MISTAKE and FRUSTRATION

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Dispute 30:2 Contract Formation

CHAPTER 30 CONTRACTS Introductory Note A. CONTRACT FORMATION 30:1 Contract Formation ― In Dispute 30:2 Contract Formation ― Need Not Be in Writing 30:3 Contract Formation ― Offer 30:4 Contract Formation ― Revocation of Offer 30:5 Contract Formation ― Counteroffer 30:6 Contract Formation ― Acceptance 30:7 Contract Formation ― Consideration 30:8 Contract Formation ― Modification 30:9 Contract Formation ― Third-Party Beneficiary B. CONTRACT PERFORMANCE 30:10 Contract Performance — Breach of Contract — Elements of Liability 30:11 Contract Performance — Breach of Contract Defined 30:12 Contract Performance — Substantial Performance 30:13 Contract Performance — Anticipatory Breach 30:14 Contract Performance — Time of Performance 30:15 Contract Performance — Conditions Precedent 30:16 Contract Performance — Implied Duty of Good Faith and Fair Dealing — Non-Insurance Contract 30:17 Contract Performance — Assignment C. DEFENSES Introductory Note 30:18 Defense — Fraud in the Inducement 30:19 Defense — Undue Influence 30:20 Defense — Duress 30:21 Defense — Minority 30:22 Defense — Mental Incapacity 30:23 Defense — Impossibility of Performance 30:24 Defense — Inducing a Breach by Words or Conduct 30:25 Defense — Waiver 30:26 Defense — Statute of Limitations 30:27 Defense — Cancellation by Agreement 30:28 Defense — Accord and Satisfaction (Later Contract) 30:29 Defense — Novation D. CONTRACT INTERPRETATION Introductory Note 30:30 Contract Interpretation — Disputed Term 30:31 Contract Interpretation — Parties’ Intent 30:32 Contract Interpretation — -

DDS WIRELESS INTERNATIONAL, INC. V. NUTMEG LEASING, INC. (AC 34278) Robinson, Bear and Peters, Js

****************************************************** The ``officially released'' date that appears near the beginning of each opinion is the date the opinion will be published in the Connecticut Law Journal or the date it was released as a slip opinion. The operative date for the beginning of all time periods for filing postopinion motions and petitions for certification is the ``officially released'' date appearing in the opinion. In no event will any such motions be accepted before the ``officially released'' date. All opinions are subject to modification and technical correction prior to official publication in the Connecti- cut Reports and Connecticut Appellate Reports. In the event of discrepancies between the electronic version of an opinion and the print version appearing in the Connecticut Law Journal and subsequently in the Con- necticut Reports or Connecticut Appellate Reports, the latest print version is to be considered authoritative. The syllabus and procedural history accompanying the opinion as it appears on the Commission on Official Legal Publications Electronic Bulletin Board Service and in the Connecticut Law Journal and bound volumes of official reports are copyrighted by the Secretary of the State, State of Connecticut, and may not be repro- duced and distributed without the express written per- mission of the Commission on Official Legal Publications, Judicial Branch, State of Connecticut. ****************************************************** DDS WIRELESS INTERNATIONAL, INC. v. NUTMEG LEASING, INC. (AC 34278) Robinson, Bear and Peters, Js. Argued March 21Ðofficially released September 10, 2013 (Appeal from Superior Court, judicial district of Ansonia-Milford, Hon. John W. Moran, judge trial referee.) Linda L. Morkan, with whom, on the brief, was Christopher J. -

The Civilian Impact of Drone Strikes

THE CIVILIAN IMPACT OF DRONES: UNEXAMINED COSTS, UNANSWERED QUESTIONS Acknowledgements This report is the product of a collaboration between the Human Rights Clinic at Columbia Law School and the Center for Civilians in Conflict. At the Columbia Human Rights Clinic, research and authorship includes: Naureen Shah, Acting Director of the Human Rights Clinic and Associate Director of the Counterterrorism and Human Rights Project, Human Rights Institute at Columbia Law School, Rashmi Chopra, J.D. ‘13, Janine Morna, J.D. ‘12, Chantal Grut, L.L.M. ‘12, Emily Howie, L.L.M. ‘12, Daniel Mule, J.D. ‘13, Zoe Hutchinson, L.L.M. ‘12, Max Abbott, J.D. ‘12. Sarah Holewinski, Executive Director of Center for Civilians in Conflict, led staff from the Center in conceptualization of the report, and additional research and writing, including with Golzar Kheiltash, Erin Osterhaus and Lara Berlin. The report was designed by Marla Keenan of Center for Civilians in Conflict. Liz Lucas of Center for Civilians in Conflict led media outreach with Greta Moseson, pro- gram coordinator at the Human Rights Institute at Columbia Law School. The Columbia Human Rights Clinic and the Columbia Human Rights Institute are grateful to the Open Society Foundations and Bullitt Foundation for their financial support of the Institute’s Counterterrorism and Human Rights Project, and to Columbia Law School for its ongoing support. Copyright © 2012 Center for Civilians in Conflict (formerly CIVIC) and Human Rights Clinic at Columbia Law School All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America. Copies of this report are available for download at: www.civiliansinconflict.org Cover: Shakeel Khan lost his home and members of his family to a drone missile in 2010. -

THE DOCTRINE of CARLISLE and CUMBERLAND BANKING CO. V

661 THE DOCTRINE OF CARLISLE AND CUMBERLAND BANKING CO. v. BRAGG.* The facts of this well known case. are that Bragg was induced by the fraud of Rigg to, sign a guarantee of the latter's debts upon;. the representation that it was an insurance paper. On an occasion when Rigg and the defendant had been drinking together, Rigg produced a paper purporting to relate to insurance, and asked Bragg to sign it, explaining that a similar paper which Bragg had signed on a previous day had become wet and blurred by the rain. The defendant signed without reading it. In an action brought by the Bank an the guarantee,-Bragg pleaded non est factum. The jury found that the defendant did not know that the document was a guarantee, and that he was negligent in signing. The Court of Appeal held that, in contemplation of law, Bragg had never signed the instrument, and that his negligence did not estop him from setting up the plea of anon est factum. Before this decision there was a strong current of long recognized authority for the proposition that a person who negligently executes an instrument is estopped as against third parties who acquired rights under it.' Thoroughgood's Case is the first decision.. Lord Coke held that if a deed be explained in wards other than the truth it shall not bind the unlettered layman who is deceived.3 Skinner reports a case where the court commented on a defendant's liability under a carelessly signed lease; "being able to read it was his own folly, otherwise if he had been unlettered."3a Sheppard declares that if a party who can read seals a deed without reading it, or if illiterate or blind, without requiring it to be read over to him, then although the deed be contrary to his mind, it is good and unavoid- able.4 Thus, in the absence of negligence the illiteracy of the person *This article was submitted in the competition for the Carswell Essay Prize in Dalhousie Law School and was given first place by the Faculty. -

Entrapment, Shocked Consciences, and the Staged Arrest Bennett L

University of Minnesota Law School Scholarship Repository Minnesota Law Review 1982 Entrapment, Shocked Consciences, and the Staged Arrest Bennett L. Gershman Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/mlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Gershman, Bennett L., "Entrapment, Shocked Consciences, and the Staged Arrest" (1982). Minnesota Law Review. 890. https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/mlr/890 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Minnesota Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Minnesota Law Review collection by an authorized administrator of the Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Entrapment, Shocked Consciences, and the Staged Arrest Bennett L. Gershman* I. INTRODUCTION On November 1, 1973, in the Criminal Court of the City of New York, Kings County, Stephen Vitale was arraigned on a charge of armed robbery. According to the complaining wit- ness, Morton Hirsch, Vitale placed a pistol against Hirsch's head, threatened him, and robbed him of over $8,000. The sup- porting affidavit of Police Officer Brian Cosgrove stated that as Vitale was fleeing from the robbery scene, Cosgove arrested him and seized a pistol from him.' On the surface, this proceeding appeared no different from thousands of similar proceedings taking place daily in criminal courts throughout the country. In fact, Vitale, Hirsch, and Cos- grove were undercover agents; New York's Special Anti-Cor- ruption Prosecutor had authorized their activities 2 as part of a program to detect corruption in the criminal justice system. 3 False court documents, false statements made to judges, and * Associate Professor of Law, Pace University School of Law. -

CIVIL ACTION FRANK FUMAI, : : Plaintiff, : : V. : : HARVEY LEVY, SUBURBAN : THERAPY, INC., and : SUBURBAN MEDICAL ASSOCIATES, : : Defendants

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF PENNSYLVANIA : CIVIL ACTION FRANK FUMAI, : : Plaintiff, : : v. : : HARVEY LEVY, SUBURBAN : THERAPY, INC., and : SUBURBAN MEDICAL ASSOCIATES, : : Defendants. : NO. 95-1674 M E M O R A N D U M Reed, J. January 16, 1998 The Court issues this memorandum in support of its Order dated January 9, 1998 (Document No. 42), in which the Court denied the motion of defendants Harvey Levy (“Levy”), Suburban Therapy, Inc. (“ST”), and Suburban Medical Associates (“SM”) (collectively “the defendants”) for partial reconsideration of the Order dated December 19, 1997 (Document No. 38) and granted in part the renewed motion of plaintiff Frank Fumai (“Fumai”) in limine to exclude all evidence and argument at trial that pertains or relates to the defendants’ claim or defense that Fumai breached a fiduciary duty owed to Allegheny United Hospitals (“Allegheny”) in connection with the sale of the assets of ST and SM to Allegheny (Document No. 37). I. BACKGROUND The following background facts are undisputed.1 On November 1, 1990, Fumai entered into an agreement with the defendants whereby Fumai would receive a commission from the sale of capital stock or assets of ST and SM if he procured a purchaser or introduced a party to the defendants who later introduced or procured a purchaser. Under the agreement, Fumai would receive 10% of the purchase price of ST and 5% of the purchase price of SM for such a sale. At the time of the contract between Fumai and the defendants, the main business of ST was the management of physician care services, including management of SM. -

Indemnity: "Pass-Through" Provisions

Indemnity: "Pass-Through" Provisions January 2005 by: James Donohue, Esq. and Edward M. Koch, Esq. Overlooking the subtle nuances of indemnity provisions in a proposed contract is a common—and often costly—mistake. Parties eager to win a bid often look past contract language which can require them to pay not only for their own mistakes, but for those of another party, too. (For more background on indemnity, see, “Who Pays For Your Mistakes”, Executive Newsletter, Fall 2004, located in the Publications Section of www.whiteandwilliams.com). For matters being decided under Pennsylvania law, a recent Supreme Court decision illuminates a previously dim region of the indemnity landscape. In Bernotas v. Super Fresh Food Markets, Inc., the Court substantially abrogates the use of so-called “pass-through,” “conduit,” or “flow-through” indemnification provisions that are common in construction subcontracts. Under the Supreme Court’s decision, “passthrough” indemnification provisions will only be valid if the indemnification obligation is stated in clear and unequivocal terms. Form book or cut-and-paste boilerplate won’t do. INDEMNIFICATION, GENERALLY Indemnification refers to one party’s obligation to pay for the liability of another for certain specified events. The source of this obligation can be either through the common law or, as addressed by the Supreme Court in Bernotas, through contract. Historically, Pennsylvania courts have closely scrutinized contractual indemnification provisions. For example, one could seek indemnity from another for one’s own negligence, but general indemnity language was insufficient to affect this end. Instead, a clear and unequivocal statement of indemnification for one’s own negligence had to be clearly spelled-out in the contract provision in order for it to be effective under Pennsylvania law. -

Boston University Law Review

Boston University Law Review VOLUME XXI APRIL, 1941 NUMBER 2 STATE INDEMNITY FOR ERRORS OF CRIMINAL JUSTICE EDWIN BORCIIARD*BORCHARD* All too frequently the public is shocked by the news that Federal or State authorities have convicted and imprisoned a person subse-subse quently proved to have been innocent of any crime. These acciacci- dents in the administration of the criminal law happen either through an unfortunate concurrence of circumstances or perjured testimony or are the result of mistaken identity, the conviction having been obob- tained by zealous prosecuting attorneys on circumstantial evidence. In an earnest effort to compensate in some measure the victims of these miscarriages of justice, Congress in May 1938 enacted a law "to grant relief to persons erroneously convicted in courts of the United States." Under this law, any person who can prove that he was wrongwrong- fully convicted and sentenced for a crime against the United States may bring suit in the Court of Claims against the Federal Government for damages of not more than $5,000. The Federal act of May 24, 1938, limits the right of recovery to innocent persons who have been both convicted and served all or a part of their sentence. The innocence must be proved either by appeal or new trial or rehearing in which innocence is established, or by a pardon on the ground of innocence. ItIt must also appear that the en~oneouslyerroneously convicted person either committed none of the acts with which he was charged or that those acts constituted no crime against the United States or against any State or Territory. -

Force Majeure and Common Law Defenses | a National Survey | Shook, Hardy & Bacon

2020 — Force Majeure SHOOK SHB.COM and Common Law Defenses A National Survey APRIL 2020 — Force Majeure and Common Law Defenses A National Survey Contractual force majeure provisions allocate risk of nonperformance due to events beyond the parties’ control. The occurrence of a force majeure event is akin to an affirmative defense to one’s obligations. This survey identifies issues to consider in light of controlling state law. Then we summarize the relevant law of the 50 states and the District of Columbia. 2020 — Shook Force Majeure Amy Cho Thomas J. Partner Dammrich, II 312.704.7744 Partner Task Force [email protected] 312.704.7721 [email protected] Bill Martucci Lynn Murray Dave Schoenfeld Tom Sullivan Norma Bennett Partner Partner Partner Partner Of Counsel 202.639.5640 312.704.7766 312.704.7723 215.575.3130 713.546.5649 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] SHOOK SHB.COM Melissa Sonali Jeanne Janchar Kali Backer Erin Bolden Nott Davis Gunawardhana Of Counsel Associate Associate Of Counsel Of Counsel 816.559.2170 303.285.5303 312.704.7716 617.531.1673 202.639.5643 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] John Constance Bria Davis Erika Dirk Emily Pedersen Lischen Reeves Associate Associate Associate Associate Associate 816.559.2017 816.559.0397 312.704.7768 816.559.2662 816.559.2056 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Katelyn Romeo Jon Studer Ever Tápia Matt Williams Associate Associate Vergara Associate 215.575.3114 312.704.7736 Associate 415.544.1932 [email protected] [email protected] 816.559.2946 [email protected] [email protected] ATLANTA | BOSTON | CHICAGO | DENVER | HOUSTON | KANSAS CITY | LONDON | LOS ANGELES MIAMI | ORANGE COUNTY | PHILADELPHIA | SAN FRANCISCO | SEATTLE | TAMPA | WASHINGTON, D.C. -

A New Look at Contract Mistake Doctrine and Personal Injury Releases

19 NEV. L.J. 535, GIESEL 4/25/2019 8:36 PM A NEW LOOK AT CONTRACT MISTAKE DOCTRINE AND PERSONAL INJURY RELEASES Grace M. Giesel* “[C]ourts cannot make for the parties better agreements than they themselves have been satisfied to make.”1 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................... 536 I. THE SETTING: THE TYPICAL CASE ..................................................... 542 II. CONTRACT DOCTRINE APPLIES .......................................................... 544 III. CONTRACT MISTAKE DOCTRINE ......................................................... 545 IV. TRADITIONAL APPLICATION OF CONTRACT DOCTRINE TO THE TYPICAL PERSONAL INJURY RELEASE SITUATION.............................. 547 A. A Shared Mistake of Fact and Not a Speculation or Prediction . 547 B. The Injured Party Has the Risk of Mistake by Conscious Ignorance .................................................................................... 548 C. The Release Places the Risk of Mistake on the Injured Party ..... 549 D. Traditional Application of the Unilateral Mistake Doctrine to the Typical Personal Injury Release Situation ............................ 554 E. Conclusions about Traditional Application of the Mistake Doctrine ...................................................................................... 555 V. COURTS’ TREATMENT OF PERSONAL INJURY RELEASES .................... 555 A. Mistake Doctrine Applies with an Unknown Injury But Not with an Unknown Consequence of a Known Injury ................... -

Contractual Capacity

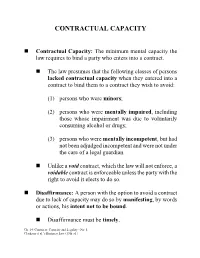

CONTRACTUAL CAPACITY Contractual Capacity: The minimum mental capacity the law requires to bind a party who enters into a contract. The law presumes that the following classes of persons lacked contractual capacity when they entered into a contract to bind them to a contract they wish to avoid: (1) persons who were minors; (2) persons who were mentally impaired, including those whose impairment was due to voluntarily consuming alcohol or drugs; (3) persons who were mentally incompetent, but had not been adjudged incompetent and were not under the care of a legal guardian. Unlike a void contract, which the law will not enforce, a voidable contract is enforceable unless the party with the right to avoid it elects to do so. Disaffirmance: A person with the option to avoid a contract due to lack of capacity may do so by manifesting, by words or actions, his intent not to be bound. Disaffirmance must be timely. Ch. 14: Contracts: Capacity and Legality - No. 1 Clarkson et al.’s Business Law (13th ed.) MINORITY Subject to certain exceptions, an unmarried legal minor (in most states, someone less than 18 years old) may avoid a contract that would bind him if he were an adult. Contracts entered into by young children and contracts for something the law permits only for adults (e.g., a contract to purchase cigarettes or alcohol) are generally void, rather than voidable. Right to Disaffirm: Generally speaking, a minor may disaffirm a contract at any time during minority or for a reasonable time after he comes of age. When a minor disaffirms a contract, he can recover all property that he has transferred as consideration – even if it was subsequently transferred to a third party. -

Unit 6 – Contracts

Unit 6 – Contracts I. Definition A contract is a voluntary agreement between two or more parties that a court will enforce. The rights and obligations created by a contract apply only to the parties to the contract (i.e., those who agreed to them) and not to anyone else. II. Elements In order for a contract to be valid, certain elements must exist: (A) Competent parties. In order for a contract to be enforceable, the parties must have legal capacity. Even though most people can enter into binding agreements, there are some who must be protected from deception. The parties must be over the age of majority (18 under most state laws) and have sufficient mental capacity to understand the significance of the contract. Regarding the age requirement, if a minor enters a contract, that agreement can be voided by the minor but is binding on the other party, with some exceptions. (Contracts that a minor makes for necessaries such as food, clothing, shelter or transportation are generally enforceable.) This is called a voidable contract, which means that it will be valid (if all other elements are present) unless the minor wants to terminate it. The consequences of a minor avoiding a contract may be harsh to the other party. The minor need only return the subject matter of the contract to avoid the contract. if the subject matter of the contract is damaged the loss belongs to the nonavoiding party, not the minor. Regarding the mental capacity requirement, if the mental capacity of a party is so diminished that he cannot understand the nature and the consequences of the transaction, then that contract is also voidable (he can void it but the other party can not).