The Plains Garter Snake, Thamnophis Radix, in Ohio

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Survey for the Eastern Massasauga (Sistrurus C. Catenatus) in the Carlyle Lake Region

Survey for the Eastern Massasauga (Sistrurus c. catenatus) in the Carlyle Lake Region: Final Report for Summer 2003 – Spring 2004 Submitted to the: Illinois Department of Natural Resources In Fulfillment of DNR Contract Number R041000001 19 January 2005 Submitted by: Christopher A. Phillips and Michael J. Dreslik Illinois Natural History Survey Center for Biodiversity 607 East Peabody Drive Champaign, Illinois 61820 INTRODUCTION At the time of European settlement, the eastern massasauga (Sistrurus catenatus catenatus) was found throughout the northern two-thirds of Illinois. There are accounts of early travelers and farmers encountering 20 or more massasaugas in a single season (Hay, 1893). As early as 1866, however, the massasauga was noted as declining (Atkinson and Netting, 1927). Through subsequent years, habitat destruction and outright persecution reduced the Illinois range of the massasauga to a few widely scattered populations. Of the 24 localities Smith (1961) listed, only five may remain extant (Phillips et al., 1999a) and abundance estimates at all but one are less than 50 individuals (Anton, 1999; Wilson and Mauger, 1999). The exception is the Carlyle Lake population, where recent size estimates have exceeded 100 individuals (Phillips et al.,1999b; Ibid 2001). A cooperative effort between Scott Ballard of the Illinois Department of Natural Resources (IDNR) and site personnel at IDNR parks and Army Corps of Engineers (ACE) personnel at Carlyle Lake resulted in approximately 30 reports of the massasauga between 1991 and 1998 (S. Ballard, pers. com.). Most of these reports were associated with mowing and a few were the result of road mortality or incidental encounters with park personnel and visitors. -

Pit Vipers: from Fang to Needle—Three Critical Concepts for Clinicians

Tuesday, July 28, 2021 Pit Vipers: From Fang to Needle—Three Critical Concepts for Clinicians Keith J. Boesen, PharmD & Nicholas B. Hurst, M.D., MS Disclosures / Potential Conflicts of Interest • Keith Boesen and Nicholas Hurst are employed by Rare Disease Therapeutics, Inc. (RDT) • RDT is a U.S. company working with Laboratorios Silanes, S.A. de C.V., a company in Mexico • Laboratorios Silanes manufactures a variety of antivenoms Note: This program may contain the mention of suppliers, brands, products, services or drugs presented in a case study or comparative format using evidence-based research. Such examples are intended for educational and informational purposes and should not be perceived as an endorsement of any particular supplier, brand, product, service or drug. 2 Learning Objectives At the end of this session, participants should be able to: 1. Describe the venom variability in North American Pit Vipers 2. Evaluate the clinical symptoms associated with a North American Pit Viper envenomation 3. Develop a treatment plan for a North American Pit Viper envenomation 3 Audience Poll Question: #1 of 5 My level of expertise in treating Pit Viper Envenomation is… a. I wouldn’t know where to begin! b. I have seen a few cases… c. I know a thing or two because I’ve seen a thing or two d. I frequently treat these patients e. When it comes to Pit Viper envenomation, I am a Ssssuper Sssskilled Ssssnakebite Sssspecialist!!! 4 PIT VIPER ENVENOMATIONS PIT VIPERS Loreal Pits Movable Fangs 1. Russel 1983 -Photo provided by the Arizona Poison and Drug Information Center 1. -

FAMILY VIPERIDAE: VENOMOUS “Pit Vipers” Whose Fangs Fold up Against the Roof of Their Mouth, Such As Rattlesnakes, Copperheads, and Cottonmouths

FAMILY VIPERIDAE: VENOMOUS “pit vipers” whose fangs fold up against the roof of their mouth, such as rattlesnakes, copperheads, and cottonmouths COPPERHEAD—Agkistrodon contortrix Uncommon to common. Copperheads are found in wet wooded areas, high areas in swamps, and mountainous habitats, although they may be encountered occasionally in most terrestrial habitats. Adults usually are 2 to 3 ft. long. Their general appearance is light brown or pinkish with darker, saddle-shaped crossbands. The head is solid brown. Their leaf-pattern camouflage permits copperheads to be sit- Juvenile copper- heads and-wait predators, concealed not only from their prey but also from their enemies. Copperheads feed on mice, small birds, lizards, snakes, amphibians, and insects, especially cicadas. Like young cottonmouths, baby copperheads have a bright yellow tail that is used to lure small prey animals. 0123ft. Heat-sensing “pit” characteristic of pit vipers CANEBRAKE OR TIMBER RATTLESNAKE—Crotalus horridus Mountain form Common. This species occupies a wide diversity of terrestrial habitats, but is found most frequently in deciduous forests and high ground in swamps. Heavy-bodied adults are usually 3 to 4, and occasionally 5, ft. long. Their basic color is gray with black crossbands that usually are chevron-shaped. Timber rattlesnakes feed on various rodents, rabbits, and occasionally birds. These rattlesnakes are generally passive if not disturbed or pestered in some way. When a rattlesnake is Coastal plain form encountered, the safest reaction is to back away--it will not try to attack you if you leave it alone. 012345 ft. EASTERN DIAMONDBACK RATTLESNAKE— Crotalus adamanteus Rare. This rattlesnake is found in both wet and dry terrestrial habitats including palmetto stands, pine woods, and swamp margins. -

Reptiles of Alberta

of Alberta 2 Alberta Conservation Association - Reptiles of Alberta How Can I Help Alberta’s Reptiles? Like many other wildlife species, Alberta’s reptiles struggle to adapt to human impacts on the habitats and ecosystems in which they depend. The destruction and exploitation of natural habitats is causing reptiles to become rare or to disappear from many areas. Chemicals and poisons introduced into their ecosystems harms them directly or indirectly by affecting their food supply. Development and urbanization not only contribute to an increase in road mortality, pollution, and loss of habitat, but also human-snake conflicts that often end unjustly with the demise of snakes. The key to preserving Alberta’s reptiles is to conserve the places where they live. Actively managing the health and function of ecosystems, preserving native habitats, and avoiding the use of pesticides and other harmful chemicals can result in wide-ranging benefits for both reptiles and people alike. While traveling on Alberta roadways be mindful of snakes that may be attracted to warm road surfaces or that may be crossing during their wanderings. Keep a careful lookout for “snake crossing” signs that warn motorists of the possible presence of snakes on roadways in key areas. Perhaps one of the easiest things you can do to help Alberta’s reptiles is sharing what you have learned in this brochure with others, and when it comes to snakes, being more tolerant. What is a Reptile? Reptiles have been around for some 300 million years and date back to the age of the dinosaur. That era has long past and those giants have disappeared, but more than 8000 species of reptiles still thrive today! Snakes, lizards, and turtles are all reptiles. -

Snakes of the Prairie

National Park Service Scotts Bluff U.S. Department of the Interior Scotts Bluff National Monument Nebraska Snakes of the Prairie Wildlife and Scotts Bluff National Monument is a unique historic landmark which preserves both cultural and Landscapes natural resources. Sweeping from the river valley woodlands, to the mixed-grass prairie, to pine studded bluffs, Scotts Bluff contains a wide variety of wildlife and landscapes. The 3,000 acres com- prising Scotts Bluff conserves one of the last areas of the Great Plains which has not been significant- ly changed by human occupation. Biological Four different species of snakes are known to live at Scotts Bluff National Monument, and may be Diversity of seen by park visitors during the warm months of the year. Though many people regard these rep- the Prairie tiles with feelings of fear and loathing, snakes are generally undeserving of their bad reputation. All snakes are exclusively carniverous and often feed on rodents and insects and should be considered beneficial to humans. They are cold-blooded animals and must avoid extremes of heat and cold. For this reason, you are unlikely to see snakes in the open on hot summer days. If a snake of any kind is encountered, the best advice is to give it plenty of room and a chance to escape. All snakes avoid humans whenever possible and should not be provoked. Prairie Rattlesnake Photo by Steve Thompson Prairie Rattlesnake (Crotalus viridis viridis) The prairie rattlesnake is the only venomous snake found at Scotts Bluff National Monument. Rat- tlesnakes belong to the Pit Viper family of snakes, characterized by temperature sensitive “pits” on either side of the face between the eye and the nostril. -

Reptile and Amphibian Enforcement Applicable Law Sections

Reptile and Amphibian Enforcement Applicable Law Sections Environmental Conservation Law 11-0103. Definitions. As used in the Fish and Wildlife Law: 1. a. "Fish" means all varieties of the super-class Pisces. b. "Food fish" means all species of edible fish and squid (cephalopoda). c. "Migratory fish of the sea" means both catadromous and anadromous species of fish which live a part of their life span in salt water streams and oceans. d. "Fish protected by law" means fish protected, by law or by regulations of the department, by restrictions on open seasons or on size of fish that may be taken. e. Unless otherwise indicated, "Trout" includes brook trout, brown trout, red-throat trout, rainbow trout and splake. "Trout", "landlocked salmon", "black bass", "pickerel", "pike", and "walleye" mean respectively, the fish or groups of fish identified by those names, with or without one or more other common names of fish belonging to the group. "Pacific salmon" means coho salmon, chinook salmon and pink salmon. 2. "Game" is classified as (a) game birds; (b) big game; (c) small game. a. "Game birds" are classified as (1) migratory game birds and (2) upland game birds. (1) "Migratory game birds" means the Anatidae or waterfowl, commonly known as geese, brant, swans and river and sea ducks; the Rallidae, commonly known as rails, American coots, mud hens and gallinules; the Limicolae or shorebirds, commonly known as woodcock, snipe, plover, surfbirds, sandpipers, tattlers and curlews; the Corvidae, commonly known as jays, crows and magpies. (2) "Upland game birds" (Gallinae) means wild turkeys, grouse, pheasant, Hungarian or European gray-legged partridge and quail. -

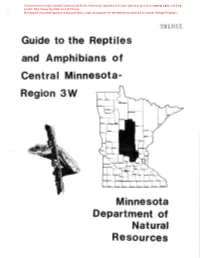

Guide to the Reptil and Am Hibians of Central Minnesota- Regi N3w

This document is made available electronically by the Minnesota Legislative Reference Library as part of an ongoing digital archiving project. http://www.leg.state.mn.us/lrl/lrl.asp (Funding for document digitization was provided, in part, by a grant from the Minnesota Historical & Cultural Heritage Program.) Guide to the Reptil and Am hibians of Central Minnesota- Regi n3W Minnesota Department of Natural Resources January 1, 1979 Guide to the Herpetofauna of Central Minnesota Region 3 - West This preliminary guide has been prepared as a reference to the occurrence and distribution of reptiles and amphibians of Region 3 - West in Central Minnesota. Taxonomy and identification are based on "A Field Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians" by Roger Conant (Second Edition 1975). Figure 1 is a map of the region. Counties Included: Benton, Cass, Crow Wing, Morrison, Sherburne, Stearns, Todd, Wadena and Wright. SPECIES LIST Turtles Salamanders Common snapping turtle Blue-spotted salamander Map turtle Eastern tiger salamander Western painted turtle Mudpuppy (?) *Blanding's turtle *Central (Common) newt (?) Western spiny softshell *Red-backed salamander (?) Lizards Toads Northern priaire skink American toad Snakes Frogs Red-bellied snake Northern spring peeper Texas brown (DeKay's) snake Common (gray) treefrog Northern water snake Boreal chorus frog J s.s. Western plains garter snake Western chorus frog Red-sided garter snake] s.s. Mink frog Eastern garter snake Northern leopard frog Eastern hognose snake Green frog *Western smooth green snake} s.s. Wood frog *Eastern smooth green snake Bull snake s.s. - single species (?) - hypothetical species - reports needed * - special interest species - reports needed Summary A total of 24 species are found in Region 3 - West. -

Eastern Massasauga Natural Diversity Section June 2011

Species Action Plan Eastern Massasauga Natural Diversity Section June 2011 Species Action Plan: Eastern Massasauga (Sistrurus catenatus catenatus) Purpose: This plan provides an initial five year blueprint for the actions needed to attain near-term and, ultimately, long-term goals for the conservation and recovery of the eastern massasauga. The action plan is Figure 1. Eastern Massasauga (Sistrurus a living document and will be updated as catenatus). Photo-Charlie Eichelberger. needed to reflect progress toward those goals and to incorporate new information as it becomes available. Description: A small, stout-bodied rattlesnake. The body is patterned with a Goals: The immediate goal is to maintain series of large, dark brown, mid-dorsal the extant populations of eastern blotches and two to three rows of lateral massasauaga in the Commonwealth and to blotches set upon a light gray or tan protect its remaining habitat. The ground color. The tail has three to six dark secondary goal is to enhance extant cross-bands. The venter is typically black. populations by improving and increasing Neonates have the same pattern and local habitat. The long-term recovery goal coloration as adults, with the exception of is to increase viable, reproducing the neonate exhibiting a yellow tip at the populations in extant and historic locations proximate end of the tail. At birth, S. c. with the possibility of removal of the catenatus average 23.6 cm in total length species from the Pennsylvania list of (Reinert, 1981) and have a single rattle endangered species (58 Pa. Code §75.1). segment (button) at the tip of their tail. -

Western Massasauga ( ЛХЦФЧФЧХ ЦЗФЙЗПЛРЧХ)

Western Massasauga (Sistrurus tergeminus ) A Species Conservation Assessment for The Nebraska Natural Legacy Project Prepared by Melissa J. Panella and Brent D. Johnson for Nebraska Game and Parks Commission Wildlife Division Lincoln, Nebraska June 2014 The mission of the Nebraska Natural Legacy Project is to implement a blueprint for conserving Nebraska’s flora, fauna and natural habitats through the proactive, voluntary conservation actions of partners, communities and individuals. Purpose The primary goal in development of at-risk species conservation assessments is to compile biological and ecological information that may assist conservation practitioners in making decisions regarding the conservation of species of interest. The Nebraska Natural Legacy Project recognizes the Western Massasauga ( Sistrurus tergeminus ) as a Tier I at-risk species. Provided are some general management recommendations regarding Western Massasaugas. Conservation practitioners will need to use professional judgment to make specific management decisions based on objectives, location, and a multitude of variables. This resource was designed to share available knowledge of this at-risk species that will aid in the decision-making process or in identifying research needs to benefit the species. Species conservation assessments will need to be updated as relevant scientific information becomes available and/or conditions change. Though the Nebraska Natural Legacy Project focuses efforts in the state’s Biologically Unique Landscapes, it is recommended that whenever possible, practitioners make considerations for a species throughout its range in order to increase the outcome of successful conservation efforts. And in the case of conservation for massasaugas, it is particularly necessary to take into account the seasonal needs of the species and conserve both wintering and summer foraging habitat. -

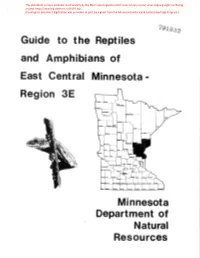

Guide and East Regi T . the Reptiles Mphibians of Minnesota

This document is made available electronically by the Minnesota Legislative Reference Library as part of an ongoing digital archiving project. http://www.leg.state.mn.us/lrl/lrl.asp (Funding for document digitization was provided, in part, by a grant from the Minnesota Historical & Cultural Heritage Program.) Guide t . the Reptiles and mphibians of East Minnesota - Regi n 3E Minnesota Department of Natural Resources January 1, 1979 Guide to the Herpetofauna of Central Minnesota Region 3 - East This preliminary guid~ has been prepared as· a reference to the occurrence and distribution of reptiles and amphibians of Region 3 - East in Central Minnesota. Taxonomy and identification are based on 11 A Field Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians" by Roger Conant {Second Edition, 1975). Figure 1 is a map of this region. Counties Included: Chisago, Isanti, Kanabec, Mille Lacs, and Pine. SPECIES LIST Turtles Salamanders Common snapping turtle Blue-spotted salamander *Wood turtle Eastern tiger salamander Map turtle *Red-backed salamander Western painted turtle Mudpuppy {?) *Blanding's turtle *Central {Common) newt {?) Western spiny softshell *Four-toed salamander (?) Lizards Toads Northern prairie skink American toad *Five-lined (blue-tailed) skink (?) Frogs Snakes Northern spring peeper Red-bellied snake Gray (Common) treefrog Northern water snake Boreal chorus frog J Western plains garter snake Western chorus frog s.s. Eastern garter snake J s.s. Mink.frog Red-sided garter snake {?) Northern leopard frog Eastern hognose snake Green frog *Western smooth green snakeJ s.s. Wood frog * Eastern smoot h green sna ke Bull snake Western fox snake Eastern milk snake s.s. - single species (?) - hypothetical species - reports needed * - special interest species - reports needed Summary A total of 27 species have been recorded in Region 3 - East. -

Desert Massasauga Rattlesnake (Sistrurus Catenatus Edwardsii): a Technical Conservation Assessment

Desert Massasauga Rattlesnake (Sistrurus catenatus edwardsii): A Technical Conservation Assessment Prepared for the USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region, Species Conservation Project December 12, 2005 Stephen P. Mackessy, Ph.D.1 with input from Douglas A. Keinath2, Mathew McGee2, Dr. David McDonald3, and Takeshi Ise3 1 School of Biological Sciences, University of Northern Colorado, 501 20th St., CB 92, Greeley, CO 80639-0017 2 Wyoming Natural Diversity Database, University of Wyoming, P.O. Box 3381, Laramie, WY 82071 3 Department of Zoology and Physiology, University of Wyoming, P.O. Box 3166, Laramie, WY 82071 Peer Review Administered by Society for Conservation Biology Mackessy, S.P. (2005, December 12). Desert Massasauga Rattlesnake (Sistrurus catenatus edwardsii): a technical conservation assessment. [Online]. USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region. Available: http:// www.fs.fed.us/r2/projects/scp/assessments/massasauga.pdf [date of access]. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS We would like to thank the members of the massasauga listserv for information provided, including but not limited to Tom Anton, Gary Casper, Frank Durbian, Andrew Holycross, Rebecca Key, David Mauger, Jennifer Szymanski, and Darlene Upton. For excellent field work on surveys of southeastern Colorado and radiotelemetry of desert massasaugas, the lead author thanks Enoch Bergman, Ron Donoho, Ben Hill, Justin Hobert, Rocky Manzer, Chad Montgomery, James Siefert, Kevin Waldron, and Andrew Wastell. John Palmer and the Palmer family generously provided access to their ranch, which was critical for both survey and telemetry work, and many other kindnesses. For discussions about massasaugas at various times, I thank David Chiszar, Harry Greene, Geoff Hammerson, Andrew Holycross, Lauren Livo, Richard Seigel, and Hobart M. -

Tan Choo Hock Thesis Submitted in Fulfi

TOXINOLOGICAL CHARACTERIZATIONS OF THE VENOM OF HUMP-NOSED PIT VIPER (HYPNALE HYPNALE) TAN CHOO HOCK THESIS SUBMITTED IN FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY FACULTY OF MEDICINE UNIVERSITY OF MALAYA KUALA LUMPUR 2013 Abstract Hump-nosed pit viper (Hypnale hypnale) is a medically important snake in Sri Lanka and Western Ghats of India. Envenomation by this snake still lacks effective antivenom clinically. The species is also often misidentified, resulting in inappropriate treatment. The median lethal dose (LD50) of H. hypnale venom varies from 0.9 µg/g intravenously to 13.7 µg/g intramuscularly in mice. The venom shows procoagulant, hemorrhagic, necrotic, and various enzymatic activities including those of proteases, phospholipases A2 and L-amino acid oxidases which have been partially purified. The monovalent Malayan pit viper antivenom and Hemato polyvalent antivenom (HPA) from Thailand effectively cross-neutralized the venom’s lethality in vitro (median effective dose, ED50 = 0.89 and 1.52 mg venom/mL antivenom, respectively) and in vivo in mice, besides the procoagulant, hemorrhagic and necrotic effects. HPA also prevented acute kidney injury in mice following experimental envenomation. Therefore, HPA may be beneficial in the treatment of H. hypnale envenomation. H. hypnale-specific antiserum and IgG, produced from immunization in rabbits, effectively neutralized the venom’s lethality and various toxicities, indicating the feasibility to produce an effective specific antivenom with a common immunization regime. On indirect ELISA, the IgG cross-reacted extensively with Asiatic crotalid venoms, particularly that of Calloselasma rhodostoma (73.6%), suggesting that the two phylogenically related snakes share similar venoms antigenic properties.