Behavioral Ecology of Mobile Animals: Insights from in Situ Observations David B

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Retail Stores Policies for Marketing of Lobsters in Sardinia (Italy) As Influenced by Different Practices Related to Animal Welf

foods Article Retail Stores Policies for Marketing of Lobsters in Sardinia (Italy) as Influenced by Different Practices Related to Animal Welfare and Product Quality Giuseppe Esposito 1, Daniele Nucera 2 and Domenico Meloni 1,* ID 1 Department of Veterinary Medicine, University of Sassari, Via Vienna 2, 07100 Sassari, Italy; [email protected] 2 Department of Agriculture, Forest and Food Science, University of Turin, Via Verdi 8, 10124 Turin, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +39-079-229-570; Fax: +39-079-229-458 Received: 12 June 2018; Accepted: 29 June 2018; Published: 2 July 2018 Abstract: The aim of the present study was to evaluate the marketing policies of lobsters as influenced by different practices related to product quality in seven supermarkets located in Italy. Retailers were divided in two categories: large scale and medium scale. The two groups were compared to screen for differences and to assess differences in score distribution attributed to different practices related to product quality. Our results showed no statistical differences (p > 0.05) between the two categories. Lobsters were often marketed alive on ice and/or stocked for long periods in supermarket aquariums, highlighting the need to improve the specific European regulations on health, welfare, and quality at the market stage. Retail shop managers should be encouraged to develop better practices and policies in terms of marketing of lobsters. This will help in keeping the animals in good health and improve product quality at the marketing stages. Keywords: crustaceans; supermarkets; aquarium; ice 1. Introduction In the last decades, the global total consumption of seafood products has increased: this has resulted in a rapidly growing demand for these products, especially in emerging markets [1]. -

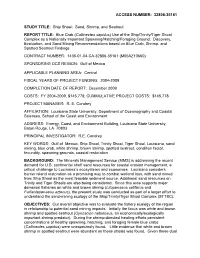

Blue Crab (Callinectes Sapidus) Use of the Ship/Trinity/Tiger Shoal

ACCESS NUMBER: 32806-35161 STUDY TITLE: Ship Shoal: Sand, Shrimp, and Seatrout REPORT TITLE: Blue Crab (Callinectes sapidus) Use of the Ship/Trinity/Tiger Shoal Complex as a Nationally Important Spawning/Hatching/Foraging Ground: Discovery, Evaluation, and Sand Mining Recommendations based on Blue Crab, Shrimp, and Spotted Seatrout Findings CONTRACT NUMBER: 1435-01-04-CA-32806-35161 (M05AZ10660) SPONSORING OCS REGION: Gulf of Mexico APPLICABLE PLANNING AREA: Central FISCAL YEARS OF PROJECT FUNDING: 2004-2009 COMPLETION DATE OF REPORT: December 2009 COSTS: FY 2004-2009, $145,778; CUMMULATIVE PROJECT COSTS: $145,778 PROJECT MANAGER: R. E. Condrey AFFILIATION: Louisiana State University, Department of Oceanography and Coastal Sciences, School of the Coast and Environment ADDRESS: Energy, Coast, and Environment Building, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA 70803 PRINCIPAL INVESTIGATOR: R.E. Condrey KEY WORDS: Gulf of Mexico, Ship Shoal, Trinity Shoal, Tiger Shoal, Louisiana, sand mining, blue crab, white shrimp, brown shrimp, spotted seatrout, condition factor, fecundity, spawning grounds, coastal restoration BACKGROUND: The Minerals Management Service (MMS) is addressing the recent demand for U.S. continental shelf sand resources for coastal erosion management, a critical challenge to Louisiana’s ecosystems and economies. Louisiana considers barrier island restoration as a promising way to combat wetland loss, with sand mined from Ship Shoal as the most feasible sediment source. Additional sand resources on Trinity and Tiger Shoals are also being considered. Since this area supports major demersal fisheries on white and brown shrimp (Litopenaeus setiferus and Farfantepenaeus aztecus), the present study was conducted as part of a larger effort to understand the sand-mining ecology of the Ship/Trinity/Tiger Shoal Complex (STTSC). -

Dimorphism and the Functional Basis of Claw Strength in Six Brachyuran Crabs

J. Zool., Lond. (2001) 255, 105±119 # 2001 The Zoological Society of London Printed in the United Kingdom Dimorphism and the functional basis of claw strength in six brachyuran crabs Steve C. Schenk1 and Peter C. Wainwright2 1 Department of Biological Science, Florida State University, Tallahassee, Florida 32306, U.S.A. 2 Section of Evolution and Ecology, University of California, Davis, CA 95616, U.S.A. (Accepted 7 November 2000) Abstract By examining the morphological basis of force generation in the chelae (claws) of both molluscivorous and non-molluscivorous crabs, it is possible to understand better the difference between general crab claw design and the morphology associated with durophagy. This comparative study investigates the mor- phology underlying claw force production and intraspeci®c claw dimorphism in six brachyuran crabs: Callinectes sapidus (Portunidae), Libinia emarginata (Majidae), Ocypode quadrata (Ocypodidae), Menippe mercenaria (Xanthidae), Panopeus herbstii (Xanthidae), and P. obesus (Xanthidae). The crushers of the three molluscivorous xanthids consistently proved to be morphologically `strong,' having largest mechan- ical advantages (MAs), mean angles of pinnation (MAPs), and physiological cross-sectional areas (PCSAs). However, some patterns of variation (e.g. low MA in C. sapidus, indistinguishable force generation potential in the xanthids) suggested that a quantitative assessment of occlusion and dentition is needed to understand fully the relationship between force generation and diet. Interspeci®c differences in force generation potential seemed mainly to be a function of differences in chela closer muscle cross- sectional area, due to a sixfold variation in apodeme area. Intraspeci®c dimorphism was generally de®ned by tall crushers with long in-levers, though O. -

Chinese Mitten Crab (Eriocheir Sinensis)

www.nonnativespecies.org For definitive identification, contact: [email protected] Chinese mitten crab (Eriocheir sinensis) Synonyms: - big sluiceway crab, Chinese freshwater edible crab, Chinese mittenhanded crab, Chinese mit- ten-handed crab, Chinese river crab, crabe chi- nois, mitten crab, river crab, Shanghai crab, villus crab - Eriocheir japonicas, E. leptognathus, E. rectus Consignments likely to come from: unknown Use: may be used for human consumption Identification difficulty: easy Identification information: - the only freshwater crab present in Britain - body (carapace) olive-green-brown, up to 8cm wide - pincers covered in a mat of fine hair resembling mittens - legs long and hairy Key ID Features Pincers covered in a mat Body (carapace) olive- of fine hair, giving the green-brown, up to 8 cm appearance of mittens wide Up to 8 cm Legs long and hairy Male and female Chinese mitten crabs are similar in appearance except their undersides Underside Underside of female of male Similar species Three other crab species are commonly imported to Britain but these are unlikely to be confused with Chinese mitten crab. Eriocheir sinensis Metacarcinus magister (Chinese mitten crab) (Dungeness crab) for comparison Body up tp to 8cm Legs long across and hairy Body up tp to 25cm across, usually under 20cm Body beige to light brown in Body (carapace) olive- Pincers covered in a mat colour with blue edges green-brown of fine hair, giving the appearance of mittens Callinectes sapidus Portunus pelagicus (Atlantic blue crab) (blue swimmer crab) Legs blue, body greyish / Body up tp to 27cm Vary in colour from dark Body up tp to 21cm greenish brown across brown, blue and purple across Pair of long, pointed Paddle shaped rear legs spines at lateral edges Paddle shaped rear legs of body Photos from: Almandine, Children’s Museum of Indianapolis, Dan Boone—United States Fish and Wildlife Service (all via Wikimedia Commons), & APHA . -

A New Pathogenic Virus in the Caribbean Spiny Lobster Panulirus Argus from the Florida Keys

DISEASES OF AQUATIC ORGANISMS Vol. 59: 109–118, 2004 Published May 5 Dis Aquat Org A new pathogenic virus in the Caribbean spiny lobster Panulirus argus from the Florida Keys Jeffrey D. Shields1,*, Donald C. Behringer Jr2 1Virginia Institute of Marine Science, The College of William & Mary, Gloucester Point, Virginia 23062, USA 2Department of Biological Sciences, Old Dominion University, Norfolk, Virginia 23529, USA ABSTRACT: A pathogenic virus was diagnosed from juvenile Caribbean spiny lobsters Panulirus argus from the Florida Keys. Moribund lobsters had characteristically milky hemolymph that did not clot. Altered hyalinocytes and semigranulocytes, but not granulocytes, were observed with light microscopy. Infected hemocytes had emarginated, condensed chromatin, hypertrophied nuclei and faint eosinophilic Cowdry-type-A inclusions. In some cases, infected cells were observed in soft con- nective tissues. With electron microscopy, unenveloped, nonoccluded, icosahedral virions (182 ± 9 nm SD) were diffusely spread around the inner periphery of the nuclear envelope. Virions also occurred in loose aggregates in the cytoplasm or were free in the hemolymph. Assembly of the nucleocapsid occurred entirely within the nucleus of the infected cells. Within the virogenic stroma, blunt rod-like structures or whorls of electron-dense granular material were apparently associated with viral assembly. The prevalence of overt infections, defined as lethargic animals with milky hemolymph, ranged from 6 to 8% with certain foci reaching prevalences of 37%. The disease was transmissible to uninfected lobsters using inoculations of raw hemolymph from infected animals. Inoculated animals became moribund 5 to 7 d before dying and they began dying after 30 to 80 d post-exposure. -

Growth Rate Variability and Lipofuscin Accumulation Rates in the Blue Crab Callinectes Sapidus

MARINE ECOLOGY PROGRESS SERIES Vol. 224: 197–205, 2001 Published December 19 Mar Ecol Prog Ser Growth rate variability and lipofuscin accumulation rates in the blue crab Callinectes sapidus Se-Jong Ju, David H. Secor, H. Rodger Harvey* Chesapeake Biological Laboratory, University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science, PO Box 38, Solomons, Maryland 20688, USA ABSTRACT: To better understand growth and age-pigment (lipofuscin) accumulation rates of the blue crab Callinectes sapidus under natural conditions, juveniles (33 to 94 mm carapace width) were reared in outdoor ponds for over 1 yr. Growth rates, measured by carapace width, during summer and fall exceeded all those reported in the literature; the initial carapace width of 59 ± 14 mm (mean ± SD) increased to 164 ± 15 mm within a 3 mo period. No growth occurred during winter months (Novem- ber to April) at low water temperatures. Growth rates of crabs in ponds were substantially higher (von Bertalanffy growth parameter K = 1.09) than those of crabs held in laboratory environments, and than rate estimates for natural populations of mid-Atlantic blue crabs. Model comparisons indicated that seasonalized von Bertalanffy growth models (r2 > 0.9) provide a better fit than the non-seasonalized model (r2 = 0.74) for pond-reared crabs and, by implication, are more appropriate for field popula- tions. Despite growth rates that varied strongly with season, lipofuscin (normalized to protein con- centration) accumulation rate was nearly constant throughout the year. Although the lipofuscin level in pond-reared crabs was significantly correlated with size (carapace width), it was more closely cor- related with chronological age. -

Blue Crab. U.S

~C' k""~-- - -- - S..- - _ __ - -. .54.5 .tS-'--------- - - - -tt Coastal Ecology Group Fish and Wildlife Service . Waterways Experiment Station U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Army Corps of Engineers c-ýz N7cw jo r ýs Biological Report 82(11.100) TR EL-82-4 March 1989 Species Profiles: Life Histories and Environmental Requirements of Coastal Fishes and Invertebrates (Mid-Atlantic) BLUE CRAB by Jennifer Hill, Dean L. Fowler, and Michael J. Van Den Avyle Georgia Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit School of Forest Resources University of Georgia Athens, GA 30602 Project Officer David Moran U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service National Wetlands Research Center 1010 Gause Boulevard Slidell, LA 70458 Performed for U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Coastal Ecology Group Waterways Experiment Station Vicksburg, MS 39180 and U.S. Department of the Interior Fish and Wildlife Service Research and Development National Wetlands Research Center Washington, DC 20240 DISCLAIMER The mention of trade nanes in this report does not constitute endorsement nor recommendation for use by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service or Federal Government. This series may be referenced as follows: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1983-19 Species profiles: life histories and environmental requirements of coastail fishes and invertebrates. U.S. Fish Wildl. Serv. Biol. Rep. 82(11). U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, TR EL-82-4. This profile may be cited as follows: Hill, J., D.L. Fowler, and M.J. Van Den Avyle. 1989. Species profiles: life histories and environmental requirements of coastal fishes and invertebrates (Mid-Atlantic)--Blue crab. -

An Evaluation of the Effects of Blue Crab (Callinectes Sapidus) Behavior on the Efficacy of Abcr Pots As a Tool for Estimating Population Abundance

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by College of William & Mary: W&M Publish W&M ScholarWorks VIMS Articles 2011 An Evaluation Of The Effects Of Blue Crab (Callinectes Sapidus) Behavior On The Efficacy Of abCr Pots As A Tool For Estimating Population Abundance Samuel Kersey Sturdivant Virginia Institute of Marine Science KL Clark Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/vimsarticles Part of the Aquaculture and Fisheries Commons Recommended Citation Sturdivant, Samuel Kersey and Clark, KL, "An Evaluation Of The Effects Of Blue Crab (Callinectes Sapidus) Behavior On The Efficacy Of abCr Pots As A Tool For Estimating Population Abundance" (2011). VIMS Articles. 552. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/vimsarticles/552 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in VIMS Articles by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 48 Abstract—Crab traps have been used An evaluation of the effects extensively in studies on the popula- tion dynamics of blue crabs to provide of blue crab (Callinectes sapidus) estimates of catch per unit of effort; however, these estimates have been behavior on the efficacy of crab pots determined without adequate consid- as a tool for estimating population abundance eration of escape rates. We examined the ability of the blue crab (Callinectes sapidus) to escape crab pots and the S. Kersey Sturdivant (contact author)1 possibility that intraspecific crab Kelton L. Clark2 interactions have an effect on catch rates. -

11 Shields FISH 98(1)

139 Abstract.–On the eastern seaboard of Mortality and hematology of blue crabs, the United States, populations of the blue crab, Callinectes sapidus, experi- Callinectes sapidus, experimentally infected ence recurring outbreaks of a parasitic dinoflagellate, Hematodinium perezi. with the parasitic dinoflagellate Epizootics fulminate in summer and autumn causing mortalities in high- Hematodinium perezi* salinity embayments and estuaries. In laboratory studies, we experimentally investigated host mortality due to the Jeffrey D. Shields disease, assessed differential hemato- Christopher M. Squyars logical changes in infected crabs, and Department of Environmental Sciences examined proliferation of the parasite. Virginia Institute of Marine Science Mature, overwintering, nonovigerous The College of William and Mary female crabs were injected with 103 or P.O. Box 1346, Gloucester Point, VA 23602, USA 105 cells of H. perezi. Mortalities began E-mail address (for J. D. Shields): [email protected] 14 d after infection, with a median time to death of 30.3 ±1.5 d (SE). Sub- sequent mortality rates were greater than 86% in infected crabs. A relative risk model indicated that infected crabs were seven to eight times more likely to Hematodinium perezi is a parasitic larger, riverine (“bayside”) fishery; die than controls and that decreases in total hemocyte densities covaried signif- dinoflagellate that proliferates in it appears most detrimental to the icantly with mortality. Hemocyte densi- the hemolymph of several crab spe- coastal (“seaside”) crab fisheries. ties declined precipitously (mean=48%) cies. In the blue crab, Callinectes Outbreaks of infestation by Hema- within 3 d of infection and exhibited sapidus, H. perezi is highly patho- todinium spp. -

Spider Crab (Maja Spp.)

Spider crab (Maja spp.) Summary 200 mm male Size (carapace length) 175 mm female (Pawson, 1995) ~ 6 years male Lifespan ~ 5 years female (Gonçalves et al., 2020) Size of maturity (CL₅₀) 52 -137 mm Fecundity >6000 eggs (size dependent) (Baklouti et al., 2015) Reproductive frequency Annual Capture methods Pots and nets Fishing Season All year round Description Four species of spider crab belonging to the genus Maja inhabit European coasts: M.brachydactyla, M.crispata, M.goltziana, and M.squinado (Sotelo et al., 2009). Until fairly recently the main commercial species caught in Atlantic waters was assumed to be M.squinado. However, Neumann (1998) suggested that Atlantic and Mediterranean populations of M.squinado were distinct species based on morphological and biometric characters and concluded M.squinado in the Atlantic were in fact M.brachydactyla. Genetic analysis has since supported the recognition of two separate species with M.squinado restricted to the Mediterranean (Sotelo et al., 2009). M.brachydactyla is distributed in the eastern Atlantic from the western Sahara in the south to the southern British Isles in the north, including the Azores and Canary Islands (d’Udekem d’Acoz, 1999 cited in Abelló et al., 2014). It is most abundant at depths between 0-70 m, although it has been recorded at 120 m (Pawson, 1995). This species of spider crab can be found on most seabed types and scavenges food including carrion, encrusting animals, and seaweed. M.brachydactyla is known as the common spider crab but it might also be referred to as, the spinous, spiny, or European spider crab (names also used for M.squinado). -

Prevalence of Blue Crab (Callinectes Sapidus) Diseases, Parasites, And

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2014 Prevalence of Blue Crab (Callinectes sapidus) Diseases, Parasites, and Symbionts in Louisiana Holly Rogers Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Environmental Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Rogers, Holly, "Prevalence of Blue Crab (Callinectes sapidus) Diseases, Parasites, and Symbionts in Louisiana" (2014). LSU Master's Theses. 3071. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/3071 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PREVALENCE OF BLUE CRAB (CALLINECTES SAPIDUS) DISEASES, PARASITES, AND SYMBIONTS IN LOUISIANA A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in The School of Renewable Natural Resources by Holly A. Rogers B.S., University of Cincinnati, 2011 August 2014 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my major professor, Dr. Julie Anderson, for selecting me for this assistantship and research project and for teaching more than I ever wanted to know about blue crabs. I would also like to thank Dr. Bill Kelso for his advice and instruction, particularly on scientific writing. I owe thanks to Dr. John Hawke for his guidance on crab and aquatic diseases and Dr. Sabrina Taylor for her helpful PCR advice. -

Characterization of Larval Moulting Cycles in Maja Brachydactyla (Brachyura

1 1 Characterization of larval moulting cycles in Maja brachydactyla (Brachyura, 2 Majidae) reared in the laboratory 3 4 Guillermo Gueraoa*, Guiomar Rotllanta, Klaus Angerb 5 6 aIRTA, Unitat de Cultius Experimentals. Ctra. Poble Nou, Km 5.5, 43540 Sant Carles de la Ràpita, 7 Tarragona, Spain. 8 bAlfred-Wegener-Institut für Polar- und Meeresforschung; Biologische Anstalt Helgoland, 9 Meeresstation, 27498 Helgoland, Germany. 10 11 * Corresponding author: E-mail address: [email protected] (G. Guerao) 12 Fax: +34-977 74 41 38 13 14 Abstract 15 16 The moulting cycles of all larval instars (zoea I, zoea II, megalopa) of the spider crab Maja 17 brachydactyla Balss 1922 were studied in laboratory rearing experiments. Morphological changes in 18 the epidermis and cuticle were photographically documented in daily intervals and assigned to 19 successive stages of the moulting cycle (based on Drach’s classification system). Our moult-stage 20 characterizations are based on microscopical examination of integumental modifications mainly in 21 the telson, using epidermal condensation, the degree of epidermal retraction (apolysis), and 22 morphogenesis (mainly setagenesis) as criteria. In the zoea II and megalopa, the formation of new 23 setae was also observed in larval appendages including the antenna, maxillule, maxilla, second 24 maxilliped, pleopods, and uropods. As principal stages within the zoea I moulting cycle, we describe 25 postmoult (Drach’s stages A-B combined), intermoult (C), and premoult (D), the latter with three 26 substages (D0, D1, D2). In the zoea II and megalopa, D0 and D1 had to be combined, because 27 morphogenesis (the main characteristic of D1) was unclear in the telson and did not occur 28 synchronically in different appendices.