Hawaiian Hoary Bat Inventory in National Parks on Hawaii, Maui and Molokai

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pacific Sheath-Tailed Bat American Samoa Emballonura Semicaudata Semicaudata Species Report April 2020

Pacific Sheath-tailed Bat American Samoa Emballonura semicaudata semicaudata Species Report April 2020 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Pacific Islands Fish and Wildlife Office Honolulu, HI Cover Photo Credits Shawn Thomas, Bat Conservation International. Suggested Citation USFWS. 2020. Species Status Assessment for the Pacific Sheath Tailed Bat (Emballonura semicaudata semicaudata). April 2020 (Version 1.1). U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Pacific Islands Fish and Wildlife Office, Honolulu, HI. 57 pp. Primary Authors Version 1.1 of this document was prepared by Mari Reeves, Fred Amidon, and James Kwon of the Pacific Islands Fish and Wildlife Office, Honolulu, Hawaii. Preparation and review was conducted by Gregory Koob, Megan Laut, and Stephen E. Miller of the Pacific Islands Fish and Wildlife Office. Acknowledgements We thank the following individuals for their contribution to this work: Marcos Gorresen, Adam Miles, Jorge Palmeirim, Dave Waldien, Dick Watling, and Gary Wiles. ii Executive Summary This Species Report uses the best available scientific and commercial information to assess the status of the semicaudata subspecies of the Pacific sheath-tailed bat, Emballonura semicaudata semicaudata. This subspecies is found in southern Polynesia, eastern Melanesia, and Micronesia. Three additional subspecies of E. semicaudata (E.s. rotensis, E.s. palauensis, and E.s. sulcata) are not discussed here unless they are used to support assumptions about E.s. semicaudata, or to fill in data gaps in this analysis. The Pacific sheath-tailed bat is an Old-World bat in the family Emballonuridae, and is found in parts of Polynesia, eastern Melanesia, and Micronesia. It is the only insectivorous bat recorded from much of this area. -

Iucn Bat Specialist Group Newsletter

IUCN BAT SPECIALIST GROUP NEWSLETTER ISSUE 1 NOVEMBER 2014 CHALLENGES IN BAT CONSERVATION: A WORLDWIDE PERSPECTIVE Dear Readers, It is a pleasure to introduce the first issue of the IUCN Bat Specialist Group Newsletter. Our aim is to inform the BSG community about the status and major threats of bats, as well as conservation and policy efforts to recover and maintain bat populations around the world. We hope you enjoy the reading, Maria Sagot, Editor of the IUCN Bat Specialist Group Newsletter BSG EDITORIAL BOARD BSG CO-CHAIRS LATIN AMERICA AND THE Prof. Dr. Paul Racey CARIBBEAN University of Exeter in Cornwall Bs. Luis R. Víquez Rodríguez Cornwall, England Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Email: [email protected] México México DF, México Prof. Dr. Rodrigo Medellín Email: [email protected] Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México NORTH AMERICA México DF, México Prof. Dr. Winifred Frick Email: [email protected] University of California Santa Cruz x California, United States Email: [email protected] WEB MASTER Dr. Allyson Walsh OCEANIA San Diego ZOO California, United States Dr. Colin O’Donnell Email: [email protected] New Zealand Department of Conservation Wellington, New Zealand Email: [email protected] EDITOR IN-CHIEF Prof. Dr. Maria Sagot SOUTHEAST ASIA State University of New York at Oswego New York, United States Prof. Dr. Faisal Ali Anwarali Email: [email protected] Khan Universiti Malaysia Sarawak AFRICA Sarawak, Malaysia Email: [email protected] Ms. Iroro Tanshi University of Benin Benin, Nigeria Email: [email protected] EUROPE Ms. Daniela Hamidović State Institute for Nature Protection Zagreb, Croatia Email: [email protected] Cover Photos: Colin O’Donell, Tigga Kingston and Iroro Tanshi. -

Metrosideros Polymorpha Gaudich

Metrosideros polymorpha Gaudich. JAMES A. ALLEN Paul Smiths College, Paul Smiths, NY MYRTACEAE (MYRTLE FAMILY) Metrosideros collina (J.R. and G. Forst.) A. Gray subsp. polymorpha (Gaud.) Rock. (Little and Skolmen 1989). See also the extensive list of synonyms in Wagner and others (1990) Lehua, ‘ohi’a Metrosideros is a genus of about 50 species. With the excep- hybridization and genetic polymorphism is unknown (Wagner tion of one species found in South Africa, all grow in the and others 1990). Pacific from the Philippines, through Papua New Guinea, to The heartwood is reddish brown, heavy (specific gravity New Zealand and on high volcanic islands (Wagner and oth- of about 0.70), of fine and even texture, very hard, and strong. ers 1990). Five species occur in the Hawaiian Islands (Wag- Native Hawaiians used the wood extensively for construction, ner and others 1990). Metrosideros polymorpha is native to household implements, and carvings. Principal modern uses Hawaii, where it grows on all the main islands except Niihau include flooring, marine construction, pallets, fenceposts, and and Kahoolawe. It is the most abundant and widespread fuelwood. The wood’s limitations include excessive shrinkage M native tree in Hawaii (Adee and Conrad 1990) and grows in in drying, density, and the difficulty and expense of harvesting association with numerous species in both wet and relatively in low-volume stands (Adee and Conrad 1990, Little and Skol- dry forests. men 1989). Today, M. polymorpha is perhaps most highly val- Metrosideros polymorpha is a slow-growing, evergreen ued in Hawaii for uses in watershed protection, aesthetics, and species capable of reaching 24 to 30 m in height and about 1 m habitat for native birds, including several endangered species. -

Main Hawaiian Islands Monk Seal Management Plan December 2015 Main Hawaiian Islands Monk Seal Management Plan

Pacific Islands Region Main Hawaiian Islands Monk Seal Management Plan December 2015 Main Hawaiian Islands Monk Seal Management Plan NOAA Fisheries Pacific Islands Regional Office December 2015 Lead Author: Rachel S. Sprague, Ph.D. Contributing Authors: Jeffrey S. Walters, Ph.D., Benjamin Baron-Taltre, Nicole Davis Recommended Citation: National Marine Fisheries Service. 2015. DRAFT Main Hawaiian Islands Monk Seal Management Plan. National Marine Fisheries Service, Pacific Islands Region, Honolulu, HI. Acknowledgements This plan is the result of wide public participation in planning meetings, technical workshops, focus groups, and other meetings. We would like to thank the Monk Seal Foundation for facilitating stakeholder and community involvement in the development of this plan by hosting a workshop in September 2012 and several focus groups in June 2014. In addition, focus groups with native Hawaiians were facilitated by Honua Consulting in 2012. NOAA Fisheries appreciates the participants’ involvement in developing and reviewing early drafts of the plan, and sharing their valuable expertise and knowledge to make this a participatory plan. NOAA Fisheries gratefully acknowledges the following people who contributed by writing sections or reviewing drafts of the plan (in alphabetical order): Angela Amlin, Jason Baker, Michelle Barbieri, Malia Chow, Therese Conant, Nicole Davis, Ann Garrett, Elia Herman, Charles Littnan, Kimberly Maison, Earl Miyamoto, Stacie Robinson, David Schofield, Jamie Thomton, Lisa Van Atta, Lisa White, Tracy Wurth, and Nancy Young. The Hawaiian Monk Seal Recovery Team provided substantial valuable comments and input: Phil Fernandez, Cal Hirai, David Hyrenbach, Sabra Kauka, Julie Leilaloha, Lloyd Lowry, Kepa Maly, Dane Maxwell, Tim Ragen (chair), Walter Ritte, Craig Severance, and Darrell Tanaka. -

Featured Resource Hawaiian Hoary Bat — 'Ope'ape'a

Pacific Island Network — Featured Resource Hawaiian Hoary Bat — 'Ope'ape'a Description: The Hawaiian hoary bat (La- in order to complete a monitoring protocol accurate knowledge of distribution, relative siurus cinereus semotus) is the only terrestrial in 2007. Monitoring objectives will focus on abundance, and habitat needs will be required. mammal native to Hawaii . Ancient Hawaiians assessing presence and distribution of bats in called this solitary and elusive bat 'Ope'ape'a, the Hawaiian National Parks, relative levels of Management: Due to limited and conflict- as its wings reminded them of the half-leaf bat activity and occurrence, and general habitat ing information regarding Hawaiian hoary bats, remaining on a taro stalk after the top half has associations. critical habitat for this subspecies has not yet been removed for cooking. Although pres- been designated. As a result, even the most ba- ent in Hawaii for many centuries, the earliest Data: The 'Ope'ape'a has been documented sic management strategies are difficult to imple- recorded sighting was December 8, 1816, when in NPSpecies for most of Hawaii’s National ment. Threats to this species remain unclear, one was shot near Pearl Harbor, O'ahu. It is Parks. A Hawaiian hoary bat recovery plan but habitat loss, pesticide use, predation, and believed the Hawaiian hoary bat is a relative of was developed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife roost disturbance are primary concerns. Fu- the North American hoary bat, which originally Service, which seeks to downlist this species ture research is needed to identify and protect migrated at least 2000 miles from the mainland. -

Hawaiian Hoary Bat Guidance Document Draft

Hawaiian Hoary Bat Guidance for Renewable Wind Energy Proponents Endangered Species Recovery Committee and State of Hawaii Department of Land and Natural Resources Division of Forestry and Wildlife Updated January 2020 (First edition September 2015) Cover Photo by Corinna Pinzari 2020 Hawaiian Hoary Bat Guidance Document Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................................ 4 A. Purpose ............................................................................................................................................ 4 B. Need ................................................................................................................................................. 6 C. Process .............................................................................................................................................. 7 II. Background ......................................................................................................................................... 8 A. Ecology and Status of the Hawaiian Hoary Bat ......................................................................... 8 B. Bats and Wind Energy ................................................................................................................... 8 C. Hawaiian Hoary Bats and Wind Energy in Hawai‘i ................................................................. 9 III. Assessment of Take and Impacts for HCPs ............................................................................. -

SB775 RELATING to STATE LAND MAMMAL. Hawaiian Hoary Bat; State Land Mammal

From: S?D. Sam Sjom To: TCCTe5tirnony Subject: FW: S6 77S LATE Date: Thursday, February 21, 2013 8:50:17 AM Attachments: 58775 SUPPQrt-doC' From: Myron Berney [mailto:[email protected]] Sent: Tuesday, February 12, 2013 10:20 AM To: Sen. Sam Slam Subject: SB 77S Dr. Myron Berney SB775 RELATING TO STATE LAND MAMMAL. Hawaiian Hoary Bat; State Land Mammal Support In 1970, the Hawaiian hoary bat was listed as an endangered species. Hoary Bats eat mosquitoes and other bugs. The State of Hawaii generally opposes the introduction of alien species, even lady bugs from the mainland, because they have the potential to upset the existing balance and possibly eat an important pollinator for Hawaii's native species. The Hoary Bat is Local and part of the Native Hawaiian Ecological System Awareness and Protection of the Hoary Bat is essential for the Public Health and Agriculture. Vector control is essential for decreasing the spread of mosquito and bug born illness. Hawaii Tourist economy had been adversely impacted with Public Health Fears due to mosquito born illness. Most common has been the West Nile Virus although recently there has been concern with Malaria. Pandemics are a major world wide pubic health issue. The bird flu transfer to humans is expected to be through mosquitoes. The Hoary Bat is also helpful in controlling agricultural pests. htip·lIeo.wikioedia,prg{wjki/Hawaiian hoary bat Dr. Myron Berney SB775 RELATING TO STATE LAND MAMMAL. Hawaiian Hoary Bat; State Land Mammal Support In 1970, the Hawaiian hoary bat was listed as an endangered species. -

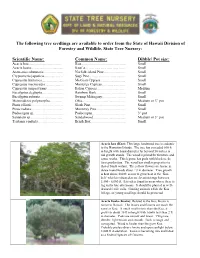

The Following Tree Seedlings Are Available to Order from the State of Hawaii Division of Forestry and Wildlife, State Tree Nursery

The following tree seedlings are available to order from the State of Hawaii Division of Forestry and Wildlife, State Tree Nursery: Scientific Name: Common Name: Dibble/ Pot size: Acacia koa……………………… Koa……………………………….. Small Acacia koaia……………………... Koai’a……………………………. Small Araucaria columnaris…………….. Norfolk-island Pine……………… Small Cryptomeria japonica……………. Sugi Pine………………………… Small Cupressus lusitanica……………... Mexican Cypress………………… Small Cupressus macrocarpa…………… Monterey Cypress……………….. Small Cupressus simpervirens………….. Italian Cypress…………………… Medium Eucalyptus deglupta……………… Rainbow Bark……………………. Small Eucalyptus robusta……………….. Swamp Mahogany……………….. Small Metrosideros polymorpha……….. Ohia……………………………… Medium or 3” pot Pinus elliotii……………………… Slash Pine………………………... Small Pinus radiata……………………... Monterey Pine…………………… Small Podocarpus sp……………………. Podocarpus………………………. 3” pot Santalum sp……………………… Sandalwood……………………… Medium or 3” pot Tristania conferta………………… Brush Box………………………... Small Acacia koa (Koa): This large hardwood tree is endemic to the Hawaiian Islands. The tree has exceeded 100 ft in height with basal diameter far beyond 50 inches in old growth stands. The wood is prized for furniture and canoe works. This legume has pods with black seeds for reproduction. The wood has similar properties to that of black walnut. The yellow flowers are borne in dense round heads about 2@ in diameter. Tree growth is best above 800 ft; seems to grow best in the ‘Koa belt’ which is situated at an elevation range between 3,500 - 6,000 ft. It is often found in areas where there is fog in the late afternoons. It should be planted in well- drained fertile soils. Grazing animals relish the Koa foliage, so young seedlings should be protected Acacia koaia (Koaia): Related to the Koa, Koaia is native to Hawaii. The leaves and flowers are much the same as Koa. -

Achatinella Abbreviata (O`Ahu Tree Snail) 5-Year Review Summary And

Achatinella abbreviata (O`ahu Tree Snail) 5-Year Review Summary and Evaluation U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Pacific Islands Fish and Wildlife Office Honolulu, Hawai`i 5-YEAR REVIEW Species reviewed: Achatinella abbreviata (O`ahu tree snail) TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 GENERAL INFORMATION.......................................................................................... 3 1.1 Reviewers....................................................................................................................... 3 1.2 Methodology used to complete the review:................................................................. 3 1.3 Background: .................................................................................................................. 3 2.0 REVIEW ANALYSIS....................................................................................................... 4 2.1 Application of the 1996 Distinct Population Segment (DPS) policy......................... 4 2.2 Recovery Criteria.......................................................................................................... 5 2.3 Updated Information and Current Species Status .................................................... 6 2.4 Synthesis......................................................................................................................... 9 3.0 RESULTS ........................................................................................................................ 10 3.1 Recommended Classification:................................................................................... -

Rain Forest Relationships

Rain Forest Unit 2 Rain Forest Relationships Overview Length of Entire Unit In this unit, students learn about some of the Five class periods main species in the rain forests of Haleakalä and how they are related within the unique structure Unit Focus Questions of Hawaiian rain forests. 1) What is the basic structure of the Haleakalä The primary canopy trees in the rain forest of rain forest? Haleakalä and throughout the Hawaiian Islands are öhia (Metrosideros polymorpha) and koa 2) What are some of the plant and animal (Acacia koa). At upper elevations, including the species that are native to the Haleakalä rain cloud forest zone within the rain forest, öhia forest? Where are they found within the rain dominates and koa is absent. In the middle and forest structure? lower elevation rain forests, below about 1250 meters (4100 feet), koa dominates, either inter- 3) How do these plants and animals interact with mixed with ÿöhiÿa, or sometimes forming its each other, and how are they significant in own distinct upper canopy layer above the traditional Hawaiian culture and to people ÿöhiÿa. today? These dominant tree species coexist with many other plants, insects, birds, and other animals. Hawaiian rain forests are among the richest of Hawaiian ecosystems in species diversity, with most of the diversity occurring close to the forest floor. This pattern is in contrast to continental rain forests, where most of the diversity is concentrated in the canopy layer. Today, native species within the rain forests on Haleakalä include more than 240 flowering plants, 100 ferns, somewhere between 600-1000 native invertebrates, the endemic Hawaiian hoary bat, and nine endemic birds in the honey- creeper group. -

Unit PDF Download

Rain Forest Unit 2 Rain Forest Relationships Overview Length of Entire Unit In this unit, students learn about some of the Five class periods main species in the rain forests of Haleakalä and how they are related within the unique structure Unit Focus Questions of Hawaiian rain forests. 1) What is the basic structure of the Haleakalä The primary canopy trees in the rain forest of rain forest? Haleakalä and throughout the Hawaiian Islands are öhia (Metrosideros polymorpha) and koa 2) What are some of the plant and animal (Acacia koa). At upper elevations, including the species that are native to the Haleakalä rain cloud forest zone within the rain forest, öhia forest? Where are they found within the rain dominates and koa is absent. In the middle and forest structure? lower elevation rain forests, below about 1250 meters (4100 feet), koa dominates, either inter- 3) How do these plants and animals interact with mixed with ÿöhiÿa, or sometimes forming its each other, and how are they significant in own distinct upper canopy layer above the traditional Hawaiian culture and to people ÿöhiÿa. today? These dominant tree species coexist with many other plants, insects, birds, and other animals. Hawaiian rain forests are among the richest of Hawaiian ecosystems in species diversity, with most of the diversity occurring close to the forest floor. This pattern is in contrast to continental rain forests, where most of the diversity is concentrated in the canopy layer. Today, native species within the rain forests on Haleakalä include more than 240 flowering plants, 100 ferns, somewhere between 600-1000 native invertebrates, the endemic Hawaiian hoary bat, and nine endemic birds in the honey- creeper group. -

The Threat of the Non-Native Neotropical Rust Puccinia Psidii to Hawaiian Biodiversity and Native Ecosystems: a Case Example of the Need for Prevention

The Threat of the Non-native Neotropical Rust Puccinia psidii to Hawaiian Biodiversity and Native Ecosystems: A Case Example of the Need for Prevention Lloyd Loope, U.S. Geological Survey,Pacific Island Ecosystems Research Center, Haleaka- la Field Station, P.O. Box 369, Makawao, HI 96768; [email protected] Janice Uchida, Department of Plant and Environmental Protection Sciences, University of Hawaii at Manoa, 3190 Maile Way, Honolulu, HI 96822; [email protected] Loyal Mehrhoff, U.S. Geological Survey, Pacific Island Ecosystems Research Center, 677 Ala Moana Boulevard, Suite 615, Honolulu, HI 96813; [email protected] Introduction The threat of invasive species to natural areas presents enormous challenges, but there are opportunities for working toward solutions, often in conjunction with agricultural and forestry perspectives. There is a growing awareness of the danger to botanical biodiversity and conservation from “emerging infectious diseases” that have increased in incidence, geo- graphical distribution, or host range/pathogenicity; have newly evolved characteristics; and/or have been newly discovered (Anderson et al. 2004). There is a heightened concern for forest health due to accelerating worldwide movement of plant pathogens (e.g., with inef- fective quarantine measures) that negatively affect both biodiversity and commercial forestry (Wingfield 2003). An important related concept is that of the ability of fungi to jump to new hosts following anthropogenic introduction. Native hosts are exposed to pathogens with no coevolved recognition or defense mechanism, and microevolution toward increased viru- lence of introduced pathogens can result (Wingfield 2003; Slippers et al. 2005). The rust fungus Puccinia psidii (Basidiomycota, Uredinales: Pucciniaceae), a species first document- ed to have jumped from native guava (Psidium guajava, Myrtaceae) to introduced Eucalyp- tus spp.