Attempts to Pass a Second Anti-Evolution Law in Oklahoma

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Red-Tie Bill and the Wingless Bird: Tar Heel Baptists and the Evolution

The Daily Advance, which devoted an average of four full-page Red-Tie Bill and the Wingless Bird: columns a day to the spectacle, glowed with the glory of it all. "The Tar Heel Baptists and the evangelist's grip on the city," wrote Herbert Peele, is almost breathtaking .. The revival is the topic of conversation wherever one Evolution Controversy goes. ... The barber in h1~ chair, the salesman behind his counter, the executive at his desk,, the worker ~t ~1s bench, the laborer at his task are one and all thinking Tom Parramore and talking about religion. 0. SAUNDERS, the puckish editor of the Elizabeth City Inde• And what was the inspirational message that Pasquotank County W;pendent, ·was after the revivalists fang and claw before they could was flocking to the tabernacle twice a day, seven days a week, to hear? get their tabernacle up. He predicted that Elizabeth City was going to It was direct, simple, clear, dramatic: the world, Ham assured his have a "red-hot, rip-snorting, hell-raising, sin-busting carnival of evan• audiences, was about to come to an end. The whole temple of man's gelism" that would last for eight weeks or "as Jong as the town stands wordly achievement-all his cities, his industry, his art, his science, his for it." He declared that Evangelist Mordecai Ham's main business government-were at the brink of an utter and complete destruction there was to work on the emotions of the ignorant and then skip town from which there was no earthly or heavenly hope of being spared. -

FBHS-Journal-2010.Pdf

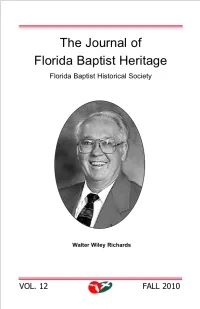

The Journal of Florida Baptist Heritage Florida Baptist Historical Society Published by the FLORIDA BAPTIST HISTORICAL SOCIETY Dr. Jerry M. Windsor, Secretary-Treasurer 5400 College Drive Graceville, Florida 32440 Board of Directors y The State Board of Missions of the Florida t e i c Baptist Convention elects the Board of e o g Directors. S l a a t c i i Rev. Joe Butler r r o t Director of Missions, Black Creek Association e s Mrs. Elaine Coats i H H t Fernandina Beach t s i t Mrs. Clysta De Armas s p i a Port Charlotte t B p Mr. Don Graham a a d Graceville i r B o Dr. Thomas Kinchen l F President, The Baptist College of Florida a e d h t Mrs. Dori Nelson i f r Miami o o l l Dr. Paul Robinson a n F Pensacola r u Rev. Guy Sanders o J Pastor, First Baptist Church, New Port Richey Dr. John Sullivan Executive Director-Treasurer Florida Baptist Convention Cover: Dr. W. Wiley Richards has been preach- ing for 56 years, taught for 36 years and has What We Can Learn about Pastoral Preaching from served 48 interims. Dr. Jerry Oswalt......................................................116 Ed Scott Jerry Windsor-A Passion to Preach, a Burden to Teach Introduction ................................................................4 Preachers ................................................................127 Jerry M. Windsor Joel R. Breidenbaugh The 1885 Preaching of Nathan A. Williams ..............6 Dr. W. Wiley Richards: He Came Teaching...........139 Thomas Field Roger C. Richards A Historical Study of Evangelist Mordecai F. Ham’s 1905-1939 Florida Meetings....................................16 s Jerry Hopkins s t t n Charles Bray Williams n e e t Greek Scholar, Pastor, Preacher...............................28 t n Charlotte Williams Sprawls n o o C The Preaching of Charles Roy Angell C “A Master Collector and Teller of Stories”..............68 Jerry E. -

THE PROHIBITION Referendufvl J

0 TA E. Volume 30, No. 1 WESTERVILLE, OHIO, JANUARY, 1929 $1.00 Per Year nor Smith complains it could have never destroyed the open saloon. But, rdETHODISTS BACK THE ANTI-SALOON LEAGUE why should the churches through their organization, the Anti-Saloon The following resolutions were passed unanimously at the recent se;:; League, which is the church in action, for the purpose of fighting the liquor sion of the W e;:t Texas Annual Conference of the M. E. Church, South: traffic, be criticised for doing its work when the organized liquor tn.ffic in "Whereas, Since the adoption of the Eighteenth Amendment, our dry pre-prohibition days was working 365 days in the year to dominate the poli forces have to some extent become disorganized, and hereby have permitted tics and government of the nation and of every state in the Union, while, the enemy of prohibition to sow tares in their social, moral and political since prohibition the outlawed liquor traffic, represented by the Association field, that, in this political crisis, at least, gives great alarm lest thereby the Against the Prohibition Amendment, headed by Curran and Stayton an.::l 'noble experiment' for which our mothers and fathers fought for a hundred John J. Raskob and Pierre S. duPont, all Republicans, are fighting in the years might be suddenly smothered, annulled and destroyed; but nation and in all the states to promote the return of the legalized sale of "Whereas, During all this trying period of indifference and disintegra booze and for the Canadian liquor "parlor" substitute -

The Scopes Trial, Antievolutionism, and the Last Crusade of William Jennings Bryan

University of Mississippi eGrove Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2012 Six Days of Twenty-Four Hours: the Scopes Trial, Antievolutionism, and the Last Crusade of William Jennings Bryan Kari Lynn Edwards Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd Part of the History of Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Edwards, Kari Lynn, "Six Days of Twenty-Four Hours: the Scopes Trial, Antievolutionism, and the Last Crusade of William Jennings Bryan" (2012). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 96. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd/96 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SIX DAYS OF TWENTY-FOUR HOURS: THE SCOPES TRIAL, ANTIEVOLUTIONISM, AND THE LAST CRUSADE OF WILLIAM JENNINGS BRYAN A Thesis presented in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Southern Studies The University of Mississippi by KARI EDWARDS May 2012 Copyright Kari Edwards 2012 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT The academic study of the Scopes Trial has always been approached from a traditional legal interpretation. This project seeks to reframe the conventional arguments surrounding the trial, treating it instead as a significant religious event, one which not only altered the course of Christian Fundamentalism and the Creationist movement, but also perpetuated Southern religious stereotypes through the intense, and largely negative, nationwide publicity it attracted. Prosecutor William Jennings Bryan's crucial role is also redefined, with his denial of a strictly literal interpretation of Genesis during the trial serving as the impetus for the shift toward ultra- conservatism and young-earth Creationism within the movement after 1925. -

Creationism in Twentieth-Century America: the Antievolution Pamphlets of William Bell Riley William Vance Trollinger University of Dayton, [email protected]

University of Dayton eCommons History Faculty Publications Department of History 1995 Creationism in Twentieth-century America: The Antievolution Pamphlets of William Bell Riley William Vance Trollinger University of Dayton, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.udayton.edu/hst_fac_pub Part of the History Commons eCommons Citation Trollinger, William Vance, "Creationism in Twentieth-century America: The Antievolution Pamphlets of William Bell Riley" (1995). History Faculty Publications. 5. https://ecommons.udayton.edu/hst_fac_pub/5 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. INTRODUCTION It is difficult to overstate William Bell Riley's importance to the early fundamentalist movement; it is well-nigh impossible to exaggerate his prodigious energy. In the years between the world wars, when he was in his 60s and 70s and pastor of a church with thousands of members, Riley founded and directed the first inter denominational organization of fundamentalists, served as an active leader of the fundamentalist faction in the Northern Bap tist Convention, edited a variety of fundamentalist periodicals, wrote innumerable books and articles and pamphlets (including, in the less-polemical vein, a forty-volume exposition ofthe entire Bible), presided over a fundamentalist Bible school and its ex panding network of churches, and masterminded a fundamental ist takeover of the Minnesota Baptist Convention. Besides all this, in these years William Bell Riley also established himself as one ofthe leading antievolutionists in America. -

She's the Jazz: an Exploration of Dance and Society in the Age of the Flapper Jillian Terry Western Kentucky University, [email protected]

Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® Honors College Capstone Experience/Thesis Honors College at WKU Projects Spring 2019 She's the Jazz: An Exploration of Dance and Society in the Age of the Flapper Jillian Terry Western Kentucky University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/stu_hon_theses Part of the Dance Commons, Performance Studies Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Terry, Jillian, "She's the Jazz: An Exploration of Dance and Society in the Age of the Flapper" (2019). Honors College Capstone Experience/Thesis Projects. Paper 811. https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/stu_hon_theses/811 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College Capstone Experience/ Thesis Projects by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SHE’S THE JAZZ: AN EXPLORATION OF DANCE AND SOCIETY IN THE AGE OF THE FLAPPER A Capstone Project Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Bachelor of Arts with Honors College Graduate Distinction at Western Kentucky University By Jillian C. Terry May 2019 ***** CE/T Committee: Professor Amanda Clark, Chair Assistant Professor Anna Patsfall Copyright by Jillian C. Terry 2019 ii I dedicate this written thesis to my parents, Samuel Robert and Christy Terry, who have supported me wholly with unfailing love in every adventure along the way. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My work would not be -

Book Reviews

Book Reviews theories about language and the power of scripture as the Word of God in a modern context, liberal evangelicals’ commitment to social reform as an expression of piety and an outgrowth of Christian conversion, the liberal evangelical curriculum at the Union School of Religion and its struggle ðand ultimate failureÞ to maintain a distinct evangelical identity, the emergence of a prophetic and confrontational fundamentalist style in New York City as exemplified by the ministry and public preaching of John Roach Straton, and a concluding chapter on Harry Emerson Fosdick’s doomed efforts to maintain a robust form of liberal evangelicalism at Riverside Church. It is hard not to read this book as a declension narrative, despite Bowman’s assertion that liberal evangelicals did not capitulate to modernity or did not see themselves as “selling out” to a secular culture. Almost all of the figures he looks at or the liberal attempts to combine a prophetic commitment to social reform, a priestly emphasis on pastoral work, and personal spiritual conversion and growth end in disappointment or failure or a loss of a distinctive evangelical identity, which they had sought so assiduously to retain. So rather than demonstrating that evan- gelicalism is robust when it imagines itself diverse, Bowman’s work instead demon- strates the difficulty liberals encountered who wanted to maintain an evangelical identity and how hard it was to occupy a treacherous middle ground. That seems to be the fate of liberal evangelicalism narrated in this very important if not quite per- suasive book. CURTIS EVANS, University of Chicago. -

Historical Society Transitions

PRIMARY SOURCE Non Profit Organization American Baptist Historical Society U.S. Postage 3001 Mercer University Drive PAID Atlanta GA 30341 Athens, GA Permit No. 11 Volume 18, No. 4 Fall, 2020 Historical Society Transitions: New Members on Farewell to Two Staff Members ABHS Board of Managers At the end of December we will bid farewell to Felipe Candelaria is pastor two valued members of the ABHS team. of Iglesia Bautista de Quebrada in For almost nine years, Jan Winfield has been Puerto Rico. He has been on the ABHS’s voice on the phone, responder to emails, Board of General Ministries, the and poster on social media. Jan has prepared and ABC Biennial Planning sent countless church anniversary certificates and Committee, the Hispanic Caucus, member letters, coordinated arrangements for and the Puerto Rico Region Board of Managers meetings and ABHS Biennial Board. Meeting activities, and produced dozens of news- Beverly Fink has been active with ABHS for letters and fundraising mailings. If you’ve re- many years. “Because of my long involvement ceived it from ABHS, Jan has probably touched it! and interest in American During her tenure Jan developed an apprecia- Baptists, I appreciate and value tion of Baptist history and a particular love of the work of the Historical Association records. Among staff, Jan most Join the Transcription Project! Society, “ she said recently. “I frequently responds to research-by-mail requests, searching the archives to answer questions from In the archives there are numerous congregational record count it a privilege to be on the people who are not in a position to do on-site books dating from the late-17th- to early-20th-centuries. -

Billy Graham: a New Kind of Evangelist

Monday, Oct. 25, 1954 Billy Graham: A New Kind of Evangelist The first one to come forward was a round, sensible-looking housewife with thick glasses. She stood as still and undramatic as if she were waiting to be served at the meat counter. The next was an eleven-year-old boy who kept his head low to hide his tears: a thin girl appeared behind him and put her arm comfortingly on his shoulder. These three were joined by a broad- shouldered young man whose machine-knitted jersey celebrated a leaping swordfish. then by a pretty young Negro woman in her best clothes with a sleeping baby in her arms. Suddenly there were too many to count, standing on the trampled grass in the blaze of lights. Some of them wept quietly, some of them stared at the ground and some looked upward. Above them all stood a tall, blond young man in a double-breasted tan gabardine suit. His handsome, strong-jawed face was drawn and his blue eyes glittered; for a few seconds he gnawed nervously on a thumbnail, and bright sweat covered his high forehead. He was speaking softly, but with an urgency that seemed to tense every muscle of his body: "You can leave here with peace and joy and happiness such as you've never known. You say: 'Well, 'Billy, that's all well and good. I'll think it over and I may come back some night and I'll—' Wait a minute! You can't come to Christ any time you want to. -

Creation/Evolution

Creation/Evolution Issue XXIV CONTENTS Fall 1988 ARTICLES 1 Formless and Void: Gap Theory Creationism by Tbm Mclver 25 Scientific Creationism: Adding Imagination to Scripture by Stanley Rice 37 Demographic Change and Antievolution Sentiment: Tennessee as a Case Study, 1925-1975 by George E. Webb FEATURES 43 Book Review 45 Letters to the Editor LICENSED TO UNZ.ORG ELECTRONIC REPRODUCTION PROHIBITED About this issue ... In this issue, Tom Mclver again brings his historical scholarship to bear on an issue relevant to creationism. This time, he explores the history of and the major players in the development and promotion of the "gap theory." Rarely do we treat in detail alternative creationist theories, preferring instead to focus upon the young- Earth special creationists who are so politically militant regarding public educa- tion. However, coverage of different creationist views is necessary from time to time in order to provide perspective and balance for those involved in the controversy. The second article compares scripture to the doctrines of young-Earth special crea- tionists and finds important disparities. Author Stanley Rice convincingly shows that "scientific" creationists add their own imaginative ideas in an effort to pseudoscientifically "flesh out" scripture. But why do so many people accept creationist notions? Some have maintained that the answer may be found through the study of demographics. George E. Webb explores that possibility in "Demographic Change and Antievolution Sentiment" and comes to some interesting conclusions. CREATION/EVOLUTION XXIV (Volume 8, Number 3} ISSN 0738-6001 Creation/Evolution, a publication dedicated to promoting evolutionary science, is published by the American Humanist Association. -

A New Protestantism Has Come": World War I, Premillennial Dispensationalism, and the Rise of Fundamentalism in Philadelphia

"A New Protestantism Has Come": World War I, Premillennial Dispensationalism, and the Rise of Fundamentalism in Philadelphia Richard Kent Evans Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies, Volume 84, Number 3, Summer 2017, pp. 292-312 (Article) Published by Penn State University Press For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/663963 Access provided by Temple University (19 Oct 2018 13:57 GMT) “a new protestantism has come” world war i, premillennial dispensationalism, and the rise of fundamentalism in philadelphia Richard Kent Evans Temple University abstract: This article interprets the rise of Protestant fundamentalism through the lens of an influential network of business leaders and theologians based in Philadelphia in the 1910s. This group of business and religious leaders, through insti- tutions such as the Philadelphia School of the Bible and a periodical called Serving and Waiting, popularized the apocalyptic theology of premillennial dispensationalism. As the world careened toward war, Philadelphia’s premillennial dispensational- ist movement grew more influential, reached a global audience, and cemented the theology’s place within American Christianity. However, when the war ended without the anticipated Rapture of believers, the money, politics, and organization behind Philadelphia’s dispensationalist movement collapsed, creating a vacuum that was filled by a new movement, fundamentalism. This article reveals the human politics behind the fall of dispensationalism, explores the movement’s rebranding as fundamentalism, and highlights Philadelphia’s central role in the rise of Protestant fundamentalism. keywords: Religion, fundamentalism, Philadelphia, theology, apocalypse On July 12, 1917, Blanche Magnin, along with twenty other members of the Africa Inland Mission, boarded the steamship City of Athens in New York and set sail for South Africa. -

William Bell Riley (1861-1947) ACCC 78Th Annual Convention, October 2019 Pastor Kevin Hobi 1. Annotated Bibliography. 1.1. Kevin

William Bell Riley (1861-1947) ACCC 78th Annual Convention, October 2019 Pastor Kevin Hobi 1. Annotated bibliography. 1.1. Kevin Bauder and Robert Delnay, One in Hope and Doctrine: Origins of Baptist Fundamentalism 1870-1950 (Schaumburg, IL: Regular Baptist Books, 2014). Authors provide a thorough treatment of the Baptist-fundamentalist ecclesiastical and historical context in which Riley ministered, including carefully researched detail about the interpersonal challenges involved in the co-labors among Baptist fundamentalist, including Riley. 1.2. David Beale, In Pursuit of Purity: American Fundamentalism Since 1850 (Greenville, SC: Unusual Publications, 1986). The author appreciates Riley’s contribution to multidenominational fundamentalism with a wider lens. Includes a chapter on Riley and one on the WCFA. He finds Riley’s lack of separatism enigmatic. 1.3. Marie Acomb Riley, The Dynamic of a Dream: The Life Story of Dr. William B. Riley (Grand Rapids, Michigan, 1938). The author is Riley’s second wife, and she provides a sympathetic biography with important details of Riley’s domestic background. 1.4. C. Allyn Russell, “William Bell Riley: Architect of Fundamentalism,” Minnesota History (Spring, 1972), 14-30. Author provides a fair historical summary of the many-faceted ministry of Riley. He appreciates Riley’s importance in regard to shaping American Protestantism. 1.5. Ferenc M. Szasz, “William B. Riley and the Fight Against Teaching of Evolution in Minnesota,” Minnesota History (Spring 1969), 201-216. The author provides enlightening details about Riley’s failed effort to see legislation passed in Minnesota that would prohibit the teaching of evolution in publicly funded schools in the 1920s.