Financial Access for Immigrants: Lessons from Diverse Perspectives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Atletismo Athletics

Memorias / Memoirs Atletismo Athletics Final de los 100 metros que ganó Rolando Palacios de Honduras Final of 100 meters won by Rolando Palacios from Honduras Las competencias de atletismo se celebraron en The Athletics competitions were held at the historie el histórico Estadio Heriberto Jara Corona de la Heriberto Jara Corona Stadium in the city ofXalapa, ciudad de Xalapa que fue inaugurado en 1922 which was inaugurated in 1922 and has been y se ha mantenido activo por más de 90 años. active for more than 90 years. For the jirst time Por primera vez en la historia de los Juegos el in the history of the Games the athletics was held atletismo se celebró en una subsede y no en la in a sub-venue and not in the main venue of the sede principal de los Juegos que fue Veracruz. La Games that was Veracruz. The competition brought competencia reunió a los 31 países de la ODECABE, together the 31 countries of CACSO, with the con la participación de 426 competidores, (245 participation of 426 competitors, (245 men - 181 hombres - 181 mujeres), mejorándose 12 marcas women), improving 12 records of the Games. The de los Juegos. Los países con más participantes countries with more participants were Mexico with fueron México con 83, Cuba 67, Colombia 43 83, Cuba 67, Colombia 43 and Venezuela 34. Ofthe y Venezuela 34. De los países participantes, participating countries, 19 of them won medals, 19 de ellos ganaron medallas, dominando la Cuba dominated the competition that accumulated competencia Cuba que acumuló 46 preseas, con 46 medals, with 23 gold, 15 silver and 8 bronze. -

Savings Bank

Savings Bank A savings bank is a financial institution whose primary purpose is accepting savings deposits and paying interest on those deposits. They originated in Europe during the 18th century with the aim of providing access to savings products to all levels in the population. Often associated with social good these early banks were often designed to encourage low income people to save money and have access to banking services. They were set up by governments or by or socially committed groups or organisations such as with credit unions. The structure and legislation took many different forms in different countries over the 20th century. The advent of internet banking at the end of the 20th century saw a new phase in savings banks with the online savings bank that paid higher levels of interest in return for clients only having access over the web. History In Europe, savings banks originated in the 19th or sometimes even the 18th century. Their original objective was to provide easily accessible savings products to all strata of the population. In some countries, savings banks were created on public initiative, while in others, socially committed individuals created foundations to put in place the necessary infrastructure. In 1914, the New Student's Reference Work said of the origins:[1] France claims the credit of being the mother of savings banks, basing this claim on a savings bank said to have been established in 1765 in the town of Brumath, but it is of record that the savings bank idea was suggested in England as early as 1697. -

Ten Questions Concerning the Spanish Banking Sector

TEN QUESTIONS CONCERNING THE SPANISH BANKING SECTOR Santiago Carbó Valverde (University of Granada) Joaquín Maudos Villarroya (Ivie and University of Valencia) “Fate gives us the hand, and we play the cards” William Shakespeare 1. Introduction The Spanish banking sector finds itself at a delicate crossroads at which an important number of questions remain unresolved. Together with the much-awaited economic recovery and the reduction of unemployment, the resolution of the problems of solvency and the need for restructuring which affect financial intermediaries constitute probably the most important and urgent challenges which must be faced in Spain. A solution to these difficulties of the financial system is a necessary condition for sustainable and lasting recovery. If the situation facing the Spanish banking sector is analysed, similarities are clear with other international experiences, but so is a problem specific to Spain –in which the exposure of the banking sector to the domestic property market is significant- which requires its own solutions and which, for various reasons, is making itself felt later than in the majority of neighbouring economies. This time lag –considered by many to be involuntary, since the crisis arrived relatively late to Spain- is becoming a cause for concern since, in specific scenarios, greater efforts than those foreseen may be necessary to tackle the restructuring and reassessment required and avoid a greater crisis. The present article reviews the principal questions concerning Spanish financial intermediaries in the spring of 2010, grouped together into ten points. In addition to this fairly broad but not necessarily exclusive or exhaustive recapitulation, an attempt is made 1 to repudiate certain convictions which have established something of a foothold in recent months and which require clarification. -

Foreign Passports (See Pages 4 & 5 for List of Department Approved Passports)

AB 60 – Document Options for a California Driver License Customers applying for a driver license must provide Proof of Identity and California Residency if they do not have satisfactory proof of legal presence. Use the following guideline to help you determine the documents that are needed when applying for a driver license. PROOF OF IDENTITY: ONE (1) OF THE FOLLOWING DOCUMENTS California Driver License or California Identification Card: California Driver License (issued 10/2000 or later) California Identification Card (issued 10/2000 or later) Foreign Document that is valid, approved by the department and electronically verified by the department with the country of origin, such as: Mexican Federal Electoral Card (Instituto Federal Electoral (IFE) Credencial para Votar – 2013 version) Mexican Passport (issued in 2008 or later) Mexican Consular Card (Matricula Consular - 2006 and 2014 versions) Foreign Passport that is valid, approved by the department and accompanied with a social security number that is electronically verifiable with the Social Security Administration. Foreign Passport (see page 4 & 5 for list of department approved passports) -----OR------ TWO (2) DOCUMENTS FROM TABLE A --or-- ONE (1) DOCUMENT FROM TABLE A and ONE (1) DOCUMENT FROM TABLE B Table A Table B Foreign Document that is valid and approved by the department but cannot be Foreign Birth Certificate: electronically verified by the department with the country of origin, such as: Certified copy issued by Argentinian Identification Card (Documento Nacional de Identidad (DNI) – 2012 a national civil registry version) within six (6) months of Chilean Identification Card (Cedula de Identidad – 2013 version) the application date (for El Salvadorian Identification Card (Documento Unico de Identidad (DUI) – 2010 a CA driver license) that version) contains an embedded photo of the applicant. -

The First Savings Banks in Latin America

The First Savings Banks in Latin America: Cuba and Puerto Rico (1840-1898- Angel Pascual MARTINEZ SOTO March 2011 World Savings Banks Institute - aisbl – European Savings Banks Group – aisbl Rue Marie-Thérèse, 11 ■ B-1000 Bruxelles ■ Tel: + 32 2 211 11 11 ■ Fax: + 32 2 211 11 99 E-mail: first [email protected] ■ Website: www.savings-banks.com THE FIRST SAVINGS BANKS IN LATIN AMERICA: CUBA AND PUERTO RICO (1840-1898) Angel Pascual Martinez Soto, Professor, University of Murcia Angel Pascual Martinez Soto (1955), Senior Lecturer in Economic History and Director of the Department of Applied Economics of the University of Murcia (Spain), focuses predominantly on the study of several aspects of the financial history of Spain. He contributes to the main Spanish journals in the field, mainly on credit cooperatives and saving banks. Other research topics are the demography and standards of living in the Spanish mining industry. His recent work examines the financial system during the Spanish colonial period in Cuba, Puerto Rico and the Philippines. Despite the progress made in researching the history of savings banks in Spain, there are still aspects that remain largely unknown, especially with regard to their introduction in the colonial environments of Hispanic America and the Philippines. This paper studies these hitherto largely ignored institutions in Cuba and Puerto Rico during the period from 1835 to 1898.1 We are therefore dealing with a subject that is novel and, in our opinion, important in order to better understand the history of this type of entity both in Europe and in other non-European territories. -

The Banking Systems of Germany, the UK and Spain from a Spatial Perspective: the Spanish Case

IAT Discussion Paper 18|02 The Banking Systems of Germany, the UK and Spain from a Spatial Perspective: The Spanish Case Stefan Gärtner and Jorge Fernandez Institute for Work and Technology Research Department: Spatial Capital Westphalian University of Applied Sciences Copyright remains with the author. Discussion papers of the IAT serve to disseminate the research results of work in pro- gress prior to publication to encourage the exchange of ideas and academic debate. Inclusion of a paper in the discussion paper series does not constitute publication and should not limit publication in any other venue. The discussion papers published by the IAT represent the views of the respective author(s) and not of the institute as a whole. © IAT 2018 2 The Banking Systems of Germany, UK and Spain from a Spatial Perspective: The Spanish Case Stefan Gärtner* and Jorge Fernández April 2018 Abstract When looking at the Spanish banking market through a German lens, the differences between the banking markets in these countries and between decentralised and centralised systems with regard to the SME‐credit decision‐making process become obvious. Despite our hypotheses that Spanish savings banks were similar to German savings banks until the crisis, or at least until liberalisation and before the break‐up of the regional principle, we came to the conclusion that they were never as significant as savings banks in Germany, at least not for SME finance. Notwithstanding recent initiatives to create a common European market and to integrate diverse national banking systems, the European financial system remains spatially complex and uneven, particularly with respect to the degree of geographical concentration. -

Banking Regulation – 2Nd Edition Chapter: Spain

BANKING REGULATION – 2ND EDITION CHAPTER: SPAIN Fernando Mínguez Hernández Íñigo de Luisa Maíz Rafael Mínguez Prieto Global Legal Insights, June 2015 Introduction From late 2008, the Spanish banking sector has lived through a constant and deep restructuring process ultimately driven by regulatory responses to the severe crisis the sector faced as a result of the abrupt end of the long period of growth after Spain’s incorporation to the Euro in 1998. Fortunately, the worst of the crisis seems over and we face now a more stable, more transparent and sounder financial sector. Until the beginning of this decade, it was accurate to describe the Spanish banking sector as quite unique among its European counterparts. While the country was, and is, home to two of the world largest banking corporations (Santander and BBVA) – present in other European jurisdictions and outside the EU, most significantly in Latin America – such large corporations did not account for more than 30% of the domestic deposit market share; the rest was in the hands of many other institutions, including a wide array of mid- and small-sized companies. Bank of Spain’s census as of early 2009 comprised some 80 private banks (of which roughly 10 have a significant market share), 80 credit cooperatives (accounting, altogether, for 5% of the share, approximately) and 45 savings banks (cajas de ahorros), representing, roughly, 50% of the market. Branches of foreign institutions (almost exclusively EU-incorporated) were and are present but hold a negligible share of the retail market1. The relevant presence of savings banks was doubtlessly the most salient feature of the Spanish Banking system. -

International Savings Banks

INTERNATIONAL SAVINGS BANKS 21 August 2021 The Savings Banks Organisation in Spain Since the end of the 1980s, when the regional principle was abolished, in Spain, cooperation between savings banks has been Author: abandoned in favour of growth of the institutions. Since then, the Jana Gieseler - DSGV number of savings banks in Spain has fallen sharply. In return, the market share of savings banks in the lending business has risen from approx. 28% to approx. 36%. A law passed in July 2010 allowed the separation of the public interest orientation from the banking business. The tasks oriented towards the common good (in Spain: "obra social") remained in the sponsoring savings bank, which was run as a foundation under private law. The banking business could be outsourced to a (listed) bank with the aim of being raising equity capital on the market. While the sponsoring foundations continued to exist for the most part, the bank holding companies experienced two waves of mergers until 2012, which resulted in a complete reorganisation of the sector until 2014. The financial institutions CaixaBank and Bankia merged in March 2021 to form CaixaBank. The merger is considered one of the largest in Spain. Today, there are only eight savings banks left. Two savings banks remained in their old form. The other six are credit institutions derived from savings banks. These are supported by 13 banking foundations (former cajas). The average balance sheet total of these holdings is about EUR 103.5 billion. 1 The Spanish banking market In macroeconomic terms, the banking sector in Spain is of above- average importance compared to other European countries. -

GAO-04-881 Border Security: Consular Identification Cards

United States Government Accountability Office Report to Congressional Requesters GAO August 2004 BORDER SECURITY Consular Identification Cards Accepted within United States, but Consistent Federal Guidance Needed GAO-04-881 August 2004 BORDER SECURITY Consular Identification Cards Accepted Highlights of GAO-04-881, a report to within United States, but Consistent Congressional Requesters Federal Guidance Needed Several state and local government Consular identification cards are issued by some governments to help agencies and financial institutions identify their citizens living in a foreign country. The cards do not certify accept consular identification (CID) legal residence within a country; thus, cardholders may be either legal or cards, which are issued by foreign undocumented aliens. CID cards benefit the bearers by enabling them, in governments to their citizens living some instances, to use this form of identification to obtain driver’s licenses, abroad. Mexico issued more than 2.2 open bank accounts, show proof of identity to police, and gain access to million CID cards in 2002-2003 and Guatemala issued approximately other services. 89,000 from mid-2002 to 2003. Critics of CID cards say their acceptance Mexico and Guatemala each take multiple steps to help ensure that the facilitates the unlawful stay within process for qualifying applicants seeking to obtain CID cards verifies the the United States of undocumented applicants’ identities. After receiving criticism about the reliability of its CID aliens and may provide opportunities card, Mexico took steps to improve identity verification procedures for its for terrorists to remain undetected in CID card issuance process. However, the Mexican issuance policy still relies this country. -

0 E Event TD

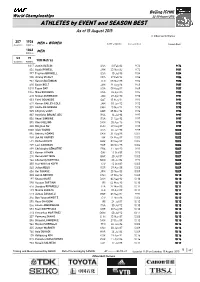

Beijing (CHN) World Championships 22-30 August 2015 ATHLETES by EVENT and SEASON BEST As of 15 August 2015 i = Indoor performance 207 1936 Countries Athletes MEN + WOMEN DATE of BIRTH Personal Best Season Best 1043 Athletes MEN 53 75 Countries Athletes 100 Metres 1017 Justin GATLIN USA10 Feb 82 9.749.74 634 Asafa POWELL JAM23 Nov 82 9.729.81 997 Trayvon BROMELL USA10 Jul 95 9.849.84 500 Jimmy VICAUT FRA27 Feb 92 9.869.86 937 Keston BLEDMAN TTO08 Mar 88 9.869.86 620 Usain BOLT JAM21 Aug 86 9.589.87 1018 Tyson GAY USA09 Aug 82 9.699.87 1054 Mike RODGERS USA24 Apr 85 9.859.88 618 Nickel ASHMEADE JAM07 Apr 90 9.909.91 831 Femi OGUNODE QAT15 May 91 9.919.91 619 Kemar BAILEY-COLE JAM10 Jan 92 9.929.92 309 Andre DE GRASSE CAN10 Nov 94 9.959.95 529 Chijindu UJAH GBR05 Mar 94 9.969.96 837 Henricho BRUINTJIES RSA16 Jul 93 9.979.97 856 Akani SIMBINE RSA21 Sep 93 9.979.97 895 Kim COLLINS SKN05 Apr 76 9.969.98 338 Bingtian SU CHN29 Aug 89 9.999.99 1068 Isiah YOUNG USA05 Jan 90 9.9910.00 894 Antoine ADAMS SKN31 Aug 88 10.0110.03 958 Jak Ali HARVEY TUR04 May 89 10.0310.03 527 Richard KILTY GBR02 Sep 89 10.0510.05 209 Levi CADOGAN BAR08 Nov 95 10.0610.06 499 Christophe LEMAITRE FRA11 Jun 90 9.9210.07 321 Kemar HYMAN CAY11 Oct 89 9.9510.07 210 Ramon GITTENS BAR20 Jul 87 10.0210.07 764 Churandy MARTINA NED03 Jul 84 9.9110.08 355 Hua Wilfried KOFFI CIV12 Oct 87 10.0510.09 548 Julian REUS GER29 Apr 88 10.0510.09 656 Kei TAKASE JPN25 Nov 88 10.0910.09 303 Aaron BROWN CAN27 May 92 10.0510.10 197 Shavez HART BAH06 Sep 92 10.1010.10 598 Hassan TAFTIAN IRI04 -

RESULTS 100 Metres Men - Preliminary Round First 3 in Each Heat (Q) and the Next 2 Fastest (Q) Advance to the 1St Round RESULT CORRECTED for ATHLETE BURKE (BUR)

REVISED London World Championships 4-13 August 2017 RESULTS 100 Metres Men - Preliminary Round First 3 in each heat (Q) and the next 2 fastest (q) advance to the 1st Round RESULT CORRECTED FOR ATHLETE BURKE (BUR) RECORDS RESULT NAME COUNTRY AGE VENUE DATE World Record WR 9.58 Usain BOLT JAM 23 Berlin (Olympiastadion) 16 Aug 2009 Championships Record CR 9.58 Usain BOLT JAM 23 Berlin (Olympiastadion) 16 Aug 2009 World Leading WL 9.82 Christian COLEMAN USA 21 Eugene (Hayward Field), OR 7 Jun 2017 Area Record AR National Record NR Personal Best PB Season Best SB 4 August 2017 19:05 START TIME 21° C 60 % +1.4 m/s TEMPERATURE HUMIDITY Heat 1 4 WIND PLACE NAME COUNTRY DATE of BIRTH LANE RESULT REACTION Fn 1 Emmanuel MATADI LBR 15 Apr 91 6 10.27 Q 0.196 2 Brendon RODNEY CAN 9 Apr 92 3 10.37 Q 0.170 3 Mark Otieno ODHIAMBO KEN 11 May 93 7 10.40 Q 0.184 4 Phearath NGET CAM 27 Mar 93 4 10.99 SB 0.169 5 Masbah AHMMED BAN 11 Mar 95 8 11.08 0.186 6 Mohamed Lamine DANSOKO GUI 15 Mar 98 2 11.41 SB 0.162 7 Dysard DAGEAGO NRU 24 Oct 94 5 11.60 0.172 4 August 2017 19:10 START TIME 21° C 60 % +1.1 m/s TEMPERATURE HUMIDITY Heat 2 4 WIND PLACE NAME COUNTRY DATE of BIRTH LANE RESULT REACTION Fn 1 Emre Zafer BARNES TUR 7 Nov 88 4 10.22 (.217) Q 0.164 2 Chavaughn WALSH ANT 29 Dec 87 6 10.44 Q 0.171 3 Hassan SAAID MDV 4 Mar 92 2 10.45 Q 0.194 4 Dyland SICOBO SEY 27 Feb 97 7 11.01 0.171 5 Jeki LANKI MHL 14 Mar 95 8 11.91 (.908) PB 0.216 6 Mobera TONANA KIR 6 Feb 98 3 11.91 (.909) SB 0.180 7 Ielu TAMOA TUV 17 Aug 93 5 12.12 PB 0.186 4 August 2017 19:16 START TIME -

START LIST 100 Metres Men - Preliminary Round First 3 in Each Heat (Q) and the Next 2 Fastest (Q) Advance to the 1St Round

London World Championships 4-13 August 2017 START LIST 100 Metres Men - Preliminary Round First 3 in each heat (Q) and the next 2 fastest (q) advance to the 1st Round RECORDS RESULT NAME COUNTRY AGE VENUE DATE World Record WR 9.58 Usain BOLT JAM 23 Berlin (Olympiastadion) 16 Aug 2009 Championships Record CR 9.58 Usain BOLT JAM 23 Berlin (Olympiastadion) 16 Aug 2009 World Leading WL 9.82 Christian COLEMAN USA 21 Eugene (Hayward Field), OR 7 Jun 2017 i = Indoor performance Heat 1 4 4 August 2017 19:00 START TIME LANE NAME COUNTRY DATE of BIRTH PERSONAL BEST SEASON BEST 2 Mohamed Lamine DANSOKO GUI 15 Mar 98 10.93 3 Brendon RODNEY CAN 9 Apr 92 10.18 10.18 4 Phearath NGET CAM 27 Mar 93 10.87 5 Dysard DAGEAGO NRU 24 Oct 94 11.24 11.24 6 Emmanuel MATADI LBR 15 Apr 91 10.14 10.18 7 Mark Otieno ODHIAMBO KEN 11 May 93 10.14 10.14 8 Masbah AHMMED BAN 11 Mar 95 10.72 10.88 Heat 2 4 4 August 2017 19:08 START TIME LANE NAME COUNTRY DATE of BIRTH PERSONAL BEST SEASON BEST 2 Hassan SAAID MDV 4 Mar 92 10.33 10.37 3 Mobera TONANA KIR 6 Feb 98 11.89 12.16 4 Emre Zafer BARNES TUR 7 Nov 88 10.12 10.17 5 Ielu TAMOA TUV 17 Aug 93 12.73 12.73 6 Chavaughn WALSH ANT 29 Dec 87 10.17 10.17 7 Dyland SICOBO SEY 27 Feb 97 10.33 10.33 8 Jeki LANKI MHL 14 Mar 95 Heat 3 4 4 August 2017 19:16 START TIME LANE NAME COUNTRY DATE of BIRTH PERSONAL BEST SEASON BEST 2 Rolando PALACIOS HON 3 May 87 10.22 10.54 3 Ján VOLKO SVK 2 Nov 96 10.16 10.16 4 Said GILANI AFG 5 Feb 96 11.33 5 Paul MA'UNIKENI SOL 14 Apr 00 11.52 11.52 6 Mario BURKE BAR 18 Mar 97 10.17 10.17 7 Hanh BUI BA