OJIOS1990019004003.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Biodiversity Work Group Report: Appendices

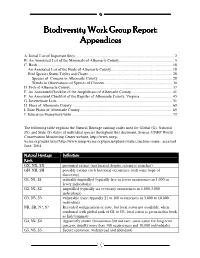

Biodiversity Work Group Report: Appendices A: Initial List of Important Sites..................................................................................................... 2 B: An Annotated List of the Mammals of Albemarle County........................................................ 5 C: Birds ......................................................................................................................................... 18 An Annotated List of the Birds of Albemarle County.............................................................. 18 Bird Species Status Tables and Charts...................................................................................... 28 Species of Concern in Albemarle County............................................................................ 28 Trends in Observations of Species of Concern..................................................................... 30 D. Fish of Albemarle County........................................................................................................ 37 E. An Annotated Checklist of the Amphibians of Albemarle County.......................................... 41 F. An Annotated Checklist of the Reptiles of Albemarle County, Virginia................................. 45 G. Invertebrate Lists...................................................................................................................... 51 H. Flora of Albemarle County ...................................................................................................... 69 I. Rare -

![[The Pond\. Odonatoptera (Odonata)]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4965/the-pond-odonatoptera-odonata-114965.webp)

[The Pond\. Odonatoptera (Odonata)]

Odonatological Abstracts 1987 1993 (15761) SAIKI, M.K. &T.P. LOWE, 1987. Selenium (15763) ARNOLD, A., 1993. Die Libellen (Odonata) in aquatic organisms from subsurface agricultur- der “Papitzer Lehmlachen” im NSG Luppeaue bei al drainagewater, San JoaquinValley, California. Leipzig. Verbff. NaturkMus. Leipzig 11; 27-34. - Archs emir. Contam. Toxicol. 16: 657-670. — (US (Zur schonen Aussicht 25, D-04435 Schkeuditz). Fish & Wildl. Serv., Natn. Fisheries Contaminant The locality is situated 10km NW of the city centre Res. Cent., Field Res, Stn, 6924 Tremont Rd, Dixon, of Leipzig, E Germany (alt, 97 m). An annotated CA 95620, USA). list is presented of 30 spp., evidenced during 1985- Concentrations of total selenium were investigated -1993. in plant and animal samplesfrom Kesterson Reser- voir, receiving agricultural drainage water (Merced (15764) BEKUZIN, A.A., 1993. Otryad Strekozy - — Co.) and, as a reference, from the Volta Wildlife Odonatoptera(Odonata). [OrderDragonflies — km of which Area, ca 10 S Kesterson, has high qual- Odonatoptera(Odonata)].Insectsof Uzbekistan , pp. ity irrigationwater. Overall,selenium concentrations 19-22,Fan, Tashkent, (Russ.). - (Author’s address in samples from Kesterson averaged about 100-fold unknown). than those from Volta. in and A rather 20 of higher Thus, May general text, mentioning (out 76) spp. Aug. 1983, the concentrations (pg/g dry weight) at No locality data, but some notes on their habitats Kesterson in larval had of 160- and vertical in Central Asia. Zygoptera a range occurrence 220 and in Anisoptera 50-160. In Volta,these values were 1.2-2.I and 1.1-2.5, respectively. In compari- (15765) GAO, Zhaoning, 1993. -

Data-Driven Identification of Potential Zika Virus Vectors Michelle V Evans1,2*, Tad a Dallas1,3, Barbara a Han4, Courtney C Murdock1,2,5,6,7,8, John M Drake1,2,8

RESEARCH ARTICLE Data-driven identification of potential Zika virus vectors Michelle V Evans1,2*, Tad A Dallas1,3, Barbara A Han4, Courtney C Murdock1,2,5,6,7,8, John M Drake1,2,8 1Odum School of Ecology, University of Georgia, Athens, United States; 2Center for the Ecology of Infectious Diseases, University of Georgia, Athens, United States; 3Department of Environmental Science and Policy, University of California-Davis, Davis, United States; 4Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies, Millbrook, United States; 5Department of Infectious Disease, University of Georgia, Athens, United States; 6Center for Tropical Emerging Global Diseases, University of Georgia, Athens, United States; 7Center for Vaccines and Immunology, University of Georgia, Athens, United States; 8River Basin Center, University of Georgia, Athens, United States Abstract Zika is an emerging virus whose rapid spread is of great public health concern. Knowledge about transmission remains incomplete, especially concerning potential transmission in geographic areas in which it has not yet been introduced. To identify unknown vectors of Zika, we developed a data-driven model linking vector species and the Zika virus via vector-virus trait combinations that confer a propensity toward associations in an ecological network connecting flaviviruses and their mosquito vectors. Our model predicts that thirty-five species may be able to transmit the virus, seven of which are found in the continental United States, including Culex quinquefasciatus and Cx. pipiens. We suggest that empirical studies prioritize these species to confirm predictions of vector competence, enabling the correct identification of populations at risk for transmission within the United States. *For correspondence: mvevans@ DOI: 10.7554/eLife.22053.001 uga.edu Competing interests: The authors declare that no competing interests exist. -

Biology and Control of Aquatic Plants

BIOLOGY AND CONTROL OF AQUATIC PLANTS A Best Management Practices Handbook Lyn A. Gettys, William T. Haller and Marc Bellaud, editors Cover photograph courtesy of SePRO Corporation Biology and Control of Aquatic Plants: A Best Management Practices Handbook First published in the United States of America in 2009 by Aquatic Ecosystem Restoration Foundation, Marietta, Georgia ISBN 978-0-615-32646-7 All text and images used with permission and © AERF 2009 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, by photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. Printed in Gainesville, Florida, USA October 2009 Dear Reader: Thank you for your interest in aquatic plant management. The Aquatic Ecosystem Restoration Foundation (AERF) is pleased to bring you Biology and Control of Aquatic Plants: A Best Management Practices Handbook. The mission of the AERF, a not for profit foundation, is to support research and development which provides strategies and techniques for the environmentally and scientifically sound management, conservation and restoration of aquatic ecosystems. One of the ways the Foundation accomplishes the mission is by providing information to the public on the benefits of conserving aquatic ecosystems. The handbook has been one of the most successful ways of distributing information to the public regarding aquatic plant management. The first edition of this handbook became one of the most widely read and used references in the aquatic plant management community. This second edition has been specifically designed with the water resource manager, water management association, homeowners and customers and operators of aquatic plant management companies and districts in mind. -

A Review of the Mosquito Species (Diptera: Culicidae) of Bangladesh Seth R

Irish et al. Parasites & Vectors (2016) 9:559 DOI 10.1186/s13071-016-1848-z RESEARCH Open Access A review of the mosquito species (Diptera: Culicidae) of Bangladesh Seth R. Irish1*, Hasan Mohammad Al-Amin2, Mohammad Shafiul Alam2 and Ralph E. Harbach3 Abstract Background: Diseases caused by mosquito-borne pathogens remain an important source of morbidity and mortality in Bangladesh. To better control the vectors that transmit the agents of disease, and hence the diseases they cause, and to appreciate the diversity of the family Culicidae, it is important to have an up-to-date list of the species present in the country. Original records were collected from a literature review to compile a list of the species recorded in Bangladesh. Results: Records for 123 species were collected, although some species had only a single record. This is an increase of ten species over the most recent complete list, compiled nearly 30 years ago. Collection records of three additional species are included here: Anopheles pseudowillmori, Armigeres malayi and Mimomyia luzonensis. Conclusions: While this work constitutes the most complete list of mosquito species collected in Bangladesh, further work is needed to refine this list and understand the distributions of those species within the country. Improved morphological and molecular methods of identification will allow the refinement of this list in years to come. Keywords: Species list, Mosquitoes, Bangladesh, Culicidae Background separation of Pakistan and India in 1947, Aslamkhan [11] Several diseases in Bangladesh are caused by mosquito- published checklists for mosquito species, indicating which borne pathogens. Malaria remains an important cause of were found in East Pakistan (Bangladesh). -

A Checklist of North American Odonata

A Checklist of North American Odonata Including English Name, Etymology, Type Locality, and Distribution Dennis R. Paulson and Sidney W. Dunkle 2009 Edition (updated 14 April 2009) A Checklist of North American Odonata Including English Name, Etymology, Type Locality, and Distribution 2009 Edition (updated 14 April 2009) Dennis R. Paulson1 and Sidney W. Dunkle2 Originally published as Occasional Paper No. 56, Slater Museum of Natural History, University of Puget Sound, June 1999; completely revised March 2009. Copyright © 2009 Dennis R. Paulson and Sidney W. Dunkle 2009 edition published by Jim Johnson Cover photo: Tramea carolina (Carolina Saddlebags), Cabin Lake, Aiken Co., South Carolina, 13 May 2008, Dennis Paulson. 1 1724 NE 98 Street, Seattle, WA 98115 2 8030 Lakeside Parkway, Apt. 8208, Tucson, AZ 85730 ABSTRACT The checklist includes all 457 species of North American Odonata considered valid at this time. For each species the original citation, English name, type locality, etymology of both scientific and English names, and approxi- mate distribution are given. Literature citations for original descriptions of all species are given in the appended list of references. INTRODUCTION Before the first edition of this checklist there was no re- Table 1. The families of North American Odonata, cent checklist of North American Odonata. Muttkows- with number of species. ki (1910) and Needham and Heywood (1929) are long out of date. The Zygoptera and Anisoptera were cov- Family Genera Species ered by Westfall and May (2006) and Needham, West- fall, and May (2000), respectively, but some changes Calopterygidae 2 8 in nomenclature have been made subsequently. Davies Lestidae 2 19 and Tobin (1984, 1985) listed the world odonate fauna Coenagrionidae 15 103 but did not include type localities or details of distri- Platystictidae 1 1 bution. -

A List of the Odonata of Honduras Sidney W

A list of the Odonata of Honduras Sidney W. Dunkle* SUMMARY. The 147 species of dragonflies and damsel- fliesknownfrom Honduras are usted, along with their distribution by political department. Of these records, 54 are new for Honduras, including 9 which extend known ranges of species northward or southward. RESUMEN. Las 147 especies de libélulas conocidas en Honduras son mencionados junto con su distribución por depar- tamento. De esta cifra, 54 especies son nuevas en Honduras. Nueve especies han ampliado sus límites geográficos llegando a este país por el sur y por el norte. Very little has been written about the Odonata of Hondu- ras. Williamson (1905) gave some notes on collecting in Cortes De- partment, mostly near San Pedro Sula, but did not ñame the species taken. Williamson (1923b) briefly discussed the habitat of 4 species of Hetaerina collected near San Pedro Sula. Paulson (1982) in his table of Odonata occurrences in Central American countrieslisted 94 species íromHondur as. ArgiadifficilisSe\y$ has been deleted from the Honduran list because it is thought not to occur in Central America, and was confused with A. oculata Hagen (R. W. Garrison, pers. comm.). The list below includes 54 more species for a total of 147. Of the new records, 5 extend the known ranges of species southward and 4 extend ranges northward. Paulson (1982) listed 54 other species which occur both north and south of Honuras, and therefore can be expected in that country. While the records of Odonata givenhere are of interestfor purely scientific reasons, they should also be of interest as base line * Entomology and Nematology Department, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida, 32611. -

Sinaloa, Mexico, Although Nayarit (GONZALEZ 1901-08). Only Specimens from Nayarit (BELLE, (GONZALEZ SORIANO Aphylla Protracta

Odonatologica 31(4): 359-370 December 1, 2002 Odonatarecords from Nayaritand Sinaloa, Mexico, with comments on natural history and biogeography D.R. Paulson SlaterMuseum ofNatural History, University ofPuget Sound, Tacoma, WA 98416, United States e-mail: [email protected] Received February 28, 2002 / Revised and Accepted April 4, 2002 Although the odon. fauna of the Mexican state of Nayarit has been considered well- for -known, a 7-day visit there in Sept. 2001 resulted in records of 21 spp. new the state, the state total to 120 fifth in Mexico, Records visit in bringing spp., highest from a 2-day 1965 Aug. are also listed, many of them the first specific localities published forNayarit, andthe first records of 2 from Sinaloa spp. are also listed. The biology ofmost neotropical is notes included A spp. poorly known, sonatural-history are for many spp, storm-induced of described. aggregation and a large roost dragonflies is The odon. fauna of Nayarit consists of 2 elements: a number of their primary large neotropical spp. reaching northern known At least limits, and a montane fauna of the drier Mexican Plateau. 57 spp. of tropical origin reach their northern distribution in the western Mexican lowlands in orN of Nayarit, and these limits must be more accurately defined to detect the changes in distribution that be with climate may taking place global change. INTRODUCTION Although Nayarit has been considereda “well-known”Mexican state (GONZALEZ SORIANO & NOVELO GUTIERREZ, 1996),almost the entire published recordfrom the state consists of records from the 19th century (CALVERT, 1899, 1901-08). Only a few subsequent papers have mentioned specimens from Nayarit (BELLE, 1987; BORROR, 1942; CANNINGS & GARRISON, 1991; COOK & GONZALEZ SORIANO, 1990;DONNELLY, 1979;GARRISON, 1994a, 1994b; PAULSON, 1994, and each ofthem 1998), has listed only a record or two from the state. -

A Checklist of North American Odonata, 2021 1 Each Species Entry in the Checklist Is a Paragraph In- Table 2

A Checklist of North American Odonata Including English Name, Etymology, Type Locality, and Distribution Dennis R. Paulson and Sidney W. Dunkle 2021 Edition (updated 12 February 2021) A Checklist of North American Odonata Including English Name, Etymology, Type Locality, and Distribution 2021 Edition (updated 12 February 2021) Dennis R. Paulson1 and Sidney W. Dunkle2 Originally published as Occasional Paper No. 56, Slater Museum of Natural History, University of Puget Sound, June 1999; completely revised March 2009; updated February 2011, February 2012, October 2016, November 2018, and February 2021. Copyright © 2021 Dennis R. Paulson and Sidney W. Dunkle 2009, 2011, 2012, 2016, 2018, and 2021 editions published by Jim Johnson Cover photo: Male Calopteryx aequabilis, River Jewelwing, from Crab Creek, Grant County, Washington, 27 May 2020. Photo by Netta Smith. 1 1724 NE 98th Street, Seattle, WA 98115 2 8030 Lakeside Parkway, Apt. 8208, Tucson, AZ 85730 ABSTRACT The checklist includes all 471 species of North American Odonata (Canada and the continental United States) considered valid at this time. For each species the original citation, English name, type locality, etymology of both scientific and English names, and approximate distribution are given. Literature citations for original descriptions of all species are given in the appended list of references. INTRODUCTION We publish this as the most comprehensive checklist Table 1. The families of North American Odonata, of all of the North American Odonata. Muttkowski with number of species. (1910) and Needham and Heywood (1929) are long out of date. The Anisoptera and Zygoptera were cov- Family Genera Species ered by Needham, Westfall, and May (2014) and West- fall and May (2006), respectively. -

Odonata De Puerto Rico

Odonata de Puerto Rico Libellulidae Foto Especie Notas Brachymesia furcata http://america-dragonfly.net/ Brachymesia herbida http://america-dragonfly.net/ Crocothemis servilia http://kn-naturethai.blogspot.com/2011/01/crocothemis- servilia-servilia.html Dythemis rufinervis http://www.mangoverde.com/dragonflies/ picpages/pic160-85-2.html Erythemis plebeja http://america-dragonfly.net/ Erythemis vesiculosa http://america-dragonfly.net/ Erythrodiplax berenice http://america-dragonfly.net/ Erythrodiplax fervida http://america-dragonfly.net/ Erythrodiplax justiniana http://www.martinreid.com/Odonata%20website/ odonatePR12.html Erythrodiplax umbrata http://america-dragonfly.net/ Idiataphe cubensis Tórax metálico. http://bugguide.net/node/view/501418/bgpage Macrothemis celeno http://odonata.lifedesks.org/pages/15910 Miathyria marcella http://america-dragonfly.net/ Miathyria simplex http://america-dragonfly.net/ Micrathyria aequalis http://america-dragonfly.net/ Micrathyria didyma http://america-dragonfly.net/ Micrathyria dissocians http://america-dragonfly.net/ Micrathyria hageni http://america-dragonfly.net/ Orthemis macrostigma http://america-dragonfly.net/ Pantala flavescens http://america-dragonfly.net/ Pantala hymenaea http://america-dragonfly.net/ Perithemis domitia http://america-dragonfly.net/ Scapanea frontalis http://www.catsclem.nl/dieren/insectenm.htm Paulson Tauriphila australis http://www.wildphoto.nl/peru/libellulidae2.html Tholymis citrina http://america-dragonfly.net/ Tramea abdominalis http://america-dragonfly.net/ Tramea binotata http://america-dragonfly.net/ Tramea calverti http://america-dragonfly.net/ Tramea insularis www.thehibbitts.net Tramea onusta http://america-dragonfly.net/ . -

The Proventriculus of Immature Anisoptera (Odonata) with Reference to Its Use in Taxonomy

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1955 The rP oventriculus of Immature Anisoptera (Odonata) With Reference to Itsuse in Taxonomy. Alice Howard Ferguson Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Ferguson, Alice Howard, "The rP oventriculus of Immature Anisoptera (Odonata) With Reference to Itsuse in Taxonomy." (1955). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 103. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/103 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE PROTENTRICULUS OF IMMATURE ANISOPTERA (ODONATA) WITH REFERENCE TO ITS USE IN TAXONOMY A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Zoology, Physiology, and Entomology Alice Howard Ferguson B. S., Southern Methodist University, 193& M. S., Southern Methodist University, I9U0 June, 1955 EXAMINATION AND THESIS REPORT Candidate: Miss Alice Ferguson Major Field: Entomology Title of Thesis: The Proventriculus of Immature Anisoptera (Odonata) with Reference to its Use in Taxonomy Approved: Major Professor and Chairman Deanpf-tfio Graduate School EXAMINING COMMITTEE: m 1.1 ^ ----------------------------- jJ------- --- 7 ------ Date of Examination: May6 , 195$ PiKC t U R D C N ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I want to express ny appreciation to the members of ny committee, especially to J. -

Cumulative Index of ARGIA and Bulletin of American Odonatology

Cumulative Index of ARGIA and Bulletin of American Odonatology Compiled by Jim Johnson PDF available at http://odonata.bogfoot.net/docs/Argia-BAO_Cumulative_Index.pdf Last updated: 14 February 2021 Below are titles from all issues of ARGIA and Bulletin of American Odonatology (BAO) published to date by the Dragonfly Society of the Americas. The purpose of this listing is to facilitate the searching of authors and title keywords across all issues in both journals, and to make browsing of the titles more convenient. PDFs of ARGIA and BAO can be downloaded from https://www.dragonflysocietyamericas.org/en/publications. The most recent three years of issues for both publications are only available to current members of the Dragonfly Society of the Americas. Contact Jim Johnson at [email protected] if you find any errors. ARGIA 1 (1–4), 1989 Welcome to the Dragonfly Society of America Cook, C. 1 Society's Name Revised Cook, C. 2 DSA Receives Grant from SIO Cook, C. 2 North and Central American Catalogue of Odonata—A Proposal Donnelly, T.W. 3 US Endangered Species—A Request for Information Donnelly, T.W. 4 Odonate Collecting in the Peruvian Amazon Dunkle, S.W. 5 Collecting in Costa Rica Dunkle, S.W. 6 Research in Progress Garrison, R.W. 8 Season Summary Project Cook, C. 9 Membership List 10 Survey of Ohio Odonata Planned Glotzhober, R.C. 11 Book Review: The Dragonflies of Europe Cook, C. 12 Book Review: Dragonflies of the Florida Peninsula, Bermuda and the Bahamas Cook, C. 12 Constitution of the Dragonfly Society of America 13 Exchanges and Notices 15 General Information About the Dragonfly Society of America (DSA) Cook, C.