HEROISM in the MATRIX: an Interpretation of Neo’S Heroism Through the Philosophies of Nietzsche and Chesterton

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Matrix As an Introduction to Mathematics

St. John Fisher College Fisher Digital Publications Mathematical and Computing Sciences Faculty/Staff Publications Mathematical and Computing Sciences 2012 What's in a Name? The Matrix as an Introduction to Mathematics Kris H. Green St. John Fisher College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/math_facpub Part of the Mathematics Commons How has open access to Fisher Digital Publications benefited ou?y Publication Information Green, Kris H. (2012). "What's in a Name? The Matrix as an Introduction to Mathematics." Mathematics in Popular Culture: Essays on Appearances in Film, Fiction, Games, Television and Other Media , 44-54. Please note that the Publication Information provides general citation information and may not be appropriate for your discipline. To receive help in creating a citation based on your discipline, please visit http://libguides.sjfc.edu/citations. This document is posted at https://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/math_facpub/18 and is brought to you for free and open access by Fisher Digital Publications at St. John Fisher College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. What's in a Name? The Matrix as an Introduction to Mathematics Abstract In my classes on the nature of scientific thought, I have often used the movie The Matrix (1999) to illustrate how evidence shapes the reality we perceive (or think we perceive). As a mathematician and self-confessed science fiction fan, I usually field questionselated r to the movie whenever the subject of linear algebra arises, since this field is the study of matrices and their properties. So it is natural to ask, why does the movie title reference a mathematical object? Of course, there are many possible explanations for this, each of which probably contributed a little to the naming decision. -

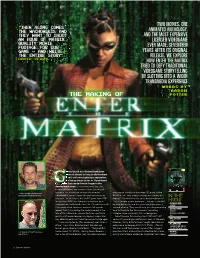

The Making of Enter the Matrix

TWO MOVIES. ONE “THEN ALONG COMES THE WACHOWSKIS AND ANIMATED ANTHOLOGY. THEY WANT TO SHOOT AND THE MOST EXPENSIVE AN HOUR OF MATRIX LICENSED VIDEOGAME QUALITY MOVIE FOOTAGE FOR OUR EVER MADE. SEVENTEEN GAME – AND WRITE YEARS AFTER ITS ORIGINAL THE ENTIRE STORY” RELEASE, WE EXPLORE DAVID PERRY HOW ENTER THE MATRIX TRIED TO DEFY TRADITIONAL VIDEOGAME STORYTELLING BY SLOTTING INTO A WIDER TRANSMEDIA EXPERIENCE Words by Aaron THE MAKING OF Potter ames based on a licence have been around almost as long as the medium itself, with most gaining a reputation for being cheap tie-ins or ill-produced cash grabs that needed much longer in the development oven. It’s an unfortunate fact that, in most instances, the creative teams tasked with » Shiny Entertainment founder and making a fun, interactive version of a beloved working on a really cutting-edge 3D game called former game director David Perry. Hollywood IP weren’t given the time necessary to Sacrifice, so I very embarrassingly passed on the IN THE succeed – to the extent that the ET game from 1982 project.” David chalks this up as being high on his for the Atari 2600 was famously rushed out by a “list of terrible career decisions”, though it wouldn’t KNOW single person and helped cause the US industry crash. be long before he and his team would be given a PUBLISHER: ATARI After every crash, however, comes a full system second chance. They could even use this pioneering DEVELOPER : reboot. And it was during the world’s reboot at the tech to translate the Wachowskis’ sprawling SHINY turn of the millennium, around the time a particular universe more accurately into a videogame. -

Report from Edinbur H • Soul Man Review • Robert Hooks Three Critics Look at She's Gotta Have It • Peter Wang Interview

Report From Edinbur h • Soul Man Review • Robert Hooks Three Critics Look at She's Gotta Have It • Peter Wang Interview World of Black Film Collectors Remembering Lorenzo Tucker- The Black. Gil Noble Plans Valentino Like It Is Archive Film Clips and News Early Black Independents Co-produced with the Black Film Institute of the University of the District of Columbia ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• Vol. 2, No. 4/Fa111986 'Peter Wang Breaks Cultural Barriers Black Film Review by Pat Aufderheide 10 SSt., NW An Interview with the director of A Great Wall p. 6 Washington, DC 20001 (202) 745-0455 Remembering lorenzo Tucker Editor and Publisher by Roy Campanella, II David Nicholson A personal reminiscence of one of the earliest stars of black film. ... p. 9 Consulting Editor Quick Takes From Edinburgh Tony Gittens by Clyde Taylor (Black Film Institute) Filmmakers debated an and aesthetics at the Edinburgh Festival p. 10 Associate EditorI Film Critic Anhur Johnson Film as a Force for Social Change Associate Editors by Charles Burnett Pat Aufderheide; Keith Boseman; Excerpts from a paper delivered at Edinburgh p. 12 Mark A. Reid; Saundra Sharp; A. Jacquie Taliaferro; Clyde Taylor Culture of Resistance Contributing Editors Excerpts from a paper p. 14 Bill Alexander; Carroll Parrott Special Section: Black Film History Blue; Roy Campanella, II; Darcy Collector's Dreams Demarco; Theresa furd; Karen by Saundra Sharp Jaehne; Phyllis Klotman; Paula Black film collectors seek to reclaim pieces of lost heritage p. 16 Matabane; Spencer Moon; An drew Szanton; Stan West. With a repon on effons to establish the Like It Is archive p. -

BEFORE the PHILOSOPHY There Are Several Ways That We Might Explain the Location of the Matrix

ONE BEFORE THE 7 PHILOSOPHY UNDERSTANDING THE FILMS BEFORE THE PHILOSOPHY I’m really struggling here. I’m trying to keep up, but I’m losing the plot. There is way too much weird shit going on around here and nothing is going the way it is supposed to go. I mean, doors that go nowhere and everywhere, programs acting like humans, multiplying agents . Oh when, when will it end? – SparksE The Matrix films often left audiences more confused than they had bargained for. Some say that their confusion began with the very first film, and was compounded with each sequel. Others understood the big picture, but found themselves a bit perplexed concerning the details. It’s safe to say that no one understands the films completely – there are always deeper levels to consider. So before we explore the more philosophical aspects of the films, I hope to clarify some of the common points of confusion. But first, I strongly encourage you to watch all three films. There are spoilers ahead. The Matrix Dreamworld You mean this isn’t real? – Neo† The Matrix is essentially a computer-generated dreamworld. It is the illusion of a world that no longer exists – a world of human technology and culture as it was at the end of the twentieth century. This illusion is pumped into the brains of millions of people who, in reality, are lying fast asleep in slime-filled cocoons. To them this virtual world seems like real life. They go to work, watch their televisions, and pay their taxes, fully believing that they are physically doing these things, when in fact they are doing them “virtually” – within their own minds. -

Facing the Absurd Existentialism for Humans and Programs

TWELVE 150 FACING THE ABSURD EXISTENTIALISM FOR HUMANS AND PROGRAMS The Matrix cannot tell you who you are. – Trinity†† Man is nothing else but what he makes of himself. Such is the first principle of existentialism. – Jean-Paul Sartre FACING THE ABSURD Of Gods and Architects Søren Kierkegaard, whose existentialist philosophy of faith was discussed in the previous chapter, requested that just two words be engraved on his tombstone at his death: THE INDIVIDUAL. This gesture nicely summarizes the main thrust of the existentialist movement in philosophy – which both begins and ends with the individual. Existentialism focuses on the issues that arise for us as separate and distinct persons who are, in a very profound sense, alone in the world. Its emphasis is on personal responsibility – on taking responsibility for who you are, what you do, and the meanings that you give to the world around you. While Kierkegaard’s existentialism was largely inspired by his religious commit- ments, atheism was the guiding assumption for many existentialist writers, includ- ing Martin Heidegger, Albert Camus, and Jean-Paul Sartre. In Existentialism as a Humanism, the French existentialist Jean-Paul Sartre explained how his philo- sophy was intimately tied to his atheism through the example of a paper-cutter. [H]ere is an object which has been made by an artisan whose inspiration came from a concept. He referred to the concept of what a paper-cutter is and likewise to a known method of production, which is part of the concept, something which by and large is a routine. Thus, the paper-cutter is at once an object produced in a certain way and, on the other hand, one having a specific use . -

The Matrix Trilogy's Postmodern Movie Messiah

Journal of Religion & Film Volume 9 Issue 2 October 2005 Article 7 October 2005 He is the One: The Matrix Trilogy's Postmodern Movie Messiah Mark D. Stucky [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf Recommended Citation Stucky, Mark D. (2005) "He is the One: The Matrix Trilogy's Postmodern Movie Messiah," Journal of Religion & Film: Vol. 9 : Iss. 2 , Article 7. Available at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol9/iss2/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Religion & Film by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. He is the One: The Matrix Trilogy's Postmodern Movie Messiah Abstract Many films have used Christ figures to enrich their stories. In The Matrix trilogy, however, the Christ figure motif goes beyond superficial plot enhancements and forms the fundamental core of the three-part story. Neo's messianic growth (in self-awareness and power) and his eventual bringing of peace and salvation to humanity form the essential plot of the trilogy. Without the messianic imagery, there could still be a story about the human struggle in the Matrix, of course, but it would be a radically different story than that presented on the screen. This article is available in Journal of Religion & Film: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol9/iss2/7 Stucky: He is the One Introduction The Matrix1 was a firepower-fueled film that spin-kicked filmmaking and popular culture. -

Starlog Magazine

THE MATRIX SCIENCE FICTION FILMS*TV*VIDEO Indiana Carrie-Anne 4 Jones' wild iss & the death JANUARY #318 r women * of Trinity Exploit terrain to gain tactical advantages. 'Welcome to Middle-earth* The journey begins this fall. OFFICIAL GAME BASED OS ''HE I.l'l't'.RAKY WORKS Of J.R.R. 'I'OI.KIKN www.lordoftherings.com * f> Sunita ft* NUMBER 318 • JANUARY 2004 THE SCIENCE FICTION UNIVERSE ^^^^ INSIDEiRicinE THISti 111* ISSUEicri ir 23 NEIL CAIMAN'S DREAMS The fantasist weaves new tales of endless nights 28 RICHARD DONNER SPEAKS i v iu tuuay jfck--- 32 FLIGHT OF THE FIREFLY Creator is \ 1 *-^J^ Joss Whedon glad to see his saga out on DVD 36 INDY'S WOMEN L/UUUy ICLdll IMC dLLIUII 40 GALACTICA 2.0 Ron Moore defends his plans for the brand-new Battlestar 46 THE WARRIOR KING Heroic Viggo Mortensen fights to save Middle-Earth 50 FRODO LIVES Atop Mount Doom, Elijah Wood faces a final test 54 OF GOOD FELLOWSHIP Merry turns grim as Dominic Monaghan joins the Riders 58 THAT SEXY CYLON! Tricia Heifer is the model of mocmodern mini-series menace 62 LANDniun OFAC THETUE BEARDEAD Disney's new animated film is a Native-American fantasy 66 BEING & ELFISHNESS Launch into space As a young man, Will Ferrell warfare with the was raised by Elves—no, SCI Fl Channel's new really Battlestar Galactica (see page 40 & 58). 71 KEYMAKER UNLOCKED! Does Randall Duk Kim hold the key to the Matrix mysteries? 74 78 PAINTING CYBERWORLDS Production designer Paterson STARLOC: The Science Fiction Universe is published monthly by STARLOG GROUP, INC., Owen 475 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10016. -

Breaking the Code of the Matrix; Or, Hacking Hollywood

Matrix.mss-1 September 1, 2002 “Breaking the Code of The Matrix ; or, Hacking Hollywood to Liberate Film” William B. Warner© Amusing Ourselves to Death The human body is recumbent, eyes are shut, arms and legs are extended and limp, and this body is attached to an intricate technological apparatus. This image regularly recurs in the Wachowski brother’s 1999 film The Matrix : as when we see humanity arrayed in the numberless “pods” of the power plant; as when we see Neo’s muscles being rebuilt in the infirmary; when the crew members of the Nebuchadnezzar go into their chairs to receive the shunt that allows them to enter the Construct or the Matrix. At the film’s end, Neo’s success is marked by the moment when he awakens from his recumbent posture to kiss Trinity back. The recurrence of the image of the recumbent body gives it iconic force. But what does it mean? Within this film, the passivity of the recumbent body is a consequence of network architecture: in order to jack humans into the Matrix, the “neural interactive simulation” built by the machines to resemble the “world at the end of the 20 th century”, the dross of the human body is left elsewhere, suspended in the cells of the vast power plant constructed by the machines, or back on the rebel hovercraft, the Nebuchadnezzar. The crude cable line inserted into the brains of the human enables the machines to realize the dream of “total cinema”—a 3-D reality utterly absorbing to those receiving the Matrix data feed.[footnote re Barzin] The difference between these recumbent bodies and the film viewers who sit in darkened theaters to enjoy The Matrix is one of degree; these bodies may be a figure for viewers subject to the all absorbing 24/7 entertainment system being dreamed by the media moguls. -

George P. Johnson Negro Film Collection LSC.1042

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf5s2006kz No online items George P. Johnson Negro Film Collection LSC.1042 Finding aid prepared by Hilda Bohem; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé UCLA Library Special Collections Online finding aid last updated on 2020 November 2. Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 [email protected] URL: https://www.library.ucla.edu/special-collections George P. Johnson Negro Film LSC.1042 1 Collection LSC.1042 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Title: George P. Johnson Negro Film collection Identifier/Call Number: LSC.1042 Physical Description: 35.5 Linear Feet(71 boxes) Date (inclusive): 1916-1977 Abstract: George Perry Johnson (1885-1977) was a writer, producer, and distributor for the Lincoln Motion Picture Company (1916-23). After the company closed, he established and ran the Pacific Coast News Bureau for the dissemination of Negro news of national importance (1923-27). He started the Negro in film collection about the time he started working for Lincoln. The collection consists of newspaper clippings, photographs, publicity material, posters, correspondence, and business records related to early Black film companies, Black films, films with Black casts, and Black musicians, sports figures and entertainers. Stored off-site. All requests to access special collections material must be made in advance using the request button located on this page. Language of Material: English . Conditions Governing Access Open for research. All requests to access special collections materials must be made in advance using the request button located on this page. Portions of this collection are available on microfilm (12 reels) in UCLA Library Special Collections. -

Read Book the Matrix

THE MATRIX PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Joshua Clover | 96 pages | 12 Jun 2007 | British Film Institute | 9781844570454 | English | London, United Kingdom The Matrix – Matrix Wiki – Neo, Trinity, the Wachowskis And the special effects are absolutely amazing even if similar ones have been used in other movies as a result- and not explained as well. But the movie has plot as well. It has characters that I cared about. From Keanu Reeves' excellent portrayal of Neo, the man trying to come to grips with his own identity, to Lawrence Fishburne's mysterious Morpheus, and even the creepy Agents, everyone does a stellar job of making their characters more than just the usual action "hero that kicks butt" and "cannon fodder" roles. I cared about each and every one of the heroes, and hated the villains with a passion. It has a plot, and it has a meaning Just try it, if you haven't seen the movie before. Watch one of the fight scenes. Then watch the whole movie. There's a big difference in the feeling and excitement of the scenes- sure, they're great as standalones, but the whole thing put together is an experience unlike just about everything else that's come to the theaters. Think about it next time you're watching one of the more brainless action flicks If you haven't, you're missing out on one of the best films of all time. It isn't just special effects, folks. Looking for some great streaming picks? Check out some of the IMDb editors' favorites movies and shows to round out your Watchlist. -

Matrix Reloaded Explained

Matrix Reloaded Explained Matrix Reloaded Explained The Matrix Explained 1 The Matrix: Reloaded Explained.........................................................................................................................1 1.1 Contents...................................................................................................................................................1 2 Forward on disobedience.......................................................................................................................................3 3 Foundation of criticism..........................................................................................................................................5 4 The Architect..........................................................................................................................................................7 5 The rave scene......................................................................................................................................................11 6 The Oracle.............................................................................................................................................................13 7 Agent Smith..........................................................................................................................................................15 8 Story arc................................................................................................................................................................19 -

UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Performing Recovery: Music and Disaster Relief in Post-3.11 Japan Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9jm4z24b Author Kaneko, Nana Publication Date 2017 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Performing Recovery: Music and Disaster Relief in Post-3.11 Japan A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music by Nana Kaneko June 2017 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Deborah Wong, Chairperson Dr. Margherita Long Dr. René T.A. Lysloff Dr. Jonathan Ritter Dr. Christina Schwenkel Copyright by Nana Kaneko 2017 The Dissertation of Nana Kaneko is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements It took an enormous crew of supporters to make my research possible. What follows is just a brief recognition of those who have generously contributed to this journey. Infinite gratitude goes to my advisor, Deborah Wong, who believed in me throughout my six years as a graduate student at UCR. Thank you for constantly challenging me to take my work to the next level, and for enthusiastically guiding me and getting me to the completion of this project. I hope this dissertation is at least a small reflection of the ways in which you have shaped me as a scholar, thinker, and researcher. To my committee members: Mimi Long, René Lysloff, Jonathan Ritter, and Christina Schwenkel, I had the privilege of taking seminars with each of you that inspired me deeply and prepared me to embark on my fieldwork and research.