Choice of Law for Void Contracts and Their Restitutionary Aftermath

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CIVIL ACTION FRANK FUMAI, : : Plaintiff, : : V. : : HARVEY LEVY, SUBURBAN : THERAPY, INC., and : SUBURBAN MEDICAL ASSOCIATES, : : Defendants

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF PENNSYLVANIA : CIVIL ACTION FRANK FUMAI, : : Plaintiff, : : v. : : HARVEY LEVY, SUBURBAN : THERAPY, INC., and : SUBURBAN MEDICAL ASSOCIATES, : : Defendants. : NO. 95-1674 M E M O R A N D U M Reed, J. January 16, 1998 The Court issues this memorandum in support of its Order dated January 9, 1998 (Document No. 42), in which the Court denied the motion of defendants Harvey Levy (“Levy”), Suburban Therapy, Inc. (“ST”), and Suburban Medical Associates (“SM”) (collectively “the defendants”) for partial reconsideration of the Order dated December 19, 1997 (Document No. 38) and granted in part the renewed motion of plaintiff Frank Fumai (“Fumai”) in limine to exclude all evidence and argument at trial that pertains or relates to the defendants’ claim or defense that Fumai breached a fiduciary duty owed to Allegheny United Hospitals (“Allegheny”) in connection with the sale of the assets of ST and SM to Allegheny (Document No. 37). I. BACKGROUND The following background facts are undisputed.1 On November 1, 1990, Fumai entered into an agreement with the defendants whereby Fumai would receive a commission from the sale of capital stock or assets of ST and SM if he procured a purchaser or introduced a party to the defendants who later introduced or procured a purchaser. Under the agreement, Fumai would receive 10% of the purchase price of ST and 5% of the purchase price of SM for such a sale. At the time of the contract between Fumai and the defendants, the main business of ST was the management of physician care services, including management of SM. -

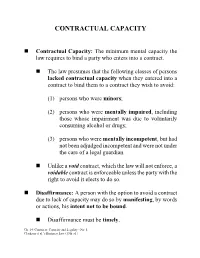

Contractual Capacity

CONTRACTUAL CAPACITY Contractual Capacity: The minimum mental capacity the law requires to bind a party who enters into a contract. The law presumes that the following classes of persons lacked contractual capacity when they entered into a contract to bind them to a contract they wish to avoid: (1) persons who were minors; (2) persons who were mentally impaired, including those whose impairment was due to voluntarily consuming alcohol or drugs; (3) persons who were mentally incompetent, but had not been adjudged incompetent and were not under the care of a legal guardian. Unlike a void contract, which the law will not enforce, a voidable contract is enforceable unless the party with the right to avoid it elects to do so. Disaffirmance: A person with the option to avoid a contract due to lack of capacity may do so by manifesting, by words or actions, his intent not to be bound. Disaffirmance must be timely. Ch. 14: Contracts: Capacity and Legality - No. 1 Clarkson et al.’s Business Law (13th ed.) MINORITY Subject to certain exceptions, an unmarried legal minor (in most states, someone less than 18 years old) may avoid a contract that would bind him if he were an adult. Contracts entered into by young children and contracts for something the law permits only for adults (e.g., a contract to purchase cigarettes or alcohol) are generally void, rather than voidable. Right to Disaffirm: Generally speaking, a minor may disaffirm a contract at any time during minority or for a reasonable time after he comes of age. When a minor disaffirms a contract, he can recover all property that he has transferred as consideration – even if it was subsequently transferred to a third party. -

Unit 6 – Contracts

Unit 6 – Contracts I. Definition A contract is a voluntary agreement between two or more parties that a court will enforce. The rights and obligations created by a contract apply only to the parties to the contract (i.e., those who agreed to them) and not to anyone else. II. Elements In order for a contract to be valid, certain elements must exist: (A) Competent parties. In order for a contract to be enforceable, the parties must have legal capacity. Even though most people can enter into binding agreements, there are some who must be protected from deception. The parties must be over the age of majority (18 under most state laws) and have sufficient mental capacity to understand the significance of the contract. Regarding the age requirement, if a minor enters a contract, that agreement can be voided by the minor but is binding on the other party, with some exceptions. (Contracts that a minor makes for necessaries such as food, clothing, shelter or transportation are generally enforceable.) This is called a voidable contract, which means that it will be valid (if all other elements are present) unless the minor wants to terminate it. The consequences of a minor avoiding a contract may be harsh to the other party. The minor need only return the subject matter of the contract to avoid the contract. if the subject matter of the contract is damaged the loss belongs to the nonavoiding party, not the minor. Regarding the mental capacity requirement, if the mental capacity of a party is so diminished that he cannot understand the nature and the consequences of the transaction, then that contract is also voidable (he can void it but the other party can not). -

Federalizing Contract Law

LCB_24_1_Article_5_Plass_Correction (Do Not Delete) 3/6/2020 10:06 AM FEDERALIZING CONTRACT LAW by Stephen A. Plass* Contract law is generally understood as state common law, supplemented by the Second Restatement of Contracts and Article 2 of the Uniform Commercial Code. It is regarded as an expression of personal liberty, anchored in the bar- gain and consideration model of the 19th century or classical period. However, for some time now, non-bargained or adhesion contracts have been the norm, and increasingly, the adjudication of legal rights and contractual remedies is controlled by privately determined arbitration rules. The widespread adoption of arbitral adjudication by businesses has been enthusiastically endorsed by the Supreme Court as consonant with the Federal Arbitration Act (“FAA”). How- ever, Court precedents have concluded that only bilateral or individualized arbitration promotes the goals of the FAA, while class arbitration is destruc- tive. Businesses and the Court have theorized that bilateral arbitration is an efficient process that reduces the transaction costs of all parties thereby permit- ting firms to reduce prices, create jobs, and innovate or improve products. But empirical research tells a different story. This Article discusses the constitu- tional contours of crafting common law for the FAA and its impact on state and federal laws. It shows that federal common law rules crafted for the FAA can operate to deny consumers and workers the neoclassical contractual guar- antee of a minimum adequate remedy and rob the federal and state govern- ments of billions of dollars in tax revenue. From FAA precedents the Article distills new rules of contract formation, interpretation, and enforcement and shows how these new rules undermine neoclassical limits on private control of legal remedies. -

Relative Consent and Contract Law

18 NEV. L.J. 165, KIM - FINAL 12/15/17 12:41 PM RELATIVE CONSENT AND CONTRACT LAW Nancy S. Kim* What does it mean to consent? Consent is an essential component of contracts, yet its part in contract law is obscure. Despite its importance, there is no independ- ent doctrine of consent; rather, it plays a key, but ill-defined role in assessing doc- trines such as assent or duress. This Article addresses this significant omission in contract law by disassembling the meaning of contractual consent into three con- ditions: an intentional act or manifestation of consent, voluntariness and knowledge. This Article argues that consent can only be understood relative to these three conditions. Accordingly, consent is not merely a conclusion but a pro- cess and a dynamic that depends upon a variety of factors, including the relative blameworthiness of the parties, their relationship, third party effects and societal impact. This Article, through an examination of classic and modern cases, demon- strates how the concept of relative consent provides a coherent framework for un- derstanding contract law. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................... 166 I. CONSENT CONSTRUCTION AND CONSENT DESTRCUTION .......... 169 A. Consent Construction .......................................................... 170 1. Intentional Manifestation of Consent ........................... 171 2. The Knowledge Condition ............................................ 172 3. Voluntariness ............................................................... -

Lesson 9: Contract Law

Real Estate Principles of Georgia Lesson 9: Contract Law 1 of 72 201 Introduction Contract: An agreement between two or more persons to do, or not do, certain things. 202 © Copyright, 2006, Rockwell Publishing, Inc. Legal Classification of Contracts Every contract is: y express or implied y unilateral or bilateral y executory or executed 202 © Copyright, 2006, Rockwell Publishing, Inc. 1 Legal Classification of Contracts Express vs. implied Express contract: One that is put into words, whether oral or written. Implied contract: One not expressed in words, but implied by the parties’ actions. Most contracts are express, not implied. 202 © Copyright, 2006, Rockwell Publishing, Inc. Legal Classification of Contracts Unilateral vs. bilateral Unilateral contract: Only one party promises to do something and is legally obligated to perform as promised. Bilateral contract: Both parties promise to do something and are legally obligated to perform as promised. Most contracts are bilateral. 202 © Copyright, 2006, Rockwell Publishing, Inc. Legal Classification of Contracts Executory vs. executed Executory: Contract is in the process of being performed. Executed: Contract has been fully performed; both parties have fulfilled their promises. 203 © Copyright, 2006, Rockwell Publishing, Inc. 2 Summary Legal Classification of Contracts Contract Express or implied Unilateral or bilateral Executory or executed © Copyright, 2006, Rockwell Publishing, Inc. Elements of a Valid Contract Valid contract: A legally binding contract (will be enforced by court if one party fails to comply). Valid contract must have: y parties with legal capacity y mutual consent y lawful objective y consideration 203 © Copyright, 2006, Rockwell Publishing, Inc. Elements of a Valid Contract Contractual capacity Contract is not legally binding unless all parties have legal capacity to enter into it. -

Contracts Professor Keith A

Contracts Professor Keith A. Rowley William S. Boyd School of Law University of Nevada Las Vegas Spring 2009 Formation Defenses I. “Void” vs. “Voidable” Contracts A. “Void” Contract: A contract that is unenforceable as a matter of law (e.g., a contract for child prostitution). B. “Voidable” Contract: An otherwise enforceable contract that a party may avoid, as a matter of fact, based on one of the following defenses. ♦ A party’s acts or statements after her right to avoidance arises (e.g., ratification or reaffirmance) may cut off her ability to avoid a contract. II. Lack of Capacity A. Contractual Capacity: The minimum legal capacity required to bind a party to a contract he, she, or it allegedly made. ♦ Because incapacity may be transient, the key is whether the party has or lacks capacity when the contract forms. B. Minority: Unmarried minors may enter into any contract an adult can, provided that the contract is not illegal for a minor (e.g., an agreement to buy cigarettes). 1. Voidability: Unlike those entered into by adults, contracts entered into by minors are generally voidable. ♦ Most states recognize an age before which a contract with a minor is void. 2. Disaffirmance: In order for a minor to avoid or set aside a contract, she need only manifest her intention not to be bound by it. a. The minor may manifest her intent to avoid by words or actions. b. Generally speaking, a minor may disaffirm a contract at any time before and for a reasonable time after the minor comes of age. -

Unconscionability As a Sword: the Case for an Affirmative Cause of Action

Unconscionability as a Sword: The Case for an Affirmative Cause of Action Brady Williams* Consumers are drowning in a sea of one-sided fine print. To combat contractual overreach, consumers need an arsenal of effective remedies. To that end, the doctrine of unconscionability provides a crucial defense against the inequities of rigid contract enforcement. However, the prevailing view that unconscionability operates merely as a “shield” and not a “sword” leaves countless victims of oppressive contracts unable to assert the doctrine as an affirmative claim. This crippling interpretation betrays unconscionability’s equitable roots and absolves merchants who have already obtained their ill-gotten gains. But this need not be so. Using California consumer credit law as a backdrop, this Note argues that the doctrine of unconscionability must be recrafted into an offensive sword that provides affirmative relief to victims of unconscionable contracts. While some consumers may already assert unconscionability under California’s Consumers Legal Remedies Act, courts have narrowly construed the Act to exempt many forms of consumer credit. As a result, thousands of debtors have remained powerless to challenge their credit terms as unconscionable unless first sued by a creditor. However, this Note explains how a recent landmark ruling by the California Supreme Court has confirmed a novel legal theory that broadly empowers consumers—including debtors—to assert unconscionability under the State’s Unfair Competition Law. Finally, this Note argues that unconscionability’s historical roots in courts of equity—as well as its treatment by the DOI: https://doi.org/10.15779/Z382B8VC3W Copyright © 2019 California Law Review, Inc. California Law Review, Inc. -

Understanding the Nature of Void and Voidable Contracts Jesse A

Campbell Law Review Volume 33 Article 6 Issue 1 Fall 2010 January 2010 Beyond a Definition: Understanding the Nature of Void and Voidable Contracts Jesse A. Schaefer Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.campbell.edu/clr Part of the Contracts Commons Recommended Citation Jesse A. Schaefer, Beyond a Definition: Understanding the Nature of Void and Voidable Contracts, 33 Campbell L. Rev. 193 (2010). This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Repository @ Campbell University School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Campbell Law Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Repository @ Campbell University School of Law. Schaefer: Beyond a Definition: Understanding the Nature of Void and Voidabl Beyond a Definition: Understanding the Nature of Void and Voidable Contracts* INTRODUCTION Contract law has a problem.' With predictable recurrence, court opinions, statutes, scholarly literature, and contract draftsmen use the words "void," "voidable," and "unenforceable" - as well as dozens of other terms of the same ilk - to describe flawed contracts. Yet the meaning of these declarations is persistently and maddeningly slippery. In the rare case where the precise meanings of these words are pressed into service in the courtroom, litigants are often surprised to find the court announce that a transaction formerly (and unequivocally) declared to be void is, in fact, merely voidable or unenforceable.2 The scope of the problem is as widespread as it is trifled; though the distinction between void and voidable is sometimes the most important issue in contract disputes, very little serious, scholarly attention has been paid to the nature of the distinction. -

Misrepresentation: the Restatement’S Second Mistake

HOFFER.DOCX (DO NOT DELETE) 1/31/2014 2:04 PM MISREPRESENTATION: THE RESTATEMENT’S SECOND MISTAKE Stephanie R. Hoffer* The contract defenses of mistake and misrepresentation can be used to unravel deals as big as a corporate merger and as small as the sale of a used car. These two defenses, while conceptually distinct in theory, contain a significant amount of overlap in practice, causing courts to conflate the two legal standards. A misrepresentation of one party, when believed, results in a mistaken belief of the other, and both defenses address fundamental flaws in bargaining that throw the contracting parties’ consent into question. The coextensiveness of the defenses suggests that, absent an overriding normative justification, the legal test and remedy should be the same for each. Such a norma- tive justification exists only in the case of fraudulent misrepresentation which, unlike mistake or nonfraudulent misrepresentation, involves the intentional infliction of a dignitary harm. In such cases, punish- ment and deterrence are appropriate normative goals but neither are addressed by currently prevailing common law. Providing a single test for cases of misrepresentation and mistake with recourse to puni- tive damages in cases of fraud would harmonize the defenses with their normative underpinnings and eliminate inefficient redundancies in the common law. TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................. 117 II. MISTAKE ........................................................................................... -

Quantum Meruit Recovery on Unenforceable Contracts Cyrus D

Marquette Law Review Volume 11 Article 6 Issue 4 June 1927 Quantum Meruit Recovery on Unenforceable Contracts Cyrus D. Schabaz Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/mulr Part of the Law Commons Repository Citation Cyrus D. Schabaz, Quantum Meruit Recovery on Unenforceable Contracts, 11 Marq. L. Rev. 235 (1927). Available at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/mulr/vol11/iss4/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Marquette Law Review by an authorized administrator of Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. QUANTUM MERUIT RECOVERY ON UNENFORCEABLE CONTRACTS CYRUS D. SCHABAZ T HIS article is to deal with the unenforceable contracts, not those unenforceable because of moral turpitude or immorality, but those contracts malum prohibitum through some statute or settled public pol- icy. The scope of this article will show what contracts are unenforce- able, how recovery can be maintained nevertheless, and what is neces- sary to show the implied contract, together with a recommendation as to how the doctrine of quantum reruit should be extended. The article will be divided into three parts: Contracts void under the statute of frauds, personal service contracts, and Sunday contracts, to be treated in the order mentioned. At the outset the statutes under consideration should be set forth. The section relating to real estate is 240.06. Conveyance of land, etc., to be in writing. No estate or interest in lInds,- other than leases for a term not exceeding one year, nor any trust or power over or concerning lands in any manner relating thereto shall be created, granted, assigned, surrendered or declared unless by act or operation of law or by deed or conveyance in writing subscribed by the party creating, granting, assigning, surrendering or declaring the same or by his lawful agent thereto authorized in writing. -

Restitution Under the Statute of Frauds: What Constitutes a Legal Benefit

Indiana Law Journal Volume 26 Issue 1 Article 1 Fall 1950 Restitution Under the Statute of Frauds: What Constitutes A Legal Benefit Lindsey R. Jeanblanc Washington University Follow this and additional works at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Jeanblanc, Lindsey R. (1950) "Restitution Under the Statute of Frauds: What Constitutes A Legal Benefit," Indiana Law Journal: Vol. 26 : Iss. 1 , Article 1. Available at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj/vol26/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Indiana Law Journal by an authorized editor of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INDIANA LAW JOURNAL Volume 26 FALL 1950 Number I RESTITUTION UNDER THE STATUTE OF FRAUDS: WHAT CONSTITUTES A LEGAL BENEFIT* LINDSEY R. JEANBLANCt I. PERFORMANCE OF ORAL AGREEMENT AS LEGAL BENEFIT 1. INTRODUCTION Although the original English Statute of Frauds" was enacted over two hundred seventy years ago, its provisions, with minor variations, have been adopted in virtually all of the states and territories of the United States.2 The amount of litigation concerning the Statute of Frauds continues to be tremendous.' This study of restitution under the Statute4 involves an exami- nation of the effect of the Statute of Frauds upon oral agreements which fail to comply with its requirements; but we are not concerned with the problem of determining what contracts must meet the requirements of the Statute to be enforceable,5 or what constitutes a satisfaction of its provisions., * This article is one of a series submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of the Science of Law, in the Faculty of Law, Columbia University.