Characteristics of Style in the Song Cycle Don Quichotte À Dulcinée

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Don Quichotte Don Quixote Page 1 of 4 Opera Assn

San Francisco War Memorial 1990 Don Quichotte Don Quixote Page 1 of 4 Opera Assn. Opera House This presentation of "Don Quichotte" is made possible, in part, by a generous gift from Mr. & Mrs. Thomas Tilton Don Quichotte (in French) Opera in five acts by Jules Massenet Libretto by Henri Cain Based on play by Jacques Le Lorrain, based on Cervantes Conductor CAST Julius Rudel Pedro Mary Mills Production Garcias Kathryn Cowdrick Charles Roubaud † Rodriguez Kip Wilborn Lighting Designer Juan Dennis Petersen Joan Arhelger Dulcinée's Friend Michael Lipsky Choreographer Dulcinée Katherine Ciesinski Victoria Morgan Don Quichotte Samuel Ramey Chorus Director Sancho Pança Michel Trempont Ian Robertson The Bandit Chief Dale Travis Musical Preparation First Bandit Gerald Johnson Ernest Fredric Knell Second Bandit Daniel Pociernicki Susanna Lemberskaya First Servant Richard Brown Susan Miller Hult Second Servant Cameron Henley Christopher Larkin Svetlana Gorzhevskaya *Role debut †U.S. opera debut Philip Eisenberg Kathryn Cathcart PLACE AND TIME: Seventeenth-century Spain Prompter Philip Eisenberg Assistant Stage Director Sandra Bernhard Assistant to Mr. Roubaud Bernard Monforte † Supertitles Christopher Bergen Stage Manager Jamie Call Thursday, October 11 1990, at 8:00 PM Act I -- The poor quarter of a Spanish town Sunday, October 14 1990, at 2:00 PM INTERMISSION Thursday, October 18 1990, at 7:30 PM Act II -- In the countryside at dawn Saturday, October 20 1990, at 8:00 PM Act III -- The bandits' camp Tuesday, October 23 1990, at 8:00 PM INTERMISSION Friday, October 26 1990, at 8:00 PM Act IV -- The poor quarter Act V -- In the countryside at night San Francisco War Memorial 1990 Don Quichotte Don Quixote Page 2 of 4 Opera Assn. -

(MTO 21.1: Stankis, Ravel's ficolor

Volume 21, Number 1, March 2015 Copyright © 2015 Society for Music Theory Maurice Ravel’s “Color Counterpoint” through the Perspective of Japonisme * Jessica E. Stankis NOTE: The examples for the (text-only) PDF version of this item are available online at: http://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.15.21.1/mto.15.21.1.stankis.php KEYWORDS: Ravel, texture, color, counterpoint, Japonisme, style japonais, ornament, miniaturism, primary nature, secondary nature ABSTRACT: This article establishes a link between Ravel’s musical textures and the phenomenon of Japonisme. Since the pairing of Ravel and Japonisme is far from obvious, I develop a series of analytical tools that conceptualize an aesthetic orientation called “color counterpoint,” inspired by Ravel’s fascination with Chinese and Japanese art and calligraphy. These tools are then applied to selected textures in Ravel’s “Habanera,” and “Le grillon” (from Histoires naturelles ), and are related to the opening measures of Jeux d’eau and the Sonata for Violin and Cello . Visual and literary Japonisme in France serve as a graphical and historical foundation to illuminate how Ravel’s color counterpoint may have been shaped by East Asian visual imagery. Received August 2014 1. Introduction It’s been given to [Ravel] to bring color back into French music. At first he was taken for an impressionist. For a while he encountered opposition. Not a lot, and not for long. And once he got started, what production! —Léon-Paul Fargue, 1920s (quoted in Beucler 1954 , 53) Don’t you think that it slightly resembles the gardens of Versailles, as well as a Japanese garden? —Ravel describing his Le Belvédère, 1931 (quoted in Orenstein 1990 , 475) In “Japanizing” his garden, Ravel made unusual choices, like his harmonies. -

MASSENET and HIS OPERAS Producing at the Average Rate of One Every Two Years

M A S S E N E T AN D HIS O PE RAS l /O BY HENRY FIN T. CK AU THO R O F ” ” Gr ie and His Al y sia W a ner and H W g , g is or ks , ” S uccess in Music and it W How is on , E ta , E tc. NEW YO RK : JO HN LANE CO MPANY MCMX LO NDO N : O HN L NE THE BO DLEY HE D J A , A K N .Y . O MP NY N E W Y O R , , P U B L I S HE R S P R I NTI N G C A , AR LEE IB R H O LD 8 . L RA Y BRIGHAM YO UNG UNlVERS lTW AH PRO VO . UT TO MY W I FE CO NTENTS I MASSENET IN AMER . ICA. H . B O GRAP KET H II I IC S C . P arents and Chi dhoo . At the Conservatoire l d . Ha D a n R m M rri ppy ys 1 o e . a age and Return to r H P a is . C oncert a Successes . In ar Time ll W . A n D - Se sational Sacred rama. M ore Semi religious m W or s . P ro e or and Me r of n i u k f ss be I st t te . P E R NAL R D III SO T AITS AN O P INIO NS . A P en P ic ure er en ne t by Servi es . S sitive ss to Griti m h cis . -

The Choral Cycle

THE CHORAL CYCLE: A CONDUCTOR‟S GUIDE TO FOUR REPRESENTATIVE WORKS A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE DOCTOR OF ARTS BY RUSSELL THORNGATE DISSERTATION ADVISORS: DR. LINDA POHLY AND DR. ANDREW CROW BALL STATE UNIVERSITY MUNCIE, INDIANA MAY 2011 Contents Permissions ……………………………………………………………………… v Introduction What Is a Choral Cycle? .............................................................................1 Statement of Purpose and Need for the Study ............................................4 Definition of Terms and Methodology .......................................................6 Chapter 1: Choral Cycles in Historical Context The Emergence of the Choral Cycle .......................................................... 8 Early Predecessors of the Choral Cycle ....................................................11 Romantic-Era Song Cycles ..................................................................... 15 Choral-like Genres: Vocal Chamber Music ..............................................17 Sacred Cyclical Choral Works of the Romantic Era ................................20 Secular Cyclical Choral Works of the Romantic Era .............................. 22 The Choral Cycle in the Twentieth Century ............................................ 25 Early Twentieth-Century American Cycles ............................................. 25 Twentieth-Century European Cycles ....................................................... 27 Later Twentieth-Century American -

RECORDED RICHTER Compiled by Ateş TANIN

RECORDED RICHTER Compiled by Ateş TANIN Previous Update: February 7, 2017 This Update: February 12, 2017 New entries (or acquisitions) for this update are marked with [N] and corrections with [C]. The following is a list of recorded recitals and concerts by the late maestro that are in my collection and all others I am aware of. It is mostly indebted to Alex Malow who has been very helpful in sharing with me his extensive knowledge of recorded material and his website for video items at http://www.therichteracolyte.org/ contain more detailed information than this list.. I also hope for this list to get more accurate and complete as I hear from other collectors of one of the greatest pianists of our era. Since a discography by Paul Geffen http://www.trovar.com/str/ is already available on the net for multiple commercial issues of the same performances, I have only listed for all such cases one format of issue of the best versions of what I happened to have or would be happy to have. Thus the main aim of the list is towards items that have not been generally available along with their dates and locations. Details of Richter CDs and DVDs issued by DOREMI are at http://www.doremi.com/richter.html . Please contact me by e-mail:[email protected] LOGO: (CD) = Compact Disc; (SACD) = Super Audio Compact Disc; (BD) = Blu-Ray Disc; (LD) = NTSC Laserdisc; (LP) = LP record; (78) = 78 rpm record; (VHS) = Video Cassette; ** = I have the original issue ; * = I have a CD-R or DVD-R of the original issue. -

The Genre of the Minuet in the Works of Maurice Ravel

Journal of Siberian Federal University. Humanities & Social Sciences 1 (2016 9) 41-54 ~ ~ ~ УДК 78.085 The Genre of the Minuet in the Works of Maurice Ravel Valentina V. Bass* Krasnoyarsk State Institute of Art 22 Lenin Str., Krasnoyarsk, 660049, Russia Received 19.07.2015, received in revised form 21.08.2015, accepted 30.08.2015 The article deals with the key issue of modern musicology, the issue of a certain genre that prevails in the works of a music composer, an ability of a genre to become a factor that determines stylistic specificity. In the works of Maurice Ravel this style-forming factor is dance. On the example of the minuet that occupies a special place in the works of the composer, the article explores the principles of mediation of choreographic and musical features of the dance prototype at the semantic and structural levels in the thematism and form generation of Ravel’s works. The aesthetic perfection and delicate elegance of gestures, graphical precision of choreographic pattern and dialogueness typical for the minuet have been reflected in the motive-composition character of the thematism, the periodicity of the syntax, the relative stability of the meter, the active use of various methods of polyphonization of the musical texture, the exclusive role of the principle of symmetry on the compositional, melodic and textural levels of the musical form. Individual features of the minuet in various works of Ravel are related to their stylistic origins and genre fusion creating certain imagery. Keywords: minuet, dance prototype, choreographic pattern of dance, genre semantics, counter rhythm, figurative polyphony, stylistic multilayers. -

"Gioconda" Rings Up-The Curtain At

Vol. XIX. No. 3 NEW YORK EDITED ~ ~ ....N.O.V.E.M_B_E_R_2_2 ,_19_1_3__ T.en.~! .~Ot.~:_:r.rl_::.: ... "GIOCONDA" RINGS "DON QUICHOTTE"HAS UP- THE CURTAIN AMERICANPREMIERE AT METROPOLITAN Well Performed by Chicago Com pany in Philadelphia- Music A Spirited Performance with Ca in Massenet's Familiar Vein ruso in Good 'Form at Head B ureau of Musical A m erica, of the Cas t~Amato, Destinn Sixt ee nth and Chestn ut Sts., Philadel phia, Novem ber 17. 1913.. and Toscanini at Their Best T HE first real novelty of the local opera Audience Plays Its Own Brilliant season was offered at the Metropolitan Part Brilliantly-Geraldine Far last Saturday afternoon, when Mas senet's "Don Quichotte" had its American rar's Cold Gives Ponchielli a premiere, under the direction of Cleofonte Distinction That Belonged to Campanini, with Vanni Marcoux in the Massenet title role, which he had sung many times in Europe; Hector Dufranne as Sancho W ITH a spirited performance of "Gio- Panza, and Mary Garden as La Belle Dul conda" the Metropolitan Opera cinea. The performance was a genuine Company began its season last M'o;day success. The score is in Massenet's fa night. The occasion was as brilliant as miliar vein: It offers a continuous flow of others that have gone before, and if it is melody, light, sometimes almost inconse quential, and not often of dramatic signifi not difficult to recall premieres of greater cance, but at all times pleasing, of an ele artistic pith and moment it behooves the gance that appeals to the aesthetic sense, chronicler of the august event to record and in all its phases appropriate to the the generally diffused glamor as a matter story, sketched rather briefly by Henri Cain from the voluminous romance of Miguel de of necessary convention, As us~al there Cervantes. -

May, 1952 TABLE of CONTENTS

111 AJ( 1 ~ toa TlE PIANO STYI2 OF AAURICE RAVEL THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State College in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS by Jack Lundy Roberts, B. I, Fort Worth, Texas May, 1952 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OFLLUSTRTIONS. Chapter I. THE DEVELOPMENT OF PIANO STYLE ... II. RAVEL'S MUSICAL STYLE .. # . , 7 Melody Harmony Rhythm III INFLUENCES ON RAVEL'S EIANO WORKS . 67 APPENDIX . .* . *. * .83 BTBLIO'RAWp . * *.. * . *85 iii LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Figure Page 1. Jeux d'Eau, mm. 1-3 . .0 15 2. Le Paon (Histoires Naturelles), mm. la-3 .r . -* - -* . 16 3. Le Paon (Histoires Naturelles), 3 a. « . a. 17 4. Ondine (Gaspard de a Nuit), m. 1 . .... 18 5. Ondine (Gaspard de la Nuit), m. 90 . 19 6. Sonatine, first movement, nm. 1-3 . 21 7. Sonatine, second movement, 22: 8. Sonatine, third movement, m m . 3 7 -3 8 . ,- . 23 9. Sainte, umi. 23-25 . * * . .. 25 10. Concerto in G, second movement, 25 11. _Asi~e (Shehdrazade ), mm. 6-7 ... 26 12. Menuet (Le Tombeau de Coupe rin), 27 13. Asie (Sh6hlrazade), mm. 18-22 . .. 28 14. Alborada del Gracioso (Miroirs), mm. 43%. * . 8 28 15. Concerto for the Left Hand, mii 2T-b3 . *. 7-. * * * .* . ., . 29 16. Nahandove (Chansons Madecasses), 1.Snat ,-5 . * . .o .t * * * . 30 17. Sonat ine, first movement, mm. 1-3 . 31 iv Figure Page 18. Laideronnette, Imperatrice des l~~e),i.......... Pagodtes (jMa TV . 31 19. Saint, mm. 4-6 « . , . ,. 32 20. Ondine (caspard de la Nuit), in. 67 .. .4 33 21. -

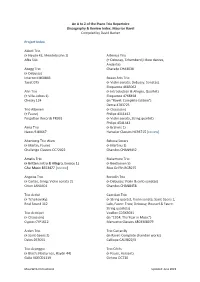

Ravel Compiled by David Barker

An A to Z of the Piano Trio Repertoire Discography & Review Index: Maurice Ravel Compiled by David Barker Project Index Abbot Trio (+ Haydn 43, Mendelssohn 1) Artenius Trio Afka 544 (+ Debussy, Tchemberdji: Bow dances, Andante) Abegg Trio Charade CHA3038 (+ Debussy) Intercord 860866 Beaux Arts Trio Tacet 075 (+ Violin sonata; Debussy: Sonatas) Eloquence 4683062 Ahn Trio (+ Introduction & Allegro, Quartet) (+ Villa-Lobos 1) Eloquence 4768458 Chesky 124 (in “Ravel: Complete Edition”) Decca 4783725 Trio Albeneri (+ Chausson) (+ Faure) Philips 4111412 Forgotten Records FR991 (+ Violin sonata, String quartet) Philips 4541342 Alma Trio (+ Brahms 1) Naxos 9.80667 Hanssler Classics HC93715 [review] Altenberg Trio Wien Bekova Sisters (+ Martin, Faure) (+ Martinu 1) Challenge Classics CC72022 Chandos CHAN9452 Amatis Trio Blakemore Trio (+ Britten: Intro & Allegro, Enescu 1) (+ Beethoven 5) CAvi Music 8553477 [review] Blue Griffin BGR275 Angelus Trio Borodin Trio (+ Cortes, Grieg: Violin sonata 2) (+ Debussy: Violin & cello sonatas) Orion LAN0401 Chandos CHAN8458 Trio Arché Caecilian Trio (+ Tchaikovsky) (+ String quartet, Violin sonata; Saint-Saens 1, Real Sound 112 Lalo, Faure: Trios; Debussy, Roussel & Faure: String quartets) Trio Archipel VoxBox CD3X3031 (+ Chausson) (in “1914: The Year in Music”) Cypres CYP1612 Menuetto Classics 4803308079 Arden Trio Trio Carracilly (+ Saint-Saens 2) (in Ravel: Complete chamber works) Delos DE3055 Calliope CAL3822/3 Trio Arpeggio Trio Cérès (+ Bloch: Nocturnes, Haydn 44) (+ Faure, Hersant) Gallo VDECD1119 Oehms -

Menuet from Sonatine Maurice Ravel Transcribed for Violin and Piano Sheet Music

Menuet From Sonatine Maurice Ravel Transcribed For Violin And Piano Sheet Music Download menuet from sonatine maurice ravel transcribed for violin and piano sheet music pdf now available in our library. We give you 4 pages partial preview of menuet from sonatine maurice ravel transcribed for violin and piano sheet music that you can try for free. This music notes has been read 4071 times and last read at 2021-09-27 14:22:05. In order to continue read the entire sheet music of menuet from sonatine maurice ravel transcribed for violin and piano you need to signup, download music sheet notes in pdf format also available for offline reading. Instrument: Violin Solo, Piano Accompaniment Ensemble: Mixed Level: Advanced [ READ SHEET MUSIC ] Other Sheet Music Menuet From Sonatine 1905 By Maurice Ravel Transcribed For Flute And Piano Menuet From Sonatine 1905 By Maurice Ravel Transcribed For Flute And Piano sheet music has been read 3015 times. Menuet from sonatine 1905 by maurice ravel transcribed for flute and piano arrangement is for Advanced level. The music notes has 4 preview and last read at 2021-09-27 03:53:13. [ Read More ] Mouvement De Menuet From Sonatine By Maurice Ravel Mouvement De Menuet From Sonatine By Maurice Ravel sheet music has been read 6722 times. Mouvement de menuet from sonatine by maurice ravel arrangement is for Advanced level. The music notes has 1 preview and last read at 2021-09-28 10:04:05. [ Read More ] Maurice Ravel Menuet Sur Le Nom De Haydn Complete Version Maurice Ravel Menuet Sur Le Nom De Haydn Complete Version sheet music has been read 3455 times. -

Cervantes the Cervantes Society of America Volume Xxvi Spring, 2006

Bulletin ofCervantes the Cervantes Society of America volume xxvi Spring, 2006 “El traducir de una lengua en otra… es como quien mira los tapices flamencos por el revés.” Don Quijote II, 62 Translation Number Bulletin of the CervantesCervantes Society of America The Cervantes Society of America President Frederick De Armas (2007-2010) Vice-President Howard Mancing (2007-2010) Secretary-Treasurer Theresa Sears (2007-2010) Executive Council Bruce Burningham (2007-2008) Charles Ganelin (Midwest) Steve Hutchinson (2007-2008) William Childers (Northeast) Rogelio Miñana (2007-2008) Adrienne Martin (Pacific Coast) Carolyn Nadeau (2007-2008) Ignacio López Alemany (Southeast) Barbara Simerka (2007-2008) Christopher Wiemer (Southwest) Cervantes: Bulletin of the Cervantes Society of America Editors: Daniel Eisenberg Tom Lathrop Managing Editor: Fred Jehle (2007-2010) Book Review Editor: William H. Clamurro (2007-2010) Editorial Board John J. Allen † Carroll B. Johnson Antonio Bernat Francisco Márquez Villanueva Patrizia Campana Francisco Rico Jean Canavaggio George Shipley Jaime Fernández Eduardo Urbina Edward H. Friedman Alison P. Weber Aurelio González Diana de Armas Wilson Cervantes, official organ of the Cervantes Society of America, publishes scholarly articles in Eng- lish and Spanish on Cervantes’ life and works, reviews, and notes of interest to Cervantistas. Tw i ce yearly. Subscription to Cervantes is a part of membership in the Cervantes Society of America, which also publishes a newsletter: $20.00 a year for individuals, $40.00 for institutions, $30.00 for couples, and $10.00 for students. Membership is open to all persons interested in Cervantes. For membership and subscription, send check in us dollars to Theresa Sears, 6410 Muirfield Dr., Greensboro, NC 27410. -

Don Quichotte Fiche Pédagogique

12 > 17 MARS 2019 DON QUICHOTTE OPÉRA PARTICIPATIF Inspiré librement de Don Quichotte de Jules Massenet FICHE PÉDAGOGIQUE SAISON 2018 .19 WWW.OPERALIEGE.BE LE ROMAN DE CERVANTES 400 ANS DE SUCCÈS Don Quichotte est un personnage imaginaire tout droit sorti d’un livre, en deux parties, écrit il y a plus de 400 ans par l’écrivain espagnol Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra (1547-1616). Le titre original, El Ingenioso Hidalgo Don Quijote de la ? Mancha , peut être traduit par «L’ingénieux noble Don Quichotte de la Manche». Considéré comme le premier roman moderne, c’est encore de nos jours un des livres les plus lus au monde! ? L’histoire de Cervantes conte les aventures d’un pauvre hidalgo, dénommé Alonso Quichano, et tellement obsédé par les romans de chevalerie qu’il finit un jour par se prendre pour le chevalier errant Don Quichotte, dont la mission est de parcourir l’Espagne pour combattre le mal et protéger les opprimés. Même s’il est rangé de nos jours parmi les chefs-d’oeuvre classiques, cet ouvrage ? était considéré à l’époque de Cervantes comme un roman comique, une parodie des romans de chevalerie, très à la mode au Moyen Âge en Europe. Il fait également partie d'une tradition littéraire typiquement espagnole, celle du roman picaresque (de l'espagnol pícaro, « misérable », « futé »), genre littéraire dans lequel un héros, pauvre, raconte ses aventures. Gravure de FREDERICK MACKENZIE (1788-1854) représentant CERVANTES Le roman de Cervantes et le personnage de Don Quichotte ont inspiré de nombreux artistes peintres ou sculpteurs et ont donné naissance à de multiples adaptations en films, livres, chansons, opéras, comédies musicales, ballets ou encore pièces de théâtre.