New Hampshire Turnpike System Traffic and Revenue Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Final Point of Access Study

Prepared for: I-95/Scudder Falls Bridge Improvement Project Technical Memorandum No. 28 FINAL POINT OF ACCESS STUDY Contract C-393A, Capital Project No. CP0301A Prepared by: Philadelphia, PA In association with: HNTB Corporation STV Inc. Gannett Fleming, Inc. A.D. Marble & Company Kise Straw & Kolodner, Inc. Riverfront Associates, Inc. November, 2012 1 2 Technical Memorandum No. 28 – Final Point of Access Study Contract C-393A, Capital Project No. CP0301A I-95/Scudder Falls Bridge Improvement Project TABLE OF CONTENTS A. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY, INTRODUCTION AMD REQUIREMENTS ... 1 I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................ 1 Purpose of Access......................................................................... 1 Summary of Findings .................................................................... 2 II. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................. 7 Project Description .............................................................. 7 Study Area Description ........................................................ 7 Project Area Description .................................................... 10 Project Purpose and Need .................................................. 11 III. REQUIREMENTS FOR APPROVAL OF ACCESS ..................................... 12 B. ENGINEERING STUDY ............................................................. 17 I. CURRENT CONDITIONS ........................................................... 17 Roadway Network -

Ultimate RV Dump Station Guide

Ultimate RV Dump Station Guide A Complete Compendium Of RV Dump Stations Across The USA Publiished By: Covenant Publishing LLC 1201 N Orange St. Suite 7003 Wilmington, DE 19801 Copyrighted Material Copyright 2010 Covenant Publishing. All rights reserved worldwide. Ultimate RV Dump Station Guide Page 2 Contents New Mexico ............................................................... 87 New York .................................................................... 89 Introduction ................................................................. 3 North Carolina ........................................................... 91 Alabama ........................................................................ 5 North Dakota ............................................................. 93 Alaska ............................................................................ 8 Ohio ............................................................................ 95 Arizona ......................................................................... 9 Oklahoma ................................................................... 98 Arkansas ..................................................................... 13 Oregon ...................................................................... 100 California .................................................................... 15 Pennsylvania ............................................................ 104 Colorado ..................................................................... 23 Rhode Island ........................................................... -

Community Guide

ROCHESTERNH.ORG GREATER ROCHESTER CHAMBER OF COMMERCE 2016 • 1 It’s about People. 7HFKQRORJ\ 7UXVW frisbiehospital.com People are the foundation of what health that promotes faster healing, better health, care is about. People like you who are and higher quality of life. looking for the best care possible—and It’s this approach that has allowed us to people like the professionals at Frisbie develop trust with our patients, and to Memorial Hospital who are dedicated to become top-rated nationally for our quality providing it. of care and services. :HXVHWKHODWHVWWHFKQRORJ\WRKHOSÀQG VROXWLRQVWKDWEHQHÀWSDWLHQWV7HFKQRORJ\ 11 Whitehall Road, Rochester, NH 03867 | Phone (603) 332-5211 2 • 2016 GREATER ROCHESTER CHAMBER OF COMMERCE ROCHESTERNH.ORG contents Editor: 4 A Message from the Chamber Greater Rochester Chamber of Commerce 5 City of Rochester Welcome 6 New Hampshire Economic Development Photography Compliments of: 7 New Hampshire & Rochester Facts Cornerstone VNA Frisbie Memorial Hospital 8 Rochester – Ideal Destination, Convenient Location Great Bay Community College 10 Rochester History Greater Rochester Chamber of Commerce Revolution Taproom & Grill 11 Arts, Culture & Entertainment Rochester Economic Development 13 Rochester Business & Industry Rochester Fire Department A Growing & Diverse Economy Rochester Historical Society Rochester Main Street 14 Rochester Growth & Development Rochester Opera House Business & Industrial Parks Rochester Police Department 15 Rochester Commercial Districts Produced by: 16 Helpful Information Rochester -

7-ELEVEN (S&P: AA-) 117 Queen City Avenue Manchester, NH 03101

NET LEASE INVESTMENT OFFERING 7-ELEVEN (S&P: AA-) 117 Queen City Avenue Manchester, NH 03101 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Executive Summary II. Location Overview III. Market & Tenant Overview Executive Summary Site Plan Tenant Profile Investment Highlights Aerial Location Overview Property Overview Maps Demographics Photos NET LEASE INVESTMENT OFFERING DISCLAIMER STATEMENT DISCLAIMER The information contained in the following Offering Memorandum is proprietary and strictly confidential. It is intended STATEMENT: to be reviewed only by the party receiving it from The Boulder Group and should not be made available to any other person or entity without the written consent of The Boulder Group. This Offering Memorandum has been prepared to provide summary, unverified information to prospective purchasers, and to establish only a preliminary level of interest in the subject property. The information contained herein is not a substitute for a thorough due diligence investigation. The Boulder Group has not made any investigation, and makes no warranty or representation. The information contained in this Offering Memorandum has been obtained from sources we believe to be reliable; however, The Boulder Group has not verified, and will not verify, any of the information contained herein, nor has The Boulder Group conducted any investigation regarding these matters and makes no warranty or representation whatsoever regarding the accuracy or completeness of the information provided. All potential buyers must take appropriate measures to verify all of the information set forth herein. NET LEASE INVESTMENT OFFERING EXECUTIVE SUMMARY EXECUTIVE The Boulder Group is pleased to exclusively market for sale a single tenant net leased 7-Eleven property located SUMMARY: within the Manchester, New Hampshire MSA. -

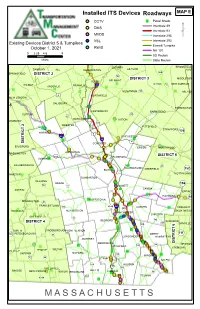

M a S S a C H U S E T T S EXISTING ITS DEVICES in DISTRICT 5 and TURNPIKES October 1, 2021

Installed ITS Devices Roadways MAP E CCTV )" Patrol Sheds Interstate 89 DMS Interstate 93 MVDS Interstate 293 " VSL Interstate 393 Existing Devices District 5 & Turnpikes Everett Turnpike October 1, 2021 RWIS NH 101 0 2.25 4.5 9 US Routes Miles State Routes LACONIA BROOKFIELD DANBURY HILL SANBORNTON GILFORD 28A SPRINGFIELD DISTRICT 2 «¬ «¬106 DISTRICT 3 MIDDLETON TILTON BELMONT WILMOT 93 ALTON 11 NEW DURHAM ANDOVER FRANKLIN ¨¦§ «¬ 11 GILMANTON «¬140 MILTON «¬ ¤£4 NORTHFIELD NEW LONDON 103A SALISBURY «¬ FARMINGTON CANTERBURY BARNSTEAD SUTTON «¬129 «¬127 BOSCAWEN LOUDON NEWBURY «¬132 2 WEBSTER 103 PITTSFIELD T «¬ STRAFFORD C I 126 WARNER R ¤£3 «¬ T 89 CHICHESTER S ¨¦§ I 93 ¨¦§ 4 D CONCORD ¤£ BRADFORD EPSOM NORTHWOOD HOPKINTON WASHINGTON DISTRICT 6 202 PEMBROKE HENNIKER ¤£ HILLSBOROUGH «¬43 ALLENSTOWN 152 BOW DEERFIELD «¬ WINDSOR NOTTINGHAM DUNBARTON DEERING WEARE 156 «¬149 «¬77 HOOKSETT «¬ CANDIA ANTRIM EPPING 101 «¬ RAYMOND 101 GOFFSTOWN «¬ BENNINGTON «¬47 FRANCESTOWN 136 114A 293 «¬ «¬ ¨¦§ «¬28A AUBURN FREMONT HANCOCK NEW BOSTON BRENTWOOD MANCHESTER CHESTER GREENFIELD 13 «¬ 102 BEDFORD «¬ SANDOWN DISTRICT 4 121 DANVILLE 28B «¬ 6 «¬ T LYNDEBOROUGH C DUBLIN MONT VERNON I R 111 137 PETERBOROUGH 31 DERRY ¬ T «¬ «¬ « LONDONDERRY HAMPSTEAD S AMHERST I D MERRIMACK 28 NEWTON LITCHFIELD 128 «¬ «¬ ATKINSON WILTON JAFFREY TEMPLE SHARON MILFORD 3A «¬ WINDHAM 123 45 «¬ «¬ 101A «¬ SALEM 122 HUDSON «¬ FEE ¬ 111 GREENVILLE « «¬ HOLLIS RINDGE NEW IPSWICH MASON BROOKLINE NASHUA «¬38 ¬130 PELHAM 1«¬23A « M A S S A C H U S E T T S EXISTING ITS DEVICES IN DISTRICT 5 AND TURNPIKES October 1, 2021 DIRECTION OF MILE DEVICE NAME CITY/TOWN ROUTE LOCATION DESCRIPTION TRAVEL MARKER NH Route 101 Eastbound slope of the Meetinghouse RD/US 101 E 53.8 CCTV AX 5 Bedford NH 101 Eastbound 53.8 Route 3 intersection between US 3 and the Route 101 Eastbound on ramp. -

Phase II Highway Corridor Strategy Descriptions Technical

ENTRAL ORK OUNTY ONNECTIONS TUDY CENTRAL YORK COUNTY CONNECTIONS STUDY PHASE II HIGHWAY CORRIDOR STRATEGY DESCRIPTIONS PHASE II TECHNICAL MEMORANDUM SEPTEMBER 2011 Prepared for: Maine Department Maine Turnpike Authority of Transportation Prepared by: In association with: Morris Communications • Kevin Hooper Associates T.Y. Lin • Planning Decisions • Facet Decision Systems Dr. Charles Colgan, University of Southern Maine • Evan Richert Normandeau Associates • Preservation Company This document is formatted for two-sided printing. Document II-4 ENTRAL ORK OUNTY ONNECTIONS TUDY CENTRAL YORK COUNTY CONNECTIONS STUDY 1 INTRODUCTION This document summarizes the potential highway corridor improvements – called strategies – that are being tested and evaluated for Phase II of the Central York County Connections Study (CYCCS). Phase II Highway Strategies are a starting point in the development and consideration of candidate improvements for the study; they are not recommendations, nor are they the only strategies that will be studied. Phase II strategies are conceptual in nature, and not yet detailed, specific proposals. Strategies considered later in the study during Phase III, as well as those ultimately recommended by the study, may differ considerably from the initial strategies currently under evaluation in Phase II. Specific aspects of these initially proposed strategies may be dropped, carried forward or combined in different ways, depending on the results of the analyses conducted during Phase II. The study is guided by a Purpose and Need Statement, which articulates that the study is to identify transportation and related land use strategies that enhance economic development opportunities and preserve and improve the regional transportation system. Additional information on the study, including the full Purpose and Need Statement, is available at the project website: www.connectingyorkcounty.org. -

Narrative Report

䤀ⴀ㠀㤀 䰀攀戀愀渀漀渀Ⰰ 一䠀 ⴀ 䠀愀爀琀昀漀爀搀Ⰰ 嘀吀 䈀爀椀搀最攀 刀攀挀漀渀猀琀爀甀挀琀椀漀渀 ☀ 圀 椀搀攀渀椀渀最 倀爀漀樀攀挀琀 吀䤀䜀䔀刀 㤀 ⴀ 䜀爀愀渀琀 䄀瀀瀀氀椀挀愀琀椀漀渀 U.S. Department of Transportation Transportation Investment Generating Economic Recovery ”TIGER” GRANT APPLICATION PROJECT NARRATIVE REPORT Project Name: I-89 Lebanon, NH – Hartford, VT Bridge Reconstruction and Widening Project Project Type: Bridge Rehabilitation Project Location: Urban, Lebanon, NH and Hartford, VT Project Website: https://www.nh.gov/dot/projects/lebhart16148/index.htm Funds Requested: $10,000,000 (28%) Other State and Federal Funds New Hampshire: $17,056,000 (48%) Vermont: $ 8,544,000 (24%) Total Construction Costs: $35,600,000 Contact: Mr. L. Robert Landry, Jr., P.E. Administrator, Bureau of Bridge Design New Hampshire Department of Transportation 7 Hazen Drive, PO Box 483 Concord, NH 03302-0483 Telephone: 603.271.3921 [email protected] DUNS #: 80-859-1697 Vietnam Veterans Memorial Bridges Interstate 89 Lebanon, NH – Hartford, VT 1 Table of Contents OVERVIEW AND INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................. 3 PROJECT DESCRIPTION ................................................................................................................................. 5 TRANSPORTATION CHALLENGES THE PROJECT AIMS TO ADDRESS ........................................................... 7 HOW THE PROJECT WILL ADDRESS THESE CHALLENGES ............................................................................ 7 PROJECT PARTIES ........................................................................................................................................ -

South Norfolk Jordan Bridge (“SNJB”) Is a 5,372 Ft Fixed Bridge That Connects the City of Chesapeake to the City of Portsmouth Over the Elizabeth River In

TOLL REVENUE NEW BUILD / REPLACEMENT SOUTH NORFOLK PRIVATIZATION PRIVATE FINANCING UNSOLICITED BID JORDAN BRIDGE CHESAPEAKE, VA The South Norfolk Jordan Bridge (“SNJB”) is a 5,372 ft fixed bridge that connects the City of Chesapeake to the City of Portsmouth over the Elizabeth River in Virginia. The City of Chesapeake had decommissioned the original Jordan Bridge in November 2008. An unsolicited proposal submitted by United Bridge Partners (“UBP”) to replace the Jordan Bridge with a new, privately owned bridge was approved by the City of Chesapeake in January 20091 by executing an Acquisition and Development Agreement (“ADA”) between UBP and the City of Chesapeake. As part of the ADA, UBP assumed responsibility to demolish the existing Jordan Bridge, aquired the right of way and easments associated with the bridge, and the right to toll, design, construct, finance, operate and assume ownership of a new bridge and associated tolling facilities on the SNJB. The construction of the SNJB was reported to be privately financed. Project revenue on the SNJB comes from tolls, set by the private operator with no defined limit, which are collected electronically on the bridge2. Note: the facts of this case study were reviewed by UBP. We have provided Chesapeake footnotes to describe instances where UBP disputes information in the public domain. BACKGROUND + PROJECT DRIVERS The Elizabeth River Corridor between Midtown Tunnel and High Rise Bridge in southern eastern Virginia near the Chesapeake Bay serves approximately 250,000 Figure 1: Elizabeth River Crossings. vehicle trip crossings per weekday. It is a growing corridor that primarily serves Source: Pickard, A. -

Piscataquog River Management Plan Update

Concord Henniker Hopkinton Map 7 # # Piscataquog River # ?Æ # # Pleasant Stark Management Plan Pond Aä # Pond Bow Weare Reservoir North Branch Piscataquog River # Dudley Dam Hillsborough Pond Dams and 100-Year # ## # ##!# ## ## # Floodplains # # ## # # Weare # Reservoir Everett # # # Lake # # ?§ Dunbarton # #! # # # 100 Year FEMA Floodplain Everett Dam ! # Weare Long Major Dams Deering Pond # # Dams Mt# William Gorham # Pond Pond Hooksett Aa # # Watershed Boundary # # Main Stem Piscataquog River Lakes/Reservoirs Deering # ## # Reservoir # # # # # # Merrimack River Town Boundaries Ferrin Pond # Riverdale Dam Gregg Falls Dam Streams # Daniels Lake # # # # Shattuck # ! Pond Pleasant # Pond Goffstown # Bennington# ## # Middle Branch # # Manchester # # Piscataquog River # # #! Glen Lake# #! # # # # # # Still # # # Beard # # Pond Pond # Hadley Falls Aä # Dennison # # # # Pond Dam # # # # # Dodge ## 0 1 2 3 4 Miles Francestown # Pond # # # # !# # South Branch New Boston # Uncanoonuc # # #Lake # # # Piscataquog River Aû Haunted Data Sources: Lake # NH GRANIT Digital Data (1:24,000) # # # NH Department of Transportation # # # NH Department of Environmental Services # Kelley Falls Dam The individual municipalities represented # on this map and the SNHPC make no # # # representations or guaranties to the accuracy of the features and designations New # of this map. # Bailey # Pond Hampshire # # Map Produced by Greenfield ## # # GIS Service SNHPC 2009. Location # Bedford Contact: [email protected] # # # # Ph: (603) 669-4664 Map This map is for planning -

Toll Roads in the United States: History and Current Policy

TOLL FACILITIES IN THE UNITED STATES Bridges - Roads - Tunnels - Ferries August 2009 Publication No: FHWA-PL-09-00021 Internet: http://www.fhwa.dot.gov/ohim/tollpage.htm Toll Roads in the United States: History and Current Policy History The early settlers who came to America found a land of dense wilderness, interlaced with creeks, rivers, and streams. Within this wilderness was an extensive network of trails, many of which were created by the migration of the buffalo and used by the Native American Indians as hunting and trading routes. These primitive trails were at first crooked and narrow. Over time, the trails were widened, straightened and improved by settlers for use by horse and wagons. These became some of the first roads in the new land. After the American Revolution, the National Government began to realize the importance of westward expansion and trade in the development of the new Nation. As a result, an era of road building began. This period was marked by the development of turnpike companies, our earliest toll roads in the United States. In 1792, the first turnpike was chartered and became known as the Philadelphia and Lancaster Turnpike in Pennsylvania. It was the first road in America covered with a layer of crushed stone. The boom in turnpike construction began, resulting in the incorporation of more than 50 turnpike companies in Connecticut, 67 in New York, and others in Massachusetts and around the country. A notable turnpike, the Boston-Newburyport Turnpike, was 32 miles long and cost approximately $12,500 per mile to construct. As the Nation grew, so did the need for improved roads. -

Advantage MANCHESTER, NEW HAMPSHIRE 2014 REGIONAL GUIDEBOOK

ManchesterAdvantage MANCHESTER, NEW HAMPSHIRE 2014 REGIONAL GUIDEBOOK A New Day for Elm Street The enterprising women leading Manchester’s downtown renaissance Miniature Caring Manchester for Kids The College on An Ideal Dining Commercial Street Experience www.manchester-chamber.org SMALL BUSINESS POWERS THE UNITED STATE OF NEW HAMPSHIRE Since 1926, we’ve been proud to partner with the small businesses that drive New Hampshire’s economy. We know you’re here for the long haul. And so are we. To learn more, visit www.psnh.com. It wasn’t her lucky break, but lucky for you CMC’s Urgent Care offers unscheduled walk-in care for minor illnesses and injuries when you need it most. Urgent Care Quick, convenient, quality care Full team of board certified MD’s, NP’s and PA’s Open 7 days a week, including evenings & weekends On-site laboratory and x-ray specialists Accepted by all insurance providers Just off Interstate 293 in Bedford, NH (5 Washington Place—just north of Macy’s on South River Road) 603.314.4567 CatholicMedicalCenter.org Bellwether Community Credit Union Where Easy Adds Up. Where Easy Adds Up.TM Bellwether Community Credit Union makes it easy for you to get the most out of life and your money with smart options, superior value, and true convenience. Whether it’s depositing a check or closing a loan from home, getting a great rate on your loan, or having access to more than 30,000 free ATMs, choose Bellwether— Where Easy Adds Up. Your savings federally insured to at least $250,000 and backed by the full faith and credit of the United States Government Open to anyone living or working in New Hampshire For more information, visit us at bccu.org. -

Phase 1 Study

DELAWARE RIVER JOINT TOLL BRIDGE COMMISSION SOUTHERLY CROSSINGS CORRIDOR STUDY PHASE I TRANSPORTATION STUDY Prepared for: DELAWARE RIVER JOINT TOLL BRIDGE COMMISSION Prepared by: THE LOUIS BERGER GROUP, INC. EAST ORANGE, NEW JERSEY June 2002 TABLE OF CONTENTS Southerly Crossings Corridor Study TABLE OF CONTENTS Page EXECUTIVE SUMMARY.............................................................Executive Summary Page 1 1.0 INTRODUCTION AND STUDY METHODOLOGY.............................................1-1 1.1 Background.........................................................................................1-1 1.2 Objectives of the Southerly Crossings Corridor Study .....................................1-3 1.3 Traffic Forecasting & Analysis Methodology................................................1-3 1.3.1 Overview.............................................................................................................1-3 1.3.2 Travel Demand Forecasting ................................................................................1-4 1.4 Alternatives Development and Screening .....................................................1-7 1.5 Alternatives Analysis-Measures of Effectiveness .......................................... 1-10 1.5.1 Level of Service...............................................................................................1-10 1.5.2 Construction Cost Estimates............................................................................1-11 2.0 EXISTING CONDITIONS ..............................................................................2-1