Actin Stress Fibers – Assembly, Dynamics and Biological Roles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Snapshot: Formins Christian Baarlink, Dominique Brandt, and Robert Grosse University of Marburg, Marburg 35032, Germany

SnapShot: Formins Christian Baarlink, Dominique Brandt, and Robert Grosse University of Marburg, Marburg 35032, Germany Formin Regulators Localization Cellular Function Disease Association DIAPH1/DIA1 RhoA, RhoC Cell cortex, Polarized cell migration, microtubule stabilization, Autosomal-dominant nonsyndromic deafness (DFNA1), myeloproliferative (mDia1) phagocytic cup, phagocytosis, axon elongation defects, defects in T lymphocyte traffi cking and proliferation, tumor cell mitotic spindle invasion, defects in natural killer lymphocyte function DIAPH2 Cdc42 Kinetochore Stable microtubule attachment to kinetochore for Premature ovarian failure (mDia3) chromosome alignment DIAPH3 Rif, Cdc42, Filopodia, Filopodia formation, removing the nucleus from Increased chromosomal deletion of gene locus in metastatic tumors (mDia2) Rac, RhoB, endosomes erythroblast, endosome motility, microtubule DIP* stabilization FMNL1 (FRLα) Cdc42 Cell cortex, Phagocytosis, T cell polarity Overexpression is linked to leukemia and non-Hodgkin lymphoma microtubule- organizing center FMNL2/FRL3/ RhoC ND Cell motility Upregulated in metastatic colorectal cancer, chromosomal deletion is FHOD2 associated with mental retardation FMNL3/FRL2 Constituently Stress fi bers ND ND active DAAM1 Dishevelled Cell cortex Planar cell polarity ND DAAM2 ND ND ND Overexpressed in schizophrenia patients Human (Mouse) FHOD1 ROCK Stress fi bers Cell motility FHOD3 ND Nestin, sarcomere Organizing sarcomeres in striated muscle cells Single-nucleotide polymorphisms associated with type 1 diabetes -

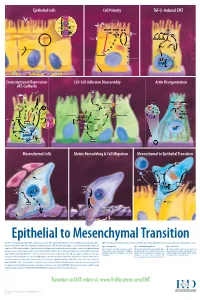

Epithelial to Mesenchymal Transition

Epithelial Cells Cell Polarity TGF-b-Induced EMT MUC-1 O-glycosylation Epithelial Cells ZO-1 Occludin Apical Membrane Tight F-Actin Microvilli Junction Claudin F-Actin p120 β-Catenin Adherens F-Actin Ezrin TGF-β dimer Junction E-Cadherin α-Catenin Plakophilin Crumbs Complex PAR Complex Desmocollin Desmoplakin Desmosome PtdIns(4,5)P2 TGF-β RII TGF-β RI CRB Cdc42Par6 Desmoglein Cytokeratin Pals1 PatJ Tight Junction Plakoglobin aPKC Par3 Domain Smad7 Extracellular PTEN JNK ERK1/2 p38 SARA Smurf1 Cortical Actin Cytoskeleton Space Par3 ZO-1 Adherens Junction PI 3-K Domain Smad-independent Signaling (–) Smad7 Translocation Smad2/3 PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 Smad4 Smad4 NEDD4 Cytokeratin Intermediate Filaments Smad2 Smad4 Smad3 LLGL Proteasome SCRIB DLG Scribble Complex Fibronectin Twist Smad2/3 Vitronectin ZEB 1/2 Microtubule Network Smad4 N-Cadherin Snail Basolateral Membrane CoA, Collagen I Slug CoR MMPs DNA-binding (+) Claudin Desmoplakin Transcription Factor Occludin Cytokeratins E-Cadherin Plakoglobin Integrins β α Nidogen-1/Entactin Perlecan Laminin Collagen IV Transcriptional Repression Cell-Cell Adhesion Disassembly Actin Reorganization of E-Cadherin TGF-β dimer EGF TGF-β RII TGF-β RI IGF FGF Receptor TNF-α Tyrosine Kinase Par6 TNF RI Apical Focal Adhesion Constriction Actin Depolymerization F-Actin Smurf1 Occludin Wnt Frizzled Myosin II Ras RhoA α-Actinin Myosin II ROCK AxinCK1 Dishevelled GSK-3 PI 3-K Src Zyxin MLC Phosphatase APC Proteasome FAK Vinculin RhoA ILK Talin (Inactive) Hakai Talin FAK F-Actin E-Cadherin LIMK Akt Paxillin FAK Stress -

Reactive Stroma in Human Prostate Cancer: Induction of Myofibroblast Phenotype and Extracellular Matrix Remodeling1

2912 Vol. 8, 2912–2923, September 2002 Clinical Cancer Research Reactive Stroma in Human Prostate Cancer: Induction of Myofibroblast Phenotype and Extracellular Matrix Remodeling1 Jennifer A. Tuxhorn, Gustavo E. Ayala, Conclusions: The stromal microenvironment in human Megan J. Smith, Vincent C. Smith, prostate cancer is altered compared with normal stroma and Truong D. Dang, and David R. Rowley2 exhibits features of a wound repair stroma. Reactive stroma is composed of myofibroblasts and fibroblasts stimulated to Departments of Molecular and Cellular Biology [J. A. T., T. D. D., express extracellular matrix components. Reactive stroma D. R. R.] and Pathology [G. E. A., M. J. S., V. C. S.] Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas 77030 appears to be initiated during PIN and evolve with cancer progression to effectively displace the normal fibromuscular stroma. These studies and others suggest that TGF-1isa ABSTRACT candidate regulator of reactive stroma during prostate can- Purpose: Generation of a reactive stroma environment cer progression. occurs in many human cancers and is likely to promote tumorigenesis. However, reactive stroma in human prostate INTRODUCTION cancer has not been defined. We examined stromal cell Activation of the host stromal microenvironment is pre- phenotype and expression of extracellular matrix compo- dicted to be a critical step in adenocarcinoma growth and nents in an effort to define the reactive stroma environ- progression (1–5). Several human cancers have been shown to ment and to determine its ontogeny during prostate cancer induce a stromal reaction or desmoplasia as a component of progression. carcinoma progression. However, the specific mechanisms of Experimental Design: Normal prostate, prostatic intra- stromal cell activation are not known, and the extent to which epithelial neoplasia (PIN), and prostate cancer were exam- stroma regulates the biology of tumorigenesis is not fully un- ined by immunohistochemistry. -

Stress Fibers Are Generated by Two Distinct Actin Assembly Mechanisms

Published May 1, 2006 JCB: ARTICLE Stress fi bers are generated by two distinct actin assembly mechanisms in motile cells Pirta Hotulainen and Pekka Lappalainen Institute of Biotechnology, University of Helsinki, Helsinki FI-00014, Finland tress fi bers play a central role in adhesion, motility, ing of myosin bundles and Arp2/3-nucleated actin and morphogenesis of eukaryotic cells, but the bundles at the lamella. Remarkably, dorsal stress fi bers S mechanism of how these and other contractile and transverse arcs can be converted to ventral stress actomyosin structures are generated is not known. By fi bers anchored to focal adhesions at both ends. Fluo- analyzing stress fi ber assembly pathways using live cell rescence recovery after photobleaching analysis re- microscopy, we revealed that these structures are gener- vealed that actin fi lament cross-linking in stress fi bers is ated by two distinct mechanisms. Dorsal stress fi bers, highly dynamic, suggesting that the rapid association– which are connected to the substrate via a focal adhe- dissociation kinetics of cross-linkers may be essential sion at one end, are assembled through formin (mDia1/ for the formation and contractility of stress fi bers. Based Downloaded from DRF1)–driven actin polymerization at focal adhesions. on these data, we propose a general model for as- In contrast, transverse arcs, which are not directly an- sembly and maintenance of contractile actin structures chored to substrate, are generated by endwise anneal- in cells. Introduction on April 3, 2017 Cell locomotion and adhesion play key roles during embryonic concentrate polymerization to the protruding region close to development, tissue regeneration, immune responses, and the plasma membrane (for reviews see Pantaloni et al., 2001; wound healing in multicellular organisms. -

Expression of Smooth Muscle and Extracellular Matrix Proteins in Relation to Airway Function in Asthma

Expression of smooth muscle and extracellular matrix proteins in relation to airway function in asthma Annelies M. Slats, MD,a Kirsten Janssen, BHe,a Annemarie van Schadewijk, MSc,a Dirk T. van der Plas, BSc,a Robert Schot, BSc,a Joost G. van den Aardweg, MD, PhD,b Johan C. de Jongste, MD, PhD,c Pieter S. Hiemstra, PhD,a Thais Mauad, MD,d Klaus F. Rabe, MD, PhD,a and Peter J. Sterk, MD, PhDa,e Leiden, Alkmaar, Rotterdam, and Amsterdam, The Netherlands, and Sa˜o Paulo, Brazil Background: Smooth muscle content is increased within the selective expression of airway smooth muscle proteins and airway wall in patients with asthma and is likely to play a role in components of the extracellular matrix. (J Allergy Clin airway hyperresponsiveness. However, smooth muscle cells Immunol 2008;121:1196-202.) express several contractile and structural proteins, and each of these proteins may influence airway function distinctly. Key words: Actin, desmin, elastin, airway smooth muscle, extracel- Objective: We examined the expression of contractile and lular matrix, lung function, hyperresponsiveness, deep inspiration- structural proteins of smooth muscle cells, as well as induced bronchodilation, bronchial biopsies extracellular matrix proteins, in bronchial biopsies of patients with asthma, and related these to lung function, airway hyperresponsiveness, and responses to deep inspiration. Asthma is characterized by chronic airway inflammation, Methods: Thirteen patients with asthma (mild persistent, which is presumed to contribute to variable airways obstruction 1 atopic, nonsmoking) participated in this cross-sectional study. and bronchial hyperresponsiveness. However, recent studies FEV1% predicted, PC20 methacholine, and resistance of the have led to a reappraisal of the role of airway smooth muscle in 2 respiratory system by the forced oscillation technique during asthma pathophysiology. -

A Computational Study of Stress Fiber-Focal Adhesion Dynamics

A computational study of stress fiber-focal adhesion dynamics governing cell contractility M. Maraldi1, C. Valero2, K. Garikipati1;3∗ 1Department of Mechanical Engineering, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan 2M2BE, Aragon´ Institute of Engineering Research (I3A), University of Zaragoza, Zaragoza, Spain 3Department of Mathematics, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan Abstract We apply a recently developed model of cytoskeletal force generation to study a cell’s intrinsic contractility, as well as its response to external loading. The model is based on a non-equilibrium thermodynamic treatment of the mechano-chemistry governing force in the stress fiber-focal adhesion system. Our computational study suggests that the mechan- ical coupling between the stress fibers and focal adhesions leads to a complex, dynamic, mechano-chemical response. We collect the results in response maps whose regimes are distinguished by the initial geometry of the stress fiber-focal adhesion system, and by the external load on the cell. The results from our model connect qualitatively with recent stud- ies on the force response of smooth muscle cells on arrays of polymeric microposts (Mann et al., Lab. on a Chip, 12, 731-740, 2012). INTRODUCTION In contractile cells, such as smooth muscle cells and fibroblasts, the generation of traction force is the result of two different actions: myosin-powered cytoskeletal contractility and external mechanical stimuli (applied stretch or force). The cooperation between these two aspects de- termines the level of the force within the cell and influences the development of cytoskeletal components via the (un)binding of proteins. Important cytoskeletal components that mediate this interplay of mechanics and chemistry are stress fibers and focal adhesions. -

Skeletal Reorganization and Chromatin Accessibility During Re- Vascularization-Based Blastema Regeneration

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 23 April 2021 doi:10.20944/preprints202104.0642.v1 Article Keratin5-BMP4 mechanosignaling network regulates cell cyto- skeletal reorganization and chromatin accessibility during re- vascularization-based blastema regeneration Xuelong Wang 1,2,4,†, Huiping Guo 1,6,†, Feifei Yu 1,†, Hui Zhang 1, Ying Peng 1, Chenghui Wang 3, Gang Wei 2, Jizhou Yan 1,5,* 1 Department of Developmental Biology, Institute for Marine Biosystem and Neurosciences, Shanghai Ocean University, Shanghai, China. 2 CAS Key Laboratory of Computational Biology, Shanghai Institute of Nutrition and Health, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Shanghai, China 3 Department of Aquaculture, Shanghai Ocean University, Shanghai, China. 4 Present address: Pancreatic Disease Center, Ruijin Hospital, School of Medicine, Shanghai Jiao Tong Univer- sity, Shanghai, China. 5 CellGene Bioscience, Shanghai, China. * Correspondence: [email protected] † These authors contributed equally to this study. Abstract: Heart regeneration after myocardial infarction remains challenging in reconstruction of blood resupply system. Here, we find that in zebrafish heart after resection of the ventricular apex, the local myocardial cells and the clotted blood cells undergo cell remodeling process via cytoplas- mic exocytosis and nuclear reorganization within revascularization-based blastema. The regenera- tive processes are visualized by spatiotemporal expression of three blastema representative factors (alpha-SMA- which marks for fibrogenesis, Flk1for angiogenesis/hematopoiesis, and Pax3a for re- musculogensis),and two histone modifications (H3K9Ac and H3K9Me3 mark for chromatin re- modeling). Using the cultured zebrafish embryonic fibroblasts we identify blastema fraction com- ponents and show that Krt5 peptide could link cytoskeleton network and BMP4 signaling pathway to regulate the transcription and chromatin accessibility at the blastema representative genes and bmp4 genes. -

Evidence for the Nonmuscle Nature of The" Myofibroblast" of Granulation Tissue and Hypertropic Scar. an Immunofluorescence Study

American Journal of Pathology, Vol. 130, No. 2, February 1988 Copyright i American Association of Pathologists Evidencefor the Nonmuscle Nature ofthe "Myofibroblast" ofGranulation Tissue and Hypertropic Scar An Immunofluorescence Study ROBERT J. EDDY, BSc, JANE A. PETRO, MD, From the Department ofAnatomy, the Department ofSurgery, and JAMES J. TOMASEK, PhD Division ofPlastic and Reconstructive Surgery, and the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, New York Medical College, Valhalla, New York Contraction is an important phenomenon in wound cell-matrix attachment in smooth muscle and non- repair and hypertrophic scarring. Studies indicate that muscle cells, respectively. Myofibroblasts can be iden- wound contraction involves a specialized cell known as tified by their intense staining of actin bundles with the myofibroblast, which has morphologic character- either anti-actin antibody or NBD-phallacidin. Myofi- istics of both smooth muscle and fibroblastic cells. In broblasts in all tissues stained for nonmuscle but not order to better characterize the myofibroblast, the au- smooth muscle myosin. In addition, nonmuscle myo- thors have examined its cytoskeleton and surrounding sin was localized as intracellular fibrils, which suggests extracellular matrix (ECM) in human burn granula- their similarity to stress fibers in cultured fibroblasts. tion tissue, human hypertrophic scar, and rat granula- The ECM around myofibroblasts stains intensely for tion tissue by indirect immunofluorescence. Primary fibronectin but lacks laminin, which suggests that a antibodies used in this study were directed against 1) true basal lamina is not present. The immunocytoche- smooth muscle myosin and 2) nonmuscle myosin, mical findings suggest that the myofibroblast is a spe- components ofthe cytoskeleton in smooth muscle and cialized nonmuscle type of cell, not a smooth muscle nonmuscle cells, respectively, and 3) laminin and 4) cell. -

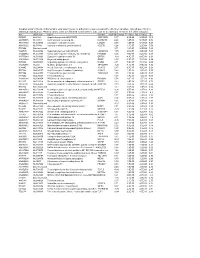

Supplementary File 2A Revised

Supplementary file 2A. Differentially expressed genes in aldosteronomas compared to all other samples, ranked according to statistical significance. Missing values were not allowed in aldosteronomas, but to a maximum of five in the other samples. Acc UGCluster Name Symbol log Fold Change P - Value Adj. P-Value B R99527 Hs.8162 Hypothetical protein MGC39372 MGC39372 2,17 6,3E-09 5,1E-05 10,2 AA398335 Hs.10414 Kelch domain containing 8A KLHDC8A 2,26 1,2E-08 5,1E-05 9,56 AA441933 Hs.519075 Leiomodin 1 (smooth muscle) LMOD1 2,33 1,3E-08 5,1E-05 9,54 AA630120 Hs.78781 Vascular endothelial growth factor B VEGFB 1,24 1,1E-07 2,9E-04 7,59 R07846 Data not found 3,71 1,2E-07 2,9E-04 7,49 W92795 Hs.434386 Hypothetical protein LOC201229 LOC201229 1,55 2,0E-07 4,0E-04 7,03 AA454564 Hs.323396 Family with sequence similarity 54, member B FAM54B 1,25 3,0E-07 5,2E-04 6,65 AA775249 Hs.513633 G protein-coupled receptor 56 GPR56 -1,63 4,3E-07 6,4E-04 6,33 AA012822 Hs.713814 Oxysterol bining protein OSBP 1,35 5,3E-07 7,1E-04 6,14 R45592 Hs.655271 Regulating synaptic membrane exocytosis 2 RIMS2 2,51 5,9E-07 7,1E-04 6,04 AA282936 Hs.240 M-phase phosphoprotein 1 MPHOSPH -1,40 8,1E-07 8,9E-04 5,74 N34945 Hs.234898 Acetyl-Coenzyme A carboxylase beta ACACB 0,87 9,7E-07 9,8E-04 5,58 R07322 Hs.464137 Acyl-Coenzyme A oxidase 1, palmitoyl ACOX1 0,82 1,3E-06 1,2E-03 5,35 R77144 Hs.488835 Transmembrane protein 120A TMEM120A 1,55 1,7E-06 1,4E-03 5,07 H68542 Hs.420009 Transcribed locus 1,07 1,7E-06 1,4E-03 5,06 AA410184 Hs.696454 PBX/knotted 1 homeobox 2 PKNOX2 1,78 2,0E-06 -

Endothelial Cadherin Endothelium Is Regulated by Vascular Progenitor

Migration of Human Hematopoietic Progenitor Cells Across Bone Marrow Endothelium Is Regulated by Vascular Endothelial Cadherin This information is current as of October 1, 2021. Jaap D. van Buul, Carlijn Voermans, Veronique van den Berg, Eloise C. Anthony, Frederik P. J. Mul, Sandra van Wetering, C. Ellen van der Schoot and Peter L. Hordijk J Immunol 2002; 168:588-596; ; doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.2.588 http://www.jimmunol.org/content/168/2/588 Downloaded from References This article cites 54 articles, 33 of which you can access for free at: http://www.jimmunol.org/content/168/2/588.full#ref-list-1 http://www.jimmunol.org/ Why The JI? Submit online. • Rapid Reviews! 30 days* from submission to initial decision • No Triage! Every submission reviewed by practicing scientists • Fast Publication! 4 weeks from acceptance to publication by guest on October 1, 2021 *average Subscription Information about subscribing to The Journal of Immunology is online at: http://jimmunol.org/subscription Permissions Submit copyright permission requests at: http://www.aai.org/About/Publications/JI/copyright.html Email Alerts Receive free email-alerts when new articles cite this article. Sign up at: http://jimmunol.org/alerts The Journal of Immunology is published twice each month by The American Association of Immunologists, Inc., 1451 Rockville Pike, Suite 650, Rockville, MD 20852 Copyright © 2002 by The American Association of Immunologists All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0022-1767 Online ISSN: 1550-6606. Migration of Human Hematopoietic Progenitor Cells Across Bone Marrow Endothelium Is Regulated by Vascular Endothelial Cadherin1 Jaap D. van Buul,* Carlijn Voermans,* Veronique van den Berg,* Eloise C. -

Profilin and Formin Constitute a Pacemaker System for Robust Actin

RESEARCH ARTICLE Profilin and formin constitute a pacemaker system for robust actin filament growth Johanna Funk1, Felipe Merino2, Larisa Venkova3, Lina Heydenreich4, Jan Kierfeld4, Pablo Vargas3, Stefan Raunser2, Matthieu Piel3, Peter Bieling1* 1Department of Systemic Cell Biology, Max Planck Institute of Molecular Physiology, Dortmund, Germany; 2Department of Structural Biochemistry, Max Planck Institute of Molecular Physiology, Dortmund, Germany; 3Institut Curie UMR144 CNRS, Paris, France; 4Physics Department, TU Dortmund University, Dortmund, Germany Abstract The actin cytoskeleton drives many essential biological processes, from cell morphogenesis to motility. Assembly of functional actin networks requires control over the speed at which actin filaments grow. How this can be achieved at the high and variable levels of soluble actin subunits found in cells is unclear. Here we reconstitute assembly of mammalian, non-muscle actin filaments from physiological concentrations of profilin-actin. We discover that under these conditions, filament growth is limited by profilin dissociating from the filament end and the speed of elongation becomes insensitive to the concentration of soluble subunits. Profilin release can be directly promoted by formin actin polymerases even at saturating profilin-actin concentrations. We demonstrate that mammalian cells indeed operate at the limit to actin filament growth imposed by profilin and formins. Our results reveal how synergy between profilin and formins generates robust filament growth rates that are resilient to changes in the soluble subunit concentration. DOI: https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.50963.001 *For correspondence: peter.bieling@mpi-dortmund. mpg.de Introduction Competing interests: The Eukaryotic cells move, change their shape and organize their interior through dynamic actin net- authors declare that no works. -

Phospholipids Regulate Localization and Activity of Mdia1 Formin

AAM (author's accepted manuscript) Eur. J. Cell Biol. 89:723-732, 2010 Phospholipids regulate localization and activity of mDia1 formin Nagendran Ramalingam1,2,*, Hongxia Zhao3, Dennis Breitsprecher4, Pekka Lappalainen3, Jan Faix4 and Michael Schleicher1§ 1Institute for Anatomy and Cell Biology, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universitaet, 80336 Muenchen, Germany, 2Center for Biochemistry I, Center for Molecular Medicine Cologne (CMMC) and Cologne Excellence Cluster on Cellular Stress Responses and Aging-Associated Diseases (CECAD), Universitaet zu Koeln, 50931 Koeln, Germany, 3Institute of Biotechnology, PO Box 56, 00014 University of Helsinki, Finland, 4Institute for Biophysical Chemistry, Hannover Medical School, 30623 Hannover, Germany Running title: Phospholipids regulate mDia1 * Current address: Department of Pathology and Cell Biology, Columbia University, New York, NY 10032, USA § Corresponding author: Prof. Dr. Michael Schleicher Institute for Anatomy and Cell Biology LMU Muenchen Schillerstr.42, 80336 Muenchen, Germany, Telephone: +49-89-2180-75876, Fax: +49-89-2180-75004, E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT Diaphanous-related formins (DRFs) are large multi-domain proteins that nucleate and assemble linear actin filaments. Binding of active Rho family proteins to the GTPase-binding domain (GBD) triggers localization at the membrane and the activation of most formins if not all. In recent years GTPase regulation of formins has been extensively studied, but other molecular mechanisms that determine subcellular distribution or regulate formin activity have remained poorly understood. Here, we provide evidence that the activity and localization of mouse formin mDia1 can be regulated through interactions with phospholipids. The phospholipid-binding sites of mDia1 are clusters of positively charged residues in the N-terminal basic domain (BD) and at the C-terminal region.