The Matrix: Reloaded

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

See It Big! Action Features More Than 30 Action Movie Favorites on the Big

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE ‘SEE IT BIG! ACTION’ FEATURES MORE THAN 30 ACTION MOVIE FAVORITES ON THE BIG SCREEN April 19–July 7, 2019 Astoria, New York, April 16, 2019—Museum of the Moving Image presents See It Big! Action, a major screening series featuring more than 30 action films, from April 19 through July 7, 2019. Programmed by Curator of Film Eric Hynes and Reverse Shot editors Jeff Reichert and Michael Koresky, the series opens with cinematic swashbucklers and continues with movies from around the world featuring white- knuckle chase sequences and thrilling stuntwork. It highlights work from some of the form's greatest practitioners, including John Woo, Michael Mann, Steven Spielberg, Akira Kurosawa, Kathryn Bigelow, Jackie Chan, and much more. As the curators note, “In a sense, all movies are ’action’ movies; cinema is movement and light, after all. Since nearly the very beginning, spectacle and stunt work have been essential parts of the form. There is nothing quite like watching physical feats, pulse-pounding drama, and epic confrontations on a large screen alongside other astonished moviegoers. See It Big! Action offers up some of our favorites of the genre.” In all, 32 films will be shown, many of them in 35mm prints. Among the highlights are two classic Technicolor swashbucklers, Michael Curtiz’s The Adventures of Robin Hood and Jacques Tourneur’s Anne of the Indies (April 20); Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai (April 21); back-to-back screenings of Mad Max: Fury Road and Aliens on Mother’s Day (May 12); all six Mission: Impossible films -

Thematic, Moral and Ethical Connections Between the Matrix and Inception

Thematic, Moral and Ethical Connections Between the Matrix and Inception. Modern Day science and technology has been crucial in the development of the modern film industry. In the past, directors have been confined by unwieldy, primitive cameras and the most basic of special effects. The contemporary possibilities now available has enabled modern film to become more dynamic and versatile, whilst also being able to better capture the performance of actors, and better display scenes and settings using special effects. As the prevalence of technology in society increases, film makers have used their medium to express thematic, moral and ethical concerns of technology in human life. The films I will be looking at: The Matrix, directed by the Wachowskis, and Inception, directed by Christopher Nolan, both explore strong themes of technology. The theme of technology is expanded upon as the directors of both films explore the use of augmented reality and its effects on the human condition. Through the use of camera angles, costuming and lighting, the Witkowski brothers represent the idea that technology is dangerous. During the sequence where neo is unplugged from the Matrix, the directors have cleverly combines lighting, visual and special effects to craft an ominous and unpleasant setting in which the technology is present. Upon Neo’s confrontation with the spider drone, the use of camera angles to establishes the dominance of technology. The low-angle shot of the drone places the viewer in a subordinate position, making the drone appear powerful. The dingy lighting and poor mis-en-scene in the set further reinforces the idea that technology is dangerous. -

What's in a Name? the Matrix As an Introduction to Mathematics

St. John Fisher College Fisher Digital Publications Mathematical and Computing Sciences Faculty/Staff Publications Mathematical and Computing Sciences 9-2008 What's in a Name? The Matrix as an Introduction to Mathematics Kris H. Green St. John Fisher College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/math_facpub Part of the Mathematics Commons How has open access to Fisher Digital Publications benefited ou?y Publication Information Green, Kris H. (2008). "What's in a Name? The Matrix as an Introduction to Mathematics." Math Horizons 16.1, 18-21. Please note that the Publication Information provides general citation information and may not be appropriate for your discipline. To receive help in creating a citation based on your discipline, please visit http://libguides.sjfc.edu/citations. This document is posted at https://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/math_facpub/12 and is brought to you for free and open access by Fisher Digital Publications at St. John Fisher College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. What's in a Name? The Matrix as an Introduction to Mathematics Abstract In lieu of an abstract, here is the article's first paragraph: In my classes on the nature of scientific thought, I have often used the movie The Matrix to illustrate the nature of evidence and how it shapes the reality we perceive (or think we perceive). As a mathematician, I usually field questions elatedr to the movie whenever the subject of linear algebra arises, since this field is the study of matrices and their properties. So it is natural to ask, why does the movie title reference a mathematical object? Disciplines Mathematics Comments Article copyright 2008 by Math Horizons. -

The Matrix As an Introduction to Mathematics

St. John Fisher College Fisher Digital Publications Mathematical and Computing Sciences Faculty/Staff Publications Mathematical and Computing Sciences 2012 What's in a Name? The Matrix as an Introduction to Mathematics Kris H. Green St. John Fisher College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/math_facpub Part of the Mathematics Commons How has open access to Fisher Digital Publications benefited ou?y Publication Information Green, Kris H. (2012). "What's in a Name? The Matrix as an Introduction to Mathematics." Mathematics in Popular Culture: Essays on Appearances in Film, Fiction, Games, Television and Other Media , 44-54. Please note that the Publication Information provides general citation information and may not be appropriate for your discipline. To receive help in creating a citation based on your discipline, please visit http://libguides.sjfc.edu/citations. This document is posted at https://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/math_facpub/18 and is brought to you for free and open access by Fisher Digital Publications at St. John Fisher College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. What's in a Name? The Matrix as an Introduction to Mathematics Abstract In my classes on the nature of scientific thought, I have often used the movie The Matrix (1999) to illustrate how evidence shapes the reality we perceive (or think we perceive). As a mathematician and self-confessed science fiction fan, I usually field questionselated r to the movie whenever the subject of linear algebra arises, since this field is the study of matrices and their properties. So it is natural to ask, why does the movie title reference a mathematical object? Of course, there are many possible explanations for this, each of which probably contributed a little to the naming decision. -

Living in the Matrix: Virtual Reality Systems and Hyperspatial Representation in Architecture

Living in The Matrix: Virtual Reality Systems and Hyperspatial Representation in Architecture Kacmaz Erk, G. (2016). Living in The Matrix: Virtual Reality Systems and Hyperspatial Representation in Architecture. The International Journal of New Media, Technology and the Arts, 13-25. Published in: The International Journal of New Media, Technology and the Arts Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal Publisher rights © 2016 Gul Kacmaz Erk. Available under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The use of this material is permitted for non-commercial use provided the creator(s) and publisher receive attribution. No derivatives of this version are permitted. Official terms of this public license apply as indicated here: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. -

What Is the Link Between Religion, Myth and Plot in Any 2 Films of the Science Fiction Genre

Danielle Raffaele Robert A Dallen Prize Topic: A study of the influence of the Bible on the two contemporary science fiction films, The Matrix and Avatar, with a focus on the link between religion, myth and plot. The two films The Matrix (1999, the Wachowski brothers) and Avatar (2009, James Cameron)1 belong to the science fiction genre2 of the contemporary film world and each evoke a diverse set of religiosity and myth within their respective plots. The two films are rich with both overt and subvert religious imagery of motifs and symbolism which one can interpret as belonging to many diverse streams of religious thought and practice across the globe.3 For the purpose of this essay I will be focussing specifically on one religious mode of thought being a Judeo-Christian look at the role of the Messiah and its relation to the hero myth. I will develop this by exploring the archetype of the hero with the two different roles of the biblical Messiah (one being conqueror, and the other of 1 In this essay I presume the reader is familiar with the two films as I do not provide an extensive synopsis or summary of them. I recommend going to the Internet Movie Database (http://imdb.com) and searching for ‘The Matrix’ and ‘Avatar’ for a generous reading of the two plots. 2 Science fiction as a genre will not be discussed in this essay but a definition that struck me as useful for the purpose here is, “My own definition is that science fiction is literature about something that hasn’t happened yet, but might be possible some day. -

Christianity, Buddhism & Baudrillard in the Matrix Films and Popular Culture

Butler University Digital Commons @ Butler University Scholarship and Professional Work - LAS College of Liberal Arts & Sciences 2010 The Desert of the Real: Christianity, Buddhism & Baudrillard in The Matrix Films and Popular Culture James F. McGrath Butler University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/facsch_papers Part of the Philosophy Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation James F. McGrath. "The Desert of the Real: Christianity, Buddhism & Baudrillard in The Matrix Films and Popular Culture" Visions of the Human in Science Fiction and Cyberpunk. Ed. Marcus Leaning & Birgit Pretzsch. Oxford, UK: Inter-Disciplinary Press, 2010. 161-172. Available from: digitalcommons.butler.edu/ facsch_papers/556/ This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Liberal Arts & Sciences at Digital Commons @ Butler University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scholarship and Professional Work - LAS by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Butler University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Edited by Marcus Leaning & Birgit Pretzsch The Desert of the Real: Christianity, Buddhism & Baudrillard in The Matrix Films and Popular Culture James F. McGrath Abstract The movie The Matrix and its sequels draw explicitly on imagery from a number of sources, including in particular Buddhism, Christianity, and the writings of Jean Baudrillard. A perspective is offered on the perennial philosophical question ‘What is real?’, using language and symbols drawn from three seemingly incompatible world views. In doing so, these movies provide us with an insight into the way popular culture makes eclectic use of various streams of thought to fashion a new reality that is not unrelated to, and yet is nonetheless distinct from, its religious and philosophical undercurrents and underpinnings. -

Adam Sandler: Mentor Of

ADAM SANDLER: MENTOR OF MIDDLE-CLASS MASCULINITY AND MANHOOD A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, Stanislaus In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in History By Kathleen Boone Chapman April 2014 CERTIFICATION OF APPROVAL ADAM SANDLER: MENTOR OF MASCULINITY AND FATHERHOOD by Kathleen Boone Chapman Signed Certification of Approval Page is on file with the University Library Dr. Bret E. Carroll Date Professor of History Dr. Samuel Regalado Date Professor of History Dr. Marcy Rose Chvasta Date Professor of Communications © 2014 Kathleen Boone Chapman ALL RIGHTS RESERVED DEDICATION I am dedicating this work to my three dear friends: Ronda James, Candace Paulson, and Michele Sniegoski. Ronda’s encouragement and obedience to the Lord gave me what I needed to go back to school with significant health issues and so late in life. Candace, who graduated from Stanford “back in the olden days,” to quote our kids, inspired me to follow my dream and become all God wants me to be. Michele’s long struggle with terminal kidney disease motivated me to keep living in spite of my own health issues. We have laughed and cried together over many years, but all of you have given me strength to carry on. Sorry two of you made it to heaven before I could get this finished. I also want to give credit to my husband of forty years who has been a faithful breadwinner, proof-reader, and a paragon of patience. What more could any woman ask for? He has also put up with me yelling at my computer and cursing Bill Gates – A LOT. -

Theaters 3 & 4 the Grand Lodge on Peak 7

The Grand Lodge on Peak 7 Theaters 3 & 4 NOTE: 3D option is only available in theater 3 Note: Theater reservations are for 2 hours 45 minutes. Movie durations highlighted in Orange are 2 hours 20 minutes or more. Note: Movies with durations highlighted in red are only viewable during the 9PM start time, due to their excess length Title: Genre: Rating: Lead Actor: Director: Year: Type: Duration: (Mins.) The Avengers: Age of Ultron 3D Action PG-13 Robert Downey Jr. Joss Whedon 2015 3D 141 Born to be Wild 3D Family G Morgan Freeman David Lickley 2011 3D 40 Captain America : The Winter Soldier 3D Action PG-13 Chris Evans Anthony Russo/ Jay Russo 2014 3D 136 The Chronicles of Narnia: The Voyage of the Dawn Treader 3D Adventure PG Georgie Henley Michael Apted 2010 3D 113 Cirque Du Soleil: Worlds Away 3D Fantasy PG Erica Linz Andrew Adamson 2012 3D 91 Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs 2 3D Animation PG Ana Faris Cody Cameron 2013 3D 95 Despicable Me 3D Animation PG Steve Carell Pierre Coffin 2010 3D 95 Despicable Me 2 3D Animation PG Steve Carell Pierre Coffin 2013 3D 98 Finding Nemo 3D Animation G Ellen DeGeneres Andrew Stanton 2003 3D 100 Gravity 3D Drama PG-13 Sandra Bullock Alfonso Cuaron 2013 3D 91 Hercules 3D Action PG-13 Dwayne Johnson Brett Ratner 2014 3D 97 Hotel Transylvania Animation PG Adam Sandler Genndy Tartakovsky 2012 3D 91 Ice Age: Continetal Drift 3D Animation PG Ray Romano Steve Martino 2012 3D 88 I, Frankenstein 3D Action PG-13 Aaron Eckhart Stuart Beattie 2014 3D 92 Imax Under the Sea 3D Documentary G Jim Carrey Howard Hall -

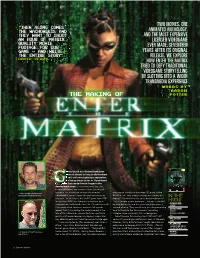

The Making of Enter the Matrix

TWO MOVIES. ONE “THEN ALONG COMES THE WACHOWSKIS AND ANIMATED ANTHOLOGY. THEY WANT TO SHOOT AND THE MOST EXPENSIVE AN HOUR OF MATRIX LICENSED VIDEOGAME QUALITY MOVIE FOOTAGE FOR OUR EVER MADE. SEVENTEEN GAME – AND WRITE YEARS AFTER ITS ORIGINAL THE ENTIRE STORY” RELEASE, WE EXPLORE DAVID PERRY HOW ENTER THE MATRIX TRIED TO DEFY TRADITIONAL VIDEOGAME STORYTELLING BY SLOTTING INTO A WIDER TRANSMEDIA EXPERIENCE Words by Aaron THE MAKING OF Potter ames based on a licence have been around almost as long as the medium itself, with most gaining a reputation for being cheap tie-ins or ill-produced cash grabs that needed much longer in the development oven. It’s an unfortunate fact that, in most instances, the creative teams tasked with » Shiny Entertainment founder and making a fun, interactive version of a beloved working on a really cutting-edge 3D game called former game director David Perry. Hollywood IP weren’t given the time necessary to Sacrifice, so I very embarrassingly passed on the IN THE succeed – to the extent that the ET game from 1982 project.” David chalks this up as being high on his for the Atari 2600 was famously rushed out by a “list of terrible career decisions”, though it wouldn’t KNOW single person and helped cause the US industry crash. be long before he and his team would be given a PUBLISHER: ATARI After every crash, however, comes a full system second chance. They could even use this pioneering DEVELOPER : reboot. And it was during the world’s reboot at the tech to translate the Wachowskis’ sprawling SHINY turn of the millennium, around the time a particular universe more accurately into a videogame. -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 90Th Academy Awards Alien

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 90TH ACADEMY AWARDS ALIEN: COVENANT Actors: Michael Fassbender. Billy Crudup. Danny McBride. Demian Bichir. Jussie Smollett. Nathaniel Dean. Alexander England. Benjamin Rigby. Uli Latukefu. Goran D. Kleut. Actresses: Katherine Waterston. Carmen Ejogo. Callie Hernandez. Amy Seimetz. Tess Haubrich. Lorelei King. ALL I SEE IS YOU Actors: Jason Clarke. Wes Chatham. Danny Huston. Actresses: Blake Lively. Ahna O'Reilly. Yvonne Strahovski. ALL THE MONEY IN THE WORLD Actors: Christopher Plummer. Mark Wahlberg. Romain Duris. Timothy Hutton. Charlie Plummer. Charlie Shotwell. Andrew Buchan. Marco Leonardi. Giuseppe Bonifati. Nicolas Vaporidis. Actresses: Michelle Williams. ALL THESE SLEEPLESS NIGHTS AMERICAN ASSASSIN Actors: Dylan O'Brien. Michael Keaton. David Suchet. Navid Negahban. Scott Adkins. Taylor Kitsch. Actresses: Sanaa Lathan. Shiva Negar. AMERICAN MADE Actors: Tom Cruise. Domhnall Gleeson. Actresses: Sarah Wright. AND THE WINNER ISN'T ANNABELLE: CREATION Actors: Anthony LaPaglia. Brad Greenquist. Mark Bramhall. Joseph Bishara. Adam Bartley. Brian Howe. Ward Horton. Fred Tatasciore. Actresses: Stephanie Sigman. Talitha Bateman. Lulu Wilson. Miranda Otto. Grace Fulton. Philippa Coulthard. Samara Lee. Tayler Buck. Lou Lou Safran. Alicia Vela-Bailey. ARCHITECTS OF DENIAL ATOMIC BLONDE Actors: James McAvoy. John Goodman. Til Schweiger. Eddie Marsan. Toby Jones. Actresses: Charlize Theron. Sofia Boutella. 90th Academy Awards Page 1 of 34 AZIMUTH Actors: Sammy Sheik. Yiftach Klein. Actresses: Naama Preis. Samar Qupty. BPM (BEATS PER MINUTE) Actors: 1DKXHO 3«UH] %LVFD\DUW $UQDXG 9DORLV $QWRLQH 5HLQDUW] )«OL[ 0DULWDXG 0«GKL 7RXU« Actresses: $GªOH +DHQHO THE B-SIDE: ELSA DORFMAN'S PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHY BABY DRIVER Actors: Ansel Elgort. Kevin Spacey. Jon Bernthal. Jon Hamm. Jamie Foxx. -

22Nd Anniversary of the MATRIX: Fans Highlight Interesting Information from This Trilogy

22nd Anniversary of THE MATRIX: fans highlight interesting information from this trilogy The successful Matrix trilogy will be available on HBO Max beginning on June 29thThe sci-fi trilogy, which premiered in 1999, describes a future in which the reality perceived by human beings is the matrix, a simulated reality created by machines in order to pacify the human population. Here is some of the information collected by fans that perhaps you did not know:The Bullet Time Effect was used for the first time in cinema. It is a filming technique that allows you to film specific action scenes in 360 degrees and play them back in slow-motion. Its premiere was so successful that at the time it became Warner Bros’ biggest hit to date (1999). It was the first film in the world to sell 1 million DVDs. Some of the actors that were considered for parts in the project were: Sandra Bullock, Brad Pitt and Leonardo DiCaprio Keanu Reeves decided to share his earnings with the entire team that took part in filming the movie, such as makeup, sound, lighting, etc. The recognizable code that appears on screens when the Matrix is encoded is a Japanese sushi recipe. The shooting scene in the lobby of the building where the Agents are holding Morpheus took 10 days to film. Ironically, the name Morpheus comes from Greek mythology and means God of sleep, which contradicts his role in the film. The movie was filmed in Australia although the names of the streets in the film come from Chicago.