Download (2MB)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Title: Stone of Destiny

Edinburgh Research Explorer Stone of Destiny Citation for published version: Murray, J 2015, Stone of Destiny. in B Nowlan & Z Finch (eds), Directory of World Cinema: Scotland. 1st edn, Intellect Ltd., Bristol/Chicago, pp. 174-176. Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: Directory of World Cinema: Scotland Publisher Rights Statement: © Murray, J. (2015). Stone of Destiny. In B. Nowlan, & Z. Finch (Eds.), Directory of World Cinema: Scotland. (1st ed., pp. 174-176). Bristol/Chicago: Intellect Ltd . General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 23. Sep. 2021 Title: Stone of Destiny Country of Origin: Canada, UK Year: 2008 Language: English Production Companies: Infinity Features Entertainment, The Mob Film Company, Alliance Films, Téléfilm Canada, Scottish Screen National Lottery Fund, The Harold Greenberg Fund Filming Location: Arbroath, Glasgow, London, Vancouver Director: Charles Martin Smith Producers: Andrew Boswell, Alan Martin, Rob Merilees Screenwriters: Charles Martin Smith, Ian Hamilton Art Director: Andy Thomson Editor: Fredrik Thorsen Runtime: 96 minutes Cast (Starring): Charlie Cox, Kate Mara, Stephen McCole, Billy Boyd, Robert Carlyle Synopsis: Based on a true story, Stone of Destiny narrates the tale of a daring heist jointly fuelled by the audacity of young minds and the tenacity of old mindsets. -

Scottish Election Briefing 2011 Contents

Scottish Election Briefing 2011 Contents 3 Introduction 9 Scottish National Party 13 Scottish Labour 18 Scottish Conservatives 22 Scottish Liberal Democrats 26 Scottish Green Party 27 UK Independence Party 28 Christian Peoples Alliance 29 Scottish Christian Party 30 Legislation summary: Scottish Parliament 2007-2011 35 References 38 Notes Copyright The Christian Institute 2011 Printed in April 2011 Published by The Christian Institute Wilberforce House, 4 Park Road, Gosforth Business Park Newcastle upon Tyne, NE12 8DG All rights reserved No part of this publication may be reproduced, or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, mechanical, electronic, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of The Christian Institute. The Christian Institute is a Company Limited by Guarantee, registered in England as a charity whose main object is “the furtherance and promotion of the Christian Religion in the United Kingdom and elsewhere”. Company No. 263 4440; Charity No. 100 4774. A charity registered in Scotland. Charity No. SC039220. 2 Introduction Elections for the Scottish Parliament will take – the SNP, Labour, the Conservatives and the place on 5 May. As Christian citizens we should Liberal Democrats. There are other parties think carefully about how to vote. standing in the Scottish Parliament elections; The Christian Institute is a registered charity we have also included some of the known and cannot endorse any political party or policies of the Scottish Green Party and UKIP, candidate in elections. We cannot tell you who parties which have representation at national to vote for. That is a matter for you. -

Media Culture for a Modern Nation? Theatre, Cinema and Radio in Early Twentieth-Century Scotland

Media Culture for a Modern Nation? Theatre, Cinema and Radio in Early Twentieth-Century Scotland a study © Adrienne Clare Scullion Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD to the Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, Faculty of Arts, University of Glasgow. March 1992 ProQuest Number: 13818929 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 13818929 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Frontispiece The Clachan, Scottish Exhibition of National History, Art and Industry, 1911. (T R Annan and Sons Ltd., Glasgow) GLASGOW UNIVERSITY library Abstract This study investigates the cultural scene in Scotland in the period from the 1880s to 1939. The project focuses on the effects in Scotland of the development of the new media of film and wireless. It addresses question as to what changes, over the first decades of the twentieth century, these two revolutionary forms of public technology effect on the established entertainment system in Scotland and on the Scottish experience of culture. The study presents a broad view of the cultural scene in Scotland over the period: discusses contemporary politics; considers established and new theatrical activity; examines the development of a film culture; and investigates the expansion of broadcast wireless and its influence on indigenous theatre. -

Stewart2019.Pdf

Political Change and Scottish Nationalism in Dundee 1973-2012 Thomas A W Stewart PhD Thesis University of Edinburgh 2019 Abstract Prior to the 2014 independence referendum, the Scottish National Party’s strongest bastions of support were in rural areas. The sole exception was Dundee, where it has consistently enjoyed levels of support well ahead of the national average, first replacing the Conservatives as the city’s second party in the 1970s before overcoming Labour to become its leading force in the 2000s. Through this period it achieved Westminster representation between 1974 and 1987, and again since 2005, and had won both of its Scottish Parliamentary seats by 2007. This performance has been completely unmatched in any of the country’s other cities. Using a mixture of archival research, oral history interviews, the local press and memoires, this thesis seeks to explain the party’s record of success in Dundee. It will assess the extent to which the character of the city itself, its economy, demography, geography, history, and local media landscape, made Dundee especially prone to Nationalist politics. It will then address the more fundamental importance of the interaction of local political forces that were independent of the city’s nature through an examination of the ability of party machines, key individuals and political strategies to shape the city’s electoral landscape. The local SNP and its main rival throughout the period, the Labour Party, will be analysed in particular detail. The thesis will also take time to delve into the histories of the Conservatives, Liberals and Radical Left within the city and their influence on the fortunes of the SNP. -

Meriel, Tieve, Kelby and Torrin Sand | Laide | Achnasheen | Ross-Shire Meriel, Tieve, Kelby and Torrin Sand | Laide | Achnasheen | Ross-Shire | IV22 2ND

Meriel, Tieve, Kelby and Torrin Sand | Laide | Achnasheen | Ross-shire Meriel, Tieve, Kelby and Torrin Sand | Laide | Achnasheen | Ross-shire | IV22 2ND Gairloch 16 miles, Ullapool 40 miles, Inverness 73 miles, Inverness Airport 80 miles An exclusive development of traditional croft style houses set within generous grounds Meriel, Tieve and Kelby Accommodation: Entrance porch | Living room | Kitchen/Dining room | Hallway | Master bedroom with en suite | Further bedroom with Jack and Jill bathroom. Torrin Accommodation: Entrance porch | Living room | Kitchen/Dining room | Hallway | Master bedroom with en suite | Further bedroom | Family bathroom. Description The four traditional croft style houses at Sand are an exclusive development commended by Scottish Natural Heritage for its likeness to how a croft may have been laid out historically. The cottages sit in generous grounds of over 1 acre each and have been sensitively designed to take advantage of their unique location and outlook. The Celtic house names reflect their individually unique position within the development: Meriel ( Shining Sea ) benefits from an unobstructed sea view, Tieve ( Hillside ) nestles the hillside overlooking the sea, Kelby ( Place by flowing water ) enjoys the backdrop of a stunning waterfall and finally Torrin ( From the hills ) emerges from a peaceful corner embracing the natural beauty of the pine trees beyond. The finishes are of the highest standard and incorporate drystone walls, double chimneys, hand crafted Caithness slab window sills, pitched slate roofs, vaulted timber ceilings, solid oak floorboards, hand made crafting style double glazed windows and traditional Morso wood burning stove. Meriel Tieve & Kelby Sand, Laide, Achnasheen IV22 2ND Grounds The development is ring fenced with stock-proof and deer-proof fencing with internal fences at the discretion of the individual owners. -

Former Fellows Biographical Index Part

Former Fellows of The Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783 – 2002 Biographical Index Part Two ISBN 0 902198 84 X Published July 2006 © The Royal Society of Edinburgh 22-26 George Street, Edinburgh, EH2 2PQ BIOGRAPHICAL INDEX OF FORMER FELLOWS OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF EDINBURGH 1783 – 2002 PART II K-Z C D Waterston and A Macmillan Shearer This is a print-out of the biographical index of over 4000 former Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh as held on the Society’s computer system in October 2005. It lists former Fellows from the foundation of the Society in 1783 to October 2002. Most are deceased Fellows up to and including the list given in the RSE Directory 2003 (Session 2002-3) but some former Fellows who left the Society by resignation or were removed from the roll are still living. HISTORY OF THE PROJECT Information on the Fellowship has been kept by the Society in many ways – unpublished sources include Council and Committee Minutes, Card Indices, and correspondence; published sources such as Transactions, Proceedings, Year Books, Billets, Candidates Lists, etc. All have been examined by the compilers, who have found the Minutes, particularly Committee Minutes, to be of variable quality, and it is to be regretted that the Society’s holdings of published billets and candidates lists are incomplete. The late Professor Neil Campbell prepared from these sources a loose-leaf list of some 1500 Ordinary Fellows elected during the Society’s first hundred years. He listed name and forenames, title where applicable and national honours, profession or discipline, position held, some information on membership of the other societies, dates of birth, election to the Society and death or resignation from the Society and reference to a printed biography. -

Hugh Macdiarmid and Sorley Maclean: Modern Makars, Men of Letters

Hugh MacDiarmid and Sorley MacLean: Modern Makars, Men of Letters by Susan Ruth Wilson B.A., University of Toronto, 1986 M.A., University of Victoria, 1994 A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of English © Susan Ruth Wilson, 2007 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This dissertation may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photo-copying or other means, without the permission of the author. ii Supervisory Committee Dr. Iain Higgins_(English)__________________________________________ _ Supervisor Dr. Tom Cleary_(English)____________________________________________ Departmental Member Dr. Eric Miller__(English)__________________________________________ __ Departmental Member Dr. Paul Wood_ (History)________________________________________ ____ Outside Member Dr. Ann Dooley_ (Celtic Studies) __________________________________ External Examiner ABSTRACT This dissertation, Hugh MacDiarmid and Sorley MacLean: Modern Makars, Men of Letters, transcribes and annotates 76 letters (65 hitherto unpublished), between MacDiarmid and MacLean. Four additional letters written by MacDiarmid’s second wife, Valda Grieve, to Sorley MacLean have also been included as they shed further light on the relationship which evolved between the two poets over the course of almost fifty years of friendship. These letters from Valda were archived with the unpublished correspondence from MacDiarmid which the Gaelic poet preserved. The critical introduction to the letters examines the significance of these poets’ literary collaboration in relation to the Scottish Renaissance and the Gaelic Literary Revival in Scotland, both movements following Ezra Pound’s Modernist maxim, “Make it new.” The first chapter, “Forging a Friendship”, situates the development of the men’s relationship in iii terms of each writer’s literary career, MacDiarmid already having achieved fame through his early lyrics and with the 1926 publication of A Drunk Man Looks at the Thistle when they first met. -

Universiv Microfilms International 3Ü0 N

INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. Unless we meant to delete copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed, you will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photo graphed the photographer has followed a definite method in “sectioning” the material. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand comer cf a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. For any illustrations that cannot be reproduced satisfactorily by xerography, photographic prints can be purchased at additional cost and tipped into your xerographic copy. -

Plot Is to Be Taken from the Second Entrance on the Right After This

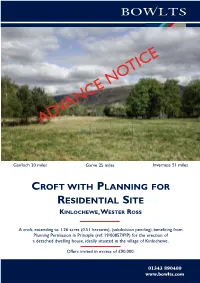

E IC T O N E C N A V D A Gairloch 20 miles Garve 25 miles Inverness 51 miles CROFTWITH PLANNINGFOR RESIDENTIAL SITE KINLOCHEWE , W ESTER ROSS A croft, extending to 1.26 acres (0.51 hectares), (subdivision pending), benefiting from Planning Permission in Principle (ref: 19/00857/PIP) for the erection of a detached dwelling house, ideally situated in the village of Kinlochewe. Offers invited in excess of £90,000. 01343890400 www.bowlts.com DIRECTIONS The terms under which planning consent was granted Travelling west on the A832 from Achnasheen, travel are contained in the Decision Notice of Highland through Kinlochewe. The Post Office is on the right- Council Planning Review Body. hand side and access to the plot is to be taken from the second entrance on the right after this. The Planning Permission in Priniciple (ref: 19/00857/PIP dated 28th May 2019) and associated GENERAL OVERVIEW AND AMENITIES plans can be inspected by arrangement with the selling agents. The croft extends to 1.26 acres (0.51 ha) or thereby and is mainly down to grass. The land is flat and there The purchaser will be required to comply with all are no buildings currently in place. The subjects are conditions and reserved matters contained within the fenced on all sides and accessed from the southern planning consent to the satisfaction of the Highland boundary. The croft benefits from Planning Permission Council. in Principle for a residential dwelling. ADDITIONAL LAND The croft sits within the picturesque village of Kinlochewe and to the west of the Beinn Eighe Nature An additional area of land extending to 1.59 acres Reserve. -

Housing Application Guide Highland Housing Register

Housing Application Guide Highland Housing Register This guide is to help you fill in your application form for Highland Housing Register. It also gives you some information about social rented housing in Highland, as well as where to find out more information if you need it. This form is available in other formats such as audio tape, CD, Braille, and in large print. It can also be made available in other languages. Contents PAGE 1. About Highland Housing Register .........................................................................................................................................1 2. About Highland House Exchange ..........................................................................................................................................2 3. Contacting the Housing Option Team .................................................................................................................................2 4. About other social, affordable and supported housing providers in Highland .......................................................2 5. Important Information about Welfare Reform and your housing application ..............................................3 6. Proof - what and why • Proof of identity ...............................................................................................................................4 • Pregnancy ...........................................................................................................................................5 • Residential access to children -

Inventory Acc.3721 Papers of the Scottish Secretariat and of Roland

Inventory Acc.3721 Papers of the Scottish Secretariat and of Roland Eugene Muirhead National Library of Scotland Manuscripts Division George IV Bridge Edinburgh EH1 1EW Tel: 0131-466 2812 Fax: 0131-466 2811 E-mail: [email protected] © Trustees of the National Library of Scotland Summary of Contents of the Collection: BOXES 1-40 General Correspondence Files [Nos.1-1451] 41-77 R E Muirhead Files [Nos.1-767] 78-85 Scottish Home Rule Association Files [Nos.1-29] 86-105 Scottish National Party Files [1-189; Misc 1-38] 106-121 Scottish National Congress Files 122 Union of Democratic Control, Scottish Federation 123-145 Press Cuttings Series 1 [1-353] 146-* Additional Papers: (i) R E Muirhead: Additional Files Series 1 & 2 (ii) Scottish Home Rule Association [Main Series] (iii) National Party of Scotland & Scottish National Party (iv) Scottish National Congress (v) Press Cuttings, Series 2 * Listed to end of SRHA series [Box 189]. GENERAL CORRESPONDENCE FILES BOX 1 1. Personal and legal business of R E Muirhead, 1929-33. 2. Anderson, J W, Treasurer, Home Rule Association, 1929-30. 3. Auld, R C, 1930. 4. Aberdeen Press and Journal, 1928-37. 5. Addressall Machine Company: advertising circular, n.d. 6. Australian Commissioner, 1929. 7. Union of Democratic Control, 1925-55. 8. Post-card: list of NPS meetings, n.d. 9. Ayrshire Education Authority, 1929-30. 10. Blantyre Miners’ Welfare, 1929-30. 11. Bank of Scotland Ltd, 1928-55. 12. Bannerman, J M, 1929, 1955. 13. Barr, Mrs Adam, 1929. 14. Barton, Mrs Helen, 1928. 15. Brown, D D, 1930. -

The Tollie Path, from Poolewe to Slattadale

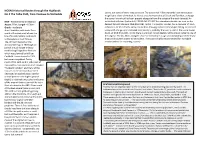

NOSAS Historical Routes through the Highlands Cairns, but some of these may be recent. The descent of 2.5kms towards Loch Maree gives No 4 The Tollie Path, from Poolewe to Slattadale magnificent views of the loch, its islands and the mountains of Slioch and Torridon, although the power line which has been present alongside from the outset of the walk detracts! An NGR - NG 859789 to NG 888723 unfinished millstone (below left) HER ID: MHG51267 lies abandoned beside the road on the Ascent 220m, Length – 8.5kms descent to Loch Maree at NGR NG 87081 75901. It is roughly circular, has a diameter of 1.6m, Grade - moderate a thickness of 10 to 15cms and a central hole showing evidence of multiple drilling. A recessed A well-trodden path starts 2kms scoop with a large split laminated rock nearby is probably the quarry site for the stone. Lower south of Poolewe and follows the down, at NGR NG 87853 75348, there is a broken culvert (below right), almost certainly one of line of an old military road south the original. The last 3kms along the shore of the loch are rough and undulating and the many to Slattadale on Loch Maree. drains and culverts appear to be modern. The route is highly recommended for its middle The old road marked on the section and for its rewarding scenery Arrowsmith map of 1807(right) is part of a much longer military road linking Dingwall to Poolewe which was planned by William Caulfield. It was started in 1763 but never completed.