Download Annual Public Health Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transport for the South East – Consent for Submission of Proposal to Government

CABINET 7 APRIL 2020 TRANSPORT FOR THE SOUTH EAST – CONSENT FOR SUBMISSION OF PROPOSAL TO GOVERNMENT Portfolio Holder: Councillor Phil Filmer, Portfolio Holder for Front Line Services Report from: Richard Hicks, Director of Place and Deputy Chief Executive Author: Michael Edwards, Head of Integrated Transport Summary This report seeks Cabinet support for the creation of a Sub-National Transport Body for the South East, confirmation of Medway’s position as a constituent authority, and consent for the submission of a Proposal to Government for statutory status. 1. Budget and Policy Framework 1.1 Medway Council does not have a stated policy position on Sub-National Transport Bodies. It is possible, however, to align the principles behind its creation with the Council’s priority of maximising regeneration and economic growth. 2. Background 2.1 Transport for the South East (TfSE) formed as a shadow Sub-National Transport Body (STB) in June 2017, and brings together sixteen local transport authorities: Bracknell Forest, Brighton and Hove, East Sussex, Hampshire, Isle of Wight, Medway, Kent, Portsmouth, Reading, Slough, Southampton, Surrey, West Berkshire, West Sussex, Windsor and Maidenhead and Wokingham. The Shadow Partnership Board also includes arrangements for involving five Local Enterprise Partnerships in its governance process, along with two National Park Authorities, forty-four Boroughs and Districts in East Sussex, Hampshire, Kent, Surrey and West Sussex, and representatives from the transport industry. 2.2 TfSE’s aim, as set out in its vision statement, is to grow the South East’s economy by delivering a safe, sustainable, and integrated transport system that makes the South East area more productive and competitive, improves the quality of life for all residents, and protects and enhances its natural and built environment. -

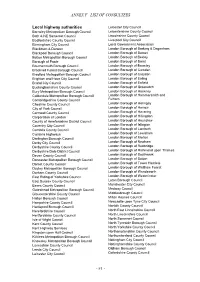

Annex F –List of Consultees

ANNEX F –LIST OF CONSULTEES Local highway authorities Leicester City Council Barnsley Metropolitan Borough Council Leicestershire County Council Bath & NE Somerset Council Lincolnshire County Council Bedfordshire County Council Liverpool City Council Birmingham City Council Local Government Association Blackburn & Darwen London Borough of Barking & Dagenham Blackpool Borough Council London Borough of Barnet Bolton Metropolitan Borough Council London Borough of Bexley Borough of Poole London Borough of Brent Bournemouth Borough Council London Borough of Bromley Bracknell Forest Borough Council London Borough of Camden Bradford Metropolitan Borough Council London Borough of Croydon Brighton and Hove City Council London Borough of Ealing Bristol City Council London Borough of Enfield Buckinghamshire County Council London Borough of Greenwich Bury Metropolitan Borough Council London Borough of Hackney Calderdale Metropolitan Borough Council London Borough of Hammersmith and Cambridgeshire County Council Fulham Cheshire County Council London Borough of Haringey City of York Council London Borough of Harrow Cornwall County Council London Borough of Havering Corporation of London London Borough of Hillingdon County of Herefordshire District Council London Borough of Hounslow Coventry City Council London Borough of Islington Cumbria County Council London Borough of Lambeth Cumbria Highways London Borough of Lewisham Darlington Borough Council London Borough of Merton Derby City Council London Borough of Newham Derbyshire County Council London -

Download Medway Council Sports Facility Strategy and Action Plan

MEDWAY COUNCIL Sports Facility Strategy and Action Plan November 2017 DOCUMENT CONTROL Amendment History Version No Date Author Comments 5 24/11/17 Taryn Dale Final Report Sign-off List Name Date Comments Tom Pinnington 24/11/17 Approved for distribution to client Distribution List Name Organisation Date Bob Dimond Medway Council 24/11/17 Medway Council 2 Sports Facility Strategy and Action Plan CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................... 5 1.1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 5 1.2 Project Brief ............................................................................................................................... 5 1.3 Methodology and Approach ...................................................................................................... 6 2 BACKGROUND AND POLICY REVIEW ...................................................................................... 7 2.1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 7 2.2 National Context ........................................................................................................................ 7 2.3 Local Policy Context ................................................................................................................ 12 2.4 Demographic Profile ............................................................................................................... -

Medway Council HEALTH and ADULT SOCIAL CARE OVERVIEW and SCRUTINY COMMITTEE

Medway Council HEALTH AND ADULT SOCIAL CARE OVERVIEW AND SCRUTINY COMMITTEE 18 February 2010 5:00 pm to 7:15 pm RECORD OF THE MEETING PRESENT: Councillors Avey Committee members: Councillors Avey, Bhutia, Gilry, Val Goulden, Gulvin, Hewett, Kemp, Maisey, Murray and O'Brien (Chairman) Co-opted members: Shirley Griffiths, LINk Co-ordinator Substitute members: Councillor Kenneth Bamber (for Councillor Griffin) Councillor Smith (for Councillor Sheila Kearney) Councillor Harriott (for Councillor Shaw) In attendance: Elizabeth Benjamin, Lawyer Rose Collinson, Director of Children and Adults Marion Dinwoodie, Chief Executive, NHS Medway Rosie Gunstone, Overview and Scrutiny Co-ordinator Lois Howell, Company Secretary, Medway NHS Foundation Trust Preeya Madhoo, Performance Manager, Adults Councillor Mason, Portfolio Holder for Adult Social Care David Quirke-Thornton, Assistant Director, Adult Social Care 616 RECORDS OF MEETINGS The records of the meetings held on 5 November 2009 and 21 January 2010 were agreed as correct records. This record is available on our website - www.medway.gov.uk 617 APOLOGIES FOR ABSENCE Apologies for absence were received from Councillors Griffin, Sheila Griffin and Shaw. 618 DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST The Chairman, Councillor O’Brien, declared a personal interest in any reference to the NHS by virtue of the fact that members of his family work within the NHS. Councillor Gilry declared a personal interest in any reference to Medway Maritime Hospital by virtue of the fact that she occasionally works there. Shirley Griffiths, LINk Co-ordinator, declared a personal interest in all items by virtue of being a member of Medway NHS Foundation Trust, a member of South East Coast Ambulance Trust and Medway Older People’s Board. -

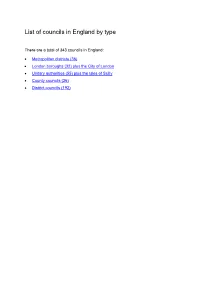

List of Councils in England by Type

List of councils in England by type There are a total of 343 councils in England: • Metropolitan districts (36) • London boroughs (32) plus the City of London • Unitary authorities (55) plus the Isles of Scilly • County councils (26) • District councils (192) Metropolitan districts (36) 1. Barnsley Borough Council 19. Rochdale Borough Council 2. Birmingham City Council 20. Rotherham Borough Council 3. Bolton Borough Council 21. South Tyneside Borough Council 4. Bradford City Council 22. Salford City Council 5. Bury Borough Council 23. Sandwell Borough Council 6. Calderdale Borough Council 24. Sefton Borough Council 7. Coventry City Council 25. Sheffield City Council 8. Doncaster Borough Council 26. Solihull Borough Council 9. Dudley Borough Council 27. St Helens Borough Council 10. Gateshead Borough Council 28. Stockport Borough Council 11. Kirklees Borough Council 29. Sunderland City Council 12. Knowsley Borough Council 30. Tameside Borough Council 13. Leeds City Council 31. Trafford Borough Council 14. Liverpool City Council 32. Wakefield City Council 15. Manchester City Council 33. Walsall Borough Council 16. North Tyneside Borough Council 34. Wigan Borough Council 17. Newcastle Upon Tyne City Council 35. Wirral Borough Council 18. Oldham Borough Council 36. Wolverhampton City Council London boroughs (32) 1. Barking and Dagenham 17. Hounslow 2. Barnet 18. Islington 3. Bexley 19. Kensington and Chelsea 4. Brent 20. Kingston upon Thames 5. Bromley 21. Lambeth 6. Camden 22. Lewisham 7. Croyd on 23. Merton 8. Ealing 24. Newham 9. Enfield 25. Redbridge 10. Greenwich 26. Richmond upon Thames 11. Hackney 27. Southwark 12. Hammersmith and Fulham 28. Sutton 13. Haringey 29. Tower Hamlets 14. -

Limits to the Mega-City Region: Contrasting Local and Regional Needs Turok, Ivan

www.ssoar.info Limits to the mega-city region: contrasting local and regional needs Turok, Ivan Postprint / Postprint Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Zur Verfügung gestellt in Kooperation mit / provided in cooperation with: www.peerproject.eu Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Turok, I. (2009). Limits to the mega-city region: contrasting local and regional needs. Regional Studies, 43(6), 845-862. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343400903095261 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter dem "PEER Licence Agreement zur This document is made available under the "PEER Licence Verfügung" gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zum PEER-Projekt finden Agreement ". For more Information regarding the PEER-project Sie hier: http://www.peerproject.eu Gewährt wird ein nicht see: http://www.peerproject.eu This document is solely intended exklusives, nicht übertragbares, persönliches und beschränktes for your personal, non-commercial use.All of the copies of Recht auf Nutzung dieses Dokuments. Dieses Dokument this documents must retain all copyright information and other ist ausschließlich für den persönlichen, nicht-kommerziellen information regarding legal protection. You are not allowed to alter Gebrauch bestimmt. Auf sämtlichen Kopien dieses Dokuments this document in any way, to copy it for public or commercial müssen alle Urheberrechtshinweise und sonstigen Hinweise purposes, to exhibit the document in public, to perform, distribute auf gesetzlichen Schutz beibehalten werden. Sie dürfen dieses or otherwise use the document in public. Dokument nicht in irgendeiner Weise abändern, noch dürfen By using this particular document, you accept the above-stated Sie dieses Dokument für öffentliche oder kommerzielle Zwecke conditions of use. vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, aufführen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. Mit der Verwendung dieses Dokuments erkennen Sie die Nutzungsbedingungen an. -

Diversity Peer Challenge Draft Report

Recovery and Reset Panel Dorset Council th 7 September 2020 Feedback Letter 1. Overview of the approach to the Recovery and Reset Panel with Dorset Council The Local Government Association (LGA) is hugely grateful to Dorset Council for being amongst the first local authorities, and the very first in the South West region, to undertake a Recovery and Reset Panel. This tool, along with a sister model entitled ‘Remote Peer Support’, has been developed to aid councils in their work relating to the Covid-19 crisis and its many and varied impacts. The Panel ran for two hours on the morning of Monday 7th September 2020 and focused on the following: • Digital maturity in recovery – how this has helped the response, support and information to residents and work with partners • Remote working and meetings, embracing new technology, improved decision-making and member-officer relations and impact on governance • Workforce capacity and flexibility, use of ‘Skills Agency’, benefits to employees and impact on service delivery • Determination to continue to innovate, maintain new practice and attitudes Around half a dozen of the council’s senior political and managerial leadership and senior officers in a supporting role were involved and the session was facilitated by the following peers: • Dave Perry, Chief Executive, South Gloucestershire Council • Councillor Alan Jarrett, Leader, Medway Council • Simon Oliver, Director for Digital Transformation, Bristol City Council They were supported by Chris Bowron and Suraiya Khatun from the LGA. The input to the preparations for, and delivery of, the Panel by Sarah Longdon, the council’s Covid-19 Recovery Lead, were very much appreciated by all involved. -

Report for Medway Council

Appendix 2 The Audit Findings (ISA260) report for Medway Council Year ended 31 March 2020 16 November 2020 © 2020 Grant Thornton UK LLP | Audit Findings Report for Medway Council | 2019/20 Contents Section Page 1. Headlines 3 2. Financial statements 7 Your key Grant Thornton team members are: 3. Value for money 24 4. Independence and ethics 32 Darren Wells Key Audit Partner Appendices T: 01293 554 120 E: [email protected] A. Action plan 34 B. Follow up of prior year recommendations 38 Ade Oyerinde C. Audit adjustments 40 Senior Manager T: 020 7728 3332 D. Fees 45 E: [email protected] E. Audit Opinion TBC Nick Halliwell Assistant Manager T: 020 7728 2469 E: [email protected] The contents of this report relate only to those matters which came to our attention during the conduct of our normal audit procedures which are designed for the purpose of expressing our opinion on the financial statements. Our audit is not designed to test all internal controls or identify all areas of control weakness. However, where, as part of our testing, we identify control weaknesses, we will report these to you. In consequence, our work cannot be relied upon to disclose all defalcations or other irregularities, or to include all possible improvements in internal control that a more extensive special examination might identify. This report has been prepared solely for your benefit and should not be quoted in whole or in part without our prior written consent. We do not accept any responsibility for any loss occasioned to any third party acting, or refraining from acting on the basis of the content of this report, as this report was not prepared for, nor intended for, any other purpose. -

Bus Service Improvement Plan (Bsip) 2021-2026

<DRAFT> BUS SERVICE IMPROVEMENT PLAN (BSIP) 2021-2026 SECTION 1 – OVERVIEW 1.1 Context and BSIP extent 1.1.1 This Bus Service Improvement Plan covers the whole of the Medway Council area, for which there will be a single Enhanced Partnership. Fig 1- Location of Medway 1.1.2 It is not intended to cover services which are excluded from the English National Concessionary Travel Scheme, even where these may be registered as local bus services in the Medway area. 1.1.3 We are working collaboratively with our colleagues at Kent County Council, who are producing a BSIP for their own area. However, our plans remain separate for a number of reasons: 1. Only a handful of routes offer inter-urban cross-boundary travel. 2. Although the Medway/Kent boundary cuts through the Lordswood and Walderslade areas, with one exception, services crossing this boundary in the contiguous urban area are effectively short extensions of Medway-focussed routes. 3. Medway is primarily an urban area with a small rural hinterland; Kent is a large rural county with a plethora of widely dispersed urban settlements. 4. Medway's socio-economic make up is considerably different to that of Kent as a whole. It is a lower wage economy, while more than 35% of jobs are in lower skilled categories, compared to under 30% in Kent, and even fewer in the wider south east (source: ONS annual population survey via nomisweb.co.uk). Indices of Multiple Deprivation are much poorer in Medway than in Kent (see appendix 1). 5. As a unitary authority, Medway Council has certain powers that are not available to Kent County Council. -

(Public Pack)Minutes Document for Cabinet, 07/04/2020 15:00

Record of Cabinet decisions Tuesday, 7 April 2020 3.03pm to 3.48pm Date of publication: 8 April 2020 Subject to call-in these decisions will be effective from 20 April 2020 The record of decisions is subject to approval at the next meeting of the Cabinet Present: Councillor Alan Jarrett Leader of the Council Councillor Howard Doe Deputy Leader and Portfolio Holder for Housing and Community Services remote participation Councillor Phil Filmer Portfolio Holder for Front Line Services Councillor Adrian Gulvin Portfolio Holder for Resources Councillor Mrs Josie Iles Portfolio Holder for Children’s Services – Lead Member (statutory responsibility) Councillor Rupert Turpin Portfolio Holder for Business Management In Attendance: Neil Davies, Chief Executive Jade Hannah, Democratic Services Officer Wayne Hemingway, Principal Democratic Services Officer Perry Holmes, Chief Legal Officer/Monitoring Officer Apologies for absence Apologies for absence were received from Councillors David Brake (Portfolio for Adults’ Services), Rodney Chambers OBE (Portfolio Holder for Inward Investment, Strategic Regeneration and Partnerships), Jane Chitty (Portfolio Holder for Planning, Economic Growth and Regulation) and Martin Potter (Education and Schools). Declarations of Disclosable Pecuniary Interests and Other Significant Interests Disclosable pecuniary interests There were none. Cabinet, 7 April 2020 Other significant interests (OSIs) There were none. Other interests There were none. Record of decisions The record of the meeting held on 3 March 2020 was agreed by the Cabinet and signed by the Leader as a correct record. The record of the urgent decision taken by the Leader on 27 March 2020 was agreed by the Cabinet and signed by the Leader as a correct record. -

Your Council Tax

Your council tax We provide more than 140 services Find out inside how your 2020/21 council tax funds them Kent & Medway Get up-to-date news from Medway Council Fi re@medway_council & Rescue Authority 1 Medway Council About your council tax Medway Council, Kent Police and Crime Commissioner and Kent and Medway Fire and Rescue Authority together deliver most of the local services in your area. If you live in an area with a parish council, it too provides some local services. This leafet provides information from each of these authorities. The council tax you pay is collected by Medway Council on behalf of all the above authorities. The total amount is then divided between them (see table on page 4). Kent & Medway Fire & Rescue Authority Did you know Medway’s council tax is the lowest in Kent Get up-to-date news from Medway Council @medway_council 3 Your council tax 2017/18 4 How much will I have to pay? A B C D E F G H £40,001 £52,001 £68,001 Up to £88,001 £120,001 £160,001 £320,001 to to to House banding £40,000 to to to and £52,000 £68,000 £88,000 £120,000 £160,000 £320,000 above Total for Medway residents £1,169.60 £1,364.53 £1,559.47 £1,754.40 £2,144.27 £2,534.13 £2,924.00 £3,508.80 Medway Council £981.31 £1144.86 £1308.41 £1471.96 £1799.06 £2126.16 £2453.27 £2943.92 Kent Police & Crime Commissioner £135.43 £158.01 £180.58 £203.15 £248.29 £293.44 £338.58 £406.30 Kent & Medway Fire & Rescue Authority £52.86 £61.67 £70.48 £79.29 £96.91 £114.53 £132.15 £158.58 If you live in one of the following parishes you have to pay an additional parish -

The Future of Government and Healthcare

The Future of Government and Healthcare SURVEY REPORT 2019 Survey Partner TABLE OF CONTENTS 03 Survey Methodologies 05 Introduction and Respondents Profile 06 16 Key Findings Conclusion Appendix 1: 17 Appendix 2: 25 Survey Questions Participating Organisations 03 INTRODUCTION “By harnessing digital to build and deliver align more closely with the goals of the services, the government can transform the Transformation Strategy as a whole. In relationship between citizen and state.”¹ So particular, the focus is now moving away states the Government Transformation from transforming isolated transactions to Strategy 2017-2020. Yet this is by no means looking at end-to-end services as users an easy journey, as Ben Gummer, the then understand them, including learning to Minister for the Cabinet Office and drive or starting a business, in a bid to Paymaster General notes: design and deliver joined-up services. “Government is more complex and Organisations across the public sector are wide-reaching that ever before. There is no under pressure to adapt and transform with company on earth – even the largest these key areas in mind. With the rise of multinationals – which comes close to technologies such as cloud and automation, having to co-ordinate the array of essential and specific agendas and reports like the services and functions for millions of people NHS Five Year Forward view, adding more that a modern government provides.” fuel, it is vital organisations are able to keep up. Yet while opportunities and benefits are In 2016, a UN report into the development often clear and understood, challenges of e-government technologies ranked the such as security and data protection remain United Kingdom (UK) as the most digitally ever present, and strategies that don’t advanced government globally.² However, consider transformation at every level of the by 2018, the UK had dropped to the fourth organisation – often used as a short-term fix place.