Mathtune Tuning Guitars and Reading Music in Major Thirds ∗

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Keeping the Tradition by Marilyn Lester © 2 0 1 J a C K V

AUGUST 2018—ISSUE 196 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM P EE ING TK THE R N ADITIO DARCY ROBERTA JAMES RICKY JOE GAMBARINI ARGUE FORD SHEPLEY Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East AUGUST 2018—ISSUE 196 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 NEw York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : ROBERTA GAMBARINI 6 by ori dagan [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : darcy james argue 7 by george grella General Inquiries: [email protected] ON The COver : preservation hall jazz band 8 by marilyn lester Advertising: [email protected] Encore : ricky ford by russ musto Calendar: 10 [email protected] VOXNews: Lest We Forget : joe shepley 10 by anders griffen [email protected] LAbel Spotlight : weekertoft by stuart broomer US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or vOXNEwS 11 by suzanne lorge money order to the address above or email [email protected] obituaries by andrey henkin Staff Writers 12 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Duck Baker, Stuart Broomer, FESTIvAL REPORT Robert Bush, Thomas Conrad, 13 Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Phil Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, Anders Griffen, CD REviewS 14 Tyran Grillo, Alex Henderson, Robert Iannapollo, Matthew Kassel, Mark Keresman, Marilyn Lester, Miscellany 31 Suzanne Lorge, Marc Medwin, Jim Motavalli, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, Event Calendar 32 John Sharpe, Elliott Simon, Andrew Vélez, Scott Yanow Contributing Writers Mathieu Bélanger, Marco Cangiano, Ori Dagan, George Grella, George Kanzler, Annie Murnighan Contributing Photographers “Tradition!” bellowed Chaim Topol as Tevye the milkman in Fiddler on the Roof. -

2014-03 Programm Domicil.Pdf

fünfundvierzig jahre domicil März 2014 domicil | Hansastraße 7–11, 44137 Dortmund | www.domicil-dortmund.de Sa 01 03 44&more – Die Party ab 40 Mo 03 03 Monday Night Session Fr 07 03 DEW21 Bandwettbewerb “DORTMUND CALLING“ Sa 08 03 SalsaBomba Sa 08 03 SPIN. - Finest Electronic Beats Party Sa 08 03 Kalle Kalima "Klima Kalima" So 09 03 The Aristocrats "Culture Clash Tour 2014" Mo 10 03 Monday Night Session Di 11 03 E-MEX Ensemble: Lady Suit Mi 12 03 ** NEU ** Päng! Do 13 03 LMBN – Slam Lesebühne Fr 14 03 ** NEU ** Friday Night Lounge: About Aphrodite Sa 15 03 Funkhaus Europa Club: Global Player Party Sa 15 03 WDR Funkhaus Europa - Trafi co: Ebo Taylor / Grandbrothers So 16 03 SOUNDZZ Familienkonzert: Jakob und der Kontrabass Mo 17 03 Monday Night Session Di 18 03 Displace Marilyn Mi 19 03 Freistil Jam Fr 21 03 Christoph Stiefel Inner Language Trio Sa 22 03 Nik Bärtsch's Ronin www.gestaltend.de Designkonzeption/Gestaltung: Sa 22 03 30+ Rock Party So 23 03 WDR Big Band feat. Christian McBride Mo 24 03 Monday Night Session Di 25 03 Karl Lippegaus: John Coltrane "Trane-Trance" II Alle Angaben ohne Gewähr. Mi 26 03 Intercontinental – Weltmusik-Session Do 27 03 Oregon Fr 28 03 Paris la nuit Sa 29 03 Jazzmeeting WDR 3: Medeski Martin & Wood feat. Nels Cline Sa 29 03 Soultrippin‘ Club Party Mo 31 03 Monday Night Session Vorschau | im Vorverkauf 3.4. Gianmaria Testa | 10.4. LMBN | 12.4. Aki Takase „New Blues Project“ | 17.4. The Dorf | 24.4. -

September 1988

Cover photo by Ebet Roberts 18 AIRTO He calls himself the "outlaw of percussion" because he breaks all the rules, but that's what has kept Airto in demand with musicians such as Miles Davis, Chick Corea, and Weather Report for almost two decades. His latest rule-breaking involves the use of electronics, but as usual, he has come up with his own way of doing it. by Rick Mattingly 24 GILSON LAVIS Back when Squeeze was enjoying their initial success, drummer Gilson Lavis was becoming increasingly dependent on alcohol. After the band broke up, he conquered his problem, and now, with the re-formed Squeeze enjoying success once again, Lavis is able to put new energy into his gig. by Simon Goodwin 28 BUDDY Photo by Ebet Roberts MILES He made his mark with the Electric Flag, Jimi Hendrix's Band of Gypsies, and his own Buddy Miles Express. Now, active once again with Santana and the California Raisins, Buddy Miles reflects on the legendary music that he was so much a part of. by Robert Santelli 32 DAVE TOUGH He didn't have the flash of a Buddy Rich or a Gene Krupa, but Dave Tough made such bands as Benny Goodman's, Artie Shaw's, and Woody Herman's play their best through his driving timekeeping and sense of color. His story is a tragic one, and it is thus even more Roberts Ebet remarkable that he accomplished so much in his by relatively short life. Photo by Burt Korall VOLUME 12, NUMBER 9 ROCK BASICS PERSPECTIVES Heavy Metal Power Warming Up: Part 1 Fills: Part 1 by Kenny Aronoff by Jim Pfeifer 38 90 UP AND COMING DRUM SOLOIST ROCK'N'JAZZ David Bowler Max Roach: "Jordu" CLINIC by Bonnie C. -

Guitar Tunings

Guitar tunings Guitar tunings assign pitches to the open strings of guitars, including acoustic guitars, electric guitars, and classical guitars. Tunings are described by the particular pitches denoted by notes in Western music. By convention, the notes are ordered from lowest-pitched string (i.e., the deepest bass note) to highest-pitched (thickest string to thinnest).[1] Standard tuning defines the string pitches as E, A, D, G, B, and E, from lowest (low E2) to highest (high E4). Standard tuning is used by most guitarists, and The range of a guitar with standard frequently used tunings can be understood as variations on standard tuning. tuning The term guitar tunings may refer to pitch sets other than standard tuning, also called nonstandard, alternative, or alternate. Some tunings are used for 0:00 MENU particular songs, and might be referred to by the song's title. There are Standard tuning (listen) hundreds of such tunings, often minor variants of established tunings. Communities of guitarists who share a musical tradition often use the same or similar tunings. Contents Standard and alternatives Standard Alternative String gauges Dropped tunings Open tunings Major key tunings Open D Open C Open G Creating any kind of open tuning Minor or “cross-note” tunings Other open chordal tunings Modal tunings Lowered (standard) E♭ tuning D tuning Regular tunings Major thirds and perfect fourths All fifths and “new standard tuning” Instrumental tunings Miscellaneous or “special” tunings 1 15 See also Notes Citation references References Further reading External links Standard and alternatives Standard Standard tuning is the tuning most frequently used on a six-string guitar and musicians assume this tuning by default if a specific alternate (or scordatura) is not mentioned. -

Jazz Melody Generation and Recognition

Jazz Melody Generation and Recognition Joseph Victor December 14, 2012 Introduction In this project, we attempt to use machine learning methods to study jazz solos. The reason we study jazz in particular is for the simplicity of the song structure and the complexity and diversity of the solos themselves. A typical jazz song has an introduction, followed by each musician taking a turn improvising a melody over a fixed set of chord changes. The chord changes constrain what note choices a soloist can make, but also guide the melodic evolution of the solos. Abstractly, a jazz musician is a machine which reads in a set of chord changes and non-deterministically outputs a melody1. There are then two obvious problems one can attempt to solve computationally. The first is generation; can a computer be a jazz musician? The second is classification; given a solo, can a computer guess the chord changes which inspired them? One should believe the first question is possible, although admittedly hardworking musicians should always be able to beat it. One should believe the second question is possible because if one listens to a soloist without the accompaniment one can still \hear the changes", especially with the jazz greats, so long as the soloist isn't playing anything too wild. The hope is that a computer can statistically hear the changes at least as well as a toe-tapper. The basic philosophy is this: fine a bunch of reasonably structured jazz melodies (that is, 4/4 having the format described above), chop them up so we have a bunch of chord- progression/melody-snippet pairings of the same length and analyze them to solve the two problems above. -

Tooele Transcript Bulletin

www.tooeletranscript.com TUESDAY Leaping frogs keep things hopping at Stansbury Days See A10 TOOELETRANSCRIPT BULLETIN August 22, 2006 SERVING TOOELE COUNTY SINCE 1894 VOL. 113 NO. 26 50 cents Walgreens buys out longtime Mustard Tooele pharmacy Dave’s Drug burning Pharmacists, staff will move to corporation’s new store by Karen Hunt Kind of. helm, an overwhelming number process STAFF WRITER While the longtime city hall- say, sometimes grudgingly, that After this Thursday, Dave’s mark will close its doors, the they’ll do their business at the Drugs will be no more than a entire pharmacy staff, complete corporate pharmacy chain. with owner Dave Bickmore, will “I know I’ll have to go where heats up memory. Tooele City’s community move over to Walgreens. The pre- they go. I’ve been a customer of pharmacy has made a deal with scription files for Dave’s Drugs theirs for a long time and there’s by Mark Watson Walgreens, the corporate giant customers will be transferred to a lot of things they do for me. I’m STAFF WRITER preparing to open this week on the new location for opening day not just up and changing this late The final major phase in the the corner of Main Street and Friday, Aug. 25. in the game,” said Kathy Madill, destruction of chemical weap- Utah Avenue in Tooele. Customers can choose to main- while standing in line at Dave’s ons started Friday at Tooele Chemical Disposal Facility at The deal will mark the end of tain their records with Walgreens Drugs Monday. -

Impro-Visor Leadsheet Notation

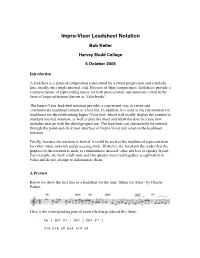

Impro-Visor Leadsheet Notation Bob Keller Harvey Mudd College 5 October 2005 Introduction A leadsheet is a musical composition represented by a chord progression and a melody line, usually on a single musical staff. Because of their compactness, leadsheets provide a common means of representing music for both professionals and amateurs, often in the form of large collections known as “fake books”. The Impro-Visor leadsheet notation provides a convenient way to create and communicate leadsheet content as a text file. In addition, it is used as the file notation for leadsheets for the forthcoming Impro-Visor tool, which will readily display the content in standard musical notation, as well as play the sheet and allow the user to create new melodies that go with the chord progression. The leadsheet can alternatively be entered through the point-and-click user interface of Impro-Visor and saved in the leadsheet notation. Finally, because the notation is formal, it could be used as the medium of representation for other music notation and processing tools. However, we forewarn the reader that the purpose of the notation is more to communicate musical value and less to specify layout. For example, we view a half-note and two quarter notes tied together as equivalent in value and do not attempt to differentiate them. A Preview Below we show the first line of a leadsheet for the tune “Blues for Alice” by Charlie Parker. Here is the corresponding part of a text file that produced this sheet: F6 | Em7 A7 | Dm7 | Cm7 F7 | f+4 c+8 a8 e+4 c+8 a8 d+8 e+8 cb8 d+8 db+8 bb8 g8 ab8 a4 f8 d8 g8 a8 f8 e8 eb8/3 g8/3 bb8/3 d+8 db+8 r8 f8 f8/3 g8/3 f8/3 This document explains how to create the notation, with hopes that the reader will begin using the notation for creating leadsheets and possibly using them in Improvisor. -

KPCC-KPCV-KUOR Quarterly Report JAN-MAR 2012

Quarterly Programming Report Jan- Mar 2012 KPCC / KPCV / KUOR Date Key Synopsis Guest/Reporter Duration Pasadena Police Department will deploy more officers as Occupy activists plan to demonstrate at the 1/1/2012 POLI Rose Parade. CC :19 Skiers and snowboarders across the western United States face a "snow drought" this winter on some 1/1/2012 SPOR of their favorite slopes. Unknown :16 The three-year old Clean Trucks Program at the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach moves into its 1/1/2012 TRAN final phase as the year begins. Peterson :58 1/1/2012 LAW Another dozen arson fires broke out overnight in Los Angeles and West Hollywood. CC :17 1/1/2012 ART Native American creation story and bird songs come alive in new Riverside art exhibition. Cuevas 1:33 1/1/2012 MEDI We asked KPCC listeners to look back on 2011 and ahead to 2012. CC :13 1/1/2012 DC Congressmangpyy shares a New Year's Day breakfast recipe. Felde 1:33 contract with United Teachers Los Angeles – an unprecedented agreement that Deasy called “groundbreaking work,” aimed at providing more freedom for teachers, school administrators and 1/2/12 YOUT parents top,gpggpp, manage their respective schools. John Deasy 00:31 of course. Comedy Congress has hung up its Christmas stocking and finds it full of Mitt and Newt and Barack – and it’s our holiday gift to you. Perry ups the voting age; Obama very politely asks Iran for his Alonzo Bodden, Greg 1/2/12 POLI drone back and we play the highlight reel of Cain’s self-described brain twirlings! And just as we thoughtProops, Ben Gleib 00:65 Dr. -

Ff :IAY 1996 ~ ~ RECEIVED ~ Hanford Update Article ~ EDMC Aj ~ Q), This Agenda Item Was Deferred to the Following Week

. ,. ·:.' I ' 0044051 ;: Meeting Minutes Columbia River Comprehensive Impact Assessment Weekly Management Meeting May 7, 1996 ETB Building, Columbia River Room, 1:00 - 2:30 Attendees(*)/Distribution(#): Charlie Brandt, PNNL# Stuart Harris, CTUIR*# Roger Ovink, BHI# Amoret Bunn, Dames & Moore@*# RD Hildebrand, RL*# Doug Palenshus, Ecology*# Sandra Cannon, PNNL *# Dave Holland, Ecology*# Ralph Patt, Oregon*# Paul Danielson, NPT*# A Knepp, BHI# Stan Sobczyk, NPT*# Greg deBruler, HAB# Jay McConnaughey, WDFW# Bob Stewart, RL# Kevin Clarke, RL# ,- .. Terri Miley, PNNL# Mike Thompson, RL *# Roger Dirkes, PNNL *# Dick Moos, BHI# JR Wilkinson, CTUIR# Sue Finch, PNNL@*# Nancy Myers, BHI*# Thomas W. Woods, YIN# Larry Gadbois, EPA# Bruce Napier, PNNL# Jerry Yokel, Ecology# Lino G. Niccoli, YIN*# Admin Records-CRCIA# ~,&1920,27q "<o /' ~~ Summary of Discussions: I@ "L' 'V~ In Bob Stewart's absence, Dave Holland ran the meeting. ff :IAY 1996 ~ ~ RECEIVED ~ Hanford Update Article ~ EDMC Aj ~ Q), This agenda item was deferred to the following week. Comments have been received an CS' e ~ti, outreach team will consolidate/incorporate the comments at the 5/8/96 weekly outreach meet '-.,,,, ~ updated article will be faxed out to the team for review. The due date for submission of the article 1s May 15 . Nancy Myers was assigned an action to determine if the date could be extended. If the date cannot be extended, .the article will be submitted based on comments received and a final version handed out at the May 14 meeting. Proposal for Public Outreach Team This agenda item was deferred to the following week. Preface Discussion The attached preface was handed out to team members. -

Crinew Music Re 1Ort

CRINew Music Re 1 ort MARCH 27, 2000 ISSUE 659 VOL. 62 NO.1 WWW.CMJ.COM MUST HEAR Sony, Time Warner Terminate CDnow Deal Sony and Time Warner have canceled their the sale of music downloads. CDnow currently planned acquisition of online music retailer offers a limited number of single song down- CDnow.com only eight months after signing loads ranging in price from .99 cents to $4. the deal. According to the original deal, A source at Time Warner told Reuters that, announced in July 1999, CDnow was to merge "despite the parties' best efforts, the environment 7 with mail-order record club Columbia House, changed and it became too difficult to consum- which is owned by both Sony and Time Warner mate the deal in the time it had been decided." and boasts a membership base of 16 million Representatives of CDnow expressed their customers; CDnow has roughly 2.3 million cus- disappointment with the announcement, and said tomers. With the deal, Columbia House hoped that they would immediately begin seeking other to enter into the e-commerce arena, through strategic opportunities. (Continued on page 10) AIMEE MANN Artists Rally Behind /14 Universal Music, TRNIS Low-Power Radio Prisa To Form 1F-IE MAN \NHO During the month of March, more than 80 artists in 39 cities have been playing shows to raise awareness about the New Latin Label necessity for low power radio, which allows community The Universal Music Group groups and educational organizations access to the FM air- (UMG) and Spain's largest media waves using asignal of 10 or 100 watts. -

KPCC-KPCV-KUOR Quarterly Report OCT-DEC 2011

Quarterly Programming Report Oct-Dec 2011 KPCC / KPCV / KUOR Date Key Synopsis Guest/Reporter Duration 10/1/2011 HEAL The first case of the new session of the U.S. Supreme Court will involve poor and disabled Californians. Felde :59 This weekend marks the grand opening of the biggest and most ambitious art project Southern California - and maybe the world - has ever seen. For the next six months, 60 cultural institutions and 70 galleries are collaborating on "Pacific Standard Time," which documents art made in LA from 1945 to 1980. The Getty Foundation is footing much of the bill with ten-million dollars in grants, and on Tuesday 10/1/2011 ART the Getty hosted the press opening. Off-Ramp's John Rabe was there. John Rabe 8:34 Since Pacific Standard Time is all about L.A., we’ve asked some of the artists who were making art in the city from 1945 to 1980 to take us to three places here that are important to them. Anywhere. We’re 10/1/2011 ART starting this week with performance artist Barbara T Smith. Kevin Ferguson 5:39 Off-Ramp host John Rabe talks with Jim Meskimen, YouTube sensation, actor and man of a thousand voices, including Robin Williams, Kirk Douglas, Charleton Heston, Woody Allen, Droopy Dog, President George W Bush and Harvey Keitel. His show "Jimpressions" comes to The Acting Center at Hollywood 10/1/2011 ART and Western on October 7 & 8. John Rabe 7:21 "Andy Rooney" has long been a staple of Off-Ramp. Here, he muses about his 320 years on CBS, and 10/1/2011 ART the people who've made a living imitating him. -

Jazz Guitarists

List of Jazz Guitarists 1. Blake Aaron 2. Eivind Aarset 3. Rez Abbasi 4. John Abercrombie 5. Paul Abler 6. Steve Abshire 7. Morris Acevedo 8. Bernard Addison 9. Steve Adelson 10. Dan Adler 11. Ron Affif 12. Noel Akchote 13. Jan Akkerman 14. Odd Steinar Albrigtsen 15. Howard Alden 16. Johnny Alegre 17. Oscar Alemán 18. Glenn Alexander 19. Neal Alger 20. Laurindo Almeida 21. Peter Almqvist 22. Frode Alnæs 23. Leonardo Amuedo 24. Chuck Anderson 25. Tuck Andress 26. John Anello Jr 27. Michael Anthony 28. Ron Anthony 29. Marc Antoine 30. Bruce Arnold 31. Irving Ashby 32. Dave Askren 33. Badi Assad 34. Gustavo Assis-Brasil 35. Chet Atkins 36. Erich Avinger B 37. Elek Bacsik 38. Mike Baggetta 39. Derek Bailey (the most radical) 40. Sheryl Bailey (blazing style, need to check out) 41. Bob Bain 42. Clint Baker 43. Duck Baker 44. Matt Balitsaris 45. Dave Barbour 46. A Spencer Barefield 47. Danny Barker 48. Everett Barksdale 49. Junior Barnard 50. George Barnes 51. Jeff Barone 52. Carl Barry 53. John Basile 54. Frode Barth 55. Billy Bauer 56. Billy Bean 57. Gerry Beaudoin 58. Jeff Beck 59. Joe Beck 60. David Becker 61. Jean-Marc Belkadi 62. Robert Bell 63. Roni Ben-Hur 64. George Benson 65. Rolf Berg 66. Gonzalo Bergara 67. Chris Bergson 68. Randy Bernsen’s 69. Peter Bernstein 70. Gene Bertoncini 71. Mads Berven 72. Skeeter Best 73. Ed Bickert 74. Brian Blade 75. Jack Bland 76. Michael Bocian 77. Pascal Bokar 78. Paul Bollenback 79. Luiz Bonfá 80. Perry Botkin Sr 81.