OPERATIONAL AMPLIFIERS: Basic Circuits and Applications

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 2 Basic Concepts in RF Design

Chapter 2 Basic Concepts in RF Design 1 Sections to be covered • 2.1 General Considerations • 2.2 Effects of Nonlinearity • 2.3 Noise • 2.4 Sensitivity and Dynamic Range • 2.5 Passive Impedance Transformation 2 Chapter Outline Nonlinearity Noise Impedance Harmonic Distortion Transformation Compression Noise Spectrum Intermodulation Device Noise Series-Parallel Noise in Circuits Conversion Matching Networks 3 The Big Picture: Generic RF Transceiver Overall transceiver Signals are upconverted/downconverted at TX/RX, by an oscillator controlled by a Frequency Synthesizer. 4 General Considerations: Units in RF Design Voltage gain: rms value Power gain: These two quantities are equal (in dB) only if the input and output impedance are equal. Example: an amplifier having an input resistance of R0 (e.g., 50 Ω) and driving a load resistance of R0 : 5 where Vout and Vin are rms value. General Considerations: Units in RF Design “dBm” The absolute signal levels are often expressed in dBm (not in watts or volts); Used for power quantities, the unit dBm refers to “dB’s above 1mW”. To express the signal power, Psig, in dBm, we write 6 Example of Units in RF An amplifier senses a sinusoidal signal and delivers a power of 0 dBm to a load resistance of 50 Ω. Determine the peak-to-peak voltage swing across the load. Solution: a sinusoid signal having a peak-to-peak amplitude of Vpp an rms value of Vpp/(2√2), 0dBm is equivalent to 1mW, where RL= 50 Ω thus, 7 Example of Units in RF A GSM receiver senses a narrowband (modulated) signal having a level of -100 dBm. -

The Basics of Power the Background of Some of the Electronics

We Often talk abOut systeMs from a “in front of the (working) screen” or a Rudi van Drunen “software” perspective. Behind all this there is a complex hardware architecture that makes things work. This is your machine: the machine room, the network, and all. Everything has to do with electronics and electrical signals. In this article I will discuss the basics of power the background of some of the electronics, Rudi van Drunen is a senior UNIX systems consul- introducing the basics of power and how tant with Competa IT B.V. in the Netherlands. He to work with it, so that you will be able to also has his own consulting company, Xlexit Tech- nology, doing low-level hardware-oriented jobs. understand the issues and calculations that [email protected] are the basis of delivering the electrical power that makes your system work. There are some basic things that drive the electrons through your machine. I will be explaining Ohm’s law, the power law, and some aspects that will show you how to lay out your power grid. power Law Any piece of equipment connected to a power source will cause a current to flow. The current will then have the device perform its actions (and produce heat). To calculate the current that will be flowing through the machine (or light bulb) we divide the power rating (in watts) by the voltage (in volts) to which the system is connected. An ex- ample here is if you take a 100-watt light bulb and connect this light bulb to the wall power voltage of 115 volts, the resulting current will be 100/115 = 0.87 amperes. -

1.5A, 24V, 17Mhz Power Operational Amplifier Datasheet (Rev. E)

OPA564 www.ti.com SBOS372E –OCTOBER 2008–REVISED JANUARY 2011 1.5A, 24V, 17MHz POWER OPERATIONAL AMPLIFIER Check for Samples: OPA564 1FEATURES 23• HIGH OUTPUT CURRENT: 1.5A DESCRIPTION • WIDE POWER-SUPPLY RANGE: The OPA564 is a low-cost, high-current operational – Single Supply: +7V to +24V amplifier that is ideal for driving up to 1.5A into reactive loads. The high slew rate provides 1.3MHz – Dual Supply: ±3.5V to ±12V full-power bandwidth and excellent linearity. These • LARGE OUTPUT SWING: 20VPP at 1.5A monolithic integrated circuits provide high reliability in • FULLY PROTECTED: demanding powerline communications and motor control applications. – THERMAL SHUTDOWN – ADJUSTABLE CURRENT LIMIT The OPA564 operates from a single supply of 7V to 24V, or dual power supplies of ±3.5V to ±12V. In • DIAGNOSTIC FLAGS: single-supply operation, the input common-mode – OVER-CURRENT range extends to the negative supply. At maximum – THERMAL SHUTDOWN output current, a wide output swing provides a 20VPP (I = 1.5A) capability with a nominal 24V supply. • OUTPUT ENABLE/SHUTDOWN CONTROL OUT • HIGH SPEED: The OPA564 is internally protected against over-temperature conditions and current overloads. It – GAIN-BANDWIDTH PRODUCT: 17MHz is designed to provide an accurate, user-selected – FULL-POWER BANDWIDTH AT 10VPP: current limit. Two flag outputs are provided; one 1.3MHz indicates current limit and the second shows a – SLEW RATE: 40V/ms thermal over-temperature condition. It also has an Enable/Shutdown pin that can be forced low to shut • DIODE FOR JUNCTION TEMPERATURE down the output, effectively disconnecting the load. MONITORING The OPA564 is housed in a thermally-enhanced, • HSOP-20 PowerPAD™ PACKAGE surface-mount PowerPAD™ package (HSOP-20) with (Bottom- and Top-Side Thermal Pad Versions) the choice of the thermal pad on either the top side or the bottom side of the package. -

Designing Linear Amplifiers Using the IL300 Optocoupler Application Note

Application Note 50 Vishay Semiconductors Designing Linear Amplifiers Using the IL300 Optocoupler INTRODUCTION linearizes the LED’s output flux and eliminates the LED’s This application note presents isolation amplifier circuit time and temperature. The galvanic isolation between the designs useful in industrial, instrumentation, medical, and input and the output is provided by a second PIN photodiode communication systems. It covers the IL300’s coupling (pins 5, 6) located on the output side of the coupler. The specifications, and circuit topologies for photovoltaic and output current, IP2, from this photodiode accurately tracks the photoconductive amplifier design. Specific designs include photocurrent generated by the servo photodiode. unipolar and bipolar responding amplifiers. Both single Figure 1 shows the package footprint and electrical ended and differential amplifier configurations are discussed. schematic of the IL300. The following sections discuss the Also included is a brief tutorial on the operation of key operating characteristics of the IL300. The IL300 photodetectors and their characteristics. performance characteristics are specified with the Galvanic isolation is desirable and often essential in many photodiodes operating in the photoconductive mode. measurement systems. Applications requiring galvanic isolation include industrial sensors, medical transducers, and IL300 mains powered switchmode power supplies. Operator safety 1 8 and signal quality are insured with isolated interconnections. These isolated interconnections commonly use isolation 2 K2 7 amplifiers. K1 Industrial sensors include thermocouples, strain gauges, and pressure transducers. They provide monitoring signals to a 3 6 process control system. Their low level DC and AC signal must be accurately measured in the presence of high 4 5 common-mode noise. -

NTE7144 Integrated Circuit BIMOS Operational Amplifier W/MOSFET Input, Bipolar Output

NTE7144 Integrated Circuit BIMOS Operational Amplifier w/MOSFET Input, Bipolar Output Description: The NTE7144 is an integrated circuit operational amplifier in an 8–Lead Mini–DIP type package that combines the advantages of high–voltage PMOS transistors with high–voltage bipolar transistors on a single monolithic chip. This device features gate–protected MOSFET (PMOS) transistors in the in- put circuit to provide very–high–input impedance, very–low–input current, and high–speed perfor- mance. The NTE7144 operates at supply voltages from 4V to 36V (either single or dual supply) and is internally phase–compensated to achieve stable operation in unity–gain follower operation. The use of PMOS field–effect transistors in the input stage results in common–mode input–voltage capability down to 0.5V below the negative–supply terminal, an important attribute for single–supply applications. The output stage uses bipolar transistors and includes built–in protection against dam- age from load–terminal short–circuiting to either supply–rail or to GND. Features: D MOSFET Input Stage: Very High Input Impedance Very Low Input Current Wide Common–Mode Input Voltage Range Output Swing Complements Input Common–Mode Range D Directly Replaces Industry Type 741 in Most Applications Applications: D Ground–Referenced Single–Supply Amplifiers in Automobile and Portable Instrumentation D Sample and Hold Amplifiers D Long–Duration Timers/Multivibrators (Microseconds – Minutes – Hours) D Photocurrent Instrumentation D Peak Detectors D Active Filters D Comparators D Interface in 5V TTL Systems and other Low–Supply Voltage Systems D All Standard Operational Amplifier Applications D Function Generators D Tone Controls D Power Supplies D Portable Instruments D Intrusion Alarm Systems Absolute Maximum Ratings: DC Supply Voltage (Between V+ and V– Terminals). -

Example of a MOSFET Operational Amplifier

Example of a MOSFET Operational Amplifier: This circuit is one I “designed” as an example for Engineering 1620. It is certainly not fully optimized and I am not sure it is free of errors. It is based on a 1.5 micron, P-well process and therefore uses an N-channel differential pair for its input. This is somewhat unusual because P-channel devices have lower intrinsic noise and are the device-type of choice for the input stage. I did this simply to avoid doing your SPICE assignment for you. The overall properties of the circuit are given in the table below. Amplifier Property Value A0 – DC Gain 86 DB (X20,000) fp – dominant pole position 400 Hz fGBW 8.0 MHz fU – unity gain frequency 5.6 MHz Output stage resistance at low frequency 277 K Zero position 10.7 MHz Slew Rate 710 6 V/sec Output stage quiescent current 65 a Opamp quiescent current 103 a Bias circuit quiescent current 104 a Total system quiescent current 210 a VDD 5.0 volts Total system power 1.1 mW MOSFET Operational Amplifier Gain and Phase 10 0 18 0 80 12 0 60 Gain 60 Phase 40 0 Gain (DB) 20 -60 Phase (deg.) 0 -120 -20 -180 1.00E+02 1.00E+03 1.00E+04 1.00E+05 1.00E+06 1.00E+07 1.00E+08 Frequency (Hz) Phase margin = 60 deg. Parameter Table for MOSFET Opamp Example element model vds vgs vth vov id gm ro m1 nssb 0.748 0.851 0.547 0.304 3.77E-05 2.90E-04 5.54E+05 m10 nssb 3.368 0.851 0.547 0.304 4.12E-05 3.11E-04 8.09E+05 m12 nssb 0.711 0.711 0.546 0.165 3.51E-05 5.01E-04 5.05E+05 m13 nssb 0.838 0.851 0.547 0.304 3.79E-05 2.91E-04 5.92E+05 m14 nssb 3.078 1.079 0.840 0.239 3.51E-05 -

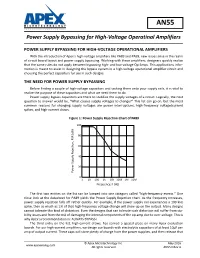

AN55 Power Supply Bypassing for High-Voltage Operational Amplifiers

AN55 Power Supply Bypassing for High-Voltage Operatinal Amplifiers POWER SUPPLY BYPASSING FOR HIGH-VOLTAGE OPERATIONAL AMPLIFIERS With the introduction of Apex’s high-voltage amplifiers like PA89 and PA99, new issues arise in the realm of circuit board layout and power supply bypassing. Working with these amplifiers, designers quickly realize that the same rules do not apply between bypassing high- and low-voltage Op-Amps. This applications infor- mation is meant to assist in designing the bypass system in a high-voltage operational amplifier circuit and choosing the perfect capacitors for use in such designs. THE NEED FOR POWER SUPPLY BYPASSING Before finding a couple of high-voltage capacitors and tacking them onto your supply rails, it is vital to realize the purpose of these capacitors and what we need them to do. Power supply bypass capacitors are there to stabilize the supply voltages of a circuit. Logically, the next question to answer would be, “What causes supply voltages to change?” This list can go on, but the most common reasons for changing supply voltages are power interruptions, high-frequency voltage/current spikes, and high-current draws. Figure 1: Power Supply Rejection Chart of PA89 100 80 60 40 20 WŽǁĞƌ^ƵƉƉůLJZĞũĞĐƟŽŶ͕W^Z;ĚͿ 0 1 10100 1k 10k 100k1M 10M Frequency, F (Hz) The first two entries on the list can be lumped into one category called “high-frequency events.” One close look at the datasheet for PA89 yields the Power Supply Rejection chart. As the frequency increases, power supply rejection falls off rather quickly. For example, if the power supply rail experiences a 100 kHz spike, then as much as 1% of that high-frequency voltage change will show up on the output. -

A Differential Operational Amplifier Circuit Collection

Application Report SLOA064A – April 2003 A Differential Op-Amp Circuit Collection Bruce Carter High Performance Linear Products ABSTRACT All op-amps are differential input devices. Designers are accustomed to working with these inputs and connecting each to the proper potential. What happens when there are two outputs? How does a designer connect the second output? How are gain stages and filters developed? This application note answers these questions and gives a jumpstart to apprehensive designers. 1 INTRODUCTION The idea of fully-differential op-amps is not new. The first commercial op-amp, the K2-W, utilized two dual section tubes (4 active circuit elements) to implement an op-amp with differential inputs and outputs. It required a ±300 Vdc power supply, dissipating 4.5 W of power, had a corner frequency of 1 Hz, and a gain bandwidth product of 1 MHz(1). In an era of discrete tube or transistor op-amp modules, any potential advantage to be gained from fully-differential circuitry was masked by primitive op-amp module performance. Fully- differential output op-amps were abandoned in favor of single ended op-amps. Fully-differential op-amps were all but forgotten, even when IC technology was developed. The main reason appears to be the simplicity of using single ended op-amps. The number of passive components required to support a fully-differential circuit is approximately double that of a single-ended circuit. The thinking may have been “Why double the number of passive components when there is nothing to be gained?” Almost 50 years later, IC processing has matured to the point that fully-differential op-amps are possible that offer significant advantage over their single-ended cousins. -

9 Op-Amps and Transistors

Notes for course EE1.1 Circuit Analysis 2004-05 TOPIC 9 – OPERATIONAL AMPLIFIER AND TRANSISTOR CIRCUITS . Op-amp basic concepts and sub-circuits . Practical aspects of op-amps; feedback and stability . Nodal analysis of op-amp circuits . Transistor models . Frequency response of op-amp and transistor circuits 1 THE OPERATIONAL AMPLIFIER: BASIC CONCEPTS AND SUB-CIRCUITS 1.1 General The operational amplifier is a universal active element It is cheap and small and easier to use than transistors It usually takes the form of an integrated circuit containing about 50 – 100 transistors; the circuit is designed to approximate an ideal controlled source; for many situations, its characteristics can be considered as ideal It is common practice to shorten the term "operational amplifier" to op-amp The term operational arose because, before the era of digital computers, such amplifiers were used in analog computers to perform the operations of scalar multiplication, sign inversion, summation, integration and differentiation for the solution of differential equations Nowadays, they are considered to be general active elements for analogue circuit design and have many different applications 1.2 Op-amp Definition We may define the op-amp to be a grounded VCVS with a voltage gain (µ) that is infinite The circuit symbol for the op-amp is as follows: An equivalent circuit, in the form of a VCVS is as follows: The three terminal voltages v+, v–, and vo are all node voltages relative to ground When we analyze a circuit containing op-amps, we cannot use the -

Current Source & Source Transformation Notes

EE301 – CURRENT SOURCES / SOURCE CONVERSION Learning Objectives a. Analyze a circuit consisting of a current source, voltage source and resistors b. Convert a current source and a resister into an equivalent circuit consisting of a voltage source and a resistor c. Evaluate a circuit that contains several current sources in parallel Ideal sources An ideal source is an active element that provides a specified voltage or current that is completely independent of other circuit elements. DC Voltage DC Current Source Source Constant Current Sources The voltage across the current source (Vs) is dependent on how other components are connected to it. Additionally, the current source voltage polarity does not have to follow the current source’s arrow! 1 Example: Determine VS in the circuit shown below. Solution: 2 Example: Determine VS in the circuit shown above, but with R2 replaced by a 6 k resistor. Solution: 1 8/31/2016 EE301 – CURRENT SOURCES / SOURCE CONVERSION 3 Example: Determine I1 and I2 in the circuit shown below. Solution: 4 Example: Determine I1 and VS in the circuit shown below. Solution: Practical voltage sources A real or practical source supplies its rated voltage when its terminals are not connected to a load (open- circuited) but its voltage drops off as the current it supplies increases. We can model a practical voltage source using an ideal source Vs in series with an internal resistance Rs. Practical current source A practical current source supplies its rated current when its terminals are short-circuited but its current drops off as the load resistance increases. We can model a practical current source using an ideal current source in parallel with an internal resistance Rs. -

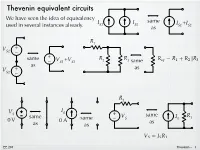

Thevenin Equivalent Circuits

Thevenin equivalent circuits We have seen the idea of equivalency same IS1 IS2 I +I used in several instances already. as S1 S2 R1 V + S1 – + same V +V R R = + – S1 S2 2 3 same as V + as S2 – R1 V IS S + V same R same same – S IS 1 0 V 0 A as as as = EE 201 Thevenin – 1 The behavior of any circuit, with respect to a pair of terminals (port) can be represented with a Thevenin equivalent, which consists of a voltage source in series with a resistor. load some two terminals some + R v circuit (two nodes) = circuit L RL port – RTh RTh load + + Thevenin + V V R v Th – equivalent Th – L RL – Need to determine VTh and RTh so that the model behaves just like the original. EE 201 Thevenin – 2 Norton equivalent load load some + + I v circuit vRL N RN RL – – Ideas developed independently (Thevenin in 1880’s and Norton in 1920’s). But we recognize the two forms as identical because they are source transformations of each other. In EE 201, we won’t make a distinction between the methods for finding Thevenin and Norton. Find one and we have the other. RTh = + V IN R Th – N = EE 201 Thevenin – 3 Example R 1.5 k! 1 RTh 1 k! V R I R R S + 2 S L V + L 9V – 3 k! 6 mA Th – 12 V Attach various load resistors to the R v i P original circuit. Do the same for 1 ! 11.99 mV 11.99 mA 0.144 mW the equivalent circuit. -

IR Temperature Sensor

IR Temperature Sensor By Kika Arias & Elaine Ng MIT 6.101 Final Project Spring 2020 1 Introduction (Kika) The goal of our project is to build an infrared thermometer which is a device that is used to measure the emitted energy from the surface of an object. IR thermometers are used in medical, industrial and home settings for a wide variety of applications. Many electronics retailers sell IR thermometer sensors that perform all of the processing to produce a temperature reading. We wanted to dissect this “black box” to understand how waves of energy can become a human readable temperature. We learned that IR thermometers consist of three basic stages. A sensing stage, in which IR radiation is converted to an electrical signal, a signal conditioning stage, where filtering, amplification, and linearization are performed, and a digital output stage, where the analog signal is converted into a digital one. Our project replicates these basic stages to create a simulated IR temperature sensor. System Overview (Kika) Fig 1. System Block Diagram. Thermopile signal processing in red, and temperature calculation and digital output in purple. As mentioned in the previous section, an IR thermometer consists of three basic stages: sensing, signal conditioning, and digital output. Figure 1 shows our system block diagram with the sensing and signal conditioning stages shown in red, and the digital output and additional processing shown in purple. The sensing stage of our project uses a thermopile sensor which has a negative temperature coefficient (NTC) thermistor for temperature compensation. The thermopile sensor absorbs infrared radiation and converts the IR to a small voltage (typically on the order of μVs).