Resource Limitation and Population Ecology Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

War and the White Rhinos

War and the White Rhinos Kai Curry-Lindahl Until 1963 the main population of the northern square-lipped (white) rhino was in the Garamba National Park, in the Congo (now Zaire) where they had increased to over 1200. That year armed rebels occupied the park, and when three years later they had been driven out, the rhinos had been drastically reduced: numbers were thought to be below 50. Dr. Curry-Iindahl describes what he found in 1966 and 1967. The northern race of the square-lipped rhinoceros Ceratotherium simum cottoni was once widely distributed in Africa north of the equator, but persecution has exterminated it over large areas. It is now known to occur only in south-western Sudan, north-eastern Congo (Kinshasa) and north-western Uganda. It is uncertain whether it still exists in northern Ubangui, in the Central African Republic. In the Sudan, where for more than ten years its range has been affected by war and serious disturbances, virtually nothing is known of its present status. In Uganda numbers dropped from about 350 in 1955 to 80 in 1962 and about 20-25 in 1969 (Cave 1963, Simon 1970); the twelve introduced into the Murchison Falls National Park in 1960, despite two being poached, increased to 18 in 1971. But the bulk of the population before 1963 was in the Garamba National Park in north-eastern Congo, in the Uele area. There, since 1938, it had been virtually undisturbed, and, thanks to the continuous research which characterised the Congo national parks before 1960, population figures are known for several periods (see the Table on page 264). -

Animals of Africa

Silver 49 Bronze 26 Gold 59 Copper 17 Animals of Africa _______________________________________________Diamond 80 PYGMY ANTELOPES Klipspringer Common oribi Haggard oribi Gold 59 Bronze 26 Silver 49 Copper 17 Bronze 26 Silver 49 Gold 61 Copper 17 Diamond 80 Diamond 80 Steenbok 1 234 5 _______________________________________________ _______________________________________________ Cape grysbok BIG CATS LECHWE, KOB, PUKU Sharpe grysbok African lion 1 2 2 2 Common lechwe Livingstone suni African leopard***** Kafue Flats lechwe East African suni African cheetah***** _______________________________________________ Red lechwe Royal antelope SMALL CATS & AFRICAN CIVET Black lechwe Bates pygmy antelope Serval Nile lechwe 1 1 2 2 4 _______________________________________________ Caracal 2 White-eared kob DIK-DIKS African wild cat Uganda kob Salt dik-dik African golden cat CentralAfrican kob Harar dik-dik 1 2 2 African civet _______________________________________________ Western kob (Buffon) Guenther dik-dik HYENAS Puku Kirk dik-dik Spotted hyena 1 1 1 _______________________________________________ Damara dik-dik REEDBUCKS & RHEBOK Brown hyena Phillips dik-dik Common reedbuck _______________________________________________ _______________________________________________African striped hyena Eastern bohor reedbuck BUSH DUIKERS THICK-SKINNED GAME Abyssinian bohor reedbuck Southern bush duiker _______________________________________________African elephant 1 1 1 Sudan bohor reedbuck Angolan bush duiker (closed) 1 122 2 Black rhinoceros** *** Nigerian -

Kalinzu to Queen Elizabeth National Park Days 3

For this tour we meet up late afternoon the day prior to departure at the Red Chilli Hideaway, in Kampala, by Lake Victoria for our predeparture meeting. We then enjoy a meal UGANDA KENYA together and get to know the other travellers in the group. You Kampala Jinja Queen Elizabeth ✈ can camp with the truck this evening, or alternatively we can Chimps Mt Kenya The Virungas Equator arrange a dorm bed or a room at this well run hostel. The hostel Kisoro Masai Mara Mountain Gorillas ✈Lake is set in beautiful gardens and has a swimming pool. Musanze Kigali Victoria RWANDA Serengeti Nairobi Day 1: Kampala to Kalinzu, Uganda Ngorongoro Crater Kilimanjaro DEMOCRATIC Arusha Diani Beach Leaving early this morning heading for Mbarara, we make stops REPUBLIC OF Lake Tanganika at curio markets and on the Equator for breakfast and a photo CONGO ✈ TANZANIA Zanzibar shoot. On the way we pass tea plantations, wetlands of papyrus, Island and rice fields as we travel along the Albertine Rift, part of the Dar Es Salaam Great Rift Valley. We spend the night at a camp on the edge of Kalinzu Forest. Key Distance: 355 kms THE ROUTE Est. Drive Time: +/- 8 hours incl. stops at highlights such as the GAME PARK ADD ON Jinja & The White Nile Equator, for shopping and lunch ADD ON Masai Mara (✈ flight required) Meals: X1 Breakfast, X1 Dinner ADD ON Zanzibar Island (✈ flight required) Day 2: Kalinzu to Queen Elizabeth National Park There is the option to trek habituated chimpanzees in Kalinzu Forest this morning. In this beautiful evergreen forest six Distance, Day 3: 218 kms different species of primate can be identified including blue Distance, Day 4: 75 kms monkeys, vervet monkeys, black and white colobus monkeys Est. -

Influence of Industrial Activities on the Spatial Distribution of Wildlife in Murchison Falls National Park, Uganda

University of Rhode Island DigitalCommons@URI Open Access Master's Theses 2011 INFLUENCE OF INDUSTRIAL ACTIVITIES ON THE SPATIAL DISTRIBUTION OF WILDLIFE IN MURCHISON FALLS NATIONAL PARK, UGANDA Samuel Ayebare University of Rhode Island, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/theses Recommended Citation Ayebare, Samuel, "INFLUENCE OF INDUSTRIAL ACTIVITIES ON THE SPATIAL DISTRIBUTION OF WILDLIFE IN MURCHISON FALLS NATIONAL PARK, UGANDA" (2011). Open Access Master's Theses. Paper 112. https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/theses/112 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@URI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@URI. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFLUENCE OF INDUSTRIAL ACTIVITIES ON THE SPATIAL DISTRIBUTION OF WILDLIFE IN MURCHISON FALLS NATIONAL PARK, UGANDA BY SAMUEL AYEBARE A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCE UNIVERSITY OF RHODE ISLAND 2011 MASTER OF SCIENCE THESIS OF SAMUEL AYEBARE APPROVED: Thesis Committee: Major Professor: Yeqiao Wang Peter Paton Peter August Howard Ginsberg Nasser H. Zawia DEAN OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL UNIVERSITY OF RHODE ISLAND 2011 ABSTRACT Activities carried out by resource extraction industries in and adjacent to protected areas have increased the risk to biodiversity conservation in different parts of the world. Oil and natural gas developments in the Albertine rift, one of Africa’s biodiversity hotspots, have raised concerns about the potential impacts to wildlife populations and the associated land-cover change. The influence of oil and gas industrial activities on the spatial distribution of wildlife in Murchison Falls National Park was examined by conducting wildlife surveys along 2-km long transects that radiated away from well pads and access roads. -

Records of Exotics Scoring Manual

RECORDS OF EXOTICS SCORING MANUAL SCORER INFORMATION RECORDS OF EXOTICS was started in the late 1970's by Thompson Temple, to assist hunters in evaluating trophy quality of introduced animals in North America. A record book is being produced about every 3 years. Membership is not required to enter an exotic animal in the R.O.E. record keeping system. Animals that meet or exceed the minimum scores will be listed in our next record book with a $20.00 entry fee. Animals may be scored by one of our over 400 designated scorers throughout the United States. Upon acceptance, the entrant will also receive a beautiful certificate suitable for framing to acknowledge their accomplishment. Depending on the score, all entries qualifying may purchase a bronze, silver, or gold medal on an attractive plaque for a modest fee. Various groupings of exotic animals taken are called "slams". Very nice, inexpensive wildlife bronzes are available for purchase to recognize the hunter's accomplishments. Since 1980, the largest exotics for the previous year have been recognized at our annual banquet. We notify hunters by mail if they qualify to win one of our awards for the best exotics of the year. The beauty of the Records of Exotics scoring systems is its simplicity. The first time scorer can measure quickly and accurately, and the scorer is paid a $5.00 scoring fee for each entry. The hunter or scorer may send the accurately completed scoresheet to R.O.E. along with a $20.00 entry fee. The R.O.E. office maintains the scorers records for the year and issues one payment check annually for all scores submitted. -

Accounting for Intraspecific Variation Transforms Our Understanding of Artiodactyl Social Evolution

ACCOUNTING FOR INTRASPECIFIC VARIATION TRANSFORMS OUR UNDERSTANDING OF ARTIODACTYL SOCIAL EVOLUTION By Monica Irene Miles Loren D. Hayes Hope Klug Associate Professor of UC Foundation Associate Professor of Biology, Geology, and Environmental Science Biology, Geology, and Environmental Science (Chair) (Committee Member) Timothy Gaudin UC Foundation Professor of Biology, Geology, and Environmental Science (Committee Member) ACCOUNTING FOR INTRASPECIFIC VARIATION TRANSFORMS OUR UNDERSTANDING OF ARTIODACTYL SOCIAL EVOLUTION By Monica Irene Miles A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Degree of Master of Science: Environmental Science The University of Tennessee at Chattanooga Chattanooga, Tennessee December 2018 ii Copyright © 2018 By Monica Irene Miles All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT A major goal in the study of mammalian social systems has been to explain evolutionary transitions in social traits. Recent comparative analyses have used phylogenetic reconstructions to determine the evolution of social traits but have omitted intraspecific variation in social organization (IVSO) and mating systems (IVMS). This study was designed to summarize the extent of IVSO and IVMS in Artiodactyla and Perissodactyla, and determine the ancestral social organization and mating system for Artiodactyla. Some 82% of artiodactyls showed IVSO, whereas 31% exhibited IVMS; 80% of perissodactyls had variable social organization and only one species showed IVMS. The ancestral population of Artiodactyla was predicted to have variable social organization (84%), rather than solitary or group-living. A clear ancestral mating system for Artiodactyla, however, could not be resolved. These results show that intraspecific variation is common in artiodactyls and perissodactyls, and suggest a variable ancestral social organization for Artiodactyla. -

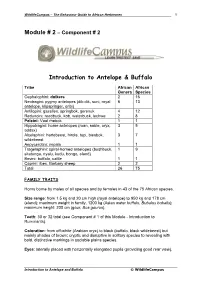

Introduction to Antelope & Buffalo

WildlifeCampus – The Behaviour Guide to African Herbivores 1 Module # 2 – Component # 2 Introduction to Antelope & Buffalo Tribe African African Genera Species Cephalophini: duikers 2 16 Neotragini: pygmy antelopes (dik-dik, suni, royal 6 13 antelope, klipspringer, oribi) Antilopini: gazelles, springbok, gerenuk 4 12 Reduncini: reedbuck, kob, waterbuck, lechwe 2 8 Peleini: Vaal rhebok 1 1 Hippotragini: horse antelopes (roan, sable, oryx, 3 5 addax) Alcelaphini: hartebeest, hirola, topi, biesbok, 3 7 wildebeest Aepycerotini: impala 1 1 Tragelaphini: spiral-horned antelopes (bushbuck, 1 9 sitatunga, nyalu, kudu, bongo, eland) Bovini: buffalo, cattle 1 1 Caprini: ibex, Barbary sheep 2 2 Total 26 75 FAMILY TRAITS Horns borne by males of all species and by females in 43 of the 75 African species. Size range: from 1.5 kg and 20 cm high (royal antelope) to 950 kg and 178 cm (eland); maximum weight in family, 1200 kg (Asian water buffalo, Bubalus bubalis); maximum height: 200 cm (gaur, Bos gaurus). Teeth: 30 or 32 total (see Component # 1 of this Module - Introduction to Ruminants). Coloration: from off-white (Arabian oryx) to black (buffalo, black wildebeest) but mainly shades of brown; cryptic and disruptive in solitary species to revealing with bold, distinctive markings in sociable plains species. Eyes: laterally placed with horizontally elongated pupils (providing good rear view). Introduction to Antelope and Buffalo © WildlifeCampus WildlifeCampus – The Behaviour Guide to African Herbivores 2 Scent glands: developed (at least in males) in most species, diffuse or absent in a few (kob, waterbuck, bovines). Mammae: 1 or 2 pairs. Horns. True horns consist of an outer sheath composed mainly of keratin over a bony core of the same shape which grows from the frontal bones. -

African Animal Checklist

© 2016 AfricaFreak.com African Animal Checklist Species Scientific Name Tick Observations Aardvark Orycteropus afer Aardwolf Proteles cristatus Antelope - Roan Hippotragus equinus Antelope - Sable Hippotragus niger Baboon - Chacma Papio ursinus Baboon - Olive Papio anubis Baboon - Yellow Papio cynocephalus Blesbok Damaliscus dorcas phillipsi Bongo Tragelaphus euryceros Bontebok Damaliscus dorcas dorcas Buffalo - African (Cape) Syncerus caffer Bushbaby - Lesser Galago moholi Bushbaby - Thick-tailed Otolemur crassicaudatus Bushbuck Tragelaphus scriptus Bushpig Potamochoerus porcus Caracal Felis caracal Cat - African Wild Felis lybica Cat - Small Spotted Felis nigripes Cheetah Acinonyx jubatus Chimpanzee Pan troglodytes Civet - African Civettictis civetta Colobus - Black & White Colobus guereza/angolensis Crocodile - Nile Crocodylus niloticus Dik-Dik - Kirk's Madoqua kirkii Dog - Wild (Hunting Dog) Lycaon pictus Duiker - Blue Philantomba monticola Duiker - Common Sylvicapra grimmia Duiker - Red Cephalophus natalensis Eland Taurotragus oryx Elephant Loxodonta africana Fox - Bat-eared Otocyon megalotis Fox - Cape Vulpes chama Gazelle - Grant's Gazella granti Gazelle - Thomson's Gazella thomsoni Gemsbok Oryx gazella Genet - Large-spotted Genetta tigrina Genet - Small-spotted Genetta genetta Gerenuk Litocranius walleri Giraffe - Masai (Maasai) Giraffa c. tippelskirchi Giraffe - Reticulated Giraffa c. reticulata Giraffe - Rothschild's Giraffa c. rothschildi Giraffe - Thornicroft Giraffa c. thornicrofti Gorilla - Lowland Gorilla gorilla graueri -

Mixed-Species Exhibits with Pigs (Suidae)

Mixed-species exhibits with Pigs (Suidae) Written by KRISZTIÁN SVÁBIK Team Leader, Toni’s Zoo, Rothenburg, Luzern, Switzerland Email: [email protected] 9th May 2021 Cover photo © Krisztián Svábik Mixed-species exhibits with Pigs (Suidae) 1 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................... 3 Use of space and enclosure furnishings ................................................................... 3 Feeding ..................................................................................................................... 3 Breeding ................................................................................................................... 4 Choice of species and individuals ............................................................................ 4 List of mixed-species exhibits involving Suids ........................................................ 5 LIST OF SPECIES COMBINATIONS – SUIDAE .......................................................... 6 Sulawesi Babirusa, Babyrousa celebensis ...............................................................7 Common Warthog, Phacochoerus africanus ......................................................... 8 Giant Forest Hog, Hylochoerus meinertzhageni ..................................................10 Bushpig, Potamochoerus larvatus ........................................................................ 11 Red River Hog, Potamochoerus porcus ............................................................... -

The Relationship Between Social Status and Reproductive Activity in Male Impala, Aepyceros Melampus

THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN SOCIAL STATUS AND REPRODUCTIVE ACTIVITY IN MALE IMPALA, AEPYCEROS MELAMPUS P. S. BRAMLEY and W. B. NEAVES Departments of Animal Physiology and Anatomy, University of Nairobi, P.O. Box 30197, Nairobi, Kenya (Received 28th August 1971, accepted \3th November 1971) Summary. The reproductive activity of territorial and bachelor impala was compared. Mean bulbourethral gland weights and plasma testos- terone levels were significantly higher in territorial males and were approximately twice that observed in bachelor males. The other para- meters measured were similar in both social classes. The high testosterone levels in territorial males were probably a result of their territorial status and consequent sexual activity rather than a cause of it. INTRODUCTION Studies of the behaviour of many species of mammals and birds have shown that social status is an important factor in determining whether an individual breeds and, if so, how successfully. Wild populations of animals are frequently divided into territory-holding individuals, which usually breed successfully, and non-territorial individuals, which generally breed unsuccessfully or not at all (Watson & Moss, 1970). There seems to be a positive correlation between social status and reproductive activity in many of the vertebrates which have so far been studied. Information regarding the relationship of sex hormones to social status and sexual behaviour is conflicting. Studies on the male red grouse, Lagopus lagopus, have shown that aggression (and hence, social status) and sexual activity are both controlled by androgens (Watson, 1970). On the other hand, testosterone implants in Uganda kob, Adenota kob, and roe deer, Capreolus capreolus, did not change their behaviour (Leuthold, 1966; Bramley, 1970), but a testosterone implant in a castrated male red deer, Cervus elaphus, resulted in rutting behaviour and a rise in the male hierarchy (Lincoln, Youngson & Short, 1970). -

And Hartebeest (Alcelaphus Buselaphus Jacksoni) (Artiodactyla) from Sub- Saharan Africa, with Further Ruminations on the Ostertagiinae

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications from the Harold W. Manter Laboratory of Parasitology Parasitology, Harold W. Manter Laboratory of 6-2009 Robustostrongylus aferensis gen. nov. et sp. nov. (Nematoda: Trichostrongyloidea) in Kob (Kobus kob) and Hartebeest (Alcelaphus buselaphus jacksoni) (Artiodactyla) from Sub- saharan Africa, with Further Ruminations on the Ostertagiinae Eric P. Hoberg United States Department of Agriculture, [email protected] Arthur Abrams United States Department of Agriculture Patricia A. Pilitt United States Department of Agriculture Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/parasitologyfacpubs Part of the Parasitology Commons Hoberg, Eric P.; Abrams, Arthur; and Pilitt, Patricia A., "Robustostrongylus aferensis gen. nov. et sp. nov. (Nematoda: Trichostrongyloidea) in Kob (Kobus kob) and Hartebeest (Alcelaphus buselaphus jacksoni) (Artiodactyla) from Sub-saharan Africa, with Further Ruminations on the Ostertagiinae" (2009). Faculty Publications from the Harold W. Manter Laboratory of Parasitology. 322. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/parasitologyfacpubs/322 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Parasitology, Harold W. Manter Laboratory of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications from the Harold W. Manter Laboratory of Parasitology by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. J. Parasitol., -

1912 EA Update Report

East Africa Programme UPDATE REPORT August – December 2019 Background The Giraffe Conservation Foundation (GCF) East Africa office, based in Nairobi, was established to increase collaborative efforts with government institutions, private stakeholders, along with local and international NGOs with respect to giraffe conservation and management. In 2019, the office expanded and now has a regional base in Uganda to help increase support related to our efforts across the country. The East African region is critical for the long-term survival of wild populations of giraffe as it is home to three distinct species: Masai giraffe (Giraffa tippelskirchi), reticulated giraffe (G. reticulata) and Nubian giraffe (G. camelopardalis camelopardalis) – all of them threatened with extinction in the wild. This report highlights the steps and programmes that GCF has initiated towards conserving the three species in the region from August to December 2019. Broad-ranging programmes In August 2019, giraffe were added to Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade of Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). This listing comes at a time when the East (and Central) African region has seen steep declines in giraffe populations (in contrast to Southern Africa were numbers continue to increase) with both the Masai and reticulated giraffe added as ‘Endangered’ to the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species in the last year. While this listing does not ban the trade in giraffe parts entirely, it increases the need to track, monitor and regulate this trade internationally. Unfortunately, CITES does not monitor illegal domestic trade of giraffe parts, and evidence of illegal activities across East (and Central) Africa suggests that there are markets and local demand for giraffe products within the region.