8]<OU 1 60471 >

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Global Transmission Weekly Update on the Global Electricity Transmission Industry

September 03, 2012 Global Transmission Weekly Update on the global electricity transmission industry INSIDE THIS ISSUE NORTH AMERICA 2 PJM cancels PATH and MAPP projects 2 Rock Island Clean Line project faces opposition in Illinois 2 Opposition against Champlain-Hudson Power Express transmission line growing 2 Clean Line hosts public meetings for Grain Belt Express line 3 Entergy Arkansas files testimony with state PSC 3 Entergy proposal of shifting ICT services to MISO attracts strong opposition 3 MISO approves scaled down version of Bay Lake Project 3 Enbridge repays USD151 million federal loan 4 I-5 Corridor to cost USD12 million to tax payers 4 NWE and BPA announce transmission upgrades in Montana 4 CWL proposes third route option for Mill Creek substation transmission lines 4 TVA hosts public meeting for 161 kV line in Mississippi 5 MEC selects route for 69 kV transmission line 5 PPM files request with Texas PUC against high congestion cost 5 SDG&E’s ECO project receives approval from DoI 5 PAR Electrical bags high voltage contracts from SCE 5 ABB receives USD60 million HVDC contract from AEP 6 LATIN AMERICA 6 Brazilian bank extends BRL1 billion loan for HPP lines 6 Brazilian power utility to spend BRL700 million to link wind projects 6 Argentinean regulator to hold hearing for 500 kV Santa Fe project 7 Chilean power company submits environmental request for 220 kV project 7 Chilean solar company submits environmental declaration for 110 kV line 7 Mexican energy regulator formulates smart grid plan 7 Venezuelan power utility to auction -

Global Form and Fantasy in Yiddish Literary Culture: Visions from Mexico City and Buenos Aires

Global Form and Fantasy in Yiddish Literary Culture: Visions from Mexico City and Buenos Aires by William Gertz Runyan A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Comparative Literature) in the University of Michigan 2019 Doctoral Committee: Professor Mikhail Krutikov, Chair Professor Tomoko Masuzawa Professor Anita Norich Professor Mauricio Tenorio Trillo, University of Chicago William Gertz Runyan [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0003-3955-1574 © William Gertz Runyan 2019 Acknowledgements I would like to express my gratitude to my dissertation committee members Tomoko Masuzawa, Anita Norich, Mauricio Tenorio and foremost Misha Krutikov. I also wish to thank: The Department of Comparative Literature, the Jean and Samuel Frankel Center for Judaic Studies and the Rackham Graduate School at the University of Michigan for providing the frameworks and the resources to complete this research. The Social Science Research Council for the International Dissertation Research Fellowship that enabled my work in Mexico City and Buenos Aires. Tamara Gleason Freidberg for our readings and exchanges in Coyoacán and beyond. Margo and Susana Glantz for speaking with me about their father. Michael Pifer for the writing sessions and always illuminating observations. Jason Wagner for the vegetables and the conversations about Yiddish poetry. Carrie Wood for her expert note taking and friendship. Suphak Chawla, Amr Kamal, Başak Çandar, Chris Meade, Olga Greco, Shira Schwartz and Sara Garibova for providing a sense of community. Leyenkrayz regulars past and present for the lively readings over the years. This dissertation would not have come to fruition without the support of my family, not least my mother who assisted with formatting. -

The Volcanic Ash Soils of Chile

' I EXPANDED PROGRAM OF TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE No. 2017 Report to the Government of CHILE THE VOLCANIC ASH SOILS OF CHILE FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS ROMEM965 -"'^ .Y--~ - -V^^-.. -r~ ' y Report No. 2017 Report CHT/TE/LA Scanned from original by ISRIC - World Soil Information, as ICSU World Data Centre for Soils. The purpose is to make a safe depository for endangered documents and to make the accrued information available for consultation, following Fair Use Guidelines. Every effort is taken to respect Copyright of the materials within the archives where the identification of the Copyright holder is clear and, where feasible, to contact the originators. For questions please contact [email protected] indicating the item reference number concerned. REPORT TO THE GOVERNMENT OP CHILE on THE VOLCANIC ASH SOILS OP CHILE Charles A. Wright POOL ANL AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OP THE UNITEL NATIONS ROME, 1965 266I7/C 51 iß - iii - TABLE OP CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 1 RECOMMENDATIONS 1 BACKGROUND INFORMATION 3 The nature and composition of volcanic landscapes 3 Vbloanio ash as a soil forming parent material 5 The distribution of voloanic ash soils in Chile 7 Nomenclature used in this report 11 A. ANDOSOLS OF CHILE» GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS, FORMATIVE ENVIRONMENT, AND MAIN KINDS OF SOIL 11 1. TRUMAO SOILS 11 General characteristics 11 The formative environment 13 ÈS (i) Climate 13 (ii) Topography 13 (iii) Parent materials 13 (iv) Natural plant cover 14 (o) The main kinds of trumao soils ' 14 2. NADI SOILS 16 General characteristics 16 The formative environment 16 tö (i) Climat* 16 (ii) Topograph? and parent materials 17 (iii) Natural plant cover 18 B. -

Fish Surface Activity and Pursuit-Plunging by Olivaceous Cormorants

SHORT COMMUNICATIONS 327 At the Missouri site, eagles had access to large numbers of crippled and dead geese, which presumably were the primary source oflead shot. In South Dakota, Steenhof(1976) reported finding waterfowl remains in 285 of 363 egested pellets including 10 (2.7%) with lead shot. Based upon her observations, she concluded eagles obtained most of the waterfowl in upland fields. Likewise, at our Nebraska site, eagles ate waterfowl that had been feeding in upland fields (obtained by kleptoparasitizing other raptors [Jorde and Lingle, in press]). In March 1980, they also scavenged waterfowl that had died of avian cholera (Lingle and Krapu 1986). Infrequent ingestion of lead shot by Bald Eagles in Nebraska probably stems from a low incidence of lead shot among waterfowl wintering along the Platte and North Platte rivers. The frequency of occurrence of lead shot in wintering waterfowl in Nebraska is not known; however, only about 1% of waterfowl wintering in the Texas High Plains region during the same period had lead shot in their digestive tracts (Wallace et al. 1983). It is probable that field-feeding Mallards obtained in lightly hunted uplands contain fewer lead shot than cripples or segments of the population feeding principally in wetlands where hunting activity and lead shot contamination arc likely to be concentrated. Acknowledgments.-We thank the following field technicians: R. Atkins, J. Cochnar, M. Hay, C. House, D. Janke, D. Jenson, and W. Norling. T. Baskett, D. Johnson, D. Jorde, and P. Pietz critically reviewed the manuscript. LITERATURE CITED GRIFFIN,C. R., T. S. BASKETT,AND R. -

Hemiptera: Heteroptera) of Magallanes Region: Checklist and Identification Key to the Species

Anales Instituto Patagonia (Chile), 2016. Vol. 44(1):39-42 39 The Coreoidea Leach, 1815 (Hemiptera: Heteroptera) of Magallanes Region: Checklist and identification key to the species Los Coreoidea Leach, 1815 (Hemiptera: Heteroptera) de la Región de Magallanes: Lista de especies y clave de identificación Eduardo I. Faúndez1,2 Abstract Slater, 1995), and several species are economically Members of the Coreoidea of Magallanes Region important; there are, however, also cases in which are listed. First records in the Magallanes Region are species of this superfamily have been recorded provided for Harmostes (Neoharmostes) procerus feeding on carrion and dung (Mitchell, 2000). Berg, 1878 and Althos nigropunctatus (Signoret, Additionally, biting humans has been recorded 1864). It is concluded that three species classified in members of this group (Faúndez & Carvajal, in three genera and two families are present in the 2011). In Chile, the Coreoidea is represented by region. A key to the species is provided. two families, the Coreidae and Rhopalidae, and the major diversity for this group is found in the central Key words: Coreidae, Rhopalidae, Distribution, zone of the country (Faúndez, 2015b). New records, Chile. In Magallanes, very little is known about the species of this superfamily, and actually there is Resumen only one species officially recorded from the area: Se listan los Coreoidea de la Region de Magallanes. the dunes bug, Eldarca nigroscutellata Faúndez, Se entregan los primeros registros para la región 2015 (Coreidae). The purpose of this contribution de Harmostes (Neoharmostes) procerus Berg, is to provide an update of this group in the 1878 y Althos nigropunctatus (Signoret, 1864). -

Impact of Extreme Weather Events on Aboveground Net Primary Productivity and Sheep Production in the Magellan Region, Southernmost Chilean Patagonia

geosciences Article Impact of Extreme Weather Events on Aboveground Net Primary Productivity and Sheep Production in the Magellan Region, Southernmost Chilean Patagonia Pamela Soto-Rogel 1,* , Juan-Carlos Aravena 2, Wolfgang Jens-Henrik Meier 1, Pamela Gross 3, Claudio Pérez 4, Álvaro González-Reyes 5 and Jussi Griessinger 1 1 Institute of Geography, Friedrich–Alexander-University of Erlangen–Nürnberg, 91054 Erlangen, Germany; [email protected] (W.J.-H.M.); [email protected] (J.G.) 2 Centro de Investigación Gaia Antártica, Universidad de Magallanes, Punta Arenas 6200000, Chile; [email protected] 3 Servicio Agrícola y Ganadero (SAG), Punta Arenas 6200000, Chile; [email protected] 4 Private Consultant, Punta Arenas 6200000, Chile; [email protected] 5 Hémera Centro de Observación de la Tierra, Escuela de Ingeniería Forestal, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad Mayor, Camino La Pirámide 5750, Huechuraba, Santiago 8580745, Chile; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 28 June 2020; Accepted: 13 August 2020; Published: 16 August 2020 Abstract: Spatio-temporal patterns of climatic variability have effects on the environmental conditions of a given land territory and consequently determine the evolution of its productive activities. One of the most direct ways to evaluate this relationship is to measure the condition of the vegetation cover and land-use information. In southernmost South America there is a limited number of long-term studies on these matters, an incomplete network of weather stations and almost no database on ecosystems productivity. In the present work, we characterized the climate variability of the Magellan Region, southernmost Chilean Patagonia, for the last 34 years, studying key variables associated with one of its main economic sectors, sheep production, and evaluating the effect of extreme weather events on ecosystem productivity and sheep production. -

Chile: a Journey to the End of the World in Search of Temperate Rainforest Giants

Eliot Barden Kew Diploma Course 53 July 2017 Chile: A Journey to the end of the world in search of Temperate Rainforest Giants Valdivian Rainforest at Alerce Andino Author May 2017 1 Eliot Barden Kew Diploma Course 53 July 2017 Table of Contents 1. Title Page 2. Contents 3. Table of Figures/Introduction 4. Introduction Continued 5. Introduction Continued 6. Aims 7. Aims Continued / Itinerary 8. Itinerary Continued / Objective / the Santiago Metropolitan Park 9. The Santiago Metropolitan Park Continued 10. The Santiago Metropolitan Park Continued 11. Jardín Botánico Chagual / Jardin Botanico Nacional, Viña del Mar 12. Jardin Botanico Nacional Viña del Mar Continued 13. Jardin Botanico Nacional Viña del Mar Continued 14. Jardin Botanico Nacional Viña del Mar Continued / La Campana National Park 15. La Campana National Park Continued / Huilo Huilo Biological Reserve Valdivian Temperate Rainforest 16. Huilo Huilo Biological Reserve Valdivian Temperate Rainforest Continued 17. Huilo Huilo Biological Reserve Valdivian Temperate Rainforest Continued 18. Huilo Huilo Biological Reserve Valdivian Temperate Rainforest Continued / Volcano Osorno 19. Volcano Osorno Continued / Vicente Perez Rosales National Park 20. Vicente Perez Rosales National Park Continued / Alerce Andino National Park 21. Alerce Andino National Park Continued 22. Francisco Coloane Marine Park 23. Francisco Coloane Marine Park Continued 24. Francisco Coloane Marine Park Continued / Outcomes 25. Expenditure / Thank you 2 Eliot Barden Kew Diploma Course 53 July 2017 Table of Figures Figure 1.) Valdivian Temperate Rainforest Alerce Andino [Photograph; Author] May (2017) Figure 2. Map of National parks of Chile Figure 3. Map of Chile Figure 4. Santiago Metropolitan Park [Photograph; Author] May (2017) Figure 5. -

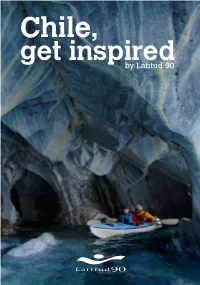

Latitud 90 Get Inspired.Pdf

Dear reader, To Latitud 90, travelling is a learning experience that transforms people; it is because of this that we developed this information guide about inspiring Chile, to give you the chance to encounter the places, people and traditions in most encompassing and comfortable way, while always maintaining care for the environment. Chile offers a lot do and this catalogue serves as a guide to inform you about exciting, adventurous, unique, cultural and entertaining activities to do around this beautiful country, to show the most diverse and unique Chile, its contrasts, the fascinating and it’s remoteness. Due to the fact that Chile is a country known for its long coastline of approximately 4300 km, there are some extremely varying climates, landscapes, cultures and natures to explore in the country and very different geographical parts of the country; North, Center, South, Patagonia and Islands. Furthermore, there is also Wine Routes all around the country, plus a small chapter about Chilean festivities. Moreover, you will find the most important general information about Chile, and tips for travellers to make your visit Please enjoy reading further and get inspired with this beautiful country… The Great North The far north of Chile shares the border with Peru and Bolivia, and it’s known for being the driest desert in the world. Covering an area of 181.300 square kilometers, the Atacama Desert enclose to the East by the main chain of the Andes Mountain, while to the west lies a secondary mountain range called Cordillera de la Costa, this is a natural wall between the central part of the continent and the Pacific Ocean; large Volcanoes dominate the landscape some of them have been inactive since many years while some still present volcanic activity. -

Análisis De La Influencia De Los Fenómenos Climáticos Niño Y Niña Sobre Ocurrencia De Incendios Forestales En La Provincia De Llanquihue, Región De Los Lagos

Análisis de la influencia de los fenómenos climáticos Niño y Niña sobre ocurrencia de incendios forestales en la provincia de Llanquihue, Región de Los Lagos Patrocinante: Sr. Juvenal Bosnich Trabajo de Titulación presentado como parte de los requisitos para optar al Título de Ingeniero Forestal. RAFAEL ALFREDO AVARIA VÁSQUEZ Valdivia 2012 Índice de materias Página 1 INTRODUCCIÓN 1 2 REVISIONBIBLIOGRÁFICA 3 2.1 Cambio Climático 3 2.2 Fenómeno del Niño 4 2.3 Fenómeno de la Niña 4 3 MATERIAL Y MÉTODOS 6 3.1 Material 6 3.1.1 Áreadeestudio 6 3.1.2 Ubicación de las estaciones meteorológicas 6 3.1.3 Clima regional 7 3.1.4 Vegetación 7 3.1.5 Superficie por tipo de uso en la Región de Los Lagos 8 3.2 MÉTODO 8 4. RESULTADOS Y DISCUSIÓN 9 4.1 Ocurrencia de incendios en función de la temperatura media 9 máxima en temporadas Niña-Niño 4.2 Ocurrencia de incendios en función de la Pluviometría en emporadas 11 Niña-Niño 4.3 Superficie total dañada según vegetación durante temporadas 12 Niña-Niño 5. CONCLUSIONES 14 6. BIBLIOGRAFÍA 16 ANEXOS 1 Abstract 2 Ocurrencia de incendios por temporada. 3 Ocurrencia histórica de fenómenos climáticos. 4 Temperatura media máxima y pluviometría mensual en la última década. Calificación del Comité de Titulación Nota Patrocinante: Sr. Juvenal Bosnich A. __67__ Informante: Sr. Jorge Cabrera P. __65__ Informante: Sr. Antonio Lara A. __64__ El Patrocinante acredita que el presente Trabajo de Titulación cumple con los requisitos de contenido y de forma contemplados en el Reglamento de Titulación de la Escuela. -

Catalogue of Chilean Centipedes (Myriapoda, Chilopoda)

90 (1) · April 2018 pp. 27–37 Catalogue of Chilean centipedes (Myriapoda, Chilopoda) Emmanuel Vega-Román1,2* and Víctor Hugo Ruiz2 1 Universidad del Bío Bío, Facultad de Educación, Av. Casilla 5-C, Collao 1202, Concepción, Región del Bío Bío, Chile 2 Universidad de Concepción, Facultad de Ciencias Naturales y Oceanográficas, Departamento de Zoología, Barrio Universitario, Sin dirección. Casilla 160-C, Concepción, Bío Bío, Chile * Corresponding author, e-mail: [email protected] Received 11 January 2017 | Accepted 22 March 2018 Published online at www.soil-organisms.de 1 April 2018 | Printed version 15 April 2018 Abstract A review of all literature, published between 1847 and 2016, provides a comprehensive inventory of research on Chilean Chilo- poda. A total of 4 orders, 10 families, 28 genera and 70 species were recorded, highlighting the diversity of Chilopoda species in Chile. The geographical distribution and habitat preferences of all species are given with reference to the literature. Keywords Arthropoda | Chilopoda | Chile | taxonomy | biogeography 1. Introduction cross-referenced against ChiloBase 2.0, an international database of Chilopoda taxonomy (Bonato et al. 2016). The Chilopoda are a group of arthropods distributed Where species identification was considered ambiguous worldwide, occupying a wide variety of ecosystems with in the literature, it was excluded from the present analysis to the exception of polar areas (Edgecombe & Giribet 2007). avoid erroneous or non-reliable results. The exclusion cri- They are nocturnal arthropods, preferring areas with teria considered that most records were taken directly from high humidity, even inhabiting intertidal and supratidal the literature without the possibility to check the material zones (Barber 2009). -

Invaders Without Frontiers: Cross-Border Invasions of Exotic Mammals

Biological Invasions 4: 157–173, 2002. © 2002 Kluwer Academic Publishers. Printed in the Netherlands. Review Invaders without frontiers: cross-border invasions of exotic mammals Fabian M. Jaksic1,∗, J. Agust´ın Iriarte2, Jaime E. Jimenez´ 3 & David R. Mart´ınez4 1Center for Advanced Studies in Ecology & Biodiversity, Pontificia Universidad Catolica´ de Chile, Casilla 114-D, Santiago, Chile; 2Servicio Agr´ıcola y Ganadero, Av. Bulnes 140, Santiago, Chile; 3Laboratorio de Ecolog´ıa, Universidad de Los Lagos, Casilla 933, Osorno, Chile; 4Centro de Estudios Forestales y Ambientales, Universidad de Los Lagos, Casilla 933, Osorno, Chile; ∗Author for correspondence (e-mail: [email protected]; fax: +56-2-6862615) Received 31 August 2001; accepted in revised form 25 March 2002 Key words: American beaver, American mink, Argentina, Chile, European hare, European rabbit, exotic mammals, grey fox, muskrat, Patagonia, red deer, South America, wild boar Abstract We address cross-border mammal invasions between Chilean and Argentine Patagonia, providing a detailed history of the introductions, subsequent spread (and spread rate when documented), and current limits of mammal invasions. The eight species involved are the following: European hare (Lepus europaeus), European rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus), wild boar (Sus scrofa), and red deer (Cervus elaphus) were all introduced from Europe (Austria, France, Germany, and Spain) to either or both Chilean and Argentine Patagonia. American beaver (Castor canadensis) and muskrat (Ondatra zibethicus) were introduced from Canada to Argentine Tierra del Fuego Island (shared with Chile). The American mink (Mustela vison) apparently was brought from the United States of America to both Chilean and Argentine Patagonia, independently. The native grey fox (Pseudalopex griseus) was introduced from Chilean to Argentine Tierra del Fuego. -

Redalyc.Paleodistribución Del Alerce Y Ciprés De Las Guaitecas Durante

Andean Geology ISSN: 0718-7092 [email protected] Servicio Nacional de Geología y Minería Chile Villagrán, Carolina; León, Ana; Roig, Fidel A. Paleodistribución del alerce y ciprés de las Guaitecas durante períodos interestadiales de la Glaciación Llanquihue: provincias de Llanquihue y Chiloé, Región de Los Lagos, Chile Andean Geology, vol. 31, núm. 1, julio, 2004, pp. 133-151 Servicio Nacional de Geología y Minería Santiago, Chile Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=173918528008 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto Paleodistribución del alerce y ciprés de las Guaitecas durante períodos interestadiales de la Glaciación Llanquihue: provin- cias de Llanquihue y Chiloé, Región de Los Lagos, Chile Carolina Villagrán Laboratorio de Palinología, Facultad de Ciencias, Ana León Universidad de Chile, Casilla 653, Santiago, Chile [email protected] [email protected] Fidel A. Roig Laboratorio de Dendrocronología e Historia Ambiental, IANIGLA- CONICET, CC 330, Mendoza (5500), Argentina [email protected] RESUMEN Este estudio tiene como propósito dar a conocer recientes hallazgos paleobotánicos en el Seno de Reloncaví y costas oriental y norte de la isla Grande de Chiloé. Se trata de ocho sitios con troncos subfósiles de alerce (Fitzroya cupressoides (Mol.) Johnst.) y ciprés de las Guaitecas (Pilgerodendron uviferum (D. Don) Florin), in situ y en muy buen estado de preservación. De acuerdo a seis dataciones radiocarbónicas preliminares, con edades finitas entre 42.600 y 49.780 C14 años AP, los depósitos con los troncos corresponderían a lapsos interestadiales del período Llanquihue medio de la última glaciación (estadio isotópico 3).