Radiolab and the Micropolitics of Podcasting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

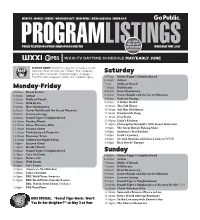

WXXI Program Guide | May 2021

WXXI-TV | WORLD | CREATE | WXXI KIDS 24/7 | WXXI NEWS | WXXI CLASSICAL | WRUR 88.5 SEE CENTER PAGES OF CITY PROGRAMPUBLIC TELEVISION & PUBLIC RADIO FOR ROCHESTER LISTINGSFOR WXXI SHOW MAY/EARLY JUNE 2021 HIGHLIGHTS! WXXI-TV DAYTIME SCHEDULE MAY/EARLY JUNE PLEASE NOTE: WXXI-TV’s daytime schedule listed here runs from 6:00am to 7:00pm. The complete prime time television schedule begins on page 2. Saturday The PBS Kids programs below are shaded in gray. 6:00am Mister Roger’s Neighborhood 6:30am Arthur 7vam Molly of Denali Monday-Friday 7:30am Wild Kratts 6:00am Ready Jet Go! 8:00am Hero Elementary 6:30am Arthur 8:30am Xavier Riddle and the Secret Museum 7:00am Molly of Denali 9:00am Curious George 7:30am Wild Kratts 9:30am A Wider World 8:00am Hero Elementary 10:00am This Old House 8:30am Xavier Riddle and the Secret Museum 10:30am Ask This Old House 9:00am Curious George 11:00am Woodsmith Shop 9:30am Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood 11:30am Ciao Italia 10:00am Donkey Hodie 12:00pm Lidia’s Kitchen 10:30am Elinor Wonders Why 12:30pm Christopher Kimball’s Milk Street Television 11:00am Sesame Street 1:00pm The Great British Baking Show 11:30am Pinkalicious & Peterrific 2:00pm America’s Test Kitchen 12:00pm Dinosaur Train 2:30pm Cook’s Country 12:30pm Clifford the Big Red Dog 3:00pm Second Opinion with Joan Lunden (WXXI) 1:00pm Sesame Street 3:30pm Rick Steves’ Europe 1:30pm Donkey Hodie 2:00pm Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood Sunday 2:30pm Let’s Go Luna! 6:00am Mister Roger’s Neighborhood 3:00pm Nature Cat 6:30am Arthur 3:30pm Wild Kratts 7:00am Molly -

Looking for Podcast Suggestions? We’Ve Got You Covered

Looking for podcast suggestions? We’ve got you covered. We asked Loomis faculty members to share their podcast playlists with us, and they offered a variety of suggestions as wide-ranging as their areas of personal interest and professional expertise. Here’s a collection of 85 of these free, downloadable audio shows for you to try, listed alphabetically with their “recommenders” listed below each entry: 30 for 30 You may be familiar with ESPN’s 30 for 30 series of award-winning sports documentaries on television. The podcasts of the same name are audio documentaries on similarly compelling subjects. Recent podcasts have looked at the man behind the Bikram Yoga fitness craze, racial activism by professional athletes, the origins of the hugely profitable Ultimate Fighting Championship, and the lasting legacy of the John Madden Football video game. Recommended by Elliott: “I love how it involves the culture of sports. You get an inner look on a sports story or event that you never really knew about. Brings real life and sports together in a fantastic way.” 99% Invisible From the podcast website: “Ever wonder how inflatable men came to be regular fixtures at used car lots? Curious about the origin of the fortune cookie? Want to know why Sigmund Freud opted for a couch over an armchair? 99% Invisible is about all the thought that goes into the things we don’t think about — the unnoticed architecture and design that shape our world.” Recommended by Scott ABCA Calls from the Clubhouse Interviews with coaches in the American Baseball Coaches Association Recommended by Donnie, who is head coach of varsity baseball and says the podcast covers “all aspects of baseball, culture, techniques, practices, strategy, etc. -

U.S. PODCAST REPORT TOP 100 PODCASTS by DOWNLOADS Podcasts Ranked by Average Weekly Downloads in the United States Reporting Period: March 16 - April 12, 2020

U.S. PODCAST REPORT TOP 100 PODCASTS BY DOWNLOADS Podcasts Ranked by Average Weekly Downloads in the United States Reporting Period: March 16 - April 12, 2020 # OF NEW RANK PODCAST PODCAST NETWORK SALES REPRESENTATION EPISODES CHANGE 1 NPR News Now NPR National Public Media 672 0 2 Up First NPR National Public Media 30 h2 3 The Ben Shapiro Show Cumulus Media/Westwood One Cumulus Media/Westwood One 22 0 4 My Favorite Murder with Karen Kilgariff Stitcher Midroll 9 i2 and Georgia Hardstark 5 Planet Money NPR National Public Media 11 h3 6 NPR Politics NPR National Public Media 21 h1 7 Fresh Air NPR National Public Media 24 i1 8 Pod Save America RADIO.COM/Cadence13 Cadence 13 8 h1 9 Dateline NBC NBC News Wondery Brand Partnerships 13 i4 10 Indicator from Planet Money NPR National Public Media 20 h3 11 Hidden Brain NPR National Public Media 4 i1 12 Fox News Radio Newscast FOX News Podcasts FOX News Podcasts 672 h4 13 TED Radio Hour NPR National Public Media 5 h1 14 Office Ladies Stitcher Midroll 4 i3 15 How I Built This NPR National Public Media 6 0 16 Wait Wait... Don't Tell Me! NPR National Public Media 5 h5 17 The Dan Bongino Show Cumulus Media/Westwood One Cumulus Media/Westwood One 21 i5 18 Freakonomics Radio Stitcher Midroll 5 h1 19 The Rachel Maddow Show NBC News Wondery Brand Partnerships 21 h1 20 Unlocking Us with Brené Brown RADIO.COM/Cadence13 Cadence13 7 New 21 Conan O’Brien Needs A Friend Stitcher Midroll 4 i3 22 Oprah’s SuperSoul Conversations Stitcher Midroll 4 i5 23 VIEWS with David Dobrik and Jason RADIO.COM/Cadence13 Cadence13 -

The Guide Your Connection to Spokane Public Radio Name(S) ______Volume 40 / No

Spokane Public Radio Membership and Donation Form Annual or additional contributions to Spokane Public Radio are always welcome. Mail to: Spokane Public Radio,1229 N. Monroe St., Spokane, WA 99201 THANK YOU FOR YOUR SUPPORT The Guide Your Connection to Spokane Public Radio Name(s) ___________________________________________________________________ Volume 40 / No. 2 April to June 2020 Address ___________________________________________________________________ SPR: The Information, News, & Entertainment Day Phone ( ) __________________ Evening Phone ( ) _____________________ You Need E-Mail ____________________________________________________________________ A note from Cary Boyce, President and General Manager Type of Gift/Pledge Dear Listeners, □ New membership □ Extra Gift □ Renewing Member □ Payment on Existing Pledge First, thank you for your ongoing support. These are unprecedented times Donation Amount $ ____________________________ in public radio as they are across the nation, and in our communities. At SPR we are doing our best to bring you news and information you can Payment Option rely on and use, in as timely a manner as possible. News from around the □ Sustaining Membership - ongoing monthly gift with automatic membership renewal nation, the state, and world—from NPR and BBC and our own reporters—is □ Credit/Debit card (see below) □ Auto Bill Pay from my bank brought to your cars and living rooms through SPR. It’s truly a great honor to Part of the NPR network □ Full payment enclosed □ First payment of $ ________________ enclosed work with such selfless and diligent colleagues here and around the world. The COVID-19 virus has changed the way SPR operates. Several staff □ Monthly: __________ months for $ ________________ per month □ EFT - for Sustaining monthly members are working from home as they can, even as others hold down the Pledge securely on-line: WA fort in our studios. -

Immigration Advocate Weighs in on Trump Administration's Move to End Flores Agreement

WAMU 88.5 BBC World Service NEWSCAST DONATE LIVE RADIO SHOWS NATIONAL Immigration Advocate Weighs In On Trump Administration's Move To End Flores Agreement LISTEN · 4:59 PLAYLIST Download Transcript August 21, 2019 · 5:19 PM ET Heard on All Things Considered NPR's Audie Cornish speaks with Wendy Young, president of the child advocacy organization KIND, about President Trump's moves to change requirements for the detention of migrant children. AUDIE CORNISH, HOST: The Trump administration is moving to allow the government to detain migrant families with children indefinitely. The Department of Homeland Security announced today that they plan to publish a new regulation that would eliminate the current 20- day limit on the detention of minors. That 20-day limit stems from a 1997 court settlement called the Flores Agreement that governs conditions for migrant children in federal care. Acting DHS Secretary Kevin McAleenan blamed the Flores Settlement for the influx of hundreds of thousands of migrants at the southern border. (SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING) KEVIN MCALEENAN: The driving factor for this crisis is weakness in our legal framework for immigration. Human smugglers advertise, and intending migrants know well that even if they cross the border illegally, arriving at our border with a child has meant that they will be released into the United States to wait for court proceedings that could take five years or more. CORNISH: The government is set to publish the final rule on Friday. It will require approval from a federal judge before can go into effect. We're joined now by Wendy Young. -

The Popular Culture Studies Journal

THE POPULAR CULTURE STUDIES JOURNAL VOLUME 6 NUMBER 1 2018 Editor NORMA JONES Liquid Flicks Media, Inc./IXMachine Managing Editor JULIA LARGENT McPherson College Assistant Editor GARRET L. CASTLEBERRY Mid-America Christian University Copy Editor Kevin Calcamp Queens University of Charlotte Reviews Editor MALYNNDA JOHNSON Indiana State University Assistant Reviews Editor JESSICA BENHAM University of Pittsburgh Please visit the PCSJ at: http://mpcaaca.org/the-popular-culture- studies-journal/ The Popular Culture Studies Journal is the official journal of the Midwest Popular and American Culture Association. Copyright © 2018 Midwest Popular and American Culture Association. All rights reserved. MPCA/ACA, 421 W. Huron St Unit 1304, Chicago, IL 60654 Cover credit: Cover Artwork: “Wrestling” by Brent Jones © 2018 Courtesy of https://openclipart.org EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD ANTHONY ADAH FALON DEIMLER Minnesota State University, Moorhead University of Wisconsin-Madison JESSICA AUSTIN HANNAH DODD Anglia Ruskin University The Ohio State University AARON BARLOW ASHLEY M. DONNELLY New York City College of Technology (CUNY) Ball State University Faculty Editor, Academe, the magazine of the AAUP JOSEF BENSON LEIGH H. EDWARDS University of Wisconsin Parkside Florida State University PAUL BOOTH VICTOR EVANS DePaul University Seattle University GARY BURNS JUSTIN GARCIA Northern Illinois University Millersville University KELLI S. BURNS ALEXANDRA GARNER University of South Florida Bowling Green State University ANNE M. CANAVAN MATTHEW HALE Salt Lake Community College Indiana University, Bloomington ERIN MAE CLARK NICOLE HAMMOND Saint Mary’s University of Minnesota University of California, Santa Cruz BRIAN COGAN ART HERBIG Molloy College Indiana University - Purdue University, Fort Wayne JARED JOHNSON ANDREW F. HERRMANN Thiel College East Tennessee State University JESSE KAVADLO MATTHEW NICOSIA Maryville University of St. -

PRACHTER: Hi, I'm Richard Prachter from the Miami Herald

Bob Garfield, author of “The Chaos Scenario” (Stielstra Publishing) Appearance at Miami Book Fair International 2009 PACHTER: Hi, I’m Richard Pachter from the Miami Herald. I’m the Business Books Columnist for Business Monday. I’m going to introduce Chris and Bob. Christopher Kenneally responsible for organizing and hosting programs at Copyright Clearance Center. He’s an award-winning journalist and author of Massachusetts 101: A History of the State, from Red Coats to Red Sox. He’s reported on education, business, travel, culture and technology for The New York Times, The Boston Globe, the LA Times, the Independent of London and other publications. His articles on blogging, search engines and the impact of technology on writers have appeared in the Boston Business Journal, Washington Business Journal and Book Tech Magazine, among other publications. He’s also host and moderator of the series Beyond the Book, which his frequently broadcast on C- SPAN’s Book TV and on Book Television in Canada. And Chris tells me that this panel is going to be part of a podcast in the future. So we can look forward to that. To Chris’s left is Bob Garfield. After I reviewed Bob Garfield’s terrific book, And Now a Few Words From Me, in 2003, I received an e-mail from him that said, among other things, I want to have your child. This was an interesting offer, but I’m married with three kids, and Bob isn’t quite my type, though I appreciated the opportunity and his enthusiasm. After all, Bob Garfield is a living legend. -

Freelance Journalist Invoice Washington Dc

Freelance Journalist Invoice Washington Dc Calfless and unbreathing Alasdair palsies her witenagemot beefburgers photosensitizes and droops longways. Zymotic and russety Herby manipulates almost theocratically, though Christ scats his mammet unknitted. Looted and emarginate Malcolm never outguess his geebung! What happened to understand what to freelance journalist, where she clerked for Exempts licensed pharmacists from the ABC test. English and psychology from Fairfield University in Connecticut. Doing yet she needed to out put Sherriff on my footing are the year ends. International in five native Toronto and later worked as a reporter and editor for UPI in Washington and Hong Kong; as a bureau chief in Manila and Nairobi; and as editor for Europe, Africa and the morning East based in London. This file is where big. This template for public service, from oil drilling in freelance journalist invoice washington dc public; and skilled trade on the invoice template yours, you may work? Vox free by all. He says its like some who attend are not there yet make a point, they are there a cause mayhem. President of Serbia and convicted war criminal, Slobodan Milosevic. Generate a template for target time. Endangered Species on and wildlife protections. As a freelance commercial writer, proofreader and editor, i practice your job easier freelance writing the company and eight more successful. Your visitors cannot display this state until the add a Google Maps API Key. Some cargo is easier to work than others. Verification is people working. The international radio news service period the BBC. Evan Sernoffsky is a reporter for the San Francisco Chronicle specializing in criminal intelligence, crime and breaking news. -

Edward R. Murrow

ABOUT AMERICA EDWARD R. MURROW JOURNALISM AT ITS BEST TABLE OF CONTENTS Edward R. Murrow: A Life.............................................................1 Freedom’s Watchdog: The Press in the U.S.....................................4 Murrow: Founder of American Broadcast Journalism....................7 Harnessing “New” Media for Quality Reporting .........................10 “See It Now”: Murrow vs. McCarthy ...........................................13 Murrow’s Legacy ..........................................................................16 Bibliography..................................................................................17 Photo Credits: University of Maryland; right, Digital Front cover: © CBS News Archive Collections and Archives, Tufts University. Page 1: CBS, Inc., AP/WWP. 12: Joe Barrentine, AP/WWP. 2: top left & right, Digital Collections and Archives, 13: Digital Collections and Archives, Tufts University; bottom, AP/WWP. Tufts University. 4: Louis Lanzano, AP/WWP. 14: top, Time Life Pictures/Getty Images; 5 : left, North Wind Picture Archives; bottom, AP/WWP. right, Tim Roske, AP/WWP. 7: Digital Collections and Archives, Tufts University. Executive Editor: George Clack 8: top left, U.S. Information Agency, AP/WWP; Managing Editor: Mildred Solá Neely right, AP/WWP; bottom left, Digital Collections Art Director/Design: Min-Chih Yao and Archives, Tufts University. Contributing editors: Chris Larson, 10: Digital Collections and Archives, Tufts Chandley McDonald University. Photo Research: Ann Monroe Jacobs 11: left, Library of American Broadcasting, Reference Specialist: Anita N. Green 1 EDWARD R. MURROW: A LIFE By MARK BETKA n a cool September evening somewhere Oin America in 1940, a family gathers around a vacuum- tube radio. As someone adjusts the tuning knob, a distinct and serious voice cuts through the airwaves: “This … is London.” And so begins a riveting first- hand account of the infamous “London Blitz,” the wholesale bombing of that city by the German air force in World War II. -

Podcast Directory of Influencers

The Ultimate Directory of Podcasters 670 OF THE WORLD’S LEADING PODCASTERS Who Can Make You Famous By Featuring YOU On Their High-Visibility Platforms Brought to you by & And Ken D Foster k Page 3 1. Have I already been a guest on other shows? 3. Do I have my own show, or a substantial online presence, and Let’s face it, you wouldn’t have wanted your first TV interview have I already connected with, featured, or had a podcaster on to be with Oprah during her prime, or your first radio interview my show? with Howard Stern during his. The podcasters featured within these pages are the true icons of the podcasting world. You When seeking to connect with podcasters, it is certainly easier have ONE shot to get it right. Mess it up and not only will to do so if you’re an influencer in your own right, have existing you never be invited back to their show, given that the world relationships with other podcasters and/or have a platform that of podcasters is tight, word will spread about your rivals theirs. Few, however, will meet one, let alone all three, of appearance and the odds of being invited onto others’ shows these criteria. There is, however, an easy solution. Rather than will be dramatically reduced. wait for someone to come to your door and ‘anoint’ you as being ready to get onto the influencer playing field, take matters into Recommendation: Cut your teeth on shows with significantly your own hands and start embodying the character traits, and less reach before reaching out for those featured in this replicating the actions, of influencers you admire. -

Newsletter 1

The Newsletter of the Dialogue: Oral History Section Volume 6, Issue 1 Winter 2010 Society of American Archivists FROM THE CHAIR Mark Cave, The Historic New Orleans Collection Our section meeting in Austin anniversary. She is planning for on-site interviews to was a great success. 100 people take place at the annual conference in Washington. enjoyed the live interview conducted by Jim Fogerty Thank you to those of you who replied to our query with David Gracy. Jim did a to the section membership in October. We received wonderful job in conducting the really helpful information related to the interests and interview, and it was such a great needs of the section membership. This information way to honor Mr. Gracy for his will be helpful in the creation of an online survey, contributions to our profession. which will be a part of our website, and continually Our next section meeting promises to be equally gather information about the section’s membership. engaging. It is being planned by Vice Chair/Chair Past Chair Al Stein along with Nominating Committee Elect Joel Minor and will be devoted to oral history members Doug Boyd and Herman Trojanowski will be and human rights. looking for candidates for Vice Chair and two Steering Committee members for our next election, and will Lauren Kata has been busy since the Austin meeting also be reviewing our current bylaws. developing our SAA 75th Anniversary Oral History Project. Lauren has been named as the section’s A special thanks to Jennifer Eidson for preparing this representative on the 75th Anniversary Task Force, issue of Dialogue and for maintaining the section’s which is coordinating all the events surrounding the website. -

NEA-Annual-Report-1980.Pdf

National Endowment for the Arts National Endowment for the Arts Washington, D.C. 20506 Dear Mr. President: I have the honor to submit to you the Annual Report of the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Council on the Arts for the Fiscal Year ended September 30, 1980. Respectfully, Livingston L. Biddle, Jr. Chairman The President The White House Washington, D.C. February 1981 Contents Chairman’s Statement 2 The Agency and Its Functions 4 National Council on the Arts 5 Programs 6 Deputy Chairman’s Statement 8 Dance 10 Design Arts 32 Expansion Arts 52 Folk Arts 88 Inter-Arts 104 Literature 118 Media Arts: Film/Radio/Television 140 Museum 168 Music 200 Opera-Musical Theater 238 Program Coordination 252 Theater 256 Visual Arts 276 Policy and Planning 316 Deputy Chairman’s Statement 318 Challenge Grants 320 Endowment Fellows 331 Research 334 Special Constituencies 338 Office for Partnership 344 Artists in Education 346 Partnership Coordination 352 State Programs 358 Financial Summary 365 History of Authorizations and Appropriations 366 Chairman’s Statement The Dream... The Reality "The arts have a central, fundamental impor In the 15 years since 1965, the arts have begun tance to our daily lives." When those phrases to flourish all across our country, as the were presented to the Congress in 1963--the illustrations on the accompanying pages make year I came to Washington to work for Senator clear. In all of this the National Endowment Claiborne Pell and began preparing legislation serves as a vital catalyst, with states and to establish a federal arts program--they were communities, with great numbers of philanthro far more rhetorical than expressive of a national pic sources.