Fire and Rain: Stemming the Tide of Invasive Plants in Hawaiian Ecosystems

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Story About Understory Why Everyone on Bald Head Island Should Care

Bald Head Association 910-457-4676 • www.BaldHeadAssociation.com 111 Lighthouse Wynd • PO Box 3030, Bald Head Island, NC 28461 The Story About Understory Why Everyone on Bald Head Island Should Care Bald Head Island is truly unique. As a barrier island, it at ground level. Bald Head Island’s latitudinal position is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean and Cape Fear River. BHI has supports both northern and southern species of plants.” 14 miles of pristine beaches; 12,400 acres, of which 10,000 acres Important understory plants include vines, small plants and are protected; over 244 species of birds, including the bald eagle; trees, mosses, lichens and even weeds. All are needed to have and the North Carolina Forest Preserve of nearly 200 acres. a healthy forest habitat. Many extreme forces of nature that have helped shape this The BHIC explains, “Vines play an important role. The very special island include hurricane-force winds, salt water and vines and herbaceous plants intertwine, further developing the salt spray, flooding and drought. There is another force of nature structural integrity of the forest and forming pockets of vegetation that impacts BHI — humans — and with us, development. that provide a base for songbirds to build nests. The vines twist The Bald Head Association is mandated by its Covenants to around the canopy and are the secret to wind protection. These help sustain BHI by managing the buildout of homes and by vines actually weave together the canopy so blowing winds don’t managing vegetation trimming/removal, to help protect its penetrate through the top layer and keep homes, plants, and members’ property values. -

Metrosideros Polymorpha Gaudich

Metrosideros polymorpha Gaudich. JAMES A. ALLEN Paul Smiths College, Paul Smiths, NY MYRTACEAE (MYRTLE FAMILY) Metrosideros collina (J.R. and G. Forst.) A. Gray subsp. polymorpha (Gaud.) Rock. (Little and Skolmen 1989). See also the extensive list of synonyms in Wagner and others (1990) Lehua, ‘ohi’a Metrosideros is a genus of about 50 species. With the excep- hybridization and genetic polymorphism is unknown (Wagner tion of one species found in South Africa, all grow in the and others 1990). Pacific from the Philippines, through Papua New Guinea, to The heartwood is reddish brown, heavy (specific gravity New Zealand and on high volcanic islands (Wagner and oth- of about 0.70), of fine and even texture, very hard, and strong. ers 1990). Five species occur in the Hawaiian Islands (Wag- Native Hawaiians used the wood extensively for construction, ner and others 1990). Metrosideros polymorpha is native to household implements, and carvings. Principal modern uses Hawaii, where it grows on all the main islands except Niihau include flooring, marine construction, pallets, fenceposts, and and Kahoolawe. It is the most abundant and widespread fuelwood. The wood’s limitations include excessive shrinkage M native tree in Hawaii (Adee and Conrad 1990) and grows in in drying, density, and the difficulty and expense of harvesting association with numerous species in both wet and relatively in low-volume stands (Adee and Conrad 1990, Little and Skol- dry forests. men 1989). Today, M. polymorpha is perhaps most highly val- Metrosideros polymorpha is a slow-growing, evergreen ued in Hawaii for uses in watershed protection, aesthetics, and species capable of reaching 24 to 30 m in height and about 1 m habitat for native birds, including several endangered species. -

Old-Growth Forests

Pacific Northwest Research Station NEW FINDINGS ABOUT OLD-GROWTH FORESTS I N S U M M A R Y ot all forests with old trees are scientifically defined for many centuries. Today’s old-growth forests developed as old growth. Among those that are, the variations along multiple pathways with many low-severity and some Nare so striking that multiple definitions of old-growth high-severity disturbances along the way. And, scientists forests are needed, even when the discussion is restricted to are learning, the journey matters—old-growth ecosystems Pacific coast old-growth forests from southwestern Oregon contribute to ecological diversity through every stage of to southwestern British Columbia. forest development. Heterogeneity in the pathways to old- growth forests accounts for many of the differences among Scientists understand the basic structural features of old- old-growth forests. growth forests and have learned much about habitat use of forests by spotted owls and other species. Less known, Complexity does not mean chaos or a lack of pattern. Sci- however, are the character and development of the live and entists from the Pacific Northwest (PNW) Research Station, dead trees and other plants. We are learning much about along with scientists and students from universities, see the structural complexity of these forests and how it leads to some common elements and themes in the many pathways. ecological complexity—which makes possible their famous The new findings suggest we may need to change our strat- biodiversity. For example, we are gaining new insights into egies for conserving and restoring old-growth ecosystems. canopy complexity in old-growth forests. -

Keauhou Bird Conservation Center

KEAUHOU BIRD CONSERVATION CENTER Discovery Forest Restoration Project PO Box 2037 Kamuela, HI 96743 Tel +1 808 776 9900 Fax +1 808 776 9901 Responsible Forester: Nicholas Koch [email protected] +1 808 319 2372 (direct) Table of Contents 1. CLIENT AND PROPERTY INFORMATION .................................................................... 4 1.1. Client ................................................................................................................................................ 4 1.2. Consultant ....................................................................................................................................... 4 2. Executive Summary .................................................................................................. 5 3. Introduction ............................................................................................................. 6 3.1. Site description ............................................................................................................................... 6 3.1.1. Parcel and location .................................................................................................................. 6 3.1.2. Site History ................................................................................................................................ 6 3.2. Plant ecosystems ............................................................................................................................ 6 3.2.1. Hydrology ................................................................................................................................ -

Understory Forest Monitoring: a Guide for Small Forest Managers

Understory Forest Monitoring: A Guide for Small Forest Managers With funding provided by BEFORE: A dense monoculture of invasive periwinkle (Vinca species). AFTER: A diverse mix of native vegetation beginning to establish. It will mature into a lush forest Á oor of native wildÁ owers. Managing a healthy forest is not just about having healthy trees. Foresters, scientists, and private woodland owners have an interest in what is growing on the forest Á oor. A healthy understory can offer: • Flowers for native pollinators • Food for wildlife • Resiliency against invasion by forest weeds • Organic material to build healthier soil • Stable soil that doesn’t erode into nearby streams • Beautiful views while recreating in the forest Just like taking inventory of the forest, measuring tree diameters and spacing, it is also important to monitor the changes over time on the forest Á oor. Herbaceous forest plants tend to reach their peak bloom and cover in mid to late spring (mid-May to mid-June in western Oregon). It’s best to monitor forest understory consistently at this time of year. There are dozens of ways to monitor the understory plants in a forest. Two effective methods are described here. Point intercept method This method is performed by laying out a straight line transect in the forest and documenting what is growing on the forest Á oor at one- foot increments along the transect. West Multnomah Soil & Water Conservation District often sets up multiple transects that are 33’ in length giving us 33 data points per transect. The data gathered from the plots can be used to À nd the average cover of different vegetation types in your forest. -

Accelerating the Development of Old-Growth Characteristics in Second-Growth Northern Hardwoods

United States Department of Agriculture Accelerating the Development of Old-growth Characteristics in Second-growth Northern Hardwoods Karin S. Fassnacht, Dustin R. Bronson, Brian J. Palik, Anthony W. D’Amato, Craig G. Lorimer, Karl J. Martin Forest Northern General Technical Service Research Station Report NRS-144 February 2015 Abstract Active management techniques that emulate natural forest disturbance and stand development processes have the potential to enhance species diversity, structural complexity, and spatial heterogeneity in managed forests, helping to meet goals related to biodiversity, ecosystem health, and forest resilience in the face of uncertain future conditions. There are a number of steps to complete before, during, and after deciding to use active management for this purpose. These steps include specifying objectives and identifying initial targets, recognizing and addressing contemporary stressors that may hinder the ability to meet those objectives and targets, conducting a pretreatment evaluation, developing and implementing treatments, and evaluating treatments for success of implementation and for effectiveness after application. In this report we discuss these steps as they may be applied to second-growth northern hardwood forests in the northern Lake States region, using our experience with the ongoing managed old-growth silvicultural study (MOSS) as an example. We provide additional examples from other applicable studies across the region. Quality Assurance This publication conforms to the Northern Research Station’s Quality Assurance Implementation Plan which requires technical and policy review for all scientific publications produced or funded by the Station. The process included a blind technical review by at least two reviewers, who were selected by the Assistant Director for Research and unknown to the author. -

Apapane (Himatione Sanguinea)

The Birds of North America, No. 296, 1997 STEVEN G. FANCY AND C. JOHN RALPH 'Apapane Himatione sanguinea he 'Apapane is the most abundant species of Hawaiian honeycreeper and is perhaps best known for its wide- ranging flights in search of localized blooms of ō'hi'a (Metrosideros polymorpha) flowers, its primary food source. 'Apapane are common in mesic and wet forests above 1,000 m elevation on the islands of Hawai'i, Maui, and Kaua'i; locally common at higher elevations on O'ahu; and rare or absent on Lāna'i and Moloka'i. density may exceed 3,000 birds/km2 The 'Apapane and the 'I'iwi (Vestiaria at times of 'ōhi'a flowering, among coccinea) are the only two species of Hawaiian the highest for a noncolonial honeycreeper in which the same subspecies species. Birds in breeding condition occurs on more than one island, although may be found in any month of the historically this is also true of the now very rare year, but peak breeding occurs 'Ō'ū (Psittirostra psittacea). The highest densities February through June. Pairs of 'Apapane are found in forests dominated by remain together during the breeding 'ōhi'a and above the distribution of mosquitoes, season and defend a small area which transmit avian malaria and avian pox to around the nest, but most 'Apapane native birds. The widespread movements of the 'Apapane in response to the seasonal and patchy distribution of ' ōhi'a The flowering have important implications for disease Birds of transmission, since the North 'Apapane is a primary carrier of avian malaria and America avian pox in Hawai'i. -

E666134Z Enhance Development of the Forest Understory to Create

CONSERVATION ENHANCEMENT ACTIVITY E666134Z Enhance development of the forest understory to create conditions resistant to pests Conservation Practice 666: Forest Stand Improvement APPLICABLE LAND USE: Forest RESOURCE CONCERN ADDRESSED: Degraded Plant Condition PRACTICE LIFE SPAN: 10 Years Enhancement Description: Forest stand improvement that manages the structure and composition of overstory and understory vegetation to reduce vulnerability to damage by insects and diseases of forest trees. Managing the understory vegetation will also reduce the risk of wildfire, and promote development of herbaceous plants that benefit wildlife. This enhancement provides for management of the understory vegetation in a forested area, using mechanical, chemical or manual methods to improve the plant species mix and the health of the residual vegetation. These practices encourage the development of a less dense forested ecosystem. The canopy gaps and open understory allow for air circulation that reduces the incidence of disease, and the improved health of the residual trees increases their ability to withstand insect attacks. Forest stand improvement (FSI) activities are used to remove trees of undesirable species, form, quality, condition, or growth rate. The quantity and quality of forest for wildlife and/or timber production will be increased by manipulating stand density and structure. These treatments can also reduce wildfire hazards, improve forest health, restore natural plant communities, and achieve or maintain a desired native understory plant community for soil health, wildlife, grazing, and/or browsing. Criteria: States will apply general criteria from the NRCS National Conservation Practice Standard (CPS) 666 as listed below, and additional criteria as required by the NRCS State Office. The enhancement will be applied to sites which have an uncharacteristically dense understory of shrubs and small trees that limit development of ground cover. -

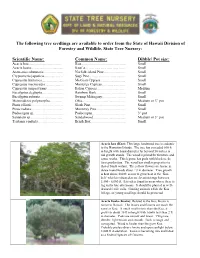

The Following Tree Seedlings Are Available to Order from the State of Hawaii Division of Forestry and Wildlife, State Tree Nursery

The following tree seedlings are available to order from the State of Hawaii Division of Forestry and Wildlife, State Tree Nursery: Scientific Name: Common Name: Dibble/ Pot size: Acacia koa……………………… Koa……………………………….. Small Acacia koaia……………………... Koai’a……………………………. Small Araucaria columnaris…………….. Norfolk-island Pine……………… Small Cryptomeria japonica……………. Sugi Pine………………………… Small Cupressus lusitanica……………... Mexican Cypress………………… Small Cupressus macrocarpa…………… Monterey Cypress……………….. Small Cupressus simpervirens………….. Italian Cypress…………………… Medium Eucalyptus deglupta……………… Rainbow Bark……………………. Small Eucalyptus robusta……………….. Swamp Mahogany……………….. Small Metrosideros polymorpha……….. Ohia……………………………… Medium or 3” pot Pinus elliotii……………………… Slash Pine………………………... Small Pinus radiata……………………... Monterey Pine…………………… Small Podocarpus sp……………………. Podocarpus………………………. 3” pot Santalum sp……………………… Sandalwood……………………… Medium or 3” pot Tristania conferta………………… Brush Box………………………... Small Acacia koa (Koa): This large hardwood tree is endemic to the Hawaiian Islands. The tree has exceeded 100 ft in height with basal diameter far beyond 50 inches in old growth stands. The wood is prized for furniture and canoe works. This legume has pods with black seeds for reproduction. The wood has similar properties to that of black walnut. The yellow flowers are borne in dense round heads about 2@ in diameter. Tree growth is best above 800 ft; seems to grow best in the ‘Koa belt’ which is situated at an elevation range between 3,500 - 6,000 ft. It is often found in areas where there is fog in the late afternoons. It should be planted in well- drained fertile soils. Grazing animals relish the Koa foliage, so young seedlings should be protected Acacia koaia (Koaia): Related to the Koa, Koaia is native to Hawaii. The leaves and flowers are much the same as Koa. -

Achatinella Abbreviata (O`Ahu Tree Snail) 5-Year Review Summary And

Achatinella abbreviata (O`ahu Tree Snail) 5-Year Review Summary and Evaluation U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Pacific Islands Fish and Wildlife Office Honolulu, Hawai`i 5-YEAR REVIEW Species reviewed: Achatinella abbreviata (O`ahu tree snail) TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 GENERAL INFORMATION.......................................................................................... 3 1.1 Reviewers....................................................................................................................... 3 1.2 Methodology used to complete the review:................................................................. 3 1.3 Background: .................................................................................................................. 3 2.0 REVIEW ANALYSIS....................................................................................................... 4 2.1 Application of the 1996 Distinct Population Segment (DPS) policy......................... 4 2.2 Recovery Criteria.......................................................................................................... 5 2.3 Updated Information and Current Species Status .................................................... 6 2.4 Synthesis......................................................................................................................... 9 3.0 RESULTS ........................................................................................................................ 10 3.1 Recommended Classification:................................................................................... -

Forest Biomes DAY ONE Biomes Section 2

Biomes Section 2 Chapter 6: Biomes Section 2: Forest Biomes DAY ONE Biomes Section 2 Forest Biomes • Of all the biomes in the world, forest biomes are the most widespread and the most diverse. • The large trees of forests need a lot of water, so forests can be found where temperatures are mild to hot and where rainfall is plenty. • There are three main forest biomes of the world: tropical, temperate, and coniferous. Biomes Section 2 Tropical Rainforests • Tropical rain forests are forests or jungles near the equator. • They are characterized by large amounts of rain and little variation in temperature and contain the greatest known diversity of organisms on Earth. • They help regulate world climate an play vital roles in the nitrogen, oxygen, and carbon cycles. • They are humid, warm, and get strong sunlight which allows them to maintain a fairly constant temperature that is ideal for a wide variety of plants and animals. Biomes Section 2 Tropical Rainforests Biomes Section 2 Nutrients in Tropical Rainforests • Most nutrients are within the plants, not the soil. • Decomposers on the rainforest floor break down dead organisms and return the nutrients to the soil, but plants quickly absorb the nutrients. • Some trees in the tropical rain forest support fungi that feed on dead organic matter on the rainforest floor. • In this relationship, the fungi transfer the nutrients from the dead matter directly to the tree. Biomes Section 2 Nutrients in Tropical Rainforests • Nutrients from dead organic matter are removed so efficiently that runoff from rain forests is often as pure as distilled water. -

The Threat of the Non-Native Neotropical Rust Puccinia Psidii to Hawaiian Biodiversity and Native Ecosystems: a Case Example of the Need for Prevention

The Threat of the Non-native Neotropical Rust Puccinia psidii to Hawaiian Biodiversity and Native Ecosystems: A Case Example of the Need for Prevention Lloyd Loope, U.S. Geological Survey,Pacific Island Ecosystems Research Center, Haleaka- la Field Station, P.O. Box 369, Makawao, HI 96768; [email protected] Janice Uchida, Department of Plant and Environmental Protection Sciences, University of Hawaii at Manoa, 3190 Maile Way, Honolulu, HI 96822; [email protected] Loyal Mehrhoff, U.S. Geological Survey, Pacific Island Ecosystems Research Center, 677 Ala Moana Boulevard, Suite 615, Honolulu, HI 96813; [email protected] Introduction The threat of invasive species to natural areas presents enormous challenges, but there are opportunities for working toward solutions, often in conjunction with agricultural and forestry perspectives. There is a growing awareness of the danger to botanical biodiversity and conservation from “emerging infectious diseases” that have increased in incidence, geo- graphical distribution, or host range/pathogenicity; have newly evolved characteristics; and/or have been newly discovered (Anderson et al. 2004). There is a heightened concern for forest health due to accelerating worldwide movement of plant pathogens (e.g., with inef- fective quarantine measures) that negatively affect both biodiversity and commercial forestry (Wingfield 2003). An important related concept is that of the ability of fungi to jump to new hosts following anthropogenic introduction. Native hosts are exposed to pathogens with no coevolved recognition or defense mechanism, and microevolution toward increased viru- lence of introduced pathogens can result (Wingfield 2003; Slippers et al. 2005). The rust fungus Puccinia psidii (Basidiomycota, Uredinales: Pucciniaceae), a species first document- ed to have jumped from native guava (Psidium guajava, Myrtaceae) to introduced Eucalyp- tus spp.