Identity Salience and Opposition to Hydropower Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Detailed Report on Implementation of Catchment Area Treatment Plan of Teesta Stage-V Hydro-Electric Power Project (510Mw) Sikkim

A DETAILED REPORT ON IMPLEMENTATION OF CATCHMENT AREA TREATMEN PLAN OF TEESTA STAGE-V HYDRO-ELECTRIC POWER PROJECT (510MW) SIKKIM - 2007 FOREST, ENVIRONMENT & WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT DEPARTMENT GOVERNMENT OF SIKKIM GANGTOK A DETAILED REPORT ON IMPLEMENTATION OF CATCHMENT AREA TREATMENT PLAN OF TEESTA STAGE-V HYDRO-ELECTRIC POWER PROJECT (510MW) SIKKIM FOREST, ENVIRONMENT & WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT DEPARTMENT GOVERNMENT OF SIKKIM GANGTOK BRIEF ABOUT THE ENVIRONMENT CONSERVATION OF TEESTA STAGE-V CATCHMENT. In the Eastern end of the mighty Himalayas flanked by Bhutan, Nepal and Tibet on its end lays a tiny enchanting state ‘Sikkim’. It nestles under the protective shadow of its guardian deity, the Mount Kanchendzonga. Sikkim has witnessed a tremendous development in the recent past year under the dynamic leadership of Honorable Chief Minister Dr.Pawan Chamling. Tourism and Power are the two thrust sectors which has prompted Sikkim further in the road of civilization. The establishment of National Hydro Project (NHPC) Stage-V at Dikchu itself speaks volume about an exemplary progress. Infact, an initiative to treat the land in North and East districts is yet another remarkable feather in its cap. The project Catchment Area Treatment (CAT) pertains to treat the lands by various means of action such as training of Jhoras, establishing nurseries and running a plantation drive. Catchment Area Treatment (CAT) was initially started in the year 2000-01 within a primary vision to control the landslides and to maintain an ecological equilibrium in the catchment areas with a gestation period of nine years. Forests, Environment & Wildlife Management Department, Government of Sikkim has been tasked with a responsibility of nodal agency to implement catchment area treatment programme by three circle of six divisions viz, Territorial, Social Forestry followed by Land Use & Environment Circle. -

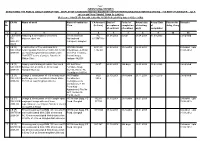

Date of Acceptance of Contract Period of Completion Of

Page 1 (SENSITIZING REPORT) SENSITIZING THE PUBLIC ABOUT CORRUPTION - DISPLAY OF STANDARD NOTICE BOARD BY DEPARTMENTS/ORGANISATION REGARDING : 764 BRTF (P) SWASTIK : JULY 2012 (CONTRACT MORE THAN 50 LAKHS) (Reference HQ CE (P) Swastik letter No.16500/Policy/69/Vig dated 10 Dec 2009) S/ CA No Name of work Name of contractor CA Amount Date of Period of Actual date Actual Date Reason for Remarks No /Firm (In Lacs) acceptance completion of starting of delay, if any of contract of contract work completion 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 1 CE(P)/SW Handling & conveyance of cement, The G.M Sikkim Rs. 01.04.2008 1 year 01.04.2008 31.03.2009 Completed TK/ bitumen, steel etc Nationalised 8.17/MT/Km MOT-01/ Transport, Gangtok 08-09 2 CE (P) Construction of Toe walls and RCC M/S Shiv Shakti 2891.21/ 28.08.2008 15 months 02.09.2008 - Extended upto SWTK/02/ retaining walls from Km 24.00 to Km 51.00 Enterprises, A-340/2, 1792.50 31.03.2012 2008-09 on Road Gangtok-Nathula (JNM) under Near P & T Colony, 764 BRTF sector of project Swastik In Shastri Nagar, Sikkim State. Jodhpur-342003 3 CE (P) Supply and stacking of coarse river sand M/s Anil Steel 92.57 29.08.2008 120 days 02.09.2009 15.04.2009 Completed SWTK/03/ between km 24.00 to 51.00 on road Furniture, Shop 2008-09 Gangtok-Nathula No.150, Sector 7C, Chandigarh-160026 4 CE (P) Design & construction of 110 m long major M/S Poddar 892/ 25.10.2008 24 months 24.11.2008 23.11.2010 Completed SWTK/07/ pmt bridge over river Dikchu-Khola at km Construction 899.5 2008-09 31.103 on road Singtham-Dikchu Co;Engineers -

List of Bridges in Sikkim Under Roads & Bridges Department

LIST OF BRIDGES IN SIKKIM UNDER ROADS & BRIDGES DEPARTMENT Sl. Total Length of District Division Road Name Bridge Type No. Bridge (m) 1 East Singtam Approach road to Goshkan Dara 120.00 Cable Suspension 2 East Sub - Div -IV Gangtok-Bhusuk-Assam lingz 65.00 Cable Suspension 3 East Sub - Div -IV Gangtok-Bhusuk-Assam lingz 92.50 Major 4 East Pakyong Ranipool-Lallurning-Pakyong 33.00 Medium Span RC 5 East Pakyong Ranipool-Lallurning-Pakyong 19.00 Medium Span RC 6 East Pakyong Ranipool-Lallurning-Pakyong 26.00 Medium Span RC 7 East Pakyong Rongli-Delepchand 17.00 Medium Span RC 8 East Sub - Div -IV Gangtok-Bhusuk-Assam lingz 17.00 Medium Span RC 9 East Sub - Div -IV Penlong-tintek 16.00 Medium Span RC 10 East Sub - Div -IV Gangtok-Rumtek Sang 39.00 Medium Span RC 11 East Pakyong Ranipool-Lallurning-Pakyong 38.00 Medium Span STL 12 East Pakyong Assam Pakyong 32.00 Medium Span STL 13 East Pakyong Pakyong-Machung Rolep 24.00 Medium Span STL 14 East Pakyong Pakyong-Machung Rolep 32.00 Medium Span STL 15 East Pakyong Pakyong-Machung Rolep 31.50 Medium Span STL 16 East Pakyong Pakyong-Mamring-Tareythan 40.00 Medium Span STL 17 East Pakyong Rongli-Delepchand 9.00 Medium Span STL 18 East Singtam Duga-Pacheykhani 40.00 Medium Span STL 19 East Singtam Sangkhola-Sumin 42.00 Medium Span STL 20 East Sub - Div -IV Gangtok-Bhusuk-Assam lingz 29.00 Medium Span STL 21 East Sub - Div -IV Penlong-tintek 12.00 Medium Span STL 22 East Sub - Div -IV Penlong-tintek 18.00 Medium Span STL 23 East Sub - Div -IV Penlong-tintek 19.00 Medium Span STL 24 East Sub - Div -IV Penlong-tintek 25.00 Medium Span STL 25 East Sub - Div -IV Tintek-Dikchu 12.00 Medium Span STL 26 East Sub - Div -IV Tintek-Dikchu 19.00 Medium Span STL 27 East Sub - Div -IV Tintek-Dikchu 28.00 Medium Span STL 28 East Sub - Div -IV Gangtok-Rumtek Sang 25.00 Medium Span STL 29 East Sub - Div -IV Rumtek-Rey-Ranka 53.00 Medium Span STL Sl. -

LTOA-Minutes

Minutes of Meeting in regard to Connectivity / Open Access with constituents of Eastern Region held on 08-02-2012 at NRPC, Delhi List of participants is enclosed at Annexure-1. OPTCL initiated the discussion regarding the transmission system planned under open access/connectivity for generation projects in Orissa and stated that the transmission system need to be planned in a coordinate manner in order to take care of evacuation arrangement for delivery of the States’ share from the generation projects. After several rounds of discussion, it was concluded that there would be no change in the transmission system planned for Phase-I generation projects in Orissa which is already under implementation. The transmission system for phase-II generation projects in Orissa is being reviewed in consultation with OPTCL. Accordingly, it was decided that the Open Acess/LTA cases for the generation projects other than Orissa Phase-II projects would be discussed in the present meeting. The details of the deliberation in this regard is given below : 1.0 Connectivity / Open Access for Phase-II Generation Projects in Jharkhand, Bihar and West Bengal of Eastern Region POWERGRID explained the details of the Phase-II generation projects in Jharkhand, Bihar and West Bengal who have applied for connectivity/open access for transfer of power to various beneficiaries. The status of above projects was discussed in a meeting for Connectivity and Long Term Access held on 29-07-2011 at POWERGRID office, Gurgaon. Keeping in view the progress of above projects, it was decided to discuss some of the projects in the present Standing Committee meeting. -

An Assessment of Dams in India's North East Seeking Carbon Credits from Clean Development Mechanism of the United Nations Fram

AN ASSESSMENT OF DAMS IN INDIA’S NORTH EAST SEEKING CARBON CREDITS FROM CLEAN DEVELOPMENT MECHANISM OF THE UNITED NATIONS FRAMEWORK CONVENTION ON CLIMATE CHANGE A Report prepared By Mr. Jiten Yumnam Citizens’ Concern for Dams and Development Paona Bazar, Imphal Manipur 795001 E-add: [email protected], [email protected] February 2012 Supported by International Rivers CONTENTS I INTRODUCTION: OVERVIEW OF DAMS AND CDM PROJECTS IN NORTH EAST II BRIEF PROJECT DETAILS AND KEY ISSUES AND CHALLENGES PERTAINING TO DAM PROJECTS IN INDIA’S NORTH EAST SEEKING CARBON CREDITS FROM CDM MECHANISM OF UNFCCC 1. TEESTA III HEP, SIKKIM 2. TEESTA VI HEP, SIKKIM 3. RANGIT IV HEP, SIKKIM 4. JORETHANG LOOP HEP, SIKKIM 5. KHUITAM HEP, ARUNACHAL PRADESH 6. LOKTAK HEP, MANIPUR 7. CHUZACHEN HEP, SIKKIM 8. LOWER DEMWE HEP, ARUNACHAL PRADESH 9. MYNTDU LESHKA HEP, MEGHALAYA 10. TING TING HEP, SIKKIM 11. TASHIDING HEP, SIKKIM 12. RONGNINGCHU HEP, SIKKIM 13. DIKCHU HEP, SIKKIM III KEY ISSUES AND CHALLENGES OF DAMS IN INDIA’S NORTH EAST SEEKING CARBON CREDIT FROM CDM IV CONCLUSIONS V RECOMMENDATIONS VI ANNEXURES A) COMMENTS AND SUBMISSIONS TO CDM EXECUTIVE BOARD ON DAM PROJECTS FROM INDIA’S NORTH EAST SEEKING REGISTRATION B) MEDIA COVERAGES OF MYNTDU LESHKA DAM SEEKING CARBON CREDITS FROM CDM OF UNFCCC GLOSSARY OF TERMS ACT: Affected Citizens of Teesta CDM: Clean Development Mechanism CC : Carbon Credits CER: Certified Emissions Reductions CWC: Central Water Commission DPR: Detailed Project Report DOE: Designated Operating Entity DNA: Designated Nodal Agency EAC: -

GANGTOK (Civil Extraordinary Jurisdiction)

THE HIGH COURT OF SIKKIM : GANGTOK (Civil Extraordinary Jurisdiction) ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ D.B.: THE HON’BLE MR. JUSTICE JITENDRA KUMAR MAHESHWARI, C.J. THE HON’BLE MR. JUSTICE BHASKAR RAJ PRADHAN, JUDGE ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- W.P. (PIL) No. 04 of 2017 In Re: Release of Water from Dikchu Hydelpower Project. .... Petitioner. Versus 1. The Chief Secretary, Government of Sikkim, Gangtok. 2. The Home Secretary, Government of Sikkim, Gangtok. 3. The District Collector, East District, Gangtok. 4. Mr. Niladri Mondal, Plant Head, Sneha Kinetic Power Project Ltd., D.H.E.P. 96 MW East Sikkim. 5. National Hydroelectric Power Corpn. Ltd., Teesta Stage-V Balutar, Sirwani Singtam, East Sikkim. 6. General Manager, Teesta State III. Hydro Power at Chungthang, North Sikkim 7. The Director, Shiga Energy Ltd., Implementing company of Tashiding, Hydroelectric Project at Lower Kabithang, Labing, West Sikkim. 8. The General Manager, National Hydroelectric Power Project at Hingdam, Tashiding Road, South Sikkim. 2 W. P. (PIL) No. 04 of 2017 In Re: Release of Water from Dikchu Hydelpower Project v. Chief Secretary & Ors. 9. Site Incharge/Plant Incharge, O and M, Dans Energy Private Limited, Chisopaney, South Sikkim. 10. Site Incharge/Plant Incharge, O and M. Chuzachen Hydro Electric Project At Rangpo and Rongli, East Sikkim. 11. Site Incharge/Plant Incharge, O and M. Rongli Dam at Rongli, East Sikkim. ….. Respondents. ---------------------------------------------------------------------------- Appearance: Mr. N. Rai, Senior Advocate as Amicus Curiae. Dr. Doma T. Bhutia, Additional Advocate General with Mr. S. K. Chettri, Government Advocate for the Respondent nos.1 to 3. Mr. Tashi Rapten Barfungpa, Advocate for the respondent no.4. Mr. A. K. -

Minutes of Mom Rangpo SPS Review 290317

Eastern Regional Power Committee, Kolkata Minutes of Special Meeting to review the limit of maximum power flow through 400kV Rangpo – Siliguri D/c line in respect of Rangpo SPS held on 29th March, 2017 at ERPC, Kolkata List of participants is at Annexure-A. Member Secretary, ERPC welcomed all the participants to the special meeting. He informed that this special meeting was convened in continuation to the special meeting held on 14.10.2016 and 30.11.2016 at ERPC, Kolkata to review the limit of maximum power flow through 400kV Rangpo – Siliguri D/c line in respect of SPS at 400kV level at Rangpo S/s for reliable power evacuation. It was informed that the meeting was convened on the request of Teesta Urja after the declaration of COD of their all six units. Following issues were discussed: 1. Progress of Rangpo – Kishanganj 400kV D/c (Quad) line: Teesta valley Power Transmission Ltd. (TPTL) updated the progress of Rangpo – Kishanganj 400kV D/c (Quad) line as given below: Total Completed Locations/Foundation 591 521 Erection 591 511 Stringing 215km 145km It was informed that the work is getting delayed due to severe ROW issues nearby Darjeeling (Gorkhaland) area. During the meeting held on 30.11.2016, it was intimated that the line would be completed by March 17. However, the line is now expected to be commissioned by October, 2017 as mentioned by TPTL. On query, it was informed that contract was awarded in November, 2009 but the work got delayed due to land issues and finally the work started in 2012 after the MoU with Govt. -

CENTRAL ELECTRICITY REGULATORY COMMISSION NEW DELHI Petition No. 10/SM/2017 Coram: Shri P. K. Pujari, Chairperson Dr. M. K

CENTRAL ELECTRICITY REGULATORY COMMISSION NEW DELHI Petition No. 10/SM/2017 Coram: Shri P. K. Pujari, Chairperson Dr. M. K. Iyer, Member Date of Order: 21st of February, 2019 In the matter of Non-compliance of the provision of the Central Electricity Regulatory Commission (Procedure, Terms and Conditions for grant of Transmission Licence and other related matters) Regulations, 2009 And In the matter of Teestavellay Power Transmission Limited 2nd Floor, Vijaya Building 17, Barakhamba Road New Delhi-110 001 ....Respondent Parties present: 1) Sh. Tarun Johri, Advocate, TPTL 2) Shri Ankur Gupta, Advocate, TPTL 3) Ms. Swapna Seshadri, Advocate Dans Energy 4) Shri Piyush Shandilya, TPTL 5) S. K. Bhowmick, TPTL ORDER The Commission, vide order dated 22nd June, 2017 in Petition No. 10/SM/2017, observed as under: “By order dated 14.5.2009 in Petition No. 116/2008, Teestavalley Power Transmission Ltd. (the licensee), an SPV, and a joint venture between POWERGRID and Teesta Urja Ltd. (TUL) was granted transmission license to execute the following transmission system: Order in Petition No. 10/SM/2017 Page 1 Sl. No. Description Length 1. 400 kV D/C transmission line with quad Moose 2 km conductor from Teesta-III generating station to Mangan Pooling Station. 2. 400 kV D/C transmission line with quad Moose 204 km conductor from Mangan to new pooling station at Kishanganj including 2 line bays and 2 nos. 63 MVAR Reactors at Kishanganj switchyard 2. As per Annexure 2 of BPTA dated 24.2.2010 entered into between POWERGRID and seven LTTCs for LTA, Teesta III-Mangan and Mangan- Kishanganj 400 kV D/C with quad moose conductor along with associated line bays was required to be completed on or before August, 2011 along with Teesta-III generation project. -

Assessment of Hydromorphological Conditions of Upper and Lower Dams of River Teesta in Sikkim

Journal of Spatial Hydrology Volume 15 Number 2 Article 1 2019 Assessment of hydromorphological conditions of upper and lower dams of river Teesta in Sikkim Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/josh BYU ScholarsArchive Citation (2019) "Assessment of hydromorphological conditions of upper and lower dams of river Teesta in Sikkim," Journal of Spatial Hydrology: Vol. 15 : No. 2 , Article 1. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/josh/vol15/iss2/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Spatial Hydrology by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Journal of Spatial Hydrology Vol.15, No.2 Fall 2019 Assessment of hydromorphological conditions of upper and lower dams of river Teesta in Sikkim Deepak Sharma1, Ishwarjit Elangbam Singh2, Kalosona Paul3 & Somnath Mukherjee4 1 Doctoral Fellow, Department of Geography, Sikkim University, Gangtok, Sikkim 2Assistant Professor, Department of Geography, Sikkim University, Gangtok, Sikkim 3Assistant Professor, Department of Geography, Sidho-Kanho-Birsha University, Purulia, West Bengal 4Assistant Professor, Department of Geography, Bankura Christian College, Bankura, West Bengal Abstract River is a main source of fresh water. Although since past river water and basin morphology both have affected and changed by some natural and human induced activities. Human civilization since time immemorial has been rooted close to river basin. Changing morphology of a river channel has done also by natural causes. The hydromorphological state of a river system replicates its habitat quality and relies on a variety of both physical and human features. -

Mobile Subjects, Markets, and Sovereignty in the India-Nepal Borderland, 1780-1930

Shifting States: Mobile Subjects, Markets, and Sovereignty in the India-Nepal Borderland, 1780-1930 Catherine Warner A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2014 Committee: Anand Yang, Chair Purnima Dhavan Priti Ramamurthy Program Authorized to Offer Degree: History © Copyright 2014 Catherine Warner University of Washington Abstract Shifting States: Mobile Subjects, Markets, and Sovereignty in the India-Nepal Borderland, 1780-1930 Catherine Warner Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Dr. Anand Yang International Studies and History This dissertation analyzes the creation of the India-Nepal borderland and changing terms of sovereignty, subjectivity and political belonging from the margins of empire in South Asia from 1780 to 1930. I focus on particular instances of border crossing in each chapter, beginning with the exile of deposed sovereigns of small states that spanned the interface of the lower Himalayan foothills and Gangetic plains in the late eighteenth century. The flight of exiled sovereigns and the varied terms of their resettlement around the border region—a process spread over several decades—proved as significant in defining the new borderland between the East India Company and Nepal as the treaty penned after the Anglo-Nepal War of 1814 to 1816. Subsequent chapters consider cross-border movements of bandits, shifting cultivators, soldiers, gendered subjects, laborers, and, later, a developing professional class who became early Nepali nationalist spokesmen. Given that the India-Nepal border remained open without a significant military presence throughout the colonial and even into the contemporary period, I argue that ordinary people engaged with and shaped forms of political belonging and subject status through the always present option of mobility. -

Disaster Management Plan-(2020-21) East Sikkim-737101

DISASTER MANAGEMENT PLAN-(2020-21) EAST SIKKIM-737101 Prepared by: District Disaster Management Authority, East District Collectorate, East Sichey, Gangtok 1 FOREWORD Recent disasters, including the Earthquake which occurred on 18th September 2011 have compelled us to review our Disaster Management Plan and make it more stakeholders friendly. It is true that all the disasters have been dealt significantly by the state ensuring least damage to the human life and property. However, there is a need to generate a system which works automatically during crisis and is based more on the need of the stakeholders specially the community. Further a proper co-ordination is required to manage disasters promptly. Considering this we have made an attempt to prepare a Disaster Management Plan in different versions to make it more user-friendly. While the comprehensive Disaster Management Plan based on vulnerability mapping and GIS Mapping and minute details of everything related to management of disasters is underway, we are releasing this booklet separately on the Disaster Management Plan which is basically meant for better coordination among the responders. The Incident Command System is the part of this booklet which has been introduced for the first time in the East District. This booklet is meant to ensure a prompt and properly coordinated effort to respond any crisis. A due care has been taken in preparing this booklet, however any mistakes will be immediately looked into. All the stakeholders are requested to give their feedback and suggestions for further improvements. Lastly, I want to extend my sincere thanks to the Government, the higher authorities and the Relief Commissioner for the support extended to us and especially to my team members including ADM/R, SDM/Gangtok, District Project Officer and Training Officer for the hard work they have put in to prepare this booklet. -

7014414.PDF (8.788Mb)

70-1 4 ,UlU BELFIGLIO, Valentine John, 1934- THE FOREIGN RELATIONS OF INDIA WITH BHUTAN, . SIKKIM AND NEPAL BETWEEN 1947-1967: AN ANALYTICAL FRAMEWORK FOR THE STUDY OF BIG POWER-SMALL POWER RELATIONS. The University of Oklahoma, Ph.D., 1970 Political Science, international law and relations University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan © VALENTINE JOHN BELFIGLIO 1970 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED THIS DISSERTATION HAS BEEN MICROFILMED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED THE UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE THE FOREIGN RELATIONS OF INDIA WITH BHUTAN, SIKKIM AND NEPAL BETWEEN 1947-196?: AN ANALYTICAL FRAMEWORK FOR THE STUDY OF BIG POWER-SMALL POWER RELATIONS A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY BY ,1^ VALENTINE J. BELFIGLIO Norman, Oklahoma 1970 THE FOREIGN RELATIONS OF INDIA WITH BHUTAN, SIKKIM AND NEPAL BETWEEN 1947-196?: AN ANALYTICAL FRAMEWORK FOR THE STUDY OF BIG POWER-SMALL POWER RELATIONS APPROVED BY DISSERTATION COMMITTEE PREFACE The following International Relations study is an effort to provide a new classification tool for the examination of big power-small power relationships. The purpose of the study is to provide definitive categories which may be used in the examination of relationships between nations of varying political power. The rela tionships of India with Bhutan, Sikkim, and Nepal were selected for these reasons. Three different types of relationships each of a distinct and unique nature are evident. Indian- Sikkimese relations provide a situation in which the large power (India) controls the defenses, foreign rela tions and internal affairs of the small power. Indian- Bhutanese relations demonstrates a situation in which the larger power controls the foreign relations of the smaller power, but management over internal affairs and defenses remains in the hands of the smaller nation.