Spider Crab (Maja Spp.)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Retail Stores Policies for Marketing of Lobsters in Sardinia (Italy) As Influenced by Different Practices Related to Animal Welf

foods Article Retail Stores Policies for Marketing of Lobsters in Sardinia (Italy) as Influenced by Different Practices Related to Animal Welfare and Product Quality Giuseppe Esposito 1, Daniele Nucera 2 and Domenico Meloni 1,* ID 1 Department of Veterinary Medicine, University of Sassari, Via Vienna 2, 07100 Sassari, Italy; [email protected] 2 Department of Agriculture, Forest and Food Science, University of Turin, Via Verdi 8, 10124 Turin, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +39-079-229-570; Fax: +39-079-229-458 Received: 12 June 2018; Accepted: 29 June 2018; Published: 2 July 2018 Abstract: The aim of the present study was to evaluate the marketing policies of lobsters as influenced by different practices related to product quality in seven supermarkets located in Italy. Retailers were divided in two categories: large scale and medium scale. The two groups were compared to screen for differences and to assess differences in score distribution attributed to different practices related to product quality. Our results showed no statistical differences (p > 0.05) between the two categories. Lobsters were often marketed alive on ice and/or stocked for long periods in supermarket aquariums, highlighting the need to improve the specific European regulations on health, welfare, and quality at the market stage. Retail shop managers should be encouraged to develop better practices and policies in terms of marketing of lobsters. This will help in keeping the animals in good health and improve product quality at the marketing stages. Keywords: crustaceans; supermarkets; aquarium; ice 1. Introduction In the last decades, the global total consumption of seafood products has increased: this has resulted in a rapidly growing demand for these products, especially in emerging markets [1]. -

Preliminary Mass-Balance Food Web Model of the Eastern Chukchi Sea

NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-AFSC-262 Preliminary Mass-balance Food Web Model of the Eastern Chukchi Sea by G. A. Whitehouse U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration National Marine Fisheries Service Alaska Fisheries Science Center December 2013 NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS The National Marine Fisheries Service's Alaska Fisheries Science Center uses the NOAA Technical Memorandum series to issue informal scientific and technical publications when complete formal review and editorial processing are not appropriate or feasible. Documents within this series reflect sound professional work and may be referenced in the formal scientific and technical literature. The NMFS-AFSC Technical Memorandum series of the Alaska Fisheries Science Center continues the NMFS-F/NWC series established in 1970 by the Northwest Fisheries Center. The NMFS-NWFSC series is currently used by the Northwest Fisheries Science Center. This document should be cited as follows: Whitehouse, G. A. 2013. A preliminary mass-balance food web model of the eastern Chukchi Sea. U.S. Dep. Commer., NOAA Tech. Memo. NMFS-AFSC-262, 162 p. Reference in this document to trade names does not imply endorsement by the National Marine Fisheries Service, NOAA. NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-AFSC-262 Preliminary Mass-balance Food Web Model of the Eastern Chukchi Sea by G. A. Whitehouse1,2 1Alaska Fisheries Science Center 7600 Sand Point Way N.E. Seattle WA 98115 2Joint Institute for the Study of the Atmosphere and Ocean University of Washington Box 354925 Seattle WA 98195 www.afsc.noaa.gov U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE Penny. S. Pritzker, Secretary National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Kathryn D. -

Temporal Trends of Two Spider Crabs (Brachyura, Majoidea) in Nearshore Kelp Habitats in Alaska, U.S.A

TEMPORAL TRENDS OF TWO SPIDER CRABS (BRACHYURA, MAJOIDEA) IN NEARSHORE KELP HABITATS IN ALASKA, U.S.A. BY BENJAMIN DALY1,3) and BRENDA KONAR2,4) 1) University of Alaska Fairbanks, School of Fisheries and Ocean Sciences, 201 Railway Ave, Seward, Alaska 99664, U.S.A. 2) University of Alaska Fairbanks, School of Fisheries and Ocean Sciences, P.O. Box 757220, Fairbanks, Alaska 99775, U.S.A. ABSTRACT Pugettia gracilis and Oregonia gracilis are among the most abundant crab species in Alaskan kelp beds and were surveyed in two different kelp habitats in Kachemak Bay, Alaska, U.S.A., from June 2005 to September 2006, in order to better understand their temporal distribution. Habitats included kelp beds with understory species only and kelp beds with both understory and canopy species, which were surveyed monthly using SCUBA to quantify crab abundance and kelp density. Substrate complexity (rugosity and dominant substrate size) was assessed for each site at the beginning of the study. Pugettia gracilis abundance was highest in late summer and in habitats containing canopy kelp species, while O. gracilis had highest abundance in understory habitats in late summer. Large- scale migrations are likely not the cause of seasonal variation in abundances. Microhabitat resource utilization may account for any differences in temporal variation between P. gracilis and O. gracilis. Pugettia gracilis may rely more heavily on structural complexity from algal cover for refuge with abundances correlating with seasonal changes in kelp structure. Oregonia gracilis mayrelyonkelp more for decoration and less for protection provided by complex structure. Kelp associated crab species have seasonal variation in habitat use that may be correlated with kelp density. -

Larval Rearing of Mithraculus Sculptus (Lamarck, 1818) in Captivity

UNIVERSIDADE DO ALGARVE Faculdade de Ciências e Tecnologia Larval rearing of Mithraculus sculptus (Lamarck, 1818) in captivity. Tiago Miguel Dionísio Mourinho Dissertação apresentada para obtenção de Grau de Mestre em Aquacultura e Pescas-Especialidade em Aquacultura Trabalho efectuado sob orientação de: Prof. Dra. Margarida Cristo Mestre Joana Salabert 2012 UNIVERSIDADE DO ALGARVE Faculdade de ciências e tecnologia Larval rearing of Mithraculus sculptus (Lamarck, 1818) in captivity. Dissertação orientada por: Prof. Dra. Margarida Cristo Universidade do Algarve Faculdade de Ciências e Tecnologia Dissertação co-orientada por: Mestre Joana Salabert Lusoreef, Criação de Espécies Marinhas, Lda. Autor: Lic. Tiago Miguel Dinísio Mourinho Universidade do Algarve Faculdade de Ciências e Tecnologia Mestrado em Aquacultura e Pescas-Especialidade em Aquacultura 2012 Larval rearing of Mithraculus sculptus (Lamarck, 1818) in captivity. Declaração de autoria de trabalho Declaro ser o autor deste trabalho, que é original e inédito. Autores e trabalhos consultados estão devidamente citados no texto e constam da listagem de referências incluída. O autor: Tiago Mourinho Copyright® by Tiago Mourinho A Universidade do Algarve tem o direito, perpétuo e sem limites geográficos, de arquivar e publicitar este trabalho através de exemplares impressos reproduzidos em papel ou de forma digital, ou por qualquer outro meio conhecido ou que venha a ser inventado, de o divulgar através de repositórios científicos e de admitir a sua cópia e distribuição com objetivos educacionais ou de investigação, não comerciais, desde que seja dado crédito ao autor e editor. Resumo O aumento exponencial da aquariofilia de recife tem levantado alguns problemas ecológicos. A captura de seres vivos dos recifes para o mercado aquarista tem impactos negativos na ecologia dos mesmos. -

For Review Only 19 20 21 504 Ampuero D, T

Page 1 of 39 Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 1 2 3 1 DNA identification and larval morphology provide new evidence on the systematic 4 5 2 position of Ergasticus clouei A. Milne-Edwards, 1882 (Decapoda, Brachyura, 6 7 3 Majoidea) 8 9 10 4 11 1 2 1 3 12 5 Marco-Herrero, Elena , Torres, Asvin P. , Cuesta, José A. , Guerao, Guillermo , Palero, 13 14 6 Ferran 4, & Abelló, Pere 5 15 16 7 17 18 8 1Instituto de CienciasFor Marinas Review de Andalucía (ICMAN-C OnlySIC), Avda. República 19 20 21 9 Saharaui, 2, 11519 Puerto Real, Cádiz, Spain. 22 2 23 10 Instituto Español de Oceanografía, Centre Oceanogràfic de les Balears, Moll de Ponent 24 25 11 s/n, 07015 Palma, Spain. 26 27 12 3IRTA, Unitat de Cultius Aqüàtics. Ctra. Poble Nou, Km 5.5, 43540 Sant Carles de la 28 29 30 13 Ràpita, Tarragona, Spain. 31 4 32 14 Unitat Mixta Genòmica i Salut CSISP-UV, Institut Cavanilles Universitat de Valencia, 33 34 15 C/ Catedrático José Beltrán 2, 46980 Paterna, Spain. 35 36 16 5Institut de Ciències del Mar (CSIC), Passeig Marítim de la Barceloneta 37-49, 08003 37 38 17 Barcelona, Catalonia. Spain. 39 40 41 18 42 43 19 44 45 20 46 47 21 RUN TITLE: Larval evidence and the systematic position of Ergasticus clouei 48 49 50 22 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society Page 2 of 39 1 2 3 23 ABSTRACT: The morphology of the complete larval stage series of the crab Ergasticus 4 5 24 clouei is described and illustrated based on larvae (zoea I, zoea II and megalopa) 6 7 25 captured from plankton samples taken in Mediterranean waters. -

Distribution, Abundance, and Diversity of Epifaunal Benthic Organisms in Alitak and Ugak Bays, Kodiak Island, Alaska

DISTRIBUTION, ABUNDANCE, AND DIVERSITY OF EPIFAUNAL BENTHIC ORGANISMS IN ALITAK AND UGAK BAYS, KODIAK ISLAND, ALASKA by Howard M. Feder and Stephen C. Jewett Institute of Marine Science University of Alaska Fairbanks, Alaska 99701 Final Report Outer Continental Shelf Environmental Assessment Program Research Unit 517 October 1977 279 We thank the following for assistance during this study: the crew of the MV Big Valley; Pete Jackson and James Blackburn of the Alaska Department of Fish and Game, Kodiak, for their assistance in a cooperative benthic trawl study; and University of Alaska Institute of Marine Science personnel Rosemary Hobson for assistance in data processing, Max Hoberg for shipboard assistance, and Nora Foster for taxonomic assistance. This study was funded by the Bureau of Land Management, Department of the Interior, through an interagency agreement with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Department of Commerce, as part of the Alaska Outer Continental Shelf Environment Assessment Program (OCSEAP). SUMMARY OF OBJECTIVES, CONCLUSIONS, AND IMPLICATIONS WITH RESPECT TO OCS OIL AND GAS DEVELOPMENT Little is known about the biology of the invertebrate components of the shallow, nearshore benthos of the bays of Kodiak Island, and yet these components may be the ones most significantly affected by the impact of oil derived from offshore petroleum operations. Baseline information on species composition is essential before industrial activities take place in waters adjacent to Kodiak Island. It was the intent of this investigation to collect information on the composition, distribution, and biology of the epifaunal invertebrate components of two bays of Kodiak Island. The specific objectives of this study were: 1) A qualitative inventory of dominant benthic invertebrate epifaunal species within two study sites (Alitak and Ugak bays). -

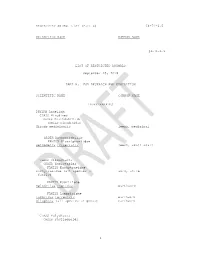

RESTRICTED ANIMAL LIST (Part A) §4-71-6.5 SCIENTIFIC NAME

RESTRICTED ANIMAL LIST (Part A) §4-71-6.5 SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME §4-71-6.5 LIST OF RESTRICTED ANIMALS September 25, 2018 PART A: FOR RESEARCH AND EXHIBITION SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME INVERTEBRATES PHYLUM Annelida CLASS Hirudinea ORDER Gnathobdellida FAMILY Hirudinidae Hirudo medicinalis leech, medicinal ORDER Rhynchobdellae FAMILY Glossiphoniidae Helobdella triserialis leech, small snail CLASS Oligochaeta ORDER Haplotaxida FAMILY Euchytraeidae Enchytraeidae (all species in worm, white family) FAMILY Eudrilidae Helodrilus foetidus earthworm FAMILY Lumbricidae Lumbricus terrestris earthworm Allophora (all species in genus) earthworm CLASS Polychaeta ORDER Phyllodocida 1 RESTRICTED ANIMAL LIST (Part A) §4-71-6.5 SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME FAMILY Nereidae Nereis japonica lugworm PHYLUM Arthropoda CLASS Arachnida ORDER Acari FAMILY Phytoseiidae Iphiseius degenerans predator, spider mite Mesoseiulus longipes predator, spider mite Mesoseiulus macropilis predator, spider mite Neoseiulus californicus predator, spider mite Neoseiulus longispinosus predator, spider mite Typhlodromus occidentalis mite, western predatory FAMILY Tetranychidae Tetranychus lintearius biocontrol agent, gorse CLASS Crustacea ORDER Amphipoda FAMILY Hyalidae Parhyale hawaiensis amphipod, marine ORDER Anomura FAMILY Porcellanidae Petrolisthes cabrolloi crab, porcelain Petrolisthes cinctipes crab, porcelain Petrolisthes elongatus crab, porcelain Petrolisthes eriomerus crab, porcelain Petrolisthes gracilis crab, porcelain Petrolisthes granulosus crab, porcelain Petrolisthes -

Characterization of Larval Moulting Cycles in Maja Brachydactyla (Brachyura

1 1 Characterization of larval moulting cycles in Maja brachydactyla (Brachyura, 2 Majidae) reared in the laboratory 3 4 Guillermo Gueraoa*, Guiomar Rotllanta, Klaus Angerb 5 6 aIRTA, Unitat de Cultius Experimentals. Ctra. Poble Nou, Km 5.5, 43540 Sant Carles de la Ràpita, 7 Tarragona, Spain. 8 bAlfred-Wegener-Institut für Polar- und Meeresforschung; Biologische Anstalt Helgoland, 9 Meeresstation, 27498 Helgoland, Germany. 10 11 * Corresponding author: E-mail address: [email protected] (G. Guerao) 12 Fax: +34-977 74 41 38 13 14 Abstract 15 16 The moulting cycles of all larval instars (zoea I, zoea II, megalopa) of the spider crab Maja 17 brachydactyla Balss 1922 were studied in laboratory rearing experiments. Morphological changes in 18 the epidermis and cuticle were photographically documented in daily intervals and assigned to 19 successive stages of the moulting cycle (based on Drach’s classification system). Our moult-stage 20 characterizations are based on microscopical examination of integumental modifications mainly in 21 the telson, using epidermal condensation, the degree of epidermal retraction (apolysis), and 22 morphogenesis (mainly setagenesis) as criteria. In the zoea II and megalopa, the formation of new 23 setae was also observed in larval appendages including the antenna, maxillule, maxilla, second 24 maxilliped, pleopods, and uropods. As principal stages within the zoea I moulting cycle, we describe 25 postmoult (Drach’s stages A-B combined), intermoult (C), and premoult (D), the latter with three 26 substages (D0, D1, D2). In the zoea II and megalopa, D0 and D1 had to be combined, because 27 morphogenesis (the main characteristic of D1) was unclear in the telson and did not occur 28 synchronically in different appendices. -

Interactions of the Fishery of the Spider Crab Maja Squinado with Mating, Reproductive Biology and Migrations

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Repositorio da Universidade da Coruña 1 Interactions of the fishery of the spider crab Maja squinado with mating, reproductive biology and migrations Juan Freire, Luis Fernández and Eduardo González-Gurriarán Freire, J., Fernández, L. and González-Gurriarán, E. Interactions of the fishery of the spider crab Maja squinado with mating, reproductive biology and migrations. ICES Journal of Marine Science. In this paper different aspects of the fishery and life history of the spider crab Maja squinado in southern Galicia (NW Spain) are analyzed to evaluate the potential effects of the fishery on the sperm limitation of the reproductive effort (egg production) of the population. Juveniles of the spider crab inhabit shallow waters (<15 m), where they carry out a terminal moult in August-September, attaining sexual maturity when they are 2+ years old. A short time after the terminal moult (October-November), adults migrate to deeper waters (up to 100 m), where mating occurs (January-February). Field and laboratory data show that multiple matings and sperm storage in female seminal receptacles occur, indicating that females are able to fertilize multiple broods during the annual breeding cycle using stored sperm. The spider crab is the target of a tangle-net fishery, characterized by a very high fishing effort similar for both sexes. The fishing season is from November-December until May-June and is mostly dependent on migrating animals. Data from catch composition (percentage of recent recruits at the beginning of the season), recaptures from the fishery of females tagged with ultrasonic transmitters and electronic archival tags, and CPUE trends over the course of the fishing season (Leslie analyses of stock depletion) indicate that more than 90% of postpubertal (primiparous) adults are caught during the fishing season. -

Feeding of the Spider Crab Maja Squinado in Rocky Subtidal Areas of the R|¨A De Arousa (North-West Spain)

J. Mar. Biol. Ass. U.K. (2000), 80, 95^102 Printed in the United Kingdom Feeding of the spider crab Maja squinado in rocky subtidal areas of the R|¨a de Arousa (north-west Spain) C. Berna¨ rdez, J. Freire* and E. Gonza¨ lez-Gurriara¨ n Departamento de Biolox|¨a Animal, Biolox|¨aVexetal e Ecolox|¨a, Universidade da Corun¬ a, Campus da Zapateira s/n, 15071 A Corun¬ a, Spain. *E-mail: [email protected] The diet of the spider crab, Maja squinado, was studied in the rocky subtidal areas of the R|¨a de Arousa (Galicia, north-west Spain), by analysing the gut contents of crabs caught in the summer and winter of 1992. The highly diverse diet was made up primarily of macroalgae and benthic invertebrates that were either sessile or had little mobility. The most important prey were the seaweeds Laminariaceae (43% of the frequency of occurrence and 15% of the food dry weight), Corallina spp. (38% and 3%), molluscs [the chiton Acanthochitona crinitus (15% and 1%), the gastropods Bittium sp. (30% and 2%),Trochiidae and others and the bivalve Mytilus sp. (32% and 12%)], echinoderms [the holothurian Aslia lefevrei (32% and 18%) and the echi- noid Paracentrotus lividus (16% and 7%)] and solitary ascidians (18% and 6%). The variability in diet composition was determined by the season (Laminariaceae, Corallina spp., P. lividus, Mytilus sp., gastropods and chitons appeared in greater frequency in winter, while the solitary ascidians and A. lefevrei were consumed to a greater extent in summer) in addition to sexual maturity (prey such as Bittium sp. -

The Perception of Diplopoda (Arthropoda, Myriapoda) by the Inhabitants of the County of Pedra Branca, Santa Teresinha, Bahia, Brazil

Acta biol. Colomb., Vol. 12 No. 2, 2007 123 - 134 THE PERCEPTION OF DIPLOPODA (ARTHROPODA, MYRIAPODA) BY THE INHABITANTS OF THE COUNTY OF PEDRA BRANCA, SANTA TERESINHA, BAHIA, BRAZIL La percepción de diplopoda (Arthropoda, Myriapoda) por los habitantes del poblado de Pedra Branca, Santa Teresinha, Bahía, Brasil ERALDO M. COSTA NETO1, Ph. D. 1Universidade Estadual de Feira de Santana, Departamento de Ciências Biológicas, Laboratório de Etnobiologia, Km 03, BR 116, Campus Universitário, CEP 44031-460, Feira de Santana, Bahia, Brasil Fone/Fax: 75 32248019. [email protected] Presentado 30 de junio de 2006, aceptado 5 de diciembre 2006, correcciones 22 de mayo de 2007. ABSTRACT This paper deals with the conceptions, knowledge and attitudes of the inhabitants of the county of Pedra Branca, Bahia State, on the arthropods of the class Diplopoda. Data were collected from February to June 2005 by means of open-ended interviews carried out with 28 individuals, which ages ranged from 13 to 86 years old. It was recorded some traditional knowledge regarding the following items: taxonomy, biology, habitat, ecology, seasonality, and behavior. Results show that the diplopods are classified as “insects”. The characteristic of coiling the body was the most com- mented, as well as the fact that these animals are considered as “poisonous”. In gen- eral, the traditional zoological knowledge of Pedra Branca’s inhabitants concerning the diplopods is coherent with the academic knowledge. Key words: Ethnozoology, ethnomyriapodology, perception, millipede. RESUMEN Este artículo registra las concepciones, los conocimientos y los comportamientos que los habitantes del poblado de Pedra Branca, en el estado de Bahía, poseen sobre los artrópodos de la clase Diplopoda. -

Identification of European Species of Maja (Decapoda: Brachyura: Majidae): RFLP Analyses of COI Mtdna and Morphological Considerations

Scientia Marina 75(1) March 2011, 129-134, Barcelona (Spain) ISSN: 0214-8358 doi: 10.3989/scimar.2011.75n1129 Identification of European species of Maja (Decapoda: Brachyura: Majidae): RFLP analyses of COI mtDNA and morphological considerations GUILLERMO GUERAO 1, KARL B. ANDREE 1, CARLO FROGLIA 2, CARLES G. SIMEÓ 1 and GUIOMAR ROTLLANT 1 1 IRTA, Unitat Operativa de Cultius Aquàtics, Ctra. Poble Nou, Km 5.5, 43540 Sant Carles de la Ràpita, Tarragona, Spain. E-mail: [email protected] 2 Istituto di Scienze Marine (CNR), Largo Fiera della Pesca, 60125 Ancona, Italia. SUMMARY: Four species of crabs of the genus Maja have been described along the European coast: M. brachydactyla, M. squinado, M. goltziana and M. crispata. The commercially important species M. brachydactyla and M. squinado achieve the largest body sizes and are the most similar in morphology, and are therefore easily confused. The four species of Maja were identified using a novel morphometric index and a polymerase chain reaction followed by restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis (RFLP). The relationship between carapace length and the distance between the tips of antorbital spines was used to distinguish adults of M. brachydactyla and M. squinado. PCR-RFLP analysis of a partial sequence of the mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase type I (COI) revealed that the four species of the genus Maja can be unambiguously discriminated using the combination of restriction endonucleases enzymes HpyCH4V and Ase I. The molecular identifica- tion may be particularly useful in larvae, juvenile and young crabs, when the morphological differences found in adults are not applicable. Keywords: Maja, M.