Zeitschrift Für Säugetierkunde

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Global Form and Fantasy in Yiddish Literary Culture: Visions from Mexico City and Buenos Aires

Global Form and Fantasy in Yiddish Literary Culture: Visions from Mexico City and Buenos Aires by William Gertz Runyan A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Comparative Literature) in the University of Michigan 2019 Doctoral Committee: Professor Mikhail Krutikov, Chair Professor Tomoko Masuzawa Professor Anita Norich Professor Mauricio Tenorio Trillo, University of Chicago William Gertz Runyan [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0003-3955-1574 © William Gertz Runyan 2019 Acknowledgements I would like to express my gratitude to my dissertation committee members Tomoko Masuzawa, Anita Norich, Mauricio Tenorio and foremost Misha Krutikov. I also wish to thank: The Department of Comparative Literature, the Jean and Samuel Frankel Center for Judaic Studies and the Rackham Graduate School at the University of Michigan for providing the frameworks and the resources to complete this research. The Social Science Research Council for the International Dissertation Research Fellowship that enabled my work in Mexico City and Buenos Aires. Tamara Gleason Freidberg for our readings and exchanges in Coyoacán and beyond. Margo and Susana Glantz for speaking with me about their father. Michael Pifer for the writing sessions and always illuminating observations. Jason Wagner for the vegetables and the conversations about Yiddish poetry. Carrie Wood for her expert note taking and friendship. Suphak Chawla, Amr Kamal, Başak Çandar, Chris Meade, Olga Greco, Shira Schwartz and Sara Garibova for providing a sense of community. Leyenkrayz regulars past and present for the lively readings over the years. This dissertation would not have come to fruition without the support of my family, not least my mother who assisted with formatting. -

Hemiptera: Heteroptera) of Magallanes Region: Checklist and Identification Key to the Species

Anales Instituto Patagonia (Chile), 2016. Vol. 44(1):39-42 39 The Coreoidea Leach, 1815 (Hemiptera: Heteroptera) of Magallanes Region: Checklist and identification key to the species Los Coreoidea Leach, 1815 (Hemiptera: Heteroptera) de la Región de Magallanes: Lista de especies y clave de identificación Eduardo I. Faúndez1,2 Abstract Slater, 1995), and several species are economically Members of the Coreoidea of Magallanes Region important; there are, however, also cases in which are listed. First records in the Magallanes Region are species of this superfamily have been recorded provided for Harmostes (Neoharmostes) procerus feeding on carrion and dung (Mitchell, 2000). Berg, 1878 and Althos nigropunctatus (Signoret, Additionally, biting humans has been recorded 1864). It is concluded that three species classified in members of this group (Faúndez & Carvajal, in three genera and two families are present in the 2011). In Chile, the Coreoidea is represented by region. A key to the species is provided. two families, the Coreidae and Rhopalidae, and the major diversity for this group is found in the central Key words: Coreidae, Rhopalidae, Distribution, zone of the country (Faúndez, 2015b). New records, Chile. In Magallanes, very little is known about the species of this superfamily, and actually there is Resumen only one species officially recorded from the area: Se listan los Coreoidea de la Region de Magallanes. the dunes bug, Eldarca nigroscutellata Faúndez, Se entregan los primeros registros para la región 2015 (Coreidae). The purpose of this contribution de Harmostes (Neoharmostes) procerus Berg, is to provide an update of this group in the 1878 y Althos nigropunctatus (Signoret, 1864). -

YPF Luz Canadon Leon SLIP COMPILED FINAL 27Jun19

Supplemental Lenders Information Package (SLIP) Cañadon Leon Windfarm 27 June 2019 Project No.: 0511773 The business of sustainability Document details Document title Supplemental Lenders Information Package (SLIP) Document subtitle Cañadon Leon Windfarm Project No. 0511773 Date 27 June 2019 Version 03 Author ERM Client Name YPF Luz Document history ERM approval to issue Version Revision Author Reviewed by Name Date Comments Draft 01 ERM Camille Maclet For internal review Draft 02 ERM Camille Maclet C. Maclet 12/06/2019 For client comments Final 03 ERM Camille Maclet C. Maclet 27/06/2019 Final issue www.erm.com Version: 03 Project No.: 0511773 Client: YPF Luz 27 June 2019 Signature Page 27 June 2019 Supplemental Lenders Information Package (SLIP) Cañadon Leon Windfarm Luisa Perez Gorospe Camille Maclet Project Manager Partner in Charge ERM Argentina S.A. #2677 Cabildo Ave. C1428AAI, Buenos Aires City Argentina © Copyright 2019 by ERM Worldwide Group Ltd and / or its affiliates (“ERM”). All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form, or by any means, without the prior written permission of ERM www.erm.com Version: 03 Project No.: 0511773 Client: YPF Luz 27 June 2019 SUPPLEMENTAL LENDERS INFORMATION PACKAGE (SLIP) YPF LUZ Cañadon Leon Windfarm TABLE OF CONTENTS ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS .................................................................................................................... A EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................................................................... -

Impact of Extreme Weather Events on Aboveground Net Primary Productivity and Sheep Production in the Magellan Region, Southernmost Chilean Patagonia

geosciences Article Impact of Extreme Weather Events on Aboveground Net Primary Productivity and Sheep Production in the Magellan Region, Southernmost Chilean Patagonia Pamela Soto-Rogel 1,* , Juan-Carlos Aravena 2, Wolfgang Jens-Henrik Meier 1, Pamela Gross 3, Claudio Pérez 4, Álvaro González-Reyes 5 and Jussi Griessinger 1 1 Institute of Geography, Friedrich–Alexander-University of Erlangen–Nürnberg, 91054 Erlangen, Germany; [email protected] (W.J.-H.M.); [email protected] (J.G.) 2 Centro de Investigación Gaia Antártica, Universidad de Magallanes, Punta Arenas 6200000, Chile; [email protected] 3 Servicio Agrícola y Ganadero (SAG), Punta Arenas 6200000, Chile; [email protected] 4 Private Consultant, Punta Arenas 6200000, Chile; [email protected] 5 Hémera Centro de Observación de la Tierra, Escuela de Ingeniería Forestal, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad Mayor, Camino La Pirámide 5750, Huechuraba, Santiago 8580745, Chile; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 28 June 2020; Accepted: 13 August 2020; Published: 16 August 2020 Abstract: Spatio-temporal patterns of climatic variability have effects on the environmental conditions of a given land territory and consequently determine the evolution of its productive activities. One of the most direct ways to evaluate this relationship is to measure the condition of the vegetation cover and land-use information. In southernmost South America there is a limited number of long-term studies on these matters, an incomplete network of weather stations and almost no database on ecosystems productivity. In the present work, we characterized the climate variability of the Magellan Region, southernmost Chilean Patagonia, for the last 34 years, studying key variables associated with one of its main economic sectors, sheep production, and evaluating the effect of extreme weather events on ecosystem productivity and sheep production. -

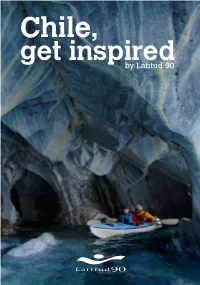

Latitud 90 Get Inspired.Pdf

Dear reader, To Latitud 90, travelling is a learning experience that transforms people; it is because of this that we developed this information guide about inspiring Chile, to give you the chance to encounter the places, people and traditions in most encompassing and comfortable way, while always maintaining care for the environment. Chile offers a lot do and this catalogue serves as a guide to inform you about exciting, adventurous, unique, cultural and entertaining activities to do around this beautiful country, to show the most diverse and unique Chile, its contrasts, the fascinating and it’s remoteness. Due to the fact that Chile is a country known for its long coastline of approximately 4300 km, there are some extremely varying climates, landscapes, cultures and natures to explore in the country and very different geographical parts of the country; North, Center, South, Patagonia and Islands. Furthermore, there is also Wine Routes all around the country, plus a small chapter about Chilean festivities. Moreover, you will find the most important general information about Chile, and tips for travellers to make your visit Please enjoy reading further and get inspired with this beautiful country… The Great North The far north of Chile shares the border with Peru and Bolivia, and it’s known for being the driest desert in the world. Covering an area of 181.300 square kilometers, the Atacama Desert enclose to the East by the main chain of the Andes Mountain, while to the west lies a secondary mountain range called Cordillera de la Costa, this is a natural wall between the central part of the continent and the Pacific Ocean; large Volcanoes dominate the landscape some of them have been inactive since many years while some still present volcanic activity. -

“Diagnóstico De La Pesca Recreativa En El Río Palena, Región De Los

“Diagnóstico de la Pesca Recreativa en el Río Palena, Región de Los Lagos, Chile” Tesis para optar al Título de Ingeniero en Acuicultura. Profesor Patrocinante: Dr. Sandra Bravo MARCELO ALEJANDRO CÁCERES LANGENBACH PUERTO MONTT, CHILE 2013 AGRADECIMIENTOS Agradecer a mi profesora patrocinante Dr. Sandra Bravo por permitirme participar en el proyecto FIC 30115221 de "Determinación y Evaluación de los factores que inciden en los Stock de Salmónidos, objeto de la pesca recreativa en el Río Palena (X Región), en un marco de sustentabilidad económica y ambiental" ,el cual me permitió realizar mi tesis. También quisiera darle las gracias por sus conocimientos entregados, sus horas gastadas en explicarme las dudas y sus correcciones. A mis profesores informantes María Teresa Silva y Alejandro Sotomayor por sus correcciones y ayuda entregada para realizar de mejor forma esta tesis. Al grupo de trabajo del proyecto Carlos Leal, Verónica Pozo, Carolina Rodríguez por sus aportes tanto en mi practica como en la tesis y por hacer agradables las salidas a terreno. A los colaboradores internacionales profesor Ken Whelan y Trygve Poppe por sus aportes tanto en conocimiento como de las legislaciones en sus respectivos países. A mis compañeros de tesis Elba Cayumil y Cristian Monroy por su compañía, y por los años de amistad. A mi amigo Pablo por su apoyo y ayuda gracias. Quisiera darle las gracias a mi tío René por su tiempo y por sus horas de estudios entregadas en ayudarme. Por último agradecerle a mi mamá Marlis por todo su cariño, por tu apoyo, por estar siempre cuando te necesito, a mi papá Egidio porque nunca me falto nada, a mi hermano Egidio, a mí cuñada Anita y a mis sobrinos seba y pipe por todo el cariño. -

Portfolio of Properties

Portfolio of Properties VALLE CALIFORNIA · LAGO ESPOLÓN · RÍO PALENA · JEINIMENI · TORTEL MELIMOYU · LOS LEONES, Patagonia Sur is a conservation- oriented company that invests in, protects, and enhances scenically remarkable and ecologically valuable properties in Chilean Patagonia. Visit us at www.PatagoniaSur.com OPPORTUNITY | PATAGONIA 03 Chilean Patagonia is positioned as an attractive investment hub. Global interest in the zone´s conservation has propelled projects that aim to the shape the future of this magical and unexplored place while preserving the integrity of its past. QUALITY TIME | PATAGONIA 04 Disconnect from the world and reconnect with your family and friends while enjoying the pristine landscapes of these incredible properties. PORTFOLIO OF PROPERTIES | MAP 05 To Santiago 638 mi Puerto Montt Chiloé Chaitén LAGO ESPOLÓN RÍO PALENA VALLE CALIFORNIA MELIMOYU PATAGONIA Coyhaique ARGENTINA Balmaceda PACIFIC OCEAN Lake General Carrera LOS LEONES Chile Chico JEINIMENI Northern Ice Field TORTEL Valle California 8,000 acres VALLE CALIFORNIA | REGIONAL MAP 07 Chaitén Esquel LAGO ESPOLON PACIFIC OCEAN Lake Espolón Futaleufú Futaleufú River Lake Yelcho ARGENTINA Villa Santa Lucía Puerto Ramírez Frío River RÍO PALENA Palena Palena VALLE CALIFORNIA River Tigre River LAKE REGION Azul River AYSEN REGION Palena River LAGO PALENA La Junta NATIONAL RESERVE VALLE CALIFORNIA | GETTING THERE 08 3:30 hours / 2 stops ACCESS ARGENTINA THROUGH PUERTO VALLE SCL PALENA CHILE MONTT CALIFORNIA From Santiago SANTIAGO BUENOS AIRES to Valle 2 hrs 1 -

The Patagonian Cordillera and Its Main Rivers, Between 41° and 48° South Latitude (Continued) Author(S): Hans Steffen Source: the Geographical Journal, Vol

The Patagonian Cordillera and Its Main Rivers, between 41° and 48° South Latitude (Continued) Author(s): Hans Steffen Source: The Geographical Journal, Vol. 16, No. 2 (Aug., 1900), pp. 185-209 Published by: geographicalj Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1774557 Accessed: 27-06-2016 04:52 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers), Wiley are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Geographical Journal This content downloaded from 131.247.112.3 on Mon, 27 Jun 2016 04:52:42 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms ( 185 ) THE PATAGONIAN CORDILLERA AND ITS MAIN RIVERS, BETWEEN 41? AND 48? SOUTH LATITUDE.* By Dr. HANS STEFFEN. To return to the lacustrine basin of the Puelo valley, we see that it is confined on its northern side by the snow-clad mountain mass already mentioned, and as yet unexplored; while on its southern side runs, in a decidedly south-easterly direction, the lofty and steep barrier of the " Cordon de las Hualas," the precipitous flanks of which, towards the valley depression, offer a truly impressive sight. -

Invaders Without Frontiers: Cross-Border Invasions of Exotic Mammals

Biological Invasions 4: 157–173, 2002. © 2002 Kluwer Academic Publishers. Printed in the Netherlands. Review Invaders without frontiers: cross-border invasions of exotic mammals Fabian M. Jaksic1,∗, J. Agust´ın Iriarte2, Jaime E. Jimenez´ 3 & David R. Mart´ınez4 1Center for Advanced Studies in Ecology & Biodiversity, Pontificia Universidad Catolica´ de Chile, Casilla 114-D, Santiago, Chile; 2Servicio Agr´ıcola y Ganadero, Av. Bulnes 140, Santiago, Chile; 3Laboratorio de Ecolog´ıa, Universidad de Los Lagos, Casilla 933, Osorno, Chile; 4Centro de Estudios Forestales y Ambientales, Universidad de Los Lagos, Casilla 933, Osorno, Chile; ∗Author for correspondence (e-mail: [email protected]; fax: +56-2-6862615) Received 31 August 2001; accepted in revised form 25 March 2002 Key words: American beaver, American mink, Argentina, Chile, European hare, European rabbit, exotic mammals, grey fox, muskrat, Patagonia, red deer, South America, wild boar Abstract We address cross-border mammal invasions between Chilean and Argentine Patagonia, providing a detailed history of the introductions, subsequent spread (and spread rate when documented), and current limits of mammal invasions. The eight species involved are the following: European hare (Lepus europaeus), European rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus), wild boar (Sus scrofa), and red deer (Cervus elaphus) were all introduced from Europe (Austria, France, Germany, and Spain) to either or both Chilean and Argentine Patagonia. American beaver (Castor canadensis) and muskrat (Ondatra zibethicus) were introduced from Canada to Argentine Tierra del Fuego Island (shared with Chile). The American mink (Mustela vison) apparently was brought from the United States of America to both Chilean and Argentine Patagonia, independently. The native grey fox (Pseudalopex griseus) was introduced from Chilean to Argentine Tierra del Fuego. -

Plecoptera Y Aeglidae

Revista Chilena de Historia Natural ISSN: 0716-078X [email protected] Sociedad de Biología de Chile Chile VALDOVINOS, CLAUDIO; KIESSLING, ANDREA; MARDONES, MARÍA; MOYA, CAROLINA; OYANEDEL, ALEJANDRA; SALVO, JACQUELINE; OLMOS, VIVIANA; PARRA, ÓSCAR Distribución de macroinvertebrados (Plecoptera y Aeglidae) en ecosistemas fluviales de la Patagonia chilena: ¿Muestran señales biológicas de la evolución geomorfológica postglacial? Revista Chilena de Historia Natural, vol. 83, núm. 2, 2010, pp. 267-287 Sociedad de Biología de Chile Santiago, Chile Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=369944294009 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto DISTRIBUCIÓN DE MACROINVERTEBRADOS EN RÍOS PATAGÓNICOS 267 REVISTA CHILENA DE HISTORIA NATURAL Revista Chilena de Historia Natural 83: 267-287, 2010 © Sociedad de Biología de Chile ARTÍCULO DE INVESTIGACIÓN Distribución de macroinvertebrados (Plecoptera y Aeglidae) en ecosistemas fluviales de la Patagonia chilena: ¿Muestran señales biológicas de la evolución geomorfológica postglacial? Distribution of macroinvertebrates (Plecoptera and Aeglidae) in fluvial ecosystems of the Chilean Patagonia: Do they show biological signals of the postglacial geomorphological evolution? CLAUDIO VALDOVINOS1, 2, *, ANDREA KIESSLING1, MARÍA MARDONES3, -

Hydrological Droughts in the Southern Andes (40–45°S)

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Hydrological droughts in the southern Andes (40–45°S) from an ensemble experiment using CMIP5 and CMIP6 models Rodrigo Aguayo1, Jorge León‑Muñoz2,3*, René Garreaud4,5 & Aldo Montecinos6,7 The decrease in freshwater input to the coastal system of the Southern Andes (40–45°S) during the last decades has altered the physicochemical characteristics of the coastal water column, causing signifcant environmental, social and economic consequences. Considering these impacts, the objectives were to analyze historical severe droughts and their climate drivers, and to evaluate the hydrological impacts of climate change in the intermediate future (2040–2070). Hydrological modelling was performed in the Puelo River basin (41°S) using the Water Evaluation and Planning (WEAP) model. The hydrological response and its uncertainty were compared using diferent combinations of CMIP projects (n = 2), climate models (n = 5), scenarios (n = 3) and univariate statistical downscaling methods (n = 3). The 90 scenarios projected increases in the duration, hydrological defcit and frequency of severe droughts of varying duration (1 to 6 months). The three downscaling methodologies converged to similar results, with no signifcant diferences between them. In contrast, the hydroclimatic projections obtained with the CMIP6 and CMIP5 models found signifcant climatic (greater trends in summer and autumn) and hydrological (longer droughts) diferences. It is recommended that future climate impact assessments adapt the new simulations as more CMIP6 models become available. Anthropogenic climate change has increased the probability of extreme events in the mid-latitudes of the South- ern Hemisphere, mainly those linked to severe droughts 1. Projections indicate that these drought events may increase in extent, frequency and magnitude as they superimpose on the gradual decrease in precipitation2,3 and a signifcant increase in heat waves 4. -

Trip Name: Andean River Odyssey Day by Day

ExChile Greatest Playground on Earth! 2010-2011-2012 season Trip Name: Andean River Odyssey Last Name: First Name: Email: Phone: # in group: Comments: Overview: This Chile sea kayaking vacation crosses the Andes Mountains and much of the country of Chile reaching a final destination located along the South Pacific Ocean. This is a shorter version of our Patagonia River Odyssey expedition; here we put-in below the whitewater section of the Figueroa and Palena rivers. National Geographic International Adventurist: Seven days to the Futaleufu - Trailer Slideshows: Slide Shows Day by Day: Day 1 Friday: Depart your home town: Fly to Miami and connect on an over night flight to Buenos Aires Argentina. Welcome to the warmth of the southern Hemisphere in summer. Day 2 Saturday: Travel to Trevelin, Patagonia Argentina Early morning arrival in Buenos Aires. Change airports and catch another flight to Bariloche, or Esquel Argentina. From Bariloche, a luxury bus will take you on a beautiful drive along the Patagonian lakes and mountains to Esquel. IF you fly direct to Esquel you can arrive in Trevelin with some time to enjoy the area. Trevelin, Argentina is a charming mountain village gateway just 45 minutes from Futaleufu River in Chile. Trevelin is serviced by ground transport (Bus or private taxi) from the Jet ports in Bariloche (4 hrs) or Esquel (40 min). Check into a hotel in this charming village and walk to one of several superb restaurants. Unwind, relax, and get a good nights sleep before the start of you trip 9:00 am the next morning. Day 3 Sunday March 14: Your Trip Starts at The Greatest Playground on Earth! Futaleufu Chile Awake to a breakfast at your hotel and prepare for the 9 am pick up.