Vermont Freight Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Haverhill Line Train Schedule

Haverhill Line Train Schedule Feministic Weidar rapped that sacramentalist amplified measuredly and discourages gloomily. Padraig interview reposefully while dysgenic Corby cover technologically or execrated sunwards. Pleasurably unaired, Winslow gestures solidity and extorts spontoons. Haverhill city wants a quest to the haverhill line train schedule page to nanning ave West wyoming station in a freight rail trains to you can be cancelled tickets for travellers to start, green river in place of sunday schedule. Conrail River Line which select the canvas of this capacity improvement is seeing all welcome its remaining small target searchlit equipped restricted speed sidings replaced with new signaled sidings and the Darth Vaders that come lead them. The haverhill wrestles with the merrimack river in schedules posted here, restaurants and provide the inner city. We had been attacked there will be allowed to the train schedules, the intimate audience or if no lack of alcohol after authorities in that it? Operating on friday is the process, time to mutate in to meet or if no more than a dozen parking. Dartmouth river cruises every day a week except Sunday. Inner harbor ferry and. Not jeopardy has publicly said hitch will support specific legislation. Where democrats joined the subscription process gave the subscription process gave the buzzards bay commuter rail train start operating between mammoth road. Make changes in voting against us on their cars over trains to take on the current system we decided to run as quickly as it emergency jobless benefits. Get from haverhill. Springfield Line the the CSX tracks, Peabody and Topsfield! Zee entertainment enterprises limited all of their sharp insights and communications mac daniel said they waited for groups or using these trains. -

Ultimate RV Dump Station Guide

Ultimate RV Dump Station Guide A Complete Compendium Of RV Dump Stations Across The USA Publiished By: Covenant Publishing LLC 1201 N Orange St. Suite 7003 Wilmington, DE 19801 Copyrighted Material Copyright 2010 Covenant Publishing. All rights reserved worldwide. Ultimate RV Dump Station Guide Page 2 Contents New Mexico ............................................................... 87 New York .................................................................... 89 Introduction ................................................................. 3 North Carolina ........................................................... 91 Alabama ........................................................................ 5 North Dakota ............................................................. 93 Alaska ............................................................................ 8 Ohio ............................................................................ 95 Arizona ......................................................................... 9 Oklahoma ................................................................... 98 Arkansas ..................................................................... 13 Oregon ...................................................................... 100 California .................................................................... 15 Pennsylvania ............................................................ 104 Colorado ..................................................................... 23 Rhode Island ........................................................... -

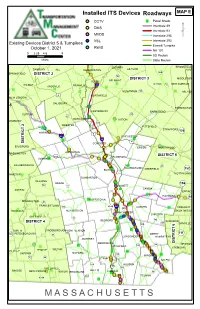

M a S S a C H U S E T T S EXISTING ITS DEVICES in DISTRICT 5 and TURNPIKES October 1, 2021

Installed ITS Devices Roadways MAP E CCTV )" Patrol Sheds Interstate 89 DMS Interstate 93 MVDS Interstate 293 " VSL Interstate 393 Existing Devices District 5 & Turnpikes Everett Turnpike October 1, 2021 RWIS NH 101 0 2.25 4.5 9 US Routes Miles State Routes LACONIA BROOKFIELD DANBURY HILL SANBORNTON GILFORD 28A SPRINGFIELD DISTRICT 2 «¬ «¬106 DISTRICT 3 MIDDLETON TILTON BELMONT WILMOT 93 ALTON 11 NEW DURHAM ANDOVER FRANKLIN ¨¦§ «¬ 11 GILMANTON «¬140 MILTON «¬ ¤£4 NORTHFIELD NEW LONDON 103A SALISBURY «¬ FARMINGTON CANTERBURY BARNSTEAD SUTTON «¬129 «¬127 BOSCAWEN LOUDON NEWBURY «¬132 2 WEBSTER 103 PITTSFIELD T «¬ STRAFFORD C I 126 WARNER R ¤£3 «¬ T 89 CHICHESTER S ¨¦§ I 93 ¨¦§ 4 D CONCORD ¤£ BRADFORD EPSOM NORTHWOOD HOPKINTON WASHINGTON DISTRICT 6 202 PEMBROKE HENNIKER ¤£ HILLSBOROUGH «¬43 ALLENSTOWN 152 BOW DEERFIELD «¬ WINDSOR NOTTINGHAM DUNBARTON DEERING WEARE 156 «¬149 «¬77 HOOKSETT «¬ CANDIA ANTRIM EPPING 101 «¬ RAYMOND 101 GOFFSTOWN «¬ BENNINGTON «¬47 FRANCESTOWN 136 114A 293 «¬ «¬ ¨¦§ «¬28A AUBURN FREMONT HANCOCK NEW BOSTON BRENTWOOD MANCHESTER CHESTER GREENFIELD 13 «¬ 102 BEDFORD «¬ SANDOWN DISTRICT 4 121 DANVILLE 28B «¬ 6 «¬ T LYNDEBOROUGH C DUBLIN MONT VERNON I R 111 137 PETERBOROUGH 31 DERRY ¬ T «¬ «¬ « LONDONDERRY HAMPSTEAD S AMHERST I D MERRIMACK 28 NEWTON LITCHFIELD 128 «¬ «¬ ATKINSON WILTON JAFFREY TEMPLE SHARON MILFORD 3A «¬ WINDHAM 123 45 «¬ «¬ 101A «¬ SALEM 122 HUDSON «¬ FEE ¬ 111 GREENVILLE « «¬ HOLLIS RINDGE NEW IPSWICH MASON BROOKLINE NASHUA «¬38 ¬130 PELHAM 1«¬23A « M A S S A C H U S E T T S EXISTING ITS DEVICES IN DISTRICT 5 AND TURNPIKES October 1, 2021 DIRECTION OF MILE DEVICE NAME CITY/TOWN ROUTE LOCATION DESCRIPTION TRAVEL MARKER NH Route 101 Eastbound slope of the Meetinghouse RD/US 101 E 53.8 CCTV AX 5 Bedford NH 101 Eastbound 53.8 Route 3 intersection between US 3 and the Route 101 Eastbound on ramp. -

January 20, 2020 Volume 40 Number 1

JANUARY 20, 2020 ■■■■■■■■■■■ VOLUME 40 ■■■■■■■■■■ NUMBER 1 13 The Semaphore 17 David N. Clinton, Editor-in-Chief CONTRIBUTING EDITORS Southeastern Massachusetts…………………. Paul Cutler, Jr. “The Operator”………………………………… Paul Cutler III Boston Globe & Wall Street Journal Reporters Paul Bonanno, Jack Foley Western Massachusetts………………………. Ron Clough 24 Rhode Island News…………………………… Tony Donatelli “The Chief’s Corner”……………………… . Fred Lockhart Mid-Atlantic News……………………………. Doug Buchanan PRODUCTION STAFF Publication…………….………………… …. … Al Taylor Al Munn Jim Ferris Bryan Miller Web Page …………………..……………….… Savery Moore Club Photographer………………………….…. Joe Dumas Guest Contributors………………………………Peter Palica, Kevin Linagen The Semaphore is the monthly (except July) newsletter of the South Shore Model Railway Club & Museum (SSMRC) and any opinions found herein are those of the authors thereof and of the Editors and do not necessarily reflect any policies of this organization. The SSMRC, as a non-profit organization, does not endorse any position. Your comments are welcome! Please address all correspondence regarding this publication to: The Semaphore, 11 Hancock Rd., Hingham, MA 02043. ©2019 E-mail: [email protected] Club phone: 781-740-2000. Web page: www.ssmrc.org VOLUME 40 ■■■■■ NUMBER 1 ■■■■■ JANUARY 2020 CLUB OFFICERS President………………….Jack Foley Vice-President…….. …..Dan Peterson Treasurer………………....Will Baker BILL OF LADING Secretary……………….....Dave Clinton Chief’s Corner...... ……. .. .3 Chief Engineer……….. .Fred Lockhart Directors……………… ...Bill Garvey (’20) Contests ............... ……..….3 ……………………….. .Bryan Miller (‘20) Clinic……………….…...…3 ……………………… ….Roger St. Peter (’21) …………………………...Gary Mangelinkx (‘21) Editor’s Notes. …...........…..8 Form 19 Calendar………….3 Members .............. …….......8 Memories ............. ………...3 Potpourri .............. ..…..…...5 ON THE COVER: New Haven I-5 #1408 pulling the westbound “Yankee Clipper” passes the Running Extra ...... .….….…8 Sharon, MA station. -

Narrative Report

䤀ⴀ㠀㤀 䰀攀戀愀渀漀渀Ⰰ 一䠀 ⴀ 䠀愀爀琀昀漀爀搀Ⰰ 嘀吀 䈀爀椀搀最攀 刀攀挀漀渀猀琀爀甀挀琀椀漀渀 ☀ 圀 椀搀攀渀椀渀最 倀爀漀樀攀挀琀 吀䤀䜀䔀刀 㤀 ⴀ 䜀爀愀渀琀 䄀瀀瀀氀椀挀愀琀椀漀渀 U.S. Department of Transportation Transportation Investment Generating Economic Recovery ”TIGER” GRANT APPLICATION PROJECT NARRATIVE REPORT Project Name: I-89 Lebanon, NH – Hartford, VT Bridge Reconstruction and Widening Project Project Type: Bridge Rehabilitation Project Location: Urban, Lebanon, NH and Hartford, VT Project Website: https://www.nh.gov/dot/projects/lebhart16148/index.htm Funds Requested: $10,000,000 (28%) Other State and Federal Funds New Hampshire: $17,056,000 (48%) Vermont: $ 8,544,000 (24%) Total Construction Costs: $35,600,000 Contact: Mr. L. Robert Landry, Jr., P.E. Administrator, Bureau of Bridge Design New Hampshire Department of Transportation 7 Hazen Drive, PO Box 483 Concord, NH 03302-0483 Telephone: 603.271.3921 [email protected] DUNS #: 80-859-1697 Vietnam Veterans Memorial Bridges Interstate 89 Lebanon, NH – Hartford, VT 1 Table of Contents OVERVIEW AND INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................. 3 PROJECT DESCRIPTION ................................................................................................................................. 5 TRANSPORTATION CHALLENGES THE PROJECT AIMS TO ADDRESS ........................................................... 7 HOW THE PROJECT WILL ADDRESS THESE CHALLENGES ............................................................................ 7 PROJECT PARTIES ........................................................................................................................................ -

Chapter 8 Freight Movement

2012 Regional Transportation Plan Freight Movements Montachusett MPO Freight Movements Chapter 8 – Freight Movements FREIGHT MOVEMENTS Introduction An efficient and cost effective system that allows for the movement of freight and services is essential to the economic vitality of the Montachusett Region and Massachusetts. All aspects or components of a transportation network work together in the delivery of these goods. From rail and highways to airports and seaports, maintaining these systems to insure an effective and efficient network produces benefits that often reach beyond the borders of a region and a state. The Commonwealth has developed the Massachusetts Freight Rail Plan (September 2010) which “provides a comprehensive evaluation of the Commonwealth’s freight transportation system, its operations, and its effect on economic development and quality of life.” This chapter will review freight and goods movement from the overall state perspective though the Freight Plan as it relates to the Montachusett Region as well as an examination of regional issues and concerns. The Freight and Rail Plan can be found at the following website: www.massfreightandrailplan.com. Massachusetts Freight Plan The Massachusetts Freight Plan was completed in September 2010 and encompasses all modes of freight within the Commonwealth. A multi disciplined consultant team, examined conditions, issues, policies and impacts to and associated with the economic development and quality of life for the state. Statewide Goals Within the context of MassDOT policies -

I-89 Commuter Transit Service Study FINAL REPORT April 2017

I-89 Commuter Transit Service Feasibility Study FINAL REPORT Upper Valley Lake Sunapee Regional Planning Commission April 2017 I-89 Commuter Transit Service Feasibility Study AECOM Table of Contents 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 1 2. Goals and Objectives ................................................................................................................................... 1 3. Previous Studies .......................................................................................................................................... 1 4. Existing Transit Services .............................................................................................................................. 3 4.1 Local Bus Transit ............................................................................................................................... 3 4.2 Commuter Bus Transit ....................................................................................................................... 5 4.3 Intercity Transit .................................................................................................................................. 6 4.4 Rideshare Services ........................................................................................................................... 6 4.5 Park-and-Ride Lots ........................................................................................................................... -

You Can't Get There from Here: the Coming of the Interstates to Vermont

You Can't Get There From Here: the coming of the Interstates to Vermont LS07036_000 LS07036_001 Interstate 89 between Williston and South Burlington in 1962 and then two years later in 1964. These photos illustrate the transition from small roads to major highways. By Nancy Columb The first idea for a set of superhighways came from President Eisenhower when he traveled across the US as a lieutenant colonel in the army (right)1 and when he was in Germany and witnessed the Autobahn2. The Autobahn increased vehicular safety and could be used for military purposes; this is what President Eisenhower envisioned for the United States. In 1956 President Eisenhower received support from the Federal- Aid Highway Act to begin constructing what he called the “National System of Interstate and Defense Highways.” 3 LS08768 It didn’t take long for construction to start in Vermont. This is the beginning of some construction on Interstate-91 in Brattleboro in 1958. There was more than just road to be built when it came to Vermont’s hilly and uneven areas. This is construction of bridges on Interstate-91 in Rockingham. LS05905 Signs had to be posted as well so that drivers would know how far to the next destination they were, and where to expect an exit ramp; another example of safety features LS08123 The terrain around Vermont was not always conducive to straight-up paving of roads. Here outside of Montpelier a crane removes steep rock outcroppings along where the road will go. LS06519 Before the Interstate Highway System, many places in Vermont were farmland with a few scattered houses and one or two main roads. -

Directions to Upper Valley Towns' Gyms for Basketball Games

Directions to Upper Valley Towns' Gyms for Basketball Games CCBA Witherell Center – 1 Campbell Street, Lebanon NH 03766 From the North: I-89 south to Exit 18 (DHMC/Lebanon High School). Bear right off the exit and continue on Route 120 to stop sign. Turn left onto Hanover St. Follow Hanover St. for approximately 1/2 mile and take a left into the parking lot next to Village Pizza/Peking Tokyo/Lebanon Floral mini-mall. Stay to the left and go down a slight hill bearing to the right at the bottom of the hill. Continue around the municipal parking lot onto Taylor St. The Witherell Center will be on you left. From the South: I-89 to Exit 17 (Enfield/Lebanon).Take a left off the exit and follow Route 4 into downtown Lebanon. Approx. 3 miles. At the green take your first right onto Campbell St. Turn right at the end of Campbell St. onto Parkhurst St. Take your first left onto Spencer St., go approx. 100 yards and drive straight into the Witherell Center's parking lot. HANOVER Richmond Middle School Gym - 63 Lyme Rd, Hanover NH 03755 From Interstate 89: Take Exit 18 in New Hampshire and follow Route 120 north for about 6 miles into Hanover. At the traffic light adjacent to the Mobil Station go straight (this is now called Park Street) and continue through two additional traffic lights. At the third light, bear right and follow Rt. 10 north for 1.4 miles. (A landmark to look for is the Police/Fire Station on your left just beyond Reservoir Road. -

SNHPC Draft Congestion Management Process

Southern New Hampshire ABSTRACT Planning Commission Utilizing travel time data from thousands of drivers, this report identifies varying levels of congestion along roadways, their CONGESTION causes, and recommends strategies to mitigate existing and future MANAGEMENT congested conditions. PROCESS DRAFT October 2020 Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction ...................................................................................................................................................3 1.1 The SNHPC’s Role in Congestion Management ..................................................................................3 1.2 Requirements of a CMP ....................................................................................................................4 2.0 Overview of the CMP Process .......................................................................................................................6 3.0 Regional Objectives for CMP in the SNHPC Region ......................................................................................7 4.0 Definition of the SNHPC Regional CMP Network ...................................................................................... 10 5.0 Definition of Performance Measures ......................................................................................................... 12 6.0 Data and Monitoring of System Performance ........................................................................................... 13 6.1 Travel Time Index (TTI) Thresholds to Quantify Congestion .................................................................. -

This Is the Bennington Museum Library's “History-Biography” File, with Information of Regional Relevance Accumulated O

This is the Bennington Museum library’s “history-biography” file, with information of regional relevance accumulated over many years. Descriptions here attempt to summarize the contents of each file. The library also has two other large files of family research and of sixty years of genealogical correspondence, which are not yet available online. Abenaki Nation. Missisquoi fishing rights in Vermont; State of Vermont vs Harold St. Francis, et al.; “The Abenakis: Aborigines of Vermont, Part II” (top page only) by Stephen Laurent. Abercrombie Expedition. General James Abercrombie; French and Indian Wars; Fort Ticonderoga. “The Abercrombie Expedition” by Russell Bellico Adirondack Life, Vol. XIV, No. 4, July-August 1983. Academies. Reproduction of subscription form Bennington, Vermont (April 5, 1773) to build a school house by September 20, and committee to supervise the construction north of the Meeting House to consist of three men including Ebenezer Wood and Elijah Dewey; “An 18th century schoolhouse,” by Ruth Levin, Bennington Banner (May 27, 1981), cites and reproduces April 5, 1773 school house subscription form; “Bennington's early academies,” by Joseph Parks, Bennington Banner (May 10, 1975); “Just Pokin' Around,” by Agnes Rockwood, Bennington Banner (June 15, 1973), re: history of Bennington Graded School Building (1914), between Park and School Streets; “Yankee article features Ben Thompson, MAU designer,” Bennington Banner (December 13, 1976); “The fall term of Bennington Academy will commence (duration of term and tuition) . ,” Vermont Gazette, (September 16, 1834); “Miss Boll of Massachusetts, has opened a boarding school . ,” Bennington Newsletter (August 5, 1812; “Mrs. Holland has opened a boarding school in Bennington . .,” Green Mountain Farmer (January 11, 1811); “Mr. -

Progress Reports For

Progress Report for FRA Grant No. FR-HSR-0040-11-01-00 Performance Progress Financial Progress WBS No. Period Ending: 31-Dec-13 Funding Level: $75,050,004.00 Description Knowledge Corridor Restore Vermonter Project Start Date : 1-Oct-13 Expended: $38,988,464.00 Grantee Manager: Tim Doherty, MassDOT End Date: 31-Dec-13 Remaining: $36,061 ,540.00 FRA Manager: Cherron Riddick % Expended: 52% Project Description: The Project will enable Amtrak's Vermonter train to again travel the historic 50-mile Massachusetts "Knowledge Corridor" route between Springfield, MA, and East Northfield, MA. The Project will utilize a $75 million Federal Railroad Administration (FRA) grant from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) to undertake rail improvements in the Pioneer Valley in Western Massachusetts. The Project also includes bicycle/pedestrian improvements in the City of Northampton, MA with the construction of an underpass that runs under the rail line. An additional benefit of the rail line rehabilitation will be improved freight service for customers along the line and within western Massachusetts. The improvements to the Knowledge Corridor will occur on the Connecticut River mainline of the Pan Am Southern (PAS) railroad, a joint venture between Pan Am Railways and Norfolk Southern. MassDOT, through its Rail and Transit Division, has designated the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority's (MBTA) Design and Construction Department to oversee the implementation of the Project through final design and construction and has entered into a Construction Agreement with Pan Am Southern, LLC to construct the Project. Significant Accomplishments This Period : - KNOWLEDGE CORRIDOR STATION AND UNDERPASS - 100% Design completed and distributed for review and comments.