Relative Consent and Contract Law

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contracts Course

Contracts A Contract A contract is a legally enforceable agreement between two or more parties with mutual obligations. The remedy at law for breach of contract is "damages" or monetary compensation. In equity, the remedy can be specific performance of the contract or an injunction. Both remedies award the damaged party the "benefit of the bargain" or expectation damages, which are greater than mere reliance damages, as in promissory estoppels. Origin and Scope Contract law is based on the principle expressed in the Latin phrase pacta sunt servanda, which is usually translated "agreements to be kept" but more literally means, "pacts must be kept". Contract law can be classified, as is habitual in civil law systems, as part of a general law of obligations, along with tort, unjust enrichment, and restitution. As a means of economic ordering, contract relies on the notion of consensual exchange and has been extensively discussed in broader economic, sociological, and anthropological terms. In American English, the term extends beyond the legal meaning to encompass a broader category of agreements. Such jurisdictions usually retain a high degree of freedom of contract, with parties largely at liberty to set their own terms. This is in contrast to the civil law, which typically applies certain overarching principles to disputes arising out of contract, as in the French Civil Code. However, contract is a form of economic ordering common throughout the world, and different rules apply in jurisdictions applying civil law (derived from Roman law principles), Islamic law, socialist legal systems, and customary or local law. 2014 All Star Training, Inc. -

In Dispute 30:2 Contract Formation

CHAPTER 30 CONTRACTS Introductory Note A. CONTRACT FORMATION 30:1 Contract Formation ― In Dispute 30:2 Contract Formation ― Need Not Be in Writing 30:3 Contract Formation ― Offer 30:4 Contract Formation ― Revocation of Offer 30:5 Contract Formation ― Counteroffer 30:6 Contract Formation ― Acceptance 30:7 Contract Formation ― Consideration 30:8 Contract Formation ― Modification 30:9 Contract Formation ― Third-Party Beneficiary B. CONTRACT PERFORMANCE 30:10 Contract Performance — Breach of Contract — Elements of Liability 30:11 Contract Performance — Breach of Contract Defined 30:12 Contract Performance — Substantial Performance 30:13 Contract Performance — Anticipatory Breach 30:14 Contract Performance — Time of Performance 30:15 Contract Performance — Conditions Precedent 30:16 Contract Performance — Implied Duty of Good Faith and Fair Dealing — Non-Insurance Contract 30:17 Contract Performance — Assignment C. DEFENSES Introductory Note 30:18 Defense — Fraud in the Inducement 30:19 Defense — Undue Influence 30:20 Defense — Duress 30:21 Defense — Minority 30:22 Defense — Mental Incapacity 30:23 Defense — Impossibility of Performance 30:24 Defense — Inducing a Breach by Words or Conduct 30:25 Defense — Waiver 30:26 Defense — Statute of Limitations 30:27 Defense — Cancellation by Agreement 30:28 Defense — Accord and Satisfaction (Later Contract) 30:29 Defense — Novation D. CONTRACT INTERPRETATION Introductory Note 30:30 Contract Interpretation — Disputed Term 30:31 Contract Interpretation — Parties’ Intent 30:32 Contract Interpretation — -

HORIZON VENTURES of WEST VIRGINIA, INC., a WEST VIRGINIA CORPORATION, Plaintiff Below, Petitioner

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF APPEALS OF WEST VIRGINIA January 2021 Term FILED _____________ April 1, 2021 released at 3:00 p.m. No. 19-0171 EDYTHE NASH GAISER, CLERK SUPREME COURT OF APPEALS _____________ OF WEST VIRGINIA HORIZON VENTURES OF WEST VIRGINIA, INC., A WEST VIRGINIA CORPORATION, Plaintiff Below, Petitioner V. AMERICAN BITUMINOUS POWER PARTNERS, L.P., Defendant Below, Respondent ________________________________________________ Appeal from the Circuit Court of Marion County The Honorable Patrick N. Wilson, Judge Civil Action No. 18-C-76 REVERSED AND REMANDED ________________________________________________ Submitted: February 9, 2021 Filed: April 1, 2021 Mark A. Kepple John F. McCuskey Bailey & Wyant, PLLC Roberta F. Green Wheeling, West Virginia Shuman, McCuskey, & Slicer PLLC Attorney for the Petitioner Charleston, West Virginia Attorneys for the Respondent CHIEF JUSTICE JENKINS delivered the Opinion of the Court. JUSTICES HUTCHISON and WOOTON concur and reserve the right to file concurring opinions. SYLLABUS BY THE COURT 1. “A circuit court’s entry of summary judgment is reviewed de novo.” Syllabus point 1, Painter v. Peavy, 192 W. Va. 189, 451 S.E.2d 755 (1994). 2. “‘A motion for summary judgment should be granted only when it is clear that there is no genuine issue of fact to be tried and inquiry concerning the facts is not desirable to clarify the application of the law.’ Syllabus Point 3, Aetna Casualty & Surety Co. v. Federal Insurance Co. of New York, 148 W. Va. 160, 133 S.E.2d 770 (1963).” Syllabus point 1, Andrick v. Town of Buckhannon, 187 W. Va. 706, 421 S.E.2d 247 (1992). -

Chapter 4 the Economics of Contract Law I: the Elements of a Valid

Chapter 4 The Economics of Contract Law I: The Elements of a Valid Contract This chapter begins the analysis of contract law by describing the elements that constitute a valid contract. Specifically, it asks what must be true of a promise for it to be legally enforceable. Key Points Contract law provides the legal background for economic exchange by enforcing voluntary agreements. Contracts cannot always provide for contingencies that might arise between the formation of the contract and the performance date. The economic theory of contract law says that courts should supply the missing terms in these incomplete contracts so as to maximize the gains from trade. From a legal perspective, a valid contract includes three elements: offer, acceptance, and consideration. When offer and acceptance are present, the parties are said to have achieved a “meeting of the minds.” Consideration is the return promise that makes a contract mutual. Consideration need not be a monetary payment. It can also be a voluntary surrender of a legal right. Under traditional contract law, courts only inquire into the presence of consideration, not its form or adequacy. A contract is invalid if one or both of the parties is mentally incompetent; if one of the parties entered the contract under coercion or duress; if the contract involves a mutual mistake; or if the terms of the contract are unconscionable. These excuses are referred to as formation defenses. The proper economic interpretation of coercion or duress is that it concerns prevention of monopoly. The doctrine of mistake concerns the rules for disclosure of private information prior to contracting. -

CIVIL ACTION FRANK FUMAI, : : Plaintiff, : : V. : : HARVEY LEVY, SUBURBAN : THERAPY, INC., and : SUBURBAN MEDICAL ASSOCIATES, : : Defendants

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF PENNSYLVANIA : CIVIL ACTION FRANK FUMAI, : : Plaintiff, : : v. : : HARVEY LEVY, SUBURBAN : THERAPY, INC., and : SUBURBAN MEDICAL ASSOCIATES, : : Defendants. : NO. 95-1674 M E M O R A N D U M Reed, J. January 16, 1998 The Court issues this memorandum in support of its Order dated January 9, 1998 (Document No. 42), in which the Court denied the motion of defendants Harvey Levy (“Levy”), Suburban Therapy, Inc. (“ST”), and Suburban Medical Associates (“SM”) (collectively “the defendants”) for partial reconsideration of the Order dated December 19, 1997 (Document No. 38) and granted in part the renewed motion of plaintiff Frank Fumai (“Fumai”) in limine to exclude all evidence and argument at trial that pertains or relates to the defendants’ claim or defense that Fumai breached a fiduciary duty owed to Allegheny United Hospitals (“Allegheny”) in connection with the sale of the assets of ST and SM to Allegheny (Document No. 37). I. BACKGROUND The following background facts are undisputed.1 On November 1, 1990, Fumai entered into an agreement with the defendants whereby Fumai would receive a commission from the sale of capital stock or assets of ST and SM if he procured a purchaser or introduced a party to the defendants who later introduced or procured a purchaser. Under the agreement, Fumai would receive 10% of the purchase price of ST and 5% of the purchase price of SM for such a sale. At the time of the contract between Fumai and the defendants, the main business of ST was the management of physician care services, including management of SM. -

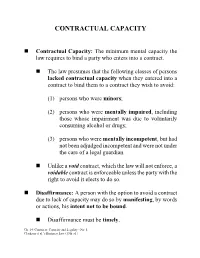

Contractual Capacity

CONTRACTUAL CAPACITY Contractual Capacity: The minimum mental capacity the law requires to bind a party who enters into a contract. The law presumes that the following classes of persons lacked contractual capacity when they entered into a contract to bind them to a contract they wish to avoid: (1) persons who were minors; (2) persons who were mentally impaired, including those whose impairment was due to voluntarily consuming alcohol or drugs; (3) persons who were mentally incompetent, but had not been adjudged incompetent and were not under the care of a legal guardian. Unlike a void contract, which the law will not enforce, a voidable contract is enforceable unless the party with the right to avoid it elects to do so. Disaffirmance: A person with the option to avoid a contract due to lack of capacity may do so by manifesting, by words or actions, his intent not to be bound. Disaffirmance must be timely. Ch. 14: Contracts: Capacity and Legality - No. 1 Clarkson et al.’s Business Law (13th ed.) MINORITY Subject to certain exceptions, an unmarried legal minor (in most states, someone less than 18 years old) may avoid a contract that would bind him if he were an adult. Contracts entered into by young children and contracts for something the law permits only for adults (e.g., a contract to purchase cigarettes or alcohol) are generally void, rather than voidable. Right to Disaffirm: Generally speaking, a minor may disaffirm a contract at any time during minority or for a reasonable time after he comes of age. When a minor disaffirms a contract, he can recover all property that he has transferred as consideration – even if it was subsequently transferred to a third party. -

Unit 6 – Contracts

Unit 6 – Contracts I. Definition A contract is a voluntary agreement between two or more parties that a court will enforce. The rights and obligations created by a contract apply only to the parties to the contract (i.e., those who agreed to them) and not to anyone else. II. Elements In order for a contract to be valid, certain elements must exist: (A) Competent parties. In order for a contract to be enforceable, the parties must have legal capacity. Even though most people can enter into binding agreements, there are some who must be protected from deception. The parties must be over the age of majority (18 under most state laws) and have sufficient mental capacity to understand the significance of the contract. Regarding the age requirement, if a minor enters a contract, that agreement can be voided by the minor but is binding on the other party, with some exceptions. (Contracts that a minor makes for necessaries such as food, clothing, shelter or transportation are generally enforceable.) This is called a voidable contract, which means that it will be valid (if all other elements are present) unless the minor wants to terminate it. The consequences of a minor avoiding a contract may be harsh to the other party. The minor need only return the subject matter of the contract to avoid the contract. if the subject matter of the contract is damaged the loss belongs to the nonavoiding party, not the minor. Regarding the mental capacity requirement, if the mental capacity of a party is so diminished that he cannot understand the nature and the consequences of the transaction, then that contract is also voidable (he can void it but the other party can not). -

Federalizing Contract Law

LCB_24_1_Article_5_Plass_Correction (Do Not Delete) 3/6/2020 10:06 AM FEDERALIZING CONTRACT LAW by Stephen A. Plass* Contract law is generally understood as state common law, supplemented by the Second Restatement of Contracts and Article 2 of the Uniform Commercial Code. It is regarded as an expression of personal liberty, anchored in the bar- gain and consideration model of the 19th century or classical period. However, for some time now, non-bargained or adhesion contracts have been the norm, and increasingly, the adjudication of legal rights and contractual remedies is controlled by privately determined arbitration rules. The widespread adoption of arbitral adjudication by businesses has been enthusiastically endorsed by the Supreme Court as consonant with the Federal Arbitration Act (“FAA”). How- ever, Court precedents have concluded that only bilateral or individualized arbitration promotes the goals of the FAA, while class arbitration is destruc- tive. Businesses and the Court have theorized that bilateral arbitration is an efficient process that reduces the transaction costs of all parties thereby permit- ting firms to reduce prices, create jobs, and innovate or improve products. But empirical research tells a different story. This Article discusses the constitu- tional contours of crafting common law for the FAA and its impact on state and federal laws. It shows that federal common law rules crafted for the FAA can operate to deny consumers and workers the neoclassical contractual guar- antee of a minimum adequate remedy and rob the federal and state govern- ments of billions of dollars in tax revenue. From FAA precedents the Article distills new rules of contract formation, interpretation, and enforcement and shows how these new rules undermine neoclassical limits on private control of legal remedies. -

Important Concepts in Contract

Munich Personal RePEc Archive Practical concepts in Contract Law Ehsan, zarrokh 14 August 2008 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/10077/ MPRA Paper No. 10077, posted 01 Jan 2009 09:21 UTC Practical concepts in Contract Law Author: EHSAN ZARROKH LL.M at university of Tehran E-mail: [email protected] TEL: 00989183395983 URL: http://www.zarrokh2007.20m.com Abstract A contract is a legally binding exchange of promises or agreement between parties that the law will enforce. Contract law is based on the Latin phrase pacta sunt servanda (literally, promises must be kept) [1]. Breach of a contract is recognised by the law and remedies can be provided. Almost everyone makes contracts everyday. Sometimes written contracts are required, e.g., when buying a house [2]. However the vast majority of contracts can be and are made orally, like buying a law text book, or a coffee at a shop. Contract law can be classified, as is habitual in civil law systems, as part of a general law of obligations (along with tort, unjust enrichment or restitution). Contractual formation Keywords: contract, important concepts, legal analyse, comparative. The Carbolic Smoke Ball offer, which bankrupted the Co. because it could not fulfill the terms it advertised In common law jurisdictions there are three key elements to the creation of a contract. These are offer and acceptance, consideration and an intention to create legal relations. In civil law systems the concept of consideration is not central. In addition, for some contracts formalities must be complied with under what is sometimes called a statute of frauds. -

Defense Counsel Journal April, 2000

Defense Counsel Journal April, 2000 Feature *209 WHAT'S HAPPENING TO THE PAROL EVIDENCE RULE? MORE HOLES IN THE DIKE Increasingly and alarmingly, parties face greater risks of losing their contractual bargains, no matter how unambiguous they may seem. Copyright © 2000 International Association of Defense Counsel; Mark O. Morris, Elizabeth Evensen I SAY to-mah-toe; you say to-ma-toe. Do we have a meeting of the minds? Should a court hear evidence to understand what we mean by "tomato?" It appears the same judicial trends that are making it easier and more lucrative to blame others in tort contexts now are invading the contractual arena to increase an unsatisfied party's chances of avoiding or altering unambiguous contractual obligations. Sanctity of contract has been a hallmark of American commerce. One of the guardians of this sanctity has been the parol evidence rule, which was developed to prevent contracting parties from trying to offer evidence to vary the terms of an unambiguous contract. Unfortunately, creative lawyers have persuaded some courts to effectively abandon the rule. The result is creating uncertainty in contractual relationships, turning contract interpretation into a sophomoric exercise that undermines expectations of certainty. CONTEXTUALISM V. TEXTUALISM A. General The rule derives its names from the French word parole, meaning a spoken or an oral word. This term has become a misnomer, however, because the rule now refers not only to oral, but also to written evidence. In addition, commentators agree that the rule is not a rule of evidence because it does not deal with a proper method of proving a question of fact. -

Contract Basics for Litigators: Illinois by Diane Cafferata and Allison Huebert, Quinn Emanuel Urquhart & Sullivan, LLP, with Practical Law Commercial Litigation

STATE Q&A Contract Basics for Litigators: Illinois by Diane Cafferata and Allison Huebert, Quinn Emanuel Urquhart & Sullivan, LLP, with Practical Law Commercial Litigation Status: Law stated as of 01 Jun 2020 | Jurisdiction: Illinois, United States This document is published by Practical Law and can be found at: us.practicallaw.tr.com/w-022-7463 Request a free trial and demonstration at: us.practicallaw.tr.com/about/freetrial A Q&A guide to state law on contract principles and breach of contract issues under Illinois common law. This guide addresses contract formation, types of contracts, general contract construction rules, how to alter and terminate contracts, and how courts interpret and enforce dispute resolution clauses. This guide also addresses the basics of a breach of contract action, including the elements of the claim, the statute of limitations, common defenses, and the types of remedies available to the non-breaching party. Contract Formation to enter into a bargain, made in a manner that justifies another party’s understanding that its assent to that 1. What are the elements of a valid contract bargain is invited and will conclude it” (First 38, LLC v. NM Project Co., 2015 IL App (1st) 142680-U, ¶ 51 (unpublished in your jurisdiction? order under Ill. S. Ct. R. 23) (citing Black’s Law Dictionary 1113 (8th ed.2004) and Restatement (Second) of In Illinois, the elements necessary for a valid contract are: Contracts § 24 (1981))). • An offer. • An acceptance. Acceptance • Consideration. Under Illinois law, an acceptance occurs if the party assented to the essential terms contained in the • Ascertainable Material terms. -

Rediscovering Subjectivity in Contracts: Adhesion and Unconscionability Richard L

Louisiana Law Review Volume 66 | Number 1 Fall 2005 Rediscovering Subjectivity in Contracts: Adhesion and Unconscionability Richard L. Barnes Repository Citation Richard L. Barnes, Rediscovering Subjectivity in Contracts: Adhesion and Unconscionability, 66 La. L. Rev. (2005) Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/lalrev/vol66/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at LSU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Louisiana Law Review by an authorized editor of LSU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Rediscovering Subjectivity in Contracts: Adhesion and Unconscionability * RichardL. Barnes The doctrines of adhesion and unconscionability owe their existence to the power of the libertarian model of bargaining. The premise of this Article is that the concept of objectivity has made adhesion and unconscionability doctrines of convenience, helpful in fine tuning the powerful concept of objectivity in that libertarian model. The conclusion reached is that both of these limiting doctrines are a product of the objective theory and serve complementary purposes. This Article asserts that the purpose of the doctrines of adhesion and unconscionability is to save the objective theory of contracts from troublesome over breadth. This Article begins with a description of the objective and subjective theories of contract enforceability. It will be shown that the traditional definition of contract as an objective bargain-in-fact' of the parties leaves too much to the imagination between the parties. Can individuals create a bargain for what is illegal? The libertarian answer would be yes, but the traditional objective doctrine hedges.