Armenian Cuisine: a Construct in the Service of Identity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Menu-Glendale-Dine-In--Dinner.Pdf

SCENES OF LEBANON 304 North Brand Boulevard Glendale, California 91203 818.246.7775 (phone) 818.246.6627 (fax) www.carouselrestaurant.com City of Lebanon Carousel Restaurant is designed with the intent to recreate the dining and entertainment atmosphere of the Middle East with its extensive variety of appetizers, authentic kebabs and specialties. You will be enticed with our Authentic Middle Eastern delicious blend of flavors and spices specific to the Cuisine Middle East. We cater to the pickiest of palates and provide vegetarian menus as well to make all our guests feel welcome. In the evenings, you will be enchanted Live Band with our award-winning entertainment of both singers and and Dance Show Friday & Saturday specialty dancers. Please join us for your business Evenings luncheons, family occasions or just an evening out. 9:30 pm - 1:30 am We hope you enjoy your experience here. TAKE-OUT & CATERING AVAILABLE 1 C A R O U sel S P ec I al TY M E Z as APPETIZERS Mantee (Shish Barak) Mini meat pies, oven baked and topped with a tomato yogurt sauce. 12 VG Vegan Mantee Mushrooms, spinach, quinoa topped with vegan tomato sauce & cashew milk yogurt. 13 Frri (Quail) Pan-fried quail sautéed with sumac pepper and citrus sauce. 15 Frog Legs Provençal Pan-fried frog legs with lemon juice, garlic and cilantro. 15 Filet Mignon Sautée Filet mignon diced, sautéed with onions in tomato & pepper paste. 15 Hammos Filet Sautée Hammos topped with our sautéed filet mignon. 14 Shrimp Kebab Marinated with lemon juice, garlic, cilantro and spices. -

Tourism Development Trends in Armenia

Tourism Education Studies and Practice, 2018, 5(1) Copyright © 2018 by Academic Publishing House Researcher s.r.o. Published in the Slovak Republic Tourism Education Studies and Practice Has been issued since 2014. E-ISSN: 2409-2436 2018, 5(1): 20-25 DOI: 10.13187/tesp.2018.1.20 www.ejournal10.com Tourism Development Trends in Armenia Gayane Tovmasyan а , * Rubik Tovmasyan b a ''AMBERD'' Research Center of the Armenian State University of Economics, Armenia b Public Administration Academy of the Republic of Armenia, Armenia Abstract In recent years tourism develops rapidly in Armenia. The main tourism statistics, tourism competitiveness index are presented and analyzed in the article. The article discusses the main types of tourism that may be developed in Armenia such as religious, historical-cultural, spa-resort, eco- and agri-, sport and adventure, gastronomic, urban, educational, scientific, medical tourism. Although the growth of tourism in recent years, there are still many problems that hinder the promotion of tourism. The tourism statistics, marketing policy, legislation must be improved. Besides, the educational system must meet the requirements of the labor market. Tourist specialists must have all the skills for tourism industry development. Thus, the main problems are revealed and the trends and ways of tourism development are analyzed in the article. Keywords: tourism, competitiveness, types of tourism, marketing, statistics, GDP, tourism development trends. 1. Introduction Tourism is one of the largest industries all over the world and develops very fast. Year by year more and more people travel to visit friends and relatives, to have leisure time, or with the purpose of business travel, education, health recovery, etc. -

Selected Works of Chokan Valikhanov Selected Works of Chokan Valikhanov

SELECTED WORKS OF CHOKAN VALIKHANOV CHOKAN OF WORKS SELECTED SELECTED WORKS OF CHOKAN VALIKHANOV Pioneering Ethnographer and Historian of the Great Steppe When Chokan Valikhanov died of tuberculosis in 1865, aged only 29, the Russian academician Nikolai Veselovsky described his short life as ‘a meteor flashing across the field of oriental studies’. Set against his remarkable output of official reports, articles and research into the history, culture and ethnology of Central Asia, and more important, his Kazakh people, it remains an entirely appropriate accolade. Born in 1835 into a wealthy and powerful Kazakh clan, he was one of the first ‘people of the steppe’ to receive a Russian education and military training. Soon after graduating from Siberian Cadet Corps at Omsk, he was taking part in reconnaissance missions deep into regions of Central Asia that had seldom been visited by outsiders. His famous mission to Kashgar in Chinese Turkestan, which began in June 1858 and lasted for more than a year, saw him in disguise as a Tashkent mer- chant, risking his life to gather vital information not just on current events, but also on the ethnic make-up, geography, flora and fauna of this unknown region. Journeys to Kuldzha, to Issyk-Kol and to other remote and unmapped places quickly established his reputation, even though he al- ways remained inorodets – an outsider to the Russian establishment. Nonetheless, he was elected to membership of the Imperial Russian Geographical Society and spent time in St Petersburg, where he was given a private audience by the Tsar. Wherever he went he made his mark, striking up strong and lasting friendships with the likes of the great Russian explorer and geographer Pyotr Petrovich Semyonov-Tian-Shansky and the writer Fyodor Dostoyevsky. -

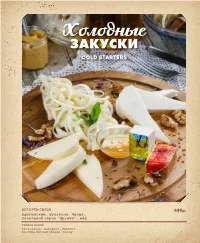

Закуски Cold Starters

Холодные ЗАКУСКИ COLD STARTERS АССОРТИ СЫРОВ 440р. Адыгейский, Сулугуни, Чечил, плавленый сырок “Дружба”, мёд CHEESE PLATE Circassian, Suluguni, Chechil, Druzhba melted cheese, honey ЯЙЦО ПОД МАЙОНЕЗОМ 90р. ФОРШМАК ИЗ СЕЛЬДИ, 190р . С ЗЕЛЁНЫМ ГОРОШКОМ ПОДАЁТСЯ С РЖАНЫМИ ТОСТАМИ EGG WITH MAYO AND GREEN PEAS HERRING VORSCHMACK, SERVED WITH TOASTED RYE BREAD ДОМАШНИЕ СОЛЕНЬЯ 290р. огурцы соленые, капуста квашеная, капуста по-грузински, помидоры малосольные, чеснок маринованный HOMEMADE PICKLES pickles, sauerkraut, Georgian cabbage, mild-cured tomatoes, brined garlic Сало домашнее * Взять 1 кг cала, нашпиговать 2-3 головками чеснока. Смешать специи: красный молотый перец, тмин, чеснок, молотую паприку, лавровый лист, каменную соль и 15 горошин чёрного перца. Тщательно натереть сало смесью специй, завернуть в марлю и оставить в холодном месте ДОМАШНЕЕ САЛО: СОЛЁНОЕ, на неделю. КОПЧЁНОЕ И С КРАСНЫМ ПЕРЦЕМ 290р. HOMEMADE SALO PLATE: PICKLED, SMOKED, RUBBED WITH RED PEPPER СЕЛЬДЬ АТЛАНТИЧЕСКАЯ С ОТВАРНЫМ КАРТОФЕЛЕМ 290р. ATLANTIC HERRING СОЛЕНЫЕ ГРУЗДИ С ПОДСОЛНЕЧНЫМ WITH BOILED POTATOES МАСЛОМ И СМЕТАНОЙ 320р. PICKLED MUSHROOMS WITH SUNFLOWER OIL AND SOUR CREAM * ДАННЫЙ РЕЦЕПТ ПРЕДСТАВЛЕН ДЛЯ ПРИГОТОВЛЕНИЯ В ДОМАШНИХ УСЛОВИЯХ МЯСНОЕ АССОРТИ 450р. ЛОСОСЬ СЛАБОЙ СОЛИ 470р. колбаса сырокопчёная, копчёная куриная грудка, буженина MILD-CURED SALMON MEAT PLATE raw smoked sausage, smoked chicken breast, pork roast РЫБНОЕ АССОРТИ 490р. скумбрия пряного посола, масляная рыба, лосось слабой соли FISH PLATE spiced-salted mackerel, dollar fish, mild-cured salmon Салаты SALADS ВИНЕГРЕТ С БАЛТИЙСКОЙ КИЛЬКОЙ 190р . VINEGRET WITH BALTIC SPRAT ПОЖАЛУЙСТА, СООБЩИТЕ ОФИЦИАНТУ, ЕСЛИ У ВАС ЕСТЬ АЛЛЕРГИЯ НА КАКИЕ-ЛИБО ПРОДУКТЫ. PLEASE, INFORM YOUR WAITER IF YOU ARE ALLERGIC TO CERTAIN INGREDIENTS. Домашний "Провансаль"* 250 мл раст. масла 2 желтка 0,5-1 ст. -

The Cost of Memorializing: Analyzing Armenian Genocide Memorials and Commemorations in the Republic of Armenia and in the Diaspora

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL FOR HISTORY, CULTURE AND MODERNITY www.history-culture-modernity.org Published by: Uopen Journals Copyright: © The Author(s). Content is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence eISSN: 2213-0624 The Cost of Memorializing: Analyzing Armenian Genocide Memorials and Commemorations in the Republic of Armenia and in the Diaspora Sabrina Papazian HCM 7: 55–86 DOI: 10.18352/hcm.534 Abstract In April of 1965 thousands of Armenians gathered in Yerevan and Los Angeles, demanding global recognition of and remembrance for the Armenian Genocide after fifty years of silence. Since then, over 200 memorials have been built around the world commemorating the vic- tims of the Genocide and have been the centre of hundreds of marches, vigils and commemorative events. This article analyzes the visual forms and semiotic natures of three Armenian Genocide memorials in Armenia, France and the United States and the commemoration prac- tices that surround them to compare and contrast how the Genocide is being memorialized in different Armenian communities. In doing so, this article questions the long-term effects commemorations have on an overall transnational Armenian community. Ultimately, it appears that calls for Armenian Genocide recognition unwittingly categorize the global Armenian community as eternal victims, impeding the develop- ment of both the Republic of Armenia and the Armenian diaspora. Keywords: Armenian Genocide, commemoration, cultural heritage, diaspora, identity, memorials HCM 2019, VOL. 7 Downloaded from Brill.com10/05/202155 12:33:22PM via free access PAPAZIAN Introduction On 24 April 2015, the hundredth anniversary of the commencement of the Armenian Genocide, Armenians around the world collectively mourned for and remembered their ancestors who had lost their lives in the massacres and deportations of 1915.1 These commemorations took place in many forms, including marches, candlelight vigils, ceremo- nial speeches and cultural performances. -

Ethnic Return of Armenian Americans: Per- Spectives

Karolina Pawłowska: Ethnic return of Armenian Americans: Perspectives Ethnic return of Armenian Americans: Per- spectives Karolina Pawłowska University of Adam Mickiewicz in Poznan, [email protected] Abstract The field research conducted among the very few Armenian Americans who have moved to Armenia showed that the phenomena of migration of the diaspora of Armenians to Armenia holds great potential both as a theoretical issue within migration studies and potentially a social phenomenon, as Armenian Americans differ from other migrants and expats in Armenia, because they carry stereotyped pre-images of that land that influence their expectations toward their future lives there. Field research conducted in Armenia in 2012 shows that the disillusionment that repatriation brings causes internal tensions and identity crises, eventually forcing migrants to redefine their role in Armenia in the frame- work of their contribution to the development of their homeland, often isolating them from local Armenians through diaspora practices and maintaining the symbolic boundary between these two groups of Armenians in Armenia. KEYWORDS: diaspora, ethnic return, symbolic boundary, boundary maintenance, so- journers Introduction Both diaspora and specifically the Armenian diaspora are topics well explored in litera- ture (Cohen 2008; Dufoix 2008; Bauböck & Faist 2010; Tölölyan 2012). However, the migration of Armenians from the diaspora to Armenia is not a popular topic among re- searchers and the diaspora of Armenians themselves. The number -

Turkish Delights: Stunning Regional Recipes from the Bosphorus to the Black Sea Pdf

FREE TURKISH DELIGHTS: STUNNING REGIONAL RECIPES FROM THE BOSPHORUS TO THE BLACK SEA PDF John Gregory-Smith | 240 pages | 12 Oct 2015 | Kyle Books | 9780857832986 | English | London, United Kingdom Turkish Delights: Stunning Regional Recipes from the Bosphorus to the Black Sea | Eat Your Books She hopes these recipes will take you on a Turkish journey - to learn, taste and enjoy the delicious foods of her homeland and most importantly to feel the warmth and sharing spirit of Turkish culture. Turkish cuisine is based on seasonal fresh produce. It is healthy, delicious, affordable and easy to make. She shows you how to recreate these wonderful recipes in your own home, wherever you are in the world. Her dishes are flavoured naturally with: olive oil, lemon juice, nuts, spices, as well as condiments like pomegranate molasses and nar eksisi. Turkish cuisine also offers plenty of options for vegetarian, gluten-free and vegan diets. She hopes her recipes inspire you to recreate them in your own kitchen and that they can bring you fond memories of your time in Turkey or any special moments shared with loved ones. Her roots - Ancient Antioch, Antakya Her family's roots date back to ancient Antioch, Antakya, located in the southern part of Turkey, near the Syrian border. This book is a special tribute to Antakya and southern Turkish cuisine, as her cooking has been inspired by this special land. Her parents, Orhan and Gulcin, were both born in Antakya and she spent many happy childhood holidays in this ancient city, playing in the courtyard of her grandmother's year old stone home, under the fig and walnut trees. -

Cold Appetizers

COLD APPETIZERS SHEKI SYUZME 19 HOMEMADE PICKLES 33 Traditional milk product Assorted fruit and vegetable pickles from Gabala KUKU 44 BOUQUET 45 Traditional baked omelette with Fresh greens with tomatoes, cucumbers, assorted greens and nuts green peppers, radish and onion AUBERGINE LAVANGI 39 BLACK CAVIAR 475 Grilled eggplant rolls stuffed with walnuts, onion, dressed with plum sauce AUBERGINE MEZE 32 Grilled eggplant , served with red pepper sauce LAVANGI OF CHICKEN 42 Rolls of chicken breast, stuffed with walnuts, EGGPLANT CAVIAR 28 onion, dressed with plum sauce Minced grilled eggplant, bell pepper, tomatoes, greens, onion and garlic, served with homemade dairy butter AZERBAIJANI CHEESE PLATE 49 Assorted Azerbaijani cheeses HOT APPETIZERS GYURZA 63 CHICKEN LAVANGI 84 Dough stuffed with minced Whole farm chicken stuffed with walnuts, onion lamb meat – served fried or boiled dressed with plum sauce, cooked in the oven KUTUM LAVANGI 95 AZERI STYLE SHAKSHUKA 55 Azerbaijani boneless fish stuffed with walnuts, Traditional cooked omelette with Baku tomatoes, onion, dressed with plum sauce, cooked in the oven slow-cooked BAKU GUTABS Thin dough in the shape of a crescent with a filling of: MEAT 9 CHEESE 9 GREENS 8 PUMPKIN 8 Persons suffering from food allergies and having special dietary requirements can contact the manager and get information about the ingredients of each dish. Prices in the menu shown in AED and include VAT SALADS Azerbaijani vegetables and greens are famous for their bright taste and unique aromas KABAB SALAD 60 WARM SALAD -

Yeghishe Charents March 13, 1897 — November 29, 1937

Հ.Մ.Ը.Մ.-Ի ԳԼԵՆԴԵԼԻ ԱՐԱՐԱՏ ՄԱՍՆԱՃԻՒՂԻ ՄՇԱԿՈՒԹԱՅԻՆ ԲԱԺԱՆՄՈՒՄՔ Homenetmen Glendale Ararat Chapter Cultural Division Get to Know… Volume 2, Issue 3 March 2009 YEGHISHE CHARENTS MARCH 13, 1897 — NOVEMBER 29, 1937 Yeghishe Charents (Yeghishe Soghomonian) was born in March 13, 1897 in Kars, currently located in North-Eastern Turkey. Born into a family of tradesman, he became one of the legendary figures of Armenian art and anti-Soviet activism. His works have fostered generations of patriotic Armenians and have been translated and read by peoples as diverse as the subjects on which he wrote. One of the leaders of the literary elite of the Soviet Union, his poetic dynamism and musical modality set him apart as one of the most inspired poets—not Armenian poet, but poet—of the twentieth century. Charents spent 1924 and 1925 as a Soviet diplomat, traveling throughout the Armenian Diaspora urging Armenian writers to return to Armenia, and continue their literary work there. After returning to Armenia, in 1925, he and a group of other Armenian writers founded a literary organization called the Association of Armenian Proletarian Writers. Unfortunately, many of his colleagues were either deported to Siberia, or shot or both, under Stalin’s regime. During the years following 1925, Charents published his satirical novel, Land of Nairi (Yerkir Nairi), which rapidly became a great success among the people. Later on, Charents became the director of Armenia’s State Publishing House, while he continued his literary career, and began to translate, into Armenian, literary works by various writers. Charents also published such famous novels as: Rubayat (1927), Epic Dawn (Epikakan Lussapats, 1930), and Book of the Road (Grik Chanaparhi, 1933). -

What Makes a Restaurant Ethnic? (A Case Study Of

FORUM FOR ANTHROPOLOGY AND CULTURE, 2017, NO. 13 WHAT MAKES A RESTAURANT ETHNIC? (A CASE STUDY OF ARMENIAN RESTAURANTS IN ST PETERSBURG) Evgenia Guliaeva Th e Russian Museum of Ethnography 4/1 Inzhenernaya Str., St Petersburg, Russia [email protected] A b s t r a c t: Using restaurants in St Petersburg serving Armenian cuisine as a case study, the article studies the question of what makes an ethnic restaurant ethnic, what may be learnt about ethnicity by studying a restaurant serving a national cuisine, and to what extent the image of Armenian cuisine presented in Armenian restaurants corresponds to what Armenian informants tell us. The conclusion is that the composition of the menu in these restaurants refl ects a view of Armenian cuisine from within the ethnic group itself. The representation of ethnicity is achieved primarily by discursive means. Neither owners, nor staff, nor customers from the relevant ethnic group, nor the style of the interior or music are necessary conditions for a restaurant to be accepted as ethnic. However, their presence is taken into account when the authenticity or inauthenticity of the restaurant is evaluated. Armenian informants, though, do not raise the question of authenticity: this category is irrelevant for them. Keywords: Armenians, ethnicity, ethnic restaurants, national cuisine, authenticity, St Petersburg. To cite: Guliaeva E., ‘What Makes a Restaurant Ethnic? (A Case Study of Armenian Restaurants in St Petersburg)’, Forum for Anthropology and Culture, 2017, no. 13, pp. 280–305. U R L: http://anthropologie.kunstkamera.ru/fi -

Fish Inspection Regulations Règlement Sur L'inspection Du Poisson

CANADA CONSOLIDATION CODIFICATION Fish Inspection Règlement sur Regulations l’inspection du poisson C.R.C., c. 802 C.R.C., ch. 802 Current to December 14, 2010 À jour au 14 décembre 2010 Published by the Minister of Justice at the following address: Publié par le ministre de la Justice à l’adresse suivante : http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca http://lois-laws.justice.gc.ca OFFICIAL STATUS CARACTÈRE OFFICIEL OF CONSOLIDATIONS DES CODIFICATIONS Subsections 31(1) and (3) of the Legislation Les paragraphes 31(1) et (3) de la Loi sur la Revision and Consolidation Act, in force on révision et la codification des textes législatifs, June 1, 2009, provide as follows: en vigueur le 1er juin 2009, prévoient ce qui suit : Published 31. (1) Every copy of a consolidated statute or 31. (1) Tout exemplaire d'une loi codifiée ou Codifications consolidation is consolidated regulation published by the Minister d'un règlement codifié, publié par le ministre en ver- comme élément evidence under this Act in either print or electronic form is ev- tu de la présente loi sur support papier ou sur support de preuve idence of that statute or regulation and of its contents électronique, fait foi de cette loi ou de ce règlement and every copy purporting to be published by the et de son contenu. Tout exemplaire donné comme Minister is deemed to be so published, unless the publié par le ministre est réputé avoir été ainsi pu- contrary is shown. blié, sauf preuve contraire. ... [...] Inconsistencies (3) In the event of an inconsistency between a (3) Les dispositions du -

A History of Armenian Immigration to Southern California Daniel Fittante

But Why Glendale? But Why Glendale? A History of Armenian Immigration to Southern California Daniel Fittante Abstract: Despite its many contributions to Los Angeles, the internally complex community of Armenian Angelenos remains enigmatically absent from academic print. As a result, its history remains untold. While Armenians live throughout Southern California, the greatest concentration exists in Glendale, where Armenians make up a demographic majority (approximately 40 percent of the population) and have done much to reconfigure this homogenous, sleepy, sundown town of the 1950s into an ethnically diverse and economically booming urban center. This article presents a brief history of Armenian immigration to Southern California and attempts to explain why Glendale has become the world’s most demographically concentrated Armenian diasporic hub. It does so by situating the history of Glendale’s Armenian community in a complex matrix of international, national, and local events. Keywords: California history, Glendale, Armenian diaspora, immigration, U.S. ethnic history Introduction Los Angeles contains the most visible Armenian diaspora worldwide; however yet it has received virtually no scholarly attention. The following pages begin to shed light on this community by providing a prefatory account of Armenians’ historical immigration to and settlement of Southern California. The following begins with a short history of Armenian migration to the United States. The article then hones in on Los Angeles, where the densest concentration of Armenians in the United States resides; within the greater Los Angeles area, Armenians make up an ethnic majority in Glendale. To date, the reasons for Armenians’ sudden and accelerated settlement of Glendale remains unclear. While many Angelenos and Armenian diasporans recognize Glendale as the epicenter of Armenian American habitation, no one has yet clarified why or how this came about.