Encounters with Cultures: Contemporary Indian Theatre

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contents SEAGULL Theatre QUARTERLY

S T Q Contents SEAGULL THeatRE QUARTERLY Issue 17 March 1998 2 EDITORIAL Editor 3 Anjum Katyal ‘UNPEELING THE LAYERS WITHIN YOURSELF ’ Editorial Consultant Neelam Man Singh Chowdhry Samik Bandyopadhyay 22 Project Co-ordinator A GATKA WORKSHOP : A PARTICIPANT ’S REPORT Paramita Banerjee Ramanjit Kaur Design 32 Naveen Kishore THE MYTH BEYOND REALITY : THE THEATRE OF NEELAM MAN SINGH CHOWDHRY Smita Nirula 34 THE NAQQALS : A NOTE 36 ‘THE PERFORMING ARTIST BELONGED TO THE COMMUNITY RATHER THAN THE RELIGION ’ Neelam Man Singh Chowdhry on the Naqqals 45 ‘YOU HAVE TO CHANGE WITH THE CHANGING WORLD ’ The Naqqals of Punjab 58 REVIVING BHADRAK ’S MOGAL TAMSA Sachidananda and Sanatan Mohanty 63 AALKAAP : A POPULAR RURAL PERFORMANCE FORM Arup Biswas Acknowledgements We thank all contributors and interviewees for their photographs. 71 Where not otherwise credited, A DIALOGUE WITH ENGLAND photographs of Neelam Man Singh An interview with Jatinder Verma Chowdhry, The Company and the Naqqals are by Naveen Kishore. 81 THE CHALLENGE OF BINGLISH : ANALYSING Published by Naveen Kishore for MULTICULTURAL PRODUCTIONS The Seagull Foundation for the Arts, Jatinder Verma 26 Circus Avenue, Calcutta 700017 86 MEETING GHOSTS IN ORISSA DOWN GOAN ROADS Printed at Vinayaka Naik Laurens & Co 9 Crooked Lane, Calcutta 700 069 S T Q SEAGULL THeatRE QUARTERLY Dear friend, Four years ago, we started a theatre journal. It was an experiment. Lots of questions. Would a journal in English work? Who would our readers be? What kind of material would they want?Was there enough interesting and diverse work being done in theatre to sustain a journal, to feed it on an ongoing basis with enough material? Who would write for the journal? How would we collect material that suited the indepth attention we wanted to give the subjects we covered? Alongside the questions were some convictions. -

Copyright by Kristen Dawn Rudisill 2007

Copyright by Kristen Dawn Rudisill 2007 The Dissertation Committee for Kristen Dawn Rudisill certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: BRAHMIN HUMOR: CHENNAI’S SABHA THEATER AND THE CREATION OF MIDDLE-CLASS INDIAN TASTE FROM THE 1950S TO THE PRESENT Committee: ______________________________ Kathryn Hansen, Co-Supervisor ______________________________ Martha Selby, Co-Supervisor ______________________________ Ward Keeler ______________________________ Kamran Ali ______________________________ Charlotte Canning BRAHMIN HUMOR: CHENNAI’S SABHA THEATER AND THE CREATION OF MIDDLE-CLASS INDIAN TASTE FROM THE 1950S TO THE PRESENT by Kristen Dawn Rudisill, B.A.; A.M. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin December 2007 For Justin and Elijah who taught me the meaning of apu, pācam, kātal, and tuai ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I came to this project through one of the intellectual and personal journeys that we all take, and the number of people who have encouraged and influenced me make it too difficult to name them all. Here I will acknowledge just a few of those who helped make this dissertation what it is, though of course I take full credit for all of its failings. I first got interested in India as a religion major at Bryn Mawr College (and Haverford) and classes I took with two wonderful men who ended up advising my undergraduate thesis on the epic Ramayana: Michael Sells and Steven Hopkins. Dr. Sells introduced me to Wendy Doniger’s work, and like so many others, I went to the University of Chicago Divinity School to study with her, and her warmth compensated for the Chicago cold. -

Scenography Studies – on the Margin of Art History and Theater Studies

Art Inquiry. Recherches sur les arts 2014, vol. XVI ISSN 1641-9278 Dominika Łarionow Department of Art History, University of Łódź [email protected] SCENOGRAPHY STUDIES – ON THE MARGIN OF ART HISTORY AND THEATER STUDIES Abstract: Scenography as a domain of artistic activity has always been a liminal art, placed between the visual arts and theater, with the latter being treated as a chiefly literary domain. The history of scenography to date has recorded two moments when it rose to prominence, becoming the “queen” of the spectacle: the Renaissance and modern times. The article will briefly discuss its history, to show the main reasons for the exclusion of scenography from the domain of academic research. The author will survey some recent publications on set design written by practitioners and academics. Keywords: set design – scenography – history of theater – theater. Scenography as a domain of artistic activity has always been a liminal art, placed between the visual arts and theater, with the latter being treated as a chiefly literary domain. Its roots reach back to the theater of ancient Greece. Even during that period, it was already a marginalized discipline. Aristotle noted in his Poetics, which can be partly regarded as representative for the ideas of his time, that although a spectacle is the work of the skenograph, its significance depends on the craftsmanship of the playwright. Therefore, he acknowledges the quality that scenography contributes to the spectacle, but in order to achieve catharsis, that ancient category associated with the reception of a work of art, a work of great literary value is needed. -

Between Violence and Democracy: Bengali Theatre 1965–75

BETWEEN VIOLENCE AND DEMOCRACY / Sudeshna Banerjee / 1 BETWEEN VIOLENCE AND DEMOCRACY: BENGALI THEATRE 1965–75 SUDESHNA BANERJEE 1 The roots of representation of violence in Bengali theatre can be traced back to the tortuous strands of socio-political events that took place during the 1940s, virtually the last phase of British rule in India. While negotiations between the British, the Congress and the Muslim League were pushing the country towards a painful freedom, accompanied by widespread communal violence and an equally tragic Partition, with Bengal and Punjab bearing, perhaps, the worst brunt of it all; the INA release movement, the RIN Mutiny in 1945-46, numerous strikes, and armed peasant uprisings—Tebhaga in Bengal, Punnapra-Vayalar in Travancore and Telengana revolt in Hyderabad—had underscored the potency of popular movements. The Left-oriented, educated middle class including a large body of students, poets, writers, painters, playwrights and actors in Bengal became actively involved in popular movements, upholding the cause of and fighting for the marginalized and the downtrodden. The strong Left consciousness, though hardly reflected in electoral politics, emerged as a weapon to counter State violence and repression unleashed against the Left. A glance at a chronology of events from October 1947 to 1950 reflects a series of violent repressive measures including indiscriminate firing (even within the prisons) that Left movements faced all over the state. The history of post–1964 West Bengal is ridden by contradictions in the manifestation of the Left in representative politics. The complications and contradictions that came to dominate politics in West Bengal through the 1960s and ’70s came to a restive lull with the Left Front coming to power in 1977. -

Hindi Theater Is Not Seen in Any Other Theatre

NATYA SHODH SANSTHAN DISCUSSION ON HINDI THEATRE FROM THE COLLECTIONS OF NATYA SHODH SANSTHAN AUDIO LIBRARY THE PRESENT SCENARIO OF HINDI THEATRE IN CALCUTTA ON th 15 May 1983 AT NATYA SHODH SANSTHAN PARTICIPANTS PRATIBHA AGRAWAL, SAMIK BANDYOPADHYAY, SHIV KUMAR JOSHI, SHYAMANAND JALAN, MANAMOHON THAKORE SHEO KUMAR JHUNJHUNWALA, SWRAN CHOWDHURY, TAPAS SEN, BIMAL LATH, GAYANWATI LATH, SURESH DUTT, PRAMOD SHROFF NATYA SHODH SANSTHAN EE 8, SECTOR 2, SALT LAKE, KOLKATA 91 MAIL : [email protected] Phone (033)23217667 1 NATYA SHODH SANSTHAN Pratibha Agrawal We are recording the discussion on “The present scenario of the Hindi Theatre in Calcutta”. The participants include – Kishen Kumar, Shymanand Jalan, Shiv Kumar Joshi, Shiv Kumar Jhunjhunwala, Manamohan Thakore1, Samik Banerjee, Dharani Ghosh, Usha Ganguly2 and Bimal Lath. We welcome all of you on behalf of Natya Shodh Sansthan. For quite some time we, the actors, directors, critics and the members of the audience have been appreciating and at the same time complaining about the plays that are being staged in Calcutta in the languages that are being practiced in Calcutta, be it in Hindi, English, Bangla or any other language. We felt that if we, the practitioners should sit down and talk about the various issues that are bothering us, we may be able to solve some of the problems and several issues may be resolved. Often it so happens that the artists take one side and the critics-audience occupies the other. There is a clear division – one group which creates and the other who criticizes. Many a time this proves to be useful and necessary as well. -

List of Empanelled Artist

INDIAN COUNCIL FOR CULTURAL RELATIONS EMPANELMENT ARTISTS S.No. Name of Artist/Group State Date of Genre Contact Details Year of Current Last Cooling off Social Media Presence Birth Empanelment Category/ Sponsorsred Over Level by ICCR Yes/No 1 Ananda Shankar Jayant Telangana 27-09-1961 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-40-23548384 2007 Outstanding Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vwH8YJH4iVY Cell: +91-9848016039 September 2004- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vrts4yX0NOQ [email protected] San Jose, Panama, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YDwKHb4F4tk [email protected] Tegucigalpa, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SIh4lOqFa7o Guatemala City, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MiOhl5brqYc Quito & Argentina https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=COv7medCkW8 2 Bali Vyjayantimala Tamilnadu 13-08-1936 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44-24993433 Outstanding No Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wbT7vkbpkx4 +91-44-24992667 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zKvILzX5mX4 [email protected] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kyQAisJKlVs https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q6S7GLiZtYQ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WBPKiWdEtHI 3 Sucheta Bhide Maharashtra 06-12-1948 Bharatanatyam Cell: +91-8605953615 Outstanding 24 June – 18 July, Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WTj_D-q-oGM suchetachapekar@hotmail 2015 Brazil (TG) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UOhzx_npilY .com https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SgXsRIOFIQ0 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lSepFLNVelI 4 C.V.Chandershekar Tamilnadu 12-05-1935 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44- 24522797 1998 Outstanding 13 – 17 July 2017- No https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ec4OrzIwnWQ -

Prospectus 2020-21

PROSPECTUS 2020-21 Online Registration Fee Category Fee in INR General 600 EWS 550 OBC 400 SC/ST/PWD 275 UNIVERSITY OF HYDERABAD (A Central University established by an Act of Parliament) Visitor The President of India Chief Rector The Governor of Telangana Chancellor Justice L. Narasimha Reddy Vice-Chancellor Prof. Appa Rao Podile Pro Vice-Chancellor- 1 Prof. Arun Agarwal Pro Vice-Chancellor- 2 Prof. B. Raja Shekhar University of Hyderabad Prof. C. R. Rao Road, P.O. Central University, Gachibowli, Hyderabad 500 046, Telangana, (India) University’s EPABX: 040-2313 0000 Page 2 :: PROSPECTUS: 2020-21// UNIVERSITY OF HYDERABAD: INDIA’S INSTITUTION OF EMINENCE WWW.UOHYD.AC.IN Page 3 :: PROSPECTUS: 2020-21// UNIVERSITY OF HYDERABAD: INDIA’S INSTITUTION OF EMINENCE Why University of Hyderabad? Institution of Eminence The Institution of Eminence status accorded by the Government of India to the University of Hyderabad in September 2019 is recognition of the university’s standing, ability and potential to move into the league of the world’s best institutions. With additional funding and autonomy, we are positioned to figure in the World’s 500 Best Universities in the next few years. Excellence in University System The University was previously granted the status of University with Potential for Excellence (UPE) by the University Grants Commission (UGC). The University was sanctioned a grant of Rs.30 crore under UPE Phase-1 for Interfacial Studies & Research and Holistic Development for 5 years (2002- 2007) and Rs.50 crore under the Phase-2 (2012-2016). The Advanced Centre for Research in High Energy Materials (ACRHEM) on the University campus was supported by DRDO for Research on High Energy Materials to the tune of Rs.113 crore in the Phase-3. -

2011 Batch List of Previous Batch Students.Xlsx

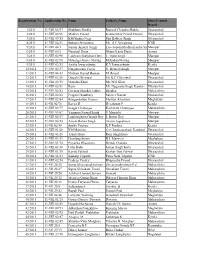

Registration_No Application No. Name Father's Name State/Central Board 1/2011 11-VIII 02/97 Shubham Shukla Ramesh Chandra Shukla Uttaranchal 2/2011 11-VIII 02/96 Madhav Prasad Kamleshwar Prasad Painuli Uttaranchal 3/2011 11-VIII 03/15 KM Shikha Negi Shri Balbeer Singh Uttaranchal 4/2011 11-VIII 04/21 Suhasni Srivastava Mr. S.C Srivastava ICSE 5/2011 11-VIII 04/3 Sapam Amarjit Singh Late Sapam Modhuchandra SinghManipur 6/2011 11-VIII 04/2 Nurutpal Dutta Ghana Kanta Dutta Assam 7/2011 11-VIII 02/98 Laishram Bidyabati Devi L. Bijen Singh Manipur 8/2011 11-VIII 02/90 Makunga Joysee Maring M.Kodun Maring Manipur 9/2011 11-VIII 02/33 Anitha Iswarankutty K.V Iswarankutty Kerala 10/2011 11-VIII 02/37 Ningthoujam Victor N. Hemajit Singh Manipur 11/2011 11-VIII 04/13 Maibam Kamal Hassan M. Iboyal Manipur 12/2011 11-VIII 03/28 Dinesh Chhimwal Mr B.C Chhimwal Uttaranchal 13/2011 11-VIII 03/35 Manisha Khati Mr. M.S Khati Uttaranchal 14/2011 11-VIII 02/81 Rajni Mr. Nagendra Singh Kandari Uttaranchal 15/2011 11-VIII 02/82 Gajanan Shankar Jadhav Shankar Maharashtra 16/2011 11-VIII 02/83 Pragati Chaudhary Sanjeev Kumar Uttaranchal 17/2011 11-VIII 02/84 Ritngenbahun Hoojon Markus Kharbhoi Meghalaya 18/2011 11-VII 02/76 Kavya D Devadasan P Kerala 19/2011 11-VIII 02/77 Sougat Chatterjee Kashinath Chatterjee Maharashtra 20/2011 11-VIII 02/67 Yumnam Nirmal Singh Y Manaobi Manipur 21/2011 11-VIII 04/17 Laiphangbam Gunajit Roy L Iboton Roy Manipur 22/2011 11-VIII 04/14 Amom Rohen Singh Amom Jugeshwor Manipur 23/2011 11-VII 02/48 Sruthy Poulose K P Poulose Kerala -

Catalogue Fair Timings

CATALOGUE Fair Timings 28 January 2016 Thursday Select Preview: 12 - 3pm By invitation Preview: 3 - 5pm By invitation Vernissage: 5 - 9pm IAF VIP Card holders (Last entry at 8.30pm) 29 - 30 January 2016 Friday and Saturday Business Hours: 11am - 2pm Public Hours: 2 - 8pm (Last entry at 7.30pm) 31 January 2016 Sunday Public Hours: 11am - 7pm (Last entry at 6.30pm) India Art Fair Team Director's Welcome Neha Kirpal Zain Masud Welcome to our 2016 edition of India Art Fair. Founding Director International Director Launched in 2008 and anticipating its most rigorous edition to date Amrita Kaur Srijon Bhattacharya with an exciting programme reflecting the diversity of the arts in Associate Fair Director Director - Marketing India and the region, India Art Fair has become South Asia's premier and Brand Development platform for showcasing modern and contemporary art. For our 2016 Noelle Kadar edition, we are delighted to present BMW as our presenting partner VIP Relations Director and JSW as our associate partner, along with continued patronage from our preview partner, Panerai. Saheba Sodhi Vishal Saluja Building on its success over the past seven years, India Art Senior Manager - Marketing General Manager - Finance Fair presents a refreshed, curatorial approach to its exhibitor and Alliances and Operations programming with new and returning international participants Isha Kataria Mankiran Kaur Dhillon alongside the best programmes from the subcontinent. Galleries, Vip Relations Manager Programming and Client Relations will feature leading Indian and international exhibitors presenting both modern and contemporary group shows emphasising diverse and quality content. Focus will present select galleries and Tanya Singhal Wol Balston organisations showing the works of solo artists or themed exhibitions. -

Http//:Daathvoyagejournal.Com Editor: Saikat Banerjee Department Of

http//:daathvoyagejournal.com Editor: Saikat Banerjee Department of English Dr. K.N. Modi University, Newai, Rajasthan, India. : An International Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies in English ISSN 2455-7544 www.daathvoyagejournal.com Vol.2, No.3, September, 2017 From Hamlet To Hemlat: Rewriting Shakespeare In Bengal Dr. Mahuya Bhaumik Assistant Professor Department of English Derozio Memorial College, Kolkata, Bengal. Abstract: Production of Shakespeare’s plays in India, particularly Bengal, has an extensive history which dates back to the mid 18th century. Theatre was a tool employed by the British to expose the elites of the Indian society to Western culture and values. Shakespeare was one of the most popular dramatists to be produced in colonial India for concrete reasons. During the latter half of the nineteenth century the productions of Shakespearean plays were marked by a tendency for indigenization thus adding colour colours to them. The latest adaptations of Shakespeare into Bangla are instances of real bold steps taken by the playwrights since these adaptations implant the master text in a completely different politico-cultural milieu, thus subverting the source text in the process. This paper would try to analyse such a process of rewriting Shakespeare in Bangla with special emphasis on Bratya Basu’s Hemlat, The Prince of Garanhata which is an adaptation of Shakespeare’s Hamlet. Key Words: Theatre, Performance, Adaptation, Indigenization, Cross-Culture. Production of Shakespeare’s plays in India, particularly Bengal, has an extensive and rich history which dates back to the mid 18th century. Initially the target audience of these plays was British officials settled here during the colonial days. -

Minutes of the Meeting of the Expert Committee Held on 14Th, 15Th,17Th and 18Th October, 2013 Under the Performing Arts Grants Scheme (PAGS)

No.F.10-01/2012-P.Arts (Pt.) Ministry of Culture P. Arts Section Minutes of the Meeting of the Expert Committee held on 14th, 15th,17th and 18th October, 2013 under the Performing Arts Grants Scheme (PAGS). The Expert Committee for the Performing Arts Grants Scheme (PAGS) met on 14th, 15th ,17thand 18th October, 2013 to consider renewal of salary grants to existing grantees and decide on the fresh applications received for salary and production grants under the Scheme, including review of certain past cases, as recommended in the earlier meeting. The meeting was chaired by Smt. Arvind Manjit Singh, Joint Secretary (Culture). A list of Expert members present in the meeting is annexed. 2. On the opening day of the meeting ie. 14th October, inaugurating the meeting, Sh. Sanjeev Mittal, Joint Secretary, introduced himself to the members of Expert Committee and while welcoming the members of the committee informed that the Ministry was putting its best efforts to promote, develop and protect culture of the country. As regards the Performing Arts Grants Scheme(earlier known as the Scheme of Financial Assistance to Professional Groups and Individuals Engaged for Specified Performing Arts Projects; Salary & Production Grants), it was apprised that despite severe financial constraints invoked by the Deptt. Of Expenditure the Ministry had ensured a provision of Rs.48 crores for the Repertory/Production Grants during the current financial year which was in fact higher than the last year’s budgetary provision. 3. Smt. Meena Balimane Sharma, Director, in her capacity as the Member-Secretary of the Expert Committee, thereafter, briefed the members about the salient features of various provisions of the relevant Scheme under which the proposals in question were required to be examined by them before giving their recommendations. -

Download (5.2

c m y k c m y k Registered with the Registrar of Newspapers of India: Regd. No. 14377/57 CONTRIBUTORS Dr. Karan Singh Gouranga Dash Madhavilatha Ganji Meena Naik Prof. S. A. Krishnaiah Sampa Ghosh Satish C. Mehta Usha Mailk Utpal K Banerjee Indian Council for Cultural Relations Hkkjrh; lkaLdfrd` lEca/k ifj”kn~ Phone: 91-11-23379309, 23379310, 23379314, 23379930 Fax: 91-11-23378639, 23378647, 23370732, 23378783, 23378830 E-mail: [email protected] Web Site: www.iccrindia.net c m y k c m y k c m y k c m y k Indian Council for Cultural Relations The Indian Council for Cultural Relations (ICCR) was founded on 9th April 1950 by Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, the first Education Minister of independent India. The objectives of the Council are to participate in the formulation and implementation of policies and programmes relating to India’s external cultural relations; to foster and strengthen cultural relations and mutual understanding between India and other countries; to promote cultural exchanges with other countries and people; to establish and develop relations with national and international organizations in the field of culture; and to take such measures as may be required to further these objectives. The ICCR is about a communion of cultures, a creative dialogue with other nations. To facilitate this interaction with world cultures, the Council strives to articulate and demonstrate the diversity and richness of the cultures of India, both in and with other countries of the world. The Council prides itself on being a pre-eminent institution engaged in cultural diplomacy and the sponsor of intellectual exchanges between India and partner countries.