IR Temperature Sensor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 2 Basic Concepts in RF Design

Chapter 2 Basic Concepts in RF Design 1 Sections to be covered • 2.1 General Considerations • 2.2 Effects of Nonlinearity • 2.3 Noise • 2.4 Sensitivity and Dynamic Range • 2.5 Passive Impedance Transformation 2 Chapter Outline Nonlinearity Noise Impedance Harmonic Distortion Transformation Compression Noise Spectrum Intermodulation Device Noise Series-Parallel Noise in Circuits Conversion Matching Networks 3 The Big Picture: Generic RF Transceiver Overall transceiver Signals are upconverted/downconverted at TX/RX, by an oscillator controlled by a Frequency Synthesizer. 4 General Considerations: Units in RF Design Voltage gain: rms value Power gain: These two quantities are equal (in dB) only if the input and output impedance are equal. Example: an amplifier having an input resistance of R0 (e.g., 50 Ω) and driving a load resistance of R0 : 5 where Vout and Vin are rms value. General Considerations: Units in RF Design “dBm” The absolute signal levels are often expressed in dBm (not in watts or volts); Used for power quantities, the unit dBm refers to “dB’s above 1mW”. To express the signal power, Psig, in dBm, we write 6 Example of Units in RF An amplifier senses a sinusoidal signal and delivers a power of 0 dBm to a load resistance of 50 Ω. Determine the peak-to-peak voltage swing across the load. Solution: a sinusoid signal having a peak-to-peak amplitude of Vpp an rms value of Vpp/(2√2), 0dBm is equivalent to 1mW, where RL= 50 Ω thus, 7 Example of Units in RF A GSM receiver senses a narrowband (modulated) signal having a level of -100 dBm. -

The Basics of Power the Background of Some of the Electronics

We Often talk abOut systeMs from a “in front of the (working) screen” or a Rudi van Drunen “software” perspective. Behind all this there is a complex hardware architecture that makes things work. This is your machine: the machine room, the network, and all. Everything has to do with electronics and electrical signals. In this article I will discuss the basics of power the background of some of the electronics, Rudi van Drunen is a senior UNIX systems consul- introducing the basics of power and how tant with Competa IT B.V. in the Netherlands. He to work with it, so that you will be able to also has his own consulting company, Xlexit Tech- nology, doing low-level hardware-oriented jobs. understand the issues and calculations that [email protected] are the basis of delivering the electrical power that makes your system work. There are some basic things that drive the electrons through your machine. I will be explaining Ohm’s law, the power law, and some aspects that will show you how to lay out your power grid. power Law Any piece of equipment connected to a power source will cause a current to flow. The current will then have the device perform its actions (and produce heat). To calculate the current that will be flowing through the machine (or light bulb) we divide the power rating (in watts) by the voltage (in volts) to which the system is connected. An ex- ample here is if you take a 100-watt light bulb and connect this light bulb to the wall power voltage of 115 volts, the resulting current will be 100/115 = 0.87 amperes. -

Current Source & Source Transformation Notes

EE301 – CURRENT SOURCES / SOURCE CONVERSION Learning Objectives a. Analyze a circuit consisting of a current source, voltage source and resistors b. Convert a current source and a resister into an equivalent circuit consisting of a voltage source and a resistor c. Evaluate a circuit that contains several current sources in parallel Ideal sources An ideal source is an active element that provides a specified voltage or current that is completely independent of other circuit elements. DC Voltage DC Current Source Source Constant Current Sources The voltage across the current source (Vs) is dependent on how other components are connected to it. Additionally, the current source voltage polarity does not have to follow the current source’s arrow! 1 Example: Determine VS in the circuit shown below. Solution: 2 Example: Determine VS in the circuit shown above, but with R2 replaced by a 6 k resistor. Solution: 1 8/31/2016 EE301 – CURRENT SOURCES / SOURCE CONVERSION 3 Example: Determine I1 and I2 in the circuit shown below. Solution: 4 Example: Determine I1 and VS in the circuit shown below. Solution: Practical voltage sources A real or practical source supplies its rated voltage when its terminals are not connected to a load (open- circuited) but its voltage drops off as the current it supplies increases. We can model a practical voltage source using an ideal source Vs in series with an internal resistance Rs. Practical current source A practical current source supplies its rated current when its terminals are short-circuited but its current drops off as the load resistance increases. We can model a practical current source using an ideal current source in parallel with an internal resistance Rs. -

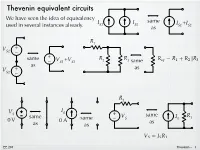

Thevenin Equivalent Circuits

Thevenin equivalent circuits We have seen the idea of equivalency same IS1 IS2 I +I used in several instances already. as S1 S2 R1 V + S1 – + same V +V R R = + – S1 S2 2 3 same as V + as S2 – R1 V IS S + V same R same same – S IS 1 0 V 0 A as as as = EE 201 Thevenin – 1 The behavior of any circuit, with respect to a pair of terminals (port) can be represented with a Thevenin equivalent, which consists of a voltage source in series with a resistor. load some two terminals some + R v circuit (two nodes) = circuit L RL port – RTh RTh load + + Thevenin + V V R v Th – equivalent Th – L RL – Need to determine VTh and RTh so that the model behaves just like the original. EE 201 Thevenin – 2 Norton equivalent load load some + + I v circuit vRL N RN RL – – Ideas developed independently (Thevenin in 1880’s and Norton in 1920’s). But we recognize the two forms as identical because they are source transformations of each other. In EE 201, we won’t make a distinction between the methods for finding Thevenin and Norton. Find one and we have the other. RTh = + V IN R Th – N = EE 201 Thevenin – 3 Example R 1.5 k! 1 RTh 1 k! V R I R R S + 2 S L V + L 9V – 3 k! 6 mA Th – 12 V Attach various load resistors to the R v i P original circuit. Do the same for 1 ! 11.99 mV 11.99 mA 0.144 mW the equivalent circuit. -

Chapter 2: Circuit Elements

Chapter 2: Circuit Elements Objectives o Understand concept of basic circuit elements . Resistor, voltage source, current source, capacitor, inductor o Learn to apply KVL, KCL, Ohm’s Law . Sign conventions Homework/Quiz/Exam Prep o When do we have enough equations? o Math requirements . Simultaneous linear algebraic equations Presentation o Ideal Basic Circuit Elements . Sources: Dependent and Independent . R, L, C o Resistors . Ohm’s Law . Power o Flashlight Circuit . KVL, KCL, Ohm . KVL shortcut o Special Cases . Short circuit; Open circuit . What happens to resistors that are shorted/opened? Activity: worksheet on KVL, KCL, Ohm Activity: sample problems Chapter 2: Circuit Elements There are five Ideal Basic Circuit Elements. We listed these in the previous chapter; we discuss them further here. The Ideal Basic Circuit Elements are as follows. Voltage source Current source Resistor Capacitor Inductor These circuit elements are used to model electrical systems, as we discussed in Chapter 1. They are available in the laboratory, but the ones in the lab are not “ideal”; they are “real”. When we draw circuit models on the board or in quizzes and exams, we assume that ideal elements are intended, unless otherwise stated. To solve circuits involving capacitors and inductors, we require differential equations. Therefore we will postpone these circuit elements until later in the course and deal for the moment with sources and resistors only. 2.1 Sources Source: a device capable of conversion between non-electrical energy and electrical energy. Examples… Generator: mechanical electrical Motor: electrical mechanical Important: energy and power can be either delivered or absorbed, depending on the circuit element and how it is connected into the circuit. -

Electrical Engineering Dictionary

ratio of the power per unit solid angle scat- tered in a specific direction of the power unit area in a plane wave incident on the scatterer R from a specified direction. RADHAZ radiation hazards to personnel as defined in ANSI/C95.1-1991 IEEE Stan- RS commonly used symbol for source dard Safety Levels with Respect to Human impedance. Exposure to Radio Frequency Electromag- netic Fields, 3 kHz to 300 GHz. RT commonly used symbol for transfor- mation ratio. radial basis function network a fully R-ALOHA See reservation ALOHA. connected feedforward network with a sin- gle hidden layer of neurons each of which RL Typical symbol for load resistance. computes a nonlinear decreasing function of the distance between its received input and Rabi frequency the characteristic cou- a “center point.” This function is generally pling strength between a near-resonant elec- bell-shaped and has a different center point tromagnetic field and two states of a quan- for each neuron. The center points and the tum mechanical system. For example, the widths of the bell shapes are learned from Rabi frequency of an electric dipole allowed training data. The input weights usually have transition is equal to µE/hbar, where µ is the fixed values and may be prescribed on the electric dipole moment and E is the maxi- basis of prior knowledge. The outputs have mum electric field amplitude. In a strongly linear characteristics, and their weights are driven 2-level system, the Rabi frequency is computed during training. equal to the rate at which population oscil- lates between the ground and excited states. -

AC Theory, Circuits, Generators & Motors

AC Theory, Circuits, Generators & Motors Course# EE603 ©EZpdh.com All Rights Reserved DOE-HDBK-1011/3-92 JUNE 1992 DOE FUNDAMENTALS HANDBOOK ELECTRICAL SCIENCE Volume 3 of 4 U.S. Department of Energy FSC-6910 Washington, D.C. 20585 Distribution Statement A. Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. This document has been reproduced directly from the best available copy. Available to DOE and DOE contractors from the Office of Scientific and Technical Information. P. O. Box 62, Oak Ridge, TN 37831; prices available from (615) 576- 8401. Available to the public from the National Technical Information Service, U.S. Department of Commerce, 5285 Port Royal Rd., Springfield, VA 22161. Order No. DE92019787 ELECTRICAL SCIENCE ABSTRACT The Electrical Science Fundamentals Handbook was developed to assist nuclear facility operating contractors provide operators, maintenance personnel, and the technical staff with the necessary fundamentals training to ensure a basic understanding of electrical theory, terminology, and application. The handbook includes information on alternating current (AC) and direct current (DC) theory, circuits, motors, and generators; AC power and reactive components; batteries; AC and DC voltage regulators; transformers; and electrical test instruments and measuring devices. This information will provide personnel with a foundation for understanding the basic operation of various types of DOE nuclear facility electrical equipment. Key Words: Training Material, Magnetism, DC Theory, DC Circuits, Batteries, DC Generators, -

Introduction to the Op Amp Outline Basic Concept What About Other

Outline Introduction to the Op Amp 1 Voltage Amplifiers Phyllis R. Nelson 2 Operational amplifier Cal Poly Pomona 3 Ideal op amp ECE 207 - Winter 2015 4 Applications of the ideal op amp model Phyllis R. Nelson (Cal Poly Pomona) Introduction to the Op Amp ECE 207 - Winter 2015 1 / 22 Phyllis R. Nelson (Cal Poly Pomona) Introduction to the Op Amp ECE 207 - Winter 2015 2 / 22 Basic concept What about other dependent sources? Voltage-controlled current source Amplify: increase, magnify, intensify measures the voltage vd between two nodes outputs a current Gvd What circuit elements from ECE 109 can amplify? Voltage-controlled voltage source RS Output power: measures the voltage between two nodes 2 + Po = (Avd) RL Is outputs that voltage times a gain V + v Av R Input power: S − d d L Pi = vdIS - Current-controlled current source measures a branch current outputs that current times a gain vd = ? IS = ? Phyllis R. Nelson (Cal Poly Pomona) Introduction to the Op Amp ECE 207 - Winter 2015 3 / 22 Phyllis R. Nelson (Cal Poly Pomona) Introduction to the Op Amp ECE 207 - Winter 2015 4 / 22 Measuring voltages Back to the example . RS Imeter R1 + Is + 2 I I2 = Is Imeter V v R Av R P = (Av ) R s − S − d i d L o d L V + R I s − 2 2 V = R I = R I R2 2 2 6 2 s - Ri VS vd = VS = VS if Ri RS If Imeter = 0, the measurement changes the voltage! Ri + Rs 1 + RS ' 6 Ri VS The circuit that measures a voltage (a voltmeter) IS = 0 as Ri Pi = vdIS 0 as Ri Ri + Rs → → ∞ → → ∞ is connected between two nodes (in parallel) needs to have an internal resistance large compared to the equivalent This circuit delivers power to the load while drawing very little power from resistance of the circuit it is measuring the source. -

EE-2049 Measurements & Circuits

LABORATORY MANUAL ELECTRICAL MEASUREMENTS and Circuits EE 2049 Khosrow Rad 2016 DEPARTMENT OF ELECTRICAL & COMPUTER ENGINEERING CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, LOS ANGELES 1 Published July 13, 2016 CONTENTS Experiment Title Page 1 Digital Multimeter Resistance Measurement 3 2 Digital Multimeter: DC Voltage and DC Current Measurement 5 3 Voltage Regulation and AC Power Supply 7 4 Function Generator and Oscilloscope 9 5 Oscilloscope Operation 12 6 PSpice Analysis of DC Circuits 15 7 Basic Circuit and Divider Rules 18 8 Kirchhof's Voltage Law and Kirchhof's Current Law 20 9 Divider rules for voltage (VDR) and current (CDR). 23 10 Mesh & Nodal Analysis 26 11 Thévenin’s Theorem 29 12 PSpice: Time Domain Analysis 33 13 The Response of an RC Circuit 39 14 The Response of an RL Circuit 42 15 Series Resonant Circuit 46 16 The Complete Response of 2nd Order RLC Circuits 49 2 Digital Multimeter Resistance Measurement EXPERIMENT 1 Here is the resistor color code: Color First Stripe Second Stripe Third Stripe Fourth Stripe Black 0 0 x1 Brown 1 1 x10 Red 2 2 x100 Orange 3 3 x1,000 Yellow 4 4 x10,000 Green 5 5 x100,000 Blue 6 6 x1,000,000 Purple 7 7 Gray 8 8 White 9 9 Gold 5% Silver 10% None 20% If the following color comes in third stripe it will act as Gold = * decimal multiplier =10-1 = 0.1 tolerance Silver = * decimal multiplier =10-2 = 0.01 tolerance No color = * decimal multiplier = * tolerance 1. Obtain about 15 resistors of the 15 KΩ value. Measure the resistance of each resistor using the DMM range that will give the maximum number of significant figures. -

Basic Electrical & DC Theory

Basic Electrical & DC Theory Course# EE601 ©EZpdh.com All Rights Reserved DOE-HDBK-1011/1-92 JUNE 1992 DOE FUNDAMENTALS HANDBOOK ELECTRICAL SCIENCE Volume 1 of 4 U.S. Department of Energy FSC-6910 Washington, D.C. 20585 Distribution Statement A. Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. This document has been reproduced directly from the best available copy. Available to DOE and DOE contractors from the Office of Scientific and Technical Information. P. O. Box 62, Oak Ridge, TN 37831; (615) 576-8401. Available to the public from the National Technical Information Service, U.S. Department of Commerce, 5285 Port Royal Rd., Springfield, VA 22161. Order No. DE92019785 ELECTRICAL SCIENCE ABSTRACT The Electrical Science Fundamentals Handbook was developed to assist nuclear facility operating contractors provide operators, maintenance personnel, and the technical staff with the necessary fundamentals training to ensure a basic understanding of electrical theory, terminology, and application. The handbook includes information on alternating current (AC) and direct current (DC) theory, circuits, motors, and generators; AC power and reactive components; batteries; AC and DC voltage regulators; transformers; and electrical test instruments and measuring devices. This information will provide personnel with a foundation for understanding the basic operation of various types of DOE nuclear facility electrical equipment. Key Words: Training Material, Magnetism, DC Theory, DC Circuits, Batteries, DC Generators, DC Motors, AC Theory, AC Power, AC Generators, Voltage Regulators, AC Motors, Transformers, Test Instruments, Electrical Distribution Rev. 0 ES ELECTRICAL SCIENCE FOREWORD The Department of Energy (DOE) Fundamentals Handbooks consist of ten academic subjects, which include Mathematics; Classical Physics; Thermodynamics, Heat Transfer, and Fluid Flow; Instrumentation and Control; Electrical Science; Material Science; Mechanical Science; Chemistry; Engineering Symbology, Prints, and Drawings; and Nuclear Physics and Reactor Theory. -

OPERATIONAL AMPLIFIERS: Basic Circuits and Applications

OPERATIONAL AMPLIFIERS: Basic Circuits and Applications ECEN – 457 (ESS) Edgar Sanchez-Sinencio, Texas A & M University ELEN 457 Outline of the course • Introduction & Motivation OP Amp Fundamentals • Circuits with Resistive Feedback • Basic Operators: Differential, Integrator, Low Pass • Filters • Static Op Amp Limitations • Dynamic Op Amp Limitations • Noise • Nonlinear Circuits • Signal Generators • Voltage Reference and Linear Regulators • Operational Transconductance Amplifier • Analog Multipliers Edgar Sanchez-Sinencio, Texas A & M University ELEN 457 BRIEF OP AMP HISTORY - The Operational Amplifier (op amp) was invented in the 40’s. Bell Labs filed a patent in 1941 and many consider the first practical op amp to be the vacuum tube K2-W invented in 1952 by George Philbrick. - Texas Instruments invented the integrated circuit in 1958 which paved the way for Bob Widlar at Fairchild inventing the uA702 solid state monolithic op amp in 1963. - But it wasn’t until the uA741, released in 1968, that op amps became relatively inexpensive and started on the road to ubiquity. And they didn’t find their way into much consumer audio gear until the late 70’s and early 80’s http://nwavguy.blogspot.com/2011/08/op-amps-myths-facts.html Edgar Sanchez-Sinencio, Texas A & M University3 ELEN 457 WHERE DO YOU USE OP AMP? • Audio Amplifiers • Low Dropout Regulators • Active Filters • Medical Sensor Interfaces • Baseband Receivers • Analog to Digital Converters • Oscillators • Signal Generators • Hearing Aids Edgar Sanchez-Sinencio, Texas A & M University4 ELEN 457 • What is an amplifier? An amplifier is a device that increases its input by a certain quantity, passing through it, called gain. -

Power Converters: Definitions, Classification and Converter Topologies

Power converters: definitions, classification and converter topologies F. Bordry CERN, Geneva, Switzerland Abstract This paper introduces power conversion principles and defines the terminology. The concepts of sources and switches are defined and classified. From the basic laws of source interconnections, a generic method of power converter synthesis is presented. Some examples illustrate this systematic method. Finally, the notions of commutation cell and soft commutation are introduced and discussed. 1 Introduction The task of a power converter is to process and control the flow of electric energy by supplying voltages and currents in a form that is optimally suited for the user loads. Energy was initially converted in electromechanical converters (mostly rotating machines). Today, with the development and the mass production of power semiconductors, static power converters find applications in numerous domains and especially in particle accelerators. They are smaller and lighter and their static and dynamic performances are better. A static converter is a meshed network of electrical components that acts as a linking, adapting or transforming stage between two sources, generally between a generator and a load (Fig. 1). Fig. 1: Power converter definition An ideal static converter controls the flow of power between the two sources with 100% efficiency. Power converter design aims at improving the efficiency. But in a first approach and to define basic topologies, it is interesting to assume that no loss occurs in the converter process of a power converter. With this hypothesis, the basic elements are of two types: – non-linear elements, mainly electronic switches: semiconductors used in commutation mode [1]; – linear reactive elements: capacitors, inductances and mutual inductances or transformers.