Desert Massasauga Rattlesnake (Sistrurus Catenatus Edwardsii): a Technical Conservation Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What You Should Know About Rattlesnakes

Rattlesnakes in The Rattlesnakes of Snake Bite: First Aid WHAT San Diego County Parks San Diego County The primary purpose of the rattlesnake’s venomous bite is to assist the reptile in securing The Rattlesnake is an important natural • Colorado Desert Sidewinder its prey. After using its specialized senses to find YOU SHOULD element in the population control of small (Crotalus cerastes laterorepens) its next meal, the rattlesnake injects its victim mammals. Nearly all of its diet consists of Found only in the desert, the sidewinder prefers with a fatal dose of venom. animals such as mice and rats. Because they are sandy flats and washes. Its colors are those of KNOW ABOUT so beneficial, rattlesnakes are fully protected the desert; a cream or light brown ground color, To prevent being bitten, the best advice is to leave within county parks. with a row of brown blotches down the middle snakes alone. RATTLESNAKES If you encounter a rattlesnake while hiking, of the back. A hornlike projection over each eye Most bites occur when consider yourself lucky to have seen one of separates this rattlesnake from the others in our area. Length: 7 inches to 2.5 feet. someone is nature’s most interesting animals. If you see a trying to pick rattlesnake at a campsite or picnic area, please up a snake, inform the park rangers. They will do their best • Southwestern Speckled Rattlesnake (Crotalus mitchelli pyrrhus) tease it, or kill to relocate the snake. it. If snakes are Most often found in rocky foothill areas along the provided an coast or in the desert. -

The Timber Rattlesnake: Pennsylvania’S Uncanny Mountain Denizen

The Timber Rattlesnake: Pennsylvania’s Uncanny Mountain Denizen photo-Steve Shaffer by Christopher A. Urban breath, “the only good snake is a dead snake.” Others are Chief, Natural Diversity Section fascinated or drawn to the critter for its perceived danger- ous appeal or unusual size compared to other Pennsylva- Who would think that in one of the most populated nia snakes. If left unprovoked, the timber rattlesnake is states in the eastern U.S., you could find a rattlesnake in actually one of Pennsylvania’s more timid and docile the mountains of Penn’s Woods? As it turns out, most snake species, striking only when cornered or threatened. timber rattlesnakes in Pennsylvania are found on public Needless to say, the Pennsylvania timber rattlesnake is an land above 1,800 feet elevation. Of the three venomous intriguing critter of Pennsylvania’s wilderness. snakes that occur in Pennsylvania, most people have heard about this one. It strikes fear in the hearts of some Description and elicits fascination in others. When the word “rattler” The timber rattlesnake (Crotalus horridus) is a large comes up, you may hear some folks grumble under their (up to 74 inches), heavy-bodied snake of the pit viper www.fish.state.pa.us Pennsylvania Angler & Boater, January-February 2004 17 family (Viperidae). This snake has transverse “V”-shaped or chevronlike dark bands on a gray, yellow, black or brown body color. The tail is completely black with a rattle. The head is large, flat and triangular, with two thermal-sensitive pits between the eyes and the nostrils. The timber rattlesnake’s head color has two distinct color phases. -

Survey for the Eastern Massasauga (Sistrurus C. Catenatus) in the Carlyle Lake Region

Survey for the Eastern Massasauga (Sistrurus c. catenatus) in the Carlyle Lake Region: Final Report for Summer 2003 – Spring 2004 Submitted to the: Illinois Department of Natural Resources In Fulfillment of DNR Contract Number R041000001 19 January 2005 Submitted by: Christopher A. Phillips and Michael J. Dreslik Illinois Natural History Survey Center for Biodiversity 607 East Peabody Drive Champaign, Illinois 61820 INTRODUCTION At the time of European settlement, the eastern massasauga (Sistrurus catenatus catenatus) was found throughout the northern two-thirds of Illinois. There are accounts of early travelers and farmers encountering 20 or more massasaugas in a single season (Hay, 1893). As early as 1866, however, the massasauga was noted as declining (Atkinson and Netting, 1927). Through subsequent years, habitat destruction and outright persecution reduced the Illinois range of the massasauga to a few widely scattered populations. Of the 24 localities Smith (1961) listed, only five may remain extant (Phillips et al., 1999a) and abundance estimates at all but one are less than 50 individuals (Anton, 1999; Wilson and Mauger, 1999). The exception is the Carlyle Lake population, where recent size estimates have exceeded 100 individuals (Phillips et al.,1999b; Ibid 2001). A cooperative effort between Scott Ballard of the Illinois Department of Natural Resources (IDNR) and site personnel at IDNR parks and Army Corps of Engineers (ACE) personnel at Carlyle Lake resulted in approximately 30 reports of the massasauga between 1991 and 1998 (S. Ballard, pers. com.). Most of these reports were associated with mowing and a few were the result of road mortality or incidental encounters with park personnel and visitors. -

Venomous Snakes in Pennsylvania the First Question Most People Ask When They See a Snake Is “Is That Snake Poisonous?” Technically, No Snake Is Poisonous

Venomous Snakes in Pennsylvania The first question most people ask when they see a snake is “Is that snake poisonous?” Technically, no snake is poisonous. A plant or animal that is poisonous is toxic when eaten or absorbed through the skin. A snake’s venom is injected, so snakes are classified as venomous or nonvenomous. In Pennsylvania, we have only three species of venomous snakes. They all belong to the pit viper Nostril family. A snake that is a pit viper has a deep pit on each side of its head that it uses to detect the warmth of nearby prey. This helps the snake locate food, especially when hunting in the darkness of night. These Pit pits can be seen between the eyes and nostrils. In Pennsylvania, Pennsylvania Snakes all of our venomous Checklist snakes have slit-like A complete list of Pennsylvania’s pupils that are 21 species of snakes. similar to a cat’s eye. Venomous Nonvenomous Copperhead (venomous) Nonvenomous snakes Eastern Garter Snake have round pupils, like a human eye. Eastern Hognose Snake Eastern Massasauga (venomous) Venomous If you find a shedded snake Eastern Milk Snake skin, look at the scales on the Eastern Rat Snake underside. If they are in a single Eastern Ribbon Snake Eastern Smooth Earth Snake row all the way to the tip of its Eastern Worm Snake tail, it came from a venomous snake. Kirtland’s Snake If the scales split into a double row Mountain Earth Snake at the tail, the shedded skin is from a Northern Black Racer Nonvenomous nonvenomous snake. -

Ecology of the Desert Massasauga Rattlesnake in Colorado: Habitat and Resource Utilization

Ecology of the Desert Massasauga Rattlesnake in Colorado: Habitat and Resource Utilization A report to the CDOW and USFWS for the Colorado Wildlife Conservation Grant Program Dr. Stephen P. Mackessy School of Biological Sciences University of Northern Colorado 501 20th St., CB 92 Greeley, CO 80639-0017 USA Tel: (970)-351-2429 Fax: (970)-351-2335 Email: [email protected] http://www.unco.edu/nhs/biology/faculty_staff/mackessy_stephen.htm Desert Massasauga (Sistrurus catenatus edwardsii) from Lincoln County, Colorado ABSTRACT We conducted a radiotelemetric study on a population of Desert Massasaugas (Sistrurus catenatus edwardsii) in Lincoln County, SE Colorado. Massasaugas were most active between 14 and 30 °C, with an average ambient temperature during activity of 22.1°C. In the spring, snakes make long distance movements (up to 2 km) from the hibernaculum (shortgrass, compacted clay soils) to summer foraging areas (mixed grass/sandsage, sand hills). Summer activity is characterized by short distance movements, and snakes are most often observed at the base of sandsage in ambush or resting coils. Massasaugas gave birth to 5-7 young in late August, and reproduction appears to be biennial. Observations on three radioed gravid females indicated that Desert Massasaugas show maternal attendance for at least five days post-parturition. Snakes returned to the hibernaculum area in October and appear to hibernate individually in rodent burrows most commonly. However, the immediate region is utilized by several other species of snakes, particularly Prairie Rattlesnakes (Crotalus viridis viridis), and Massasaugas were also observed at the entrance to these den sites, suggesting that they are used by the Massasaugas as well. -

The Plains Garter Snake, Thamnophis Radix, in Ohio

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications from the Harold W. Manter Laboratory of Parasitology Parasitology, Harold W. Manter Laboratory of 6-30-1945 The Plains Garter Snake, Thamnophis radix, in Ohio Roger Conant Zoological Society of Philadelphia Edward S. Thomas Ohio State Museum Robert L. Rausch University of Washington, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/parasitologyfacpubs Part of the Parasitology Commons Conant, Roger; Thomas, Edward S.; and Rausch, Robert L., "The Plains Garter Snake, Thamnophis radix, in Ohio" (1945). Faculty Publications from the Harold W. Manter Laboratory of Parasitology. 378. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/parasitologyfacpubs/378 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Parasitology, Harold W. Manter Laboratory of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications from the Harold W. Manter Laboratory of Parasitology by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. 1945, NO.2 COPEIA June 30 The Plains Garter Snake, Thamnophis radix, in Ohio By ROGER CONANT, EDWARD S. THOMAS, and ROBERT L. RAUSCH HE announcement that Thamnophis radix, the plains garter snake, oc T curs in Ohio and is not rare in at least one county, will surprise most herpetologists and students of animal distribution. Since the publication of Ruthven's monograph on the genus (1908), almost all authors have followed his definition of the range of this species, giving eastern Illinois as its eastern most limit. Ruthven (po 80), however, believed that radix very probably would be found in western Indiana, a supposition since substantiated by Schmidt and Necker (1935: 72), who report the species from the dune region of Lake and Porter counties. -

Agkistrodon Piscivorus)

BearWorks MSU Graduate Theses Fall 2019 Behavioral Aspects Of Chemoreception In Juvenile Cottonmouths (Agkistrodon Piscivorus) Chelsea E. Martin Missouri State University, [email protected] As with any intellectual project, the content and views expressed in this thesis may be considered objectionable by some readers. However, this student-scholar’s work has been judged to have academic value by the student’s thesis committee members trained in the discipline. The content and views expressed in this thesis are those of the student-scholar and are not endorsed by Missouri State University, its Graduate College, or its employees. Follow this and additional works at: https://bearworks.missouristate.edu/theses Part of the Behavior and Ethology Commons Recommended Citation Martin, Chelsea E., "Behavioral Aspects Of Chemoreception In Juvenile Cottonmouths (Agkistrodon Piscivorus)" (2019). MSU Graduate Theses. 3466. https://bearworks.missouristate.edu/theses/3466 This article or document was made available through BearWorks, the institutional repository of Missouri State University. The work contained in it may be protected by copyright and require permission of the copyright holder for reuse or redistribution. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BEHAVIORAL ASPECTS OF CHEMORECEPTION IN JUVENILE COTTONMOUTHS (AGKISTRODON PISCIVORUS) A Master’s Thesis Presented to The Graduate College of Missouri State University TEMPLATE In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science, Biology By Chelsea E. Martin December 2019 Copyright 2019 by Chelsea Elizabeth Martin ii BEHAVIORAL ASPECTS OF CHEMORECPTION IN JUVENILE COTTONMOUTHS (AGKISTRODON PISCIVORUS) Biology Missouri State University, December 2019 Master of Science Chelsea E. Martin ABSTRACT For snakes, chemical recognition of predators, prey, and conspecifics has important ecological consequences. -

Avoiding and Treating Timber Rattlesnake Bites Updated 2020

Avoiding and Treating Timber Rattlesnake Bites Updated 2020 Timber rattlesnakes live in the blufflands of southeastern Minnesota. They are not found anywhere else in the state. They can be distinguished from nonvenomous snakes by a pronounced off white rattle at the end of a black tail; by their head, which is solid brown/tan, triangular shaped, and noticeably larger than their slender neck; and by the dark, black bands or chevrons running across their body. The bands often resemble the black stripe on the cartoon character Charlie Brown’s shirt. The question that often arises when the word rattlesnake comes up is, “What if one bites me?” The likelihood of being bitten by a rattlesnake is quite small. Timber rattlesnakes are generally very docile snakes and typically bite as a last resort. Instead, its instincts are to avoid danger by retreating to cover or by hiding using its camouflage coloration to blend into its surroundings. If cornered and provoked, a timber rattlesnake may respond aggressively. It will usually rattle its tail to let you know it is getting agitated. The snake may even puff itself up to appear bigger. Upon further provocation, the snake may bluff strike, where it lunges out, but doesn’t open its mouth or it may strike with an open mouth. Because venom is costly for a rattlesnake to produce, and you are not considered food, a snake often will not actively inject venom when it bites. In fact, nearly half of all timber rattlesnake bites to humans contain little to no venom, commonly referred to as dry or medically insignificant bites. -

Xenosaurus Tzacualtipantecus. the Zacualtipán Knob-Scaled Lizard Is Endemic to the Sierra Madre Oriental of Eastern Mexico

Xenosaurus tzacualtipantecus. The Zacualtipán knob-scaled lizard is endemic to the Sierra Madre Oriental of eastern Mexico. This medium-large lizard (female holotype measures 188 mm in total length) is known only from the vicinity of the type locality in eastern Hidalgo, at an elevation of 1,900 m in pine-oak forest, and a nearby locality at 2,000 m in northern Veracruz (Woolrich- Piña and Smith 2012). Xenosaurus tzacualtipantecus is thought to belong to the northern clade of the genus, which also contains X. newmanorum and X. platyceps (Bhullar 2011). As with its congeners, X. tzacualtipantecus is an inhabitant of crevices in limestone rocks. This species consumes beetles and lepidopteran larvae and gives birth to living young. The habitat of this lizard in the vicinity of the type locality is being deforested, and people in nearby towns have created an open garbage dump in this area. We determined its EVS as 17, in the middle of the high vulnerability category (see text for explanation), and its status by the IUCN and SEMAR- NAT presently are undetermined. This newly described endemic species is one of nine known species in the monogeneric family Xenosauridae, which is endemic to northern Mesoamerica (Mexico from Tamaulipas to Chiapas and into the montane portions of Alta Verapaz, Guatemala). All but one of these nine species is endemic to Mexico. Photo by Christian Berriozabal-Islas. Amphib. Reptile Conserv. | http://redlist-ARC.org 01 June 2013 | Volume 7 | Number 1 | e61 Copyright: © 2013 Wilson et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Com- mons Attribution–NonCommercial–NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License, which permits unrestricted use for non-com- Amphibian & Reptile Conservation 7(1): 1–47. -

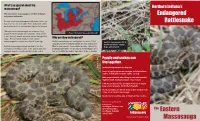

The Eastern Massasauga Rattlesnake Is Toxic, but Only a Small Amount Is Injected Through Short Fangs

What’s so special about the massasauga? Northern Indiana’s The rare eastern massasauga is northern Indiana’s only native rattlesnake. Endangered Because eastern massasaugas are shy and secretive, you may never see one in the wild. These snakes hide under Rattlesnake brush and retreat to a sheltered area if spotted in the open. Although eastern massasaugas are venomous, they usually flee from humans rather than bite. Their venom Range of the Eastern Massasauga Rattlesnake is toxic, but only a small amount is injected through short fangs. The last human fatality from an eastern Why are they endangered? massasauga bite occurred more than 60 years ago. Eastern massasaugas are endangered over much of their Eastern massasaugas live in range because their wetland habitats are often drained and northern Indiana’s swamps, Eastern massasaugas play an important role in the filled for development. These snakes are also collected for bogs, and wetlands. ecosystem by feeding on mice, voles, and shrews, thus the illegal reptile trade. People may kill massasaugas out of Christopher Smith helping to keep the rodent population under control. fear, not realizing the snakes’ importance to the ecosystem. People and snakes can live together. Nicholas Scobel Understanding snakes is the first step. Learn to identify eastern massasaugas and other Indiana snakes. A field guide to native reptiles can help. Wear proper footwear when hiking in areas where snakes might be found, especially at night. Stay on trails. Limit the use of pesticides and other chemicals on natural areas on your property. All wildlife will benefit. Teach your family and friends about snakes and what to do if they see an eastern massasauga. -

Species Assessment for the Midget Faded Rattlesnake (Crotalus Viridis Concolor)

SPECIES ASSESSMENT FOR THE MIDGET FADED RATTLESNAKE (CROTALUS VIRIDIS CONCOLOR ) IN WYOMING prepared by 1 2 AMBER TRAVSKY AND DR. GARY P. BEAUVAIS 1 Real West Natural Resource Consulting, 1116 Albin Street, Laramie, WY 82072; (307) 742-3506 2 Director, Wyoming Natural Diversity Database, University of Wyoming, Dept. 3381, 1000 E. University Ave., Laramie, WY 82071; (307) 766-3023 prepared for United States Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management Wyoming State Office Cheyenne, Wyoming October 2004 Travsky and Beauvais – Crotalus viridus concolor October 2004 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................. 2 NATURAL HISTORY ........................................................................................................................... 2 Morphological Description........................................................................................................... 3 Taxonomy and Distribution ......................................................................................................... 4 Habitat Requirements ................................................................................................................. 6 General ............................................................................................................................................6 Area Requirements..........................................................................................................................7 -

Pit Vipers: from Fang to Needle—Three Critical Concepts for Clinicians

Tuesday, July 28, 2021 Pit Vipers: From Fang to Needle—Three Critical Concepts for Clinicians Keith J. Boesen, PharmD & Nicholas B. Hurst, M.D., MS Disclosures / Potential Conflicts of Interest • Keith Boesen and Nicholas Hurst are employed by Rare Disease Therapeutics, Inc. (RDT) • RDT is a U.S. company working with Laboratorios Silanes, S.A. de C.V., a company in Mexico • Laboratorios Silanes manufactures a variety of antivenoms Note: This program may contain the mention of suppliers, brands, products, services or drugs presented in a case study or comparative format using evidence-based research. Such examples are intended for educational and informational purposes and should not be perceived as an endorsement of any particular supplier, brand, product, service or drug. 2 Learning Objectives At the end of this session, participants should be able to: 1. Describe the venom variability in North American Pit Vipers 2. Evaluate the clinical symptoms associated with a North American Pit Viper envenomation 3. Develop a treatment plan for a North American Pit Viper envenomation 3 Audience Poll Question: #1 of 5 My level of expertise in treating Pit Viper Envenomation is… a. I wouldn’t know where to begin! b. I have seen a few cases… c. I know a thing or two because I’ve seen a thing or two d. I frequently treat these patients e. When it comes to Pit Viper envenomation, I am a Ssssuper Sssskilled Ssssnakebite Sssspecialist!!! 4 PIT VIPER ENVENOMATIONS PIT VIPERS Loreal Pits Movable Fangs 1. Russel 1983 -Photo provided by the Arizona Poison and Drug Information Center 1.