Military Law Review, Vol. 57

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Legal Advisers in Armed Forces

ADVISORY SERVICE ON INTERNATIONAL HUMANITARIAN LAW ____________________________________ Legal advisers in armed forces By ratifying the Geneva Conventions of 1949 and their Additional Protocols of 1977, a State commits itself to respecting and ensuring respect for these international legal instruments in all circumstances. Knowledge of the law is an essential precondition for its proper application. The aim of requiring legal advisers in the armed forces, as stipulated in Article. 82 of Additional Protocol I, is to improve knowledge of – and hence compliance with – international humanitarian law. As the conduct of hostilities was becoming increasingly complex, both legally and technically, the States considered it appropriate when negotiating Additional Protocol I to provide military commanders with legal advisers to help them apply and teach international humanitarian law. An obligation for States and for provisions of international humanitarian law if they are to parties to conflict humanitarian law as widely as advise military commanders possible, in particular by including effectively. “The High Contracting Parties at all the study of this branch of law in times, and the Parties to the conflict their military training programmes. This obligation is analogous to that in time of armed conflict, shall contained in Article 6 of the same ensure that legal advisers are protocol (Qualified persons), under available, when necessary, to The role of the legal adviser which the States Parties must advise military commanders at the endeavour to train qualified appropriate level on the application Article 82 gives a flexible definition personnel to facilitate the application of the Conventions and this Protocol of the legal adviser’s role, while still of the Conventions and of Additional and on the appropriate instruction to laying down certain rules. -

Militärgerichtsbarkeit in Österreich (Circa 1850–1945)

BRGÖ 2016 Beiträge zur Rechtsgeschichte Österreichs Martin MOLL, Graz Militärgerichtsbarkeit in Österreich (circa 1850–1945) Military jurisdiction in Austria, ca. 1850–1945 This article starts around 1850, a period which saw a new codification of civil and military penal law with a more precise separation of these areas. Crimes committed by soldiers were now defined parallel to civilian ones. However, soldiers were still tried before military courts. The military penal code comprised genuine military crimes like deser- tion and mutiny. Up to 1912 the procedure law had been archaic as it did not distinguish between the state prosecu- tor and the judge. But in 1912 the legislature passed a modern military procedure law which came into practice only weeks before the outbreak of World War I, during which millions of trials took place, conducted against civilians as well as soldiers. This article outlines the structure of military courts in Austria-Hungary, ranging from courts responsible for a single garrison up to the Highest Military Court in Vienna. When Austria became a republic in November 1918, military jurisdiction was abolished. The authoritarian government of Chancellor Engelbert Dollfuß reintroduced martial law in late 1933; it was mainly used against Social Democrats who staged the February 1934 uprising. After the National Socialist ‘July putsch’ of 1934 a military court punished the rioters. Following Aus- tria’s annexation to Germany in 1938, German military law was introduced in Austria. After the war’s end in 1945, these Nazi remnants were abolished, leaving Austria without any military jurisdiction. Keywords: Austria – Austria as part of Hitler’s Germany –First Republic – Habsburg Monarchy – Military Jurisdiction Einleitung und Themenübersicht allen Staaten gab es eine eigene, von der zivilen Justiz getrennte Strafgerichtsbarkeit des Militärs. -

The Civilianization of Military Law

THE CIVILIANIZATION OF MILITARY LAW Edward F. Sherman* PART I I. INTRODUCTION Military law in the United States has always functioned as a system of jurisprudence independent of the civilian judiciary. It has its own body of substantive laws and procedures which has a different historical deri- vation than the civilian criminal law. The first American Articles of War, enacted by the Continental Congress in 1775,1 copied the British Arti- cles, a body of law which had evolved from the 17th century rules adopted by Gustavus Adolphus for the discipline of his army, rather than from the English common law.2 Despite subsequent alterations by Con- gress, the American military justice code still retains certain substantive and procedural aspects of the 18th century British code. Dissimilarity between military and civilian criminal law has been further encouraged by the isolation of the court-martial system. The federal courts have always been reluctant to interfere with the court-martial system, as ex- plained by the Supreme Court in 1953 in Burns v. Wilson:3 "Military law, like state law, is a jurisprudence which exists separate and apart from the law which governs in our federal judicial establishment. This Court has played no role in its development; we have exerted no super- visory power over the courts which enforce it .... As a result, the court-martial system still differs from the civilian court system in such aspects as terminology and structure, as well as procedural and sub- stantive law. The military has jealously guarded the distinctive aspects of its system of justice. -

The Rise and Fall of an Internationally Codified Denial of the Defense of Superior Orders

xv The Rise and Fall of an Internationally Codified Denial of the Defense of Superior Orders 30 Revue De Droit Militaire Et De Droit De LA Guerre 183 (1991) Introduction s long as there have been trials for violations of the laws and customs of A war, more popularly known as "war crimes trials", the trial tribunals have been confronted with the defense of "superior orders"-the claim that the accused did what he did because he was ordered to do so by a superior officer (or by his Government) and that his refusal to obey the order would have brought dire consequences upon him. And as along as there have been trials for violations of the laws and customs ofwar the trial tribunals have almost uniformly rejected that defense. However, since the termination of the major programs of war crimes trials conducted after World War II there has been an ongoing dispute as to whether a plea of superior orders should be allowed, or disallowed, and, if allowed, the criteria to be used as the basis for its application. Does international action in this area constitute an invasion of the national jurisdiction? Should the doctrine apply to all war crimes or only to certain specifically named crimes? Should the illegality of the order received be such that any "reasonable" person would recognize its invalidity; or should it be such as to be recognized by a person of"ordinary sense and understanding"; or by a person ofthe "commonest understanding"? Should it be "illegal on its face"; or "manifesdy illegal"; or "palpably illegal"; or of "obvious criminality,,?1 An inability to reach a generally acceptable consensus on these problems has resulted in the repeated rejection of attempts to legislate internationally in this area. -

The Imposition of Martial Law in the United States

THE IMPOSITION OF MARTIAL LAW IN THE UNITED STATES MAJOR KIRK L. DAVIES WTC QUALTPy m^CT^^ A 20000112 078 Form Approved REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reDOrtino burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, a^^r^6<^mim\ngxh^a^BäJ, and completing and reviewing the collection of information Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any^othe aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Inforrnatior.Ope.rations and Reporte, 1215 Jefferson Davfei wShwa? Suit? 1:204 Arlington: VA 22202-4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Pro]ect (0704-01881, Washington, DC 20503. 1. AGENCY USE ONLY (Leave blank) 2. REPORT DATE REPORT TYPE AND DATES COVERED 3Jan.OO MAJOR REPORT 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5. FUNDING NUMBERS THE IMPOSITION OF MARTIAL LAW IN UNITED STATES 6. AUTHOR(S) MAJ DAVIES KIRK L 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 8. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION REPORT NUMBER JA GENERAL SCHOOL ARMY 9. SPONSORING/MONITORING AGENCY NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 10. SPONSORING/MONITORING AGENCY REPORT NUMBER THE DEPARTMENT OF THE AIR FORCE AFIT/CIA, BLDG 125 FY99-603 2950 P STREET WPAFB OH 45433 11. SUPPLEMENTARY NOTES 12a. DISTRIBUTION AVAILABILITY STATEMENT 12b. DISTRIBUTION CODE Unlimited distribution In Accordance With AFI 35-205/AFIT Sup 1 13. ABSTRACT tMaximum 200 words) DISTRIBUTION STATEMENT A Approved for Public Release Distribution Unlimited 14. SUBJECT TERMS 15. NUMBER OF PAGES 61 16. -

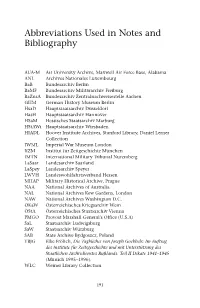

Abbreviations Used in Notes and Bibliography

Abbreviations Used in Notes and Bibliography AUA-M Air University Archive, Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama ANL Archives Nationales Luxembourg BaB Bundesarchiv Berlin BaMF Bundesarchiv Militärarchiv Freiburg BaZnsA Bundesarchiv Zentralnachweisestelle Aachen GHM German History Museum Berlin HsaD Hauptstaatsarchiv Düsseldorf HasH Hauptstaatsarchiv Hannover HSaM Hessisches Staatsarchiv Marburg HStAWi Hauptstaatsarchiv Wiesbaden HIADL Hoover Institute Archives, Stanford Library, Daniel Lerner Collection IWML Imperial War Museum London IfZM Institut für Zeitgeschichte München IMTN International Military Tribunal Nuremberg LaSaar Landesarchiv Saarland LaSpey Landesarchiv Speyer LWVH Landeswohlfahrtsverband Hessen MHAP Military Historical Archive, Prague NAA National Archives of Australia NAL National Archives Kew Gardens, London NAW National Archives Washington D.C. OKaW Österreichisches Kriegsarchiv Wein ÖStA Österreichisches Staatsarchiv Vienna PMGO Provost Marshall General’s Office (U.S.A) SaL Staatsarchiv Ludwigsburg SaW Staatsarchiv Würzburg SAB State Archive Bydgoszcz, Poland TBJG Elke Frölich, Die Tagbücher von Joseph Goebbels: Im Auftrag des Institute für Zeitsgeschichte und mit Unterstützung des Staatlichen Archivdienstes Rußlands. Teil II Dikate 1941–1945 (Münich 1995–1996). WLC Weiner Library Collection 191 Notes Introduction: Sippenhaft, Terror and Fear: The Historiography of the Nazi Terror State 1 . Christopher Hutton, Race and the Third Reich: Linguistics, Racial Anthropology and Genetics in the Third Reich (Cambridge 2005), p. 18. 2 . Rosemary O’Kane, Terror, Force and States: The Path from Modernity (Cheltham 1996), p. 19. O’Kane defines a system of terror, as one that is ‘distinguished by summary justice, where the innocence or guilt of the victims is immaterial’. 3 . See Robert Thurston, ‘The Family during the Great Terror 1935–1941’, Soviet Studies , 43, 3 (1991), pp. 553–74. -

Continuing Civilianization of the Military Criminal Legal System Fredric I

College of William & Mary Law School William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository Faculty Publications Faculty and Deans 2017 From Rome to the Military Justice Acts of 2016 and beyond: Continuing Civilianization of the Military Criminal Legal System Fredric I. Lederer William & Mary Law School, [email protected] Repository Citation Lederer, Fredric I., "From Rome to the Military Justice Acts of 2016 and beyond: Continuing Civilianization of the Military Criminal Legal System" (2017). Faculty Publications. 1943. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/facpubs/1943 Copyright c 2017 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/facpubs 512 MILITARY LAw REVIEW [Vol. 225 FROM ROME TO THE MILITARY JUSTICE ACTS OF 2016 AND BEYOND: CONTINUING CIVILIANIZATION OF THE MILITARY CRIMINAL LEGAL SYSTEM FREDRIC I. LEDERER* I. Introduction The recent, but unenacted, proposed Military Justice Act of 2016,' the very different and less ambitious, but enacted, Military Justice Act of 2016,2 and congressional actions and proposals to sharply modify the military criminal legal system to combat sexual assault and harassment3 provide both opportunity and necessity to reevaluate the fundamental need for and nature of the military criminal legal system. With the exception of the 1962 amendment to Article 15 of the Uniform Code of Military Justice to enhance the commander's punishment authority,' the modem history of military criminal law largely is defined by its increasing civilianization. My thesis is that we are close to the point at which that process will no longer meet the disciplinary needs of the modem armed forces, if, indeed, it does today. -

The Domestic Implementation of International Humanitarian Law a Manual

THE DOMESTIC IMPLEMENTATION OF INTERNATIONAL HUMANITARIAN LAW A MANUAL ICRC national implementation database http://www.icrc.org/ihl-nat Treaty database and States Party http://www.icrc.org/ihl THE DOMESTIC IMPLEMENTATION OF INTERNATIONAL HUMANITARIAN LAW A MANUAL Geneva, Mont Blanc bridge. Flags on the occasion of the 30th International Conference of the Red Cross and Red Crescent. © Jorge Perez/Federation CONTENTS Contents FOREWORD .............................................................................................................. 5 AIM OF THIS MANUAL .................................................................................................... 7 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................................................... 9 1 CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION – THE BASICS OF IHL 11 2 CHAPTER TWO: IHL TREATIES AND NATIONAL IMPLEMENTATION 17 3 CHAPTER THREE: IHL AND DOMESTIC CRIMINAL LAW 27 4 CHAPTER FOUR: THE GENEVA CONVENTIONS AND THEIR ADDITIONAL PROTOCOLS 43 5 CHAPTER FIVE: TREATIES CONCERNING PEOPLE AND PROPERTY IN ARMED CONFLICT 63 6 CHAPTER SIX: WEAPONS TREATIES 79 7 CHAPTER SEVEN: THE INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL COURT 119 8 CHAPTER EIGHT: SUPPORT FOR IHL IMPLEMENTATION 129 ANNEXES RELEVANT SITES BIBLIOGRAPHY 3 FOREWORD Foreword The people most severely affected by armed conflict are This Manual on the Implementation of International increasingly those who are not or who are no longer taking Humanitarian Law, prepared by the ICRC’s Advisory Service, part in the fighting. International humanitarian -

THE SCOPE of MILITARY JUSTICE Delmar Karlen and Louis H

Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Volume 43 | Issue 3 Article 1 1952 The copS e of Military Justice Delmar Karlen Louis H. Pepper Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminology Commons, and the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation Delmar Karlen, Louis H. Pepper, The cS ope of Military Justice, 43 J. Crim. L. Criminology & Police Sci. 285 (1952-1953) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by an authorized editor of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. JOURNAL OF CRIMINAL LAW, CRIMINOLOGY, AND POLICE SCIENCE September-October, 1952 Vol. 43, No. 3 THE SCOPE OF MILITARY JUSTICE Delmar Karlen and Louis H. Pepper Delmar Karlen is Professor of Law in the University of Wisconsin School of Law and Lt. Col., J.A.G.C., U.S. Army Reserve. He is a member of the bars of New York and Wisconsin. He is now on leave, serving as visiting Professor of Law at New York University. Louis H. Pepper received the LL.B. in the University of Wisconsin in 1951. He is a member of the Wisconsin Bar.-EDITOR. Symptomatic of prevailing attitudes toward military justice is the recent remark of a law school professor upon hearing a proposal to offer a course in the subject at his school: "Humph I We might as well teach canon law." No pun was intended. -

Military Ranks

WHO WILL SERVE? EDUCATION, LABOR MARKETS, AND MILITARY PERSONNEL POLICY by Lindsay P. Cohn Department of Political Science Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Peter D. Feaver, Supervisor ___________________________ David Soskice ___________________________ Christopher Gelpi ___________________________ Tim Büthe ___________________________ Alexander B. Downes Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Political Science in the Graduate School of Duke University 2007 ABSTRACT WHO WILL SERVE? EDUCATION, LABOR MARKETS, AND MILITARY PERSONNEL POLICY by Lindsay P. Cohn Department of Political Science Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Peter D. Feaver, Supervisor ___________________________ David Soskice ___________________________ Christopher Gelpi ___________________________ Tim Büthe ___________________________ Alexander B. Downes An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Political Science in the Graduate School of Duke University 2007 Copyright by Lindsay P. Cohn 2007 Abstract Contemporary militaries depend on volunteer soldiers capable of dealing with advanced technology and complex missions. An important factor in the successful recruiting, retention, and employment of quality personnel is the set of personnel policies which a military has in place. It might be assumed that military policies on personnel derive solely from the functional necessities of the organization’s mission, given that the stakes of military effectiveness are generally very high. Unless the survival of the state is in jeopardy, however, it will seek to limit defense costs, which may entail cutting into effectiveness. How a state chooses to make the tradeoffs between effectiveness and economy will be subject to influences other than military necessity. -

War Crimes Act of 1996

104TH CONGRESS REPORT 2d Session HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES 104±698 "! WAR CRIMES ACT OF 1996 JULY 24, 1996.ÐCommitted to the Committee of the Whole House on the State of the Union and ordered to be printed Mr. SMITH of Texas, from the Committee on the Judiciary, submitted the following REPORT [To accompany H.R. 3680] [Including cost estimate of the Congressional Budget Office] The Committee on the Judiciary, to whom was referred the bill (H.R. 3680) to amend title 18, United States Code, to carry out the international obligations of the United States under the Geneva Conventions to provide criminal penalties for certain war crimes, having considered the same, report favorably thereon without amendment and recommend that the bill do pass. CONTENTS Page Purpose and Summary ............................................................................................ 1 Background and Need for Legislation .................................................................... 2 Hearings ................................................................................................................... 9 Committee Consideration ........................................................................................ 9 Vote of the Committee ............................................................................................. 10 Committee Oversight Findings ............................................................................... 10 Committee on Government Reform and Oversight Findings ............................... 10 New Budget Authority -

Targeting, the Law of War, and the Uniform Code of Military Justice

Targeting, the Law of War, and the Uniform Code of Military Justice Michael W. Meier & James T. Hill* ABSTRACT Allegations of civilian deaths or injury or damage to civilian property caused during combat operations require an investigation to determine the facts, make recommendations regarding lessons learned in order to prevent future occurrences, and recommend whether individual soldiers should be held accountable. Using the factual circumstances of the airstrike on the Médecins Sans Frontières hospital, this Article articulates how, in the context of targeting, a violation of the Law of War is made punishable under the Uniform Code of Military Justice as explained by the recent Targeting Supplement promulgated by The Judge Advocate General of the Army. TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION .............................................................. 788 II. AIRSTRIKE ON THE MSF HOSPITAL ............................... 791 III. ERRORS IN JUDGMENT AND THE LAW OF WAR .............. 794 IV. TARGETING, THE LAW OF WAR, AND MENS REA ............ 796 A. Targeting Duties .......................................... 796 B. Information Assessment Duties ................... 798 C. Mens Rea ...................................................... 799 D. Competent Authority Required .................... 799 V. THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN DOMESTIC LAW AND THE LAW OF WAR .......................................................... 800 VI. THE LAW OF WAR AND THE UCMJ ............................... 802 * Michael W. Meier is the Special Assistant to the Judge Advocate General for Law of War Matters with the Department of the Army. The author wants to thank the Israeli Defense Forces for the opportunity to speak at its 2nd IDF Annual Conference on LOAC panel on ground operations, which is the basis for this article. James T. Hill is currently the Deputy Staff Judge Advocate at 8th Army in Korea. He previously served at the International and Operational Law Division, Office of the Judge Advocate General.