook University The Transcriptome of Trichuris suis – First Molecular Insights into a Parasite with Curative Properties for Key Immune Diseases of Humans Cinzia Cantacessi1*, Neil D. Young1, Peter Nejsum2, Aaron R. Jex1, Bronwyn E. Campbell1, Ross S. Hall1, Stig M. Thamsborg2, Jean-Pierre Scheerlinck1,3, Robin B. Gasser1* 1 Department of Veterinary Science, The University of Melbourne, Parkville, Victoria, Australia, 2 Departments of Veterinary Disease Biology and Basic Animal and Veterinary Science, University of Copenhagen, Frederiksberg, Denmark, 3 Centre for Animal Biotechnology, The University of Melbourne, Parkville, Australia Abstract Background: Iatrogenic infection of humans with Trichuris suis (a parasitic nematode of swine) is being evaluated or promoted as a biological, curative treatment of immune diseases, such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and ulcerative colitis, in humans. Although it is understood that short-term T. suis infectioninpeoplewithsuchdiseases usually induces a modified Th2-immune response, nothing is known about the molecules in the parasite that induce this response. Methodology/Principal Findings: As a first step toward filling the gaps in our knowledge of the molecular biology of T. suis, we characterised the transcriptome of the adult stage of this nematode employing next-generation sequencing and bioinformatic techniques. A total of ,65,000,000 reads were generated and assembled into -

Good Manufacturing Practices For

Good Manufacturing Practices for Fermented Dry & Semi-Dry Sausage Products by The American Meat Institute Foundation October 1997 ANALYSIS OF MICROBIOLOGICAL HAZARDS ASSOCIATED WITH DRY AND SEMI-DRY SAUSAGE PRODUCTS Staphylococcus aureus The Microorganism Staphylococcus aureus is often called "staph." It is present in the mucous membranes--nose and throat--and on skin and hair of many healthy individuals. Infected wounds, lesions and boils are also sources. People with respiratory infections also spread the organism by coughing and sneezing. Since S. aureus occurs on the skin and hides of animals, it can contaminate meat and by-products by cross-contamination during slaughter. Raw foods are rarely the source of staphylococcal food poisoning. Staphylococci do not compete very well with other bacteria in raw foods. When other competitive bacteria are removed by cooking or inhibited by salt, S. aureus can grow. USDA's Nationwide Data Collection Program for Steers and Heifers (1995) and Nationwide Pork Microbiological Baseline Data Collection Program: Market Hogs (1996) reported that S. aureus was recovered from 4.2 percent of 2,089 carcasses and 16 percent of 2,112 carcasses, respectively. Foods high in protein provide a good growth environment for S. aureus, especially cooked meat/meat products, poultry, fish/fish products, milk/dairy products, cream sauces, salads with ham, chicken, potato, etc. Although salt or sugar inhibit the growth of some microorganisms, S. aureus can grow in foods with low water activity, i.e., 0.86 under aerobic conditions or 0.90 under anaerobic conditions, and in foods containing high concentrations of salt or sugar. S.