MISP) of Reproductive Health Services for Internally Displaced Persons in Kathmandu and Sindhupalchowk Districts, Nepal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Profile 2020/2021 R O GRAM

NVCYE PROGRAM 1 2 0 /2 20 20 Profile l na Natio NVCYE PROGRAM Contact Person: Santoshi Chalise Kalanki -14, Kathmandu, Nepal Tel: +977-15234504 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.icyenepal.org PO Box: 1865 Nepal: An Introduction Official Name: Nepal Population: 35,142,064 (2019 est.,) Official Language: Nepali Currency: Rupees (NPR) Standard Time Zone: UTC+05:45 Capital: Kathmandu Founded in 1768 Government: Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal Current President: Biddhyadevi Bhandari Nepal has 77 department’s (districts), six metropolitan cities (Kathmandu, Janakpur, Biratnagar, Bharatpur, Pokhara and Lalitpur) and 753 new municipalities and rural municipalities. Geography: Nepal is a landlocked country, surrounded by India on three sides and by China's Tibet Autonomous Region to the north. The shape of the country is rectangular with a width of about 650 kilometres and a length of about 200 kilometers. The total landmass is 147,181 square kilometres. Nepal is dependent on India for transit facilities and access to the sea. All the goods and raw materials arrive into Nepal from the Bay of Bengal and through Kolkata. Though small in size, Nepal contains great diversity in landscape. The south of Nepal, which borders India, is flat and known locally as Terai. The Terai is situated about 300 meters above sea level. The landscape then dramatically changes to mid-hills of over 1000 meters and reaches as high as 8000 meters with the Himalayas in the north bordering China. This rise in elevation is punctuated by valleys situated between mountain ranges. Within this maze of mountains, hills, ridges, and low valleys, changes in altitude have resulted in great ecological variations and have given rise to many different cultures, traditions, and languages. -

Behavioral Surveillance Survey Among Refugees and Surrounding Host Community

Behavioral Surveillance Survey among Refugees and Surrounding Host Community Jhapa and Morang districts, Nepal November 2005 Acknowledgements The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) commissioned New Era to conduct the first round of a behavioral surveillance survey (BSS) in the Bhutanese refugee camps and surrounding host communities in south-eastern Nepal. UNHCR wishes to express its thanks and appreciation to every member of the New ERA survey team for successfully conducting the BSS. Special thanks go to key team members Mr. Matrika Chapagain, Mr. Niranjan Dhungel, Mr. Manik Ram Maharjan, and Ms. Jyoti Manandhar. Many organizations and individuals contributed to the successful completion of this study. UNHCR wishes to express its sincere gratitude to the concerned officials from AMDA-Nepal, Lutheran World Federation-Nepal, Damak Municipality, the Refugee Coordination Unit of the Government of Nepal, the camp secretaries and sector/sub-sector heads of the seven refugee camps, and key- informants from the host community for their contribution in providing support during the fieldwork phase of the survey. Special thanks go to Dr. Sathyanarayanan Doraiswamy and Ms. Jayshree Jayanand from UNHCR, Damak Sub-office, and Dr. Nirmal Rimal and Dr. Durga Prasad Bhandari from AMDA-Nepal, Primary Health Care Centre for Bhutanese Refugees, Jhapa for providing valuable assistance and advice throughout the whole survey. Special appreciation also goes to Dr. Paul Spiegel (UNHCR, Geneva), Dr. Ann Burton (UNHCR, Bangkok), and Mr. Kurt Burja (Columbia University, Mailman School of Public Health) for reviewing and revising the final report. Finally, UNHCR thanks the respondents from the refugee and surrounding host communities who provided their valuable time for interviews and sharing their personal experiences. -

Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal

SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics Acknowledgements The completion of both this and the earlier feasibility report follows extensive consultation with the National Planning Commission, Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), World Food Programme (WFP), UNICEF, World Bank, and New ERA, together with members of the Statistics and Evidence for Policy, Planning and Results (SEPPR) working group from the International Development Partners Group (IDPG) and made up of people from Asian Development Bank (ADB), Department for International Development (DFID), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), UNICEF and United States Agency for International Development (USAID), WFP, and the World Bank. WFP, UNICEF and the World Bank commissioned this research. The statistical analysis has been undertaken by Professor Stephen Haslett, Systemetrics Research Associates and Institute of Fundamental Sciences, Massey University, New Zealand and Associate Prof Geoffrey Jones, Dr. Maris Isidro and Alison Sefton of the Institute of Fundamental Sciences - Statistics, Massey University, New Zealand. We gratefully acknowledge the considerable assistance provided at all stages by the Central Bureau of Statistics. Special thanks to Bikash Bista, Rudra Suwal, Dilli Raj Joshi, Devendra Karanjit, Bed Dhakal, Lok Khatri and Pushpa Raj Paudel. See Appendix E for the full list of people consulted. First published: December 2014 Design and processed by: Print Communication, 4241355 ISBN: 978-9937-3000-976 Suggested citation: Haslett, S., Jones, G., Isidro, M., and Sefton, A. (2014) Small Area Estimation of Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal, Central Bureau of Statistics, National Planning Commissions Secretariat, World Food Programme, UNICEF and World Bank, Kathmandu, Nepal, December 2014. -

The Project on Rehabilitation and Recovery from Nepal Earthquake

Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) The Project on Rehabilitation and Recovery from Nepal Earthquake Inception Report (Draft) July 2015 ORIENTAL CONSULTANTS GLOBAL CO., LTD. Pacific Consultants Co., Ltd. MOHRI, ARCHITECT & ASSOCIATES, INC CTI Engineering International Co., Ltd. PASCO CORPORATION Location Map of Project Area Nepal Kathmandu Valley Kathmandu District Kathmandu Bhaktapur District Kirtipur Bhaktapu r Madhyapur Thimi Lalitpur Kathmandu Valley district line City line Lalitpur District Village line Table of contents Location Map of Study page 1. Overview of the Project ................................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Background of the Project ........................................................................................................................................ 1 1.2 Purpose and Scope of the Project ............................................................................................................................. 1 1.3 Outputs of the Project ............................................................................................................................................... 2 1.4 Project counterpart organizations ............................................................................................................................. 3 1.5 Target area of the Project ......................................................................................................................................... -

49215-001: Earthquake Emergency Assistance Project

Environmental Assessment Document Initial Environmental Examination Loan: 3260 July 2017 Earthquake Emergency Assistance Project: Panchkhal-Melamchi Road Project Main report-I Prepared by the Government of Nepal The Environmental Assessment is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Government of Nepal Ministry of Physical Infrastructure and Transport Department of Roads Project Directorate (ADB) Earthquake Emergency Assistance Project (EEAP) (ADB LOAN No. 3260-NEP) INITIAL ENVIRONMENTAL EXAMINATION OF PANCHKHAL - MELAMCHI ROAD JUNE 2017 Prepared by MMM Group Limited Canada in association with ITECO Nepal (P) Ltd, Total Management Services Nepal and Material Test Pvt Ltd. for Department of Roads, Ministry of Physical Infrastructure and Transport for the Asian Development Bank. Earthquake Emergency Assistance Project (EEAP) ABBREVIATIONS AADT Average Annual Daily Traffic AC Asphalt Concrete ADB Asian Development Bank ADT Average Daily Traffic AP Affected People BOD Biological Oxygen Demand CBOs Community Based Organization CBS Central Bureau of Statistics CFUG Community Forest User Group CITIES Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species CO Carbon Monoxide COI Corridor of Impact DBST Double Bituminous Surface Treatment DDC District Development Committee DFID Department for International Development, UK DG Diesel Generating DHM Department of Hydrology and Metrology DNPWC Department of National -

District Report Housing Recovery and Reconstruction Platform, Nepal Housing Recovery and Reconstruction Platform

Monthly District Report Housing Recovery and Reconstruction Platform, Nepal Housing Recovery and Reconstruction Platform District Report Sindhupalchok 15 March – 11 April 2019 Summary of events during this period Name of activity/event Event date Participants Contact Person Reference Document summary Male Female Ward Level Coordination Meeting, 14 Mar, 2019 5 2 Pradip Sharma Meeting Minutes of the Helambu RM-2 event Hollow Concrete Block Manual 18th and 19th 114 5 Pradip Sharma, Activity Report of the Orientation March, 2019 Pranjal Bhandari event District General Coordination 26 Mar, 2019 14 6 Pradip Sharma, Meeting minutes to the Meeting Pranjal Bhandari event Ward Level Coordination 8th April, 2019 0 8 Pranjal Bhandari, Meeting, Barhabise Municipality- Pradip Sharma 6 Palika Level Coordination 8th April, 2019 15 0 Pranjal Bhandari, Meeting Pradip Sharma Palika level Coordination meeting 10-April, 2019 11 2 Upcoming Events & Meetings Name of activity/event Date, Time, and Organizer Contact Person Location General Coordination Meeting 23-Apr-2019, 11:00 HRRP Pranjal Bhandari, Pradip Sharma AM, Chautara Tranche Status Chautara Helambu Indrawati Jugal Lisankhu Melamchi Panch Sunkoshi Tripura Rural Balefi Barhabise Bhotekoshi sangachok RM RM RM Pakhar NP pokhari RM Sundari /Municipality RM Mun RM gadhi RM Thangpal RM Mun RM Total HHs Surveyed Total HHs 8323 5665 5374 13374 7181 5739 4591 6043 7903 4225 13989 5421 Eligible Total HHs 8049 5524 4932 13056 6784 5563 4462 5964 7727 4131 13723 5176 Enrolled First Tranche 5964 7727 4131 13723 5176 -

Provincial Summary Report Province 3 GOVERNMENT of NEPAL

National Economic Census 2018 GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Economic Census 2018 Provincial Summary Report Province 3 Provincial Summary Report Provincial National Planning Commission Province 3 Province Central Bureau of Statistics Kathmandu, Nepal August 2019 GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Economic Census 2018 Provincial Summary Report Province 3 National Planning Commission Central Bureau of Statistics Kathmandu, Nepal August 2019 Published by: Central Bureau of Statistics Address: Ramshahpath, Thapathali, Kathmandu, Nepal. Phone: +977-1-4100524, 4245947 Fax: +977-1-4227720 P.O. Box No: 11031 E-mail: [email protected] ISBN: 978-9937-0-6360-9 Contents Page Map of Administrative Area in Nepal by Province and District……………….………1 Figures at a Glance......…………………………………….............................................3 Number of Establishments and Persons Engaged by Province and District....................5 Brief Outline of National Economic Census 2018 (NEC2018) of Nepal........................7 Concepts and Definitions of NEC2018...........................................................................11 Map of Administrative Area in Province 3 by District and Municipality…...................17 Table 1. Number of Establishments and Persons Engaged by Sex and Local Unit……19 Table 2. Number of Establishments by Size of Persons Engaged and Local Unit….….27 Table 3. Number of Establishments by Section of Industrial Classification and Local Unit………………………………………………………………...34 Table 4. Number of Person Engaged by Section of Industrial Classification and Local Unit………………………………………………………………...48 Table 5. Number of Establishments and Person Engaged by Whether Registered or not at any Ministries or Agencies and Local Unit……………..………..…62 Table 6. Number of establishments by Working Hours per Day and Local Unit……...69 Table 7. Number of Establishments by Year of Starting the Business and Local Unit………………………………………………………………...77 Table 8. -

Sindhupalchok District - Gon Housing Grant: Supported by Pos (As of 25 Jul 2017) HRRP

NEPAL: Sindhupalchok District - GoN Housing Grant: Supported by POs (as of 25 Jul 2017) HRRP No. of Beneficiaries/houses Supported by POs Legend Rasuwa CARITAS 1790 GaNaPa Boundary NRCS 1493 District Boundary CHINA VDC/Municipality Boundary HELVETAS/CDECF 793 No of beneficiaries supported by POs SCI/TUKI 453 301 - 1137 WVIN/ARSOW 307 101 - 300 Upto 100 LWF/GMSP 142 Approved beneficiaries for installment Worek 51 Gumba SCI/TUKI 570 Helumbu 100 Baruwa Motang HELVETAS/CDECF 38 Jugal Gaupalika I Gloche II Pachpokhari Thangpal Gaupalika SCI/TUKI III Helambu Gaupalika 104 Note: Tatopani This map highlights the number of beneficiaries/houses NRCS have been Supported by POs (INGOs) for II installment 683 in Sindhupalchok district.The figure of beneficiaries/ houses was sourced form HRRP 4W-R35 . Further, Thanpalkot Nuwakot Kiwool the labels in the map (Example: Gumba- 100) means Ichok that 100 beneficiaries/houses have been Supported for Gunsakot GoN installment by POs as the labels (name) in the HELVETAS/CDECF HELVETAS/CDECF respective VDC/ Municipality. 119 Listikot 184 Bhotekoshi Gaupalika ThampalChhap Sindhupalchok Banskharka Pangtang Map Doc Name: HousingGrant_POs_Sindhupalchok Palchok Mahankal BhoteNamlang Fulpingkatti GLIDE Number: EQ-2015-000048-NPL Dubachour Creation Date: 10 Jul 2017 HELVETAS/CDECF 130 Dhuyang Lagarche Baramchi HELVETAS/CDECF Map Data Source:HRRP 4W/MoUD/DLPIU (25 Jul 17) 104 LWF/GMSP Hagam (Ghumthang) Thakani Selang 142 Marming Geo Data Source: DoS, MoFALD; Web Resource: www.hrrpnepal.org Melamchi N.P. SipalKavre Gati Melamchi N.P. Nawalpur Barhabise Gaupalika Haibung SyauleBazar Jalbire HELVETAS/CDECF Batase Maneswor 218 Bahrabise Karthali Fulpingkot ¯ Bhotechaur Indrawati Gaupalika Badegau Kunchok Ramche Ghorthali (1 : 250,000) Chautara N.P. -

WASH Cluster Nepal 4W - May 12Th 2015

WASH Cluster Nepal 4W - May 12th 2015 Please find following the analysis of the 4W data – May 12th Introduction (Round 2) This is the second round of the 4W analysis. As this is the second round and still early in the emergency response, many agencies are still planning their interventions and caseloads, hence much of the data is understandably incomplete. In the coming week/s we will receive far more comprehensive partner data and will be able to show realistic gaps. In addition, we are receiving better affected population data and there are many ongoing assessments, the results of which will help us to understand both the response data and the affected population data and enable us to deliver a far more profound analysis of the WASH response. Please assist us as we have a lot of information gaps in the data provided so far and hence the maps are not yet providing a true picture of the response. We would like to quickly move to VDC mapping including planned/reached beneficiaries. Since the first round of reporting, agencies have provided substantially more VDC‐level data – as of today, of 740 WASH activities identified, 546 of these (74%) are matched to an identified VDC ‐ this is a big improvement from last week (which had VDC data for 192 of 445 activities, or 43%) The Highlights ・ 47 Organisations – number of organisations that reported in Round 1 and/or Round 2 of the WASH 4W ・ 206 VDCs – where WASH interventions taking place/planned (in 15 districts) 4W – WASH May 12th 2015 Water0B Spread of water activities ‐ targeted Temporary -

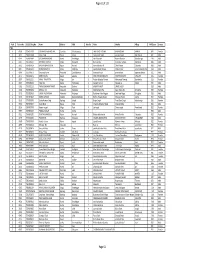

TSLC PMT Result

Page 62 of 132 Rank Token No SLC/SEE Reg No Name District Palika WardNo Father Mother Village PMTScore Gender TSLC 1 42060 7574O15075 SOBHA BOHARA BOHARA Darchula Rithachaupata 3 HARI SINGH BOHARA BIMA BOHARA AMKUR 890.1 Female 2 39231 7569013048 Sanju Singh Bajura Gotree 9 Gyanendra Singh Jansara Singh Manikanda 902.7 Male 3 40574 7559004049 LOGAJAN BHANDARI Humla ShreeNagar 1 Hari Bhandari Amani Bhandari Bhandari gau 907 Male 4 40374 6560016016 DHANRAJ TAMATA Mugu Dhainakot 8 Bali Tamata Puni kala Tamata Dalitbada 908.2 Male 5 36515 7569004014 BHUVAN BAHADUR BK Bajura Martadi 3 Karna bahadur bk Dhauli lawar Chaurata 908.5 Male 6 43877 6960005019 NANDA SINGH B K Mugu Kotdanda 9 Jaya bahadur tiruwa Muga tiruwa Luee kotdanda mugu 910.4 Male 7 40945 7535076072 Saroj raut kurmi Rautahat GarudaBairiya 7 biswanath raut pramila devi pipariya dostiya 911.3 Male 8 42712 7569023079 NISHA BUDHa Bajura Sappata 6 GAN BAHADUR BUDHA AABHARI BUDHA CHUDARI 911.4 Female 9 35970 7260012119 RAMU TAMATATA Mugu Seri 5 Padam Bahadur Tamata Manamata Tamata Bamkanda 912.6 Female 10 36673 7375025003 Akbar Od Baitadi Pancheswor 3 Ganesh ram od Kalawati od Kalauti 915.4 Male 11 40529 7335011133 PRAMOD KUMAR PANDIT Rautahat Dharhari 5 MISHRI PANDIT URMILA DEVI 915.8 Male 12 42683 7525055002 BIMALA RAI Nuwakot Madanpur 4 Man Bahadur Rai Gauri Maya Rai Ghodghad 915.9 Female 13 42758 7525055016 SABIN AALE MAGAR Nuwakot Madanpur 4 Raj Kumar Aale Magqar Devi Aale Magar Ghodghad 915.9 Male 14 42459 7217094014 SOBHA DHAKAL Dolakha GhangSukathokar 2 Bishnu Prasad Dhakal -

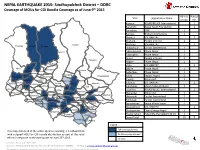

NEPAL EARTHQUAKE 2015: Sindhupalchok District – DDRC Coverage of Mous for CGI Bundle Coverage As of June 9Th 2015

NEPAL EARTHQUAKE 2015: Sindhupalchok District – DDRC Coverage of MOUs for CGI Bundle Coverage as of June 9th 2015 All HHs Partial VDC Organization Name of VDC HH Atarpur ASSAB/RELIEF International 1 Baramchi Nepal Youth Foundation 1 Barhabise IOM 1 Baruwa Global Communities 1 Bhimtar UN-HABITAT 1 Bhotang People in Need 1 Gumba Bhotsipa UN-HABITAT 1 Helambu Baruwa Bhotang Duwachaur Caritas Switzerland 1 Golche Fulpingdanda Phase Nepal 1 Fulpingkot Phase Nepal 1 Gunsa People in Need 1 Tatopani Hagam Phase Nepal 1 Thapalkot Irkhu UN-HABITAT 1 Ichok Kiul Ghunsakot Jalbire Phase Nepal 1 Ghuyang (Thanpalchap) Listokot Banskharka Kadambas Phase Nepal 1 Pangtang Palchok Mahangkal Bhotenamlang Phulpingkatti Kalika Impact Nepal 1 Kiwool Action Aid 1 Dubachaur Lagarche Baramchae Dhuyang Talamarang Kubinde UN-HABITAT 1 Thakani Jyamire Selang Hagam Marming Melamchi Sinpal Kavre Gati Kunchowk Micah Network Nepal 1 Sindhukot Syaule Jalbire Haibung ShikharpurNawalpur Batase Lisankhu ASSAB/RELIEF International 1 Bansbari Maneswar Barhabise Karthali Bhotechaur Phulpingkot Mahankal Action Aid 1 Bandegaun KunchokPipaldanda Ramche Ghorthali ChautaraKubhinde Mangkha Melamchi Caritas Switzerland 1 PhataksilaSipapokharae Gunsakun Sanusirubari Phulchodanda Tekanpur Chokati Palchowk Caritas Switzerland 1 Irkhu Pangretar BhimtarBhotsipa Piskar Sanosirubari Peace Winds Japan 1 Kadambas Thumpakhar Thulo Sirubari Pedku Yamuna Danda Tauthali Sipapokhare UN-HABITAT 1 SunkhaniThulo Pakhar Thulopakhar Clean Energy Nepal 1 Sangachok Kalika Jethal Thokarpa Attarpur Thulosirubari Help-hilfe the Selbsthilfe CV 1 Grand Total 19 8 Lisangkhu Thulo Dhading Legend Full coverage planned This map details all of the active agencies working in Sindhupalchok with a signed MOU for CGI bundle distribution as part of the relief Partial coverage planned th efforts in response to the earthquake on April 25 2015. -

BTTM-8Th-Sem-Syllabus-2018.Pdf

Tribhuvan University Faculty of Management Office of the Dean Course detail of BTTM (Bachelor of Travel and Tourism Management) 8th Semester Semester outline TTM 339 Strategic Management for Travel and Tourism 3 Cr. hrs TTM 354 Tourism Legislation 3 Cr. hrs TTM 355 Culture Heritage and Religion 3 Cr. hrs Elective Course (Any TWO) 6 Cr. hrs TTM 445 Tourism and Aviation TTM 446 Tourism for Peace and Progress TTM 447 Pilgrimage and Religious Tourism TTM 448 Airline Operations and Management TTM 450 Food and Beverage Services 4-Year Syllabus (Effective from the admission batch of 2014 AD onwards) TTM 339: Strategic Management for Travel and Tourism Credits: 3 Lecture Hours: 48 Course Objectives: The objective of this course is to impart analytical tools and approaches for strategy formulation in order to enable students to understand analyze and formulate corporate strategies and policies in tourism and hospitality. Course Description: This course focuses on the strategy formulation and implementation which includes introduction of strategy and strategic management, strategic analysis, strategic formulation for tourism, strategic alternatives for tourism and hospitality industries in global world, strategy implementation, and strategic control. Course Details Unit 1: Introduction to Strategy and Strategic Management LH10 Meaning of strategy, process of strategy, importance of strategy, elements of strategy, levels of strategy, mission, vision and mission statement, contexts and uses of strategy in tourism, competing approaches to strategy, Definition of strategic management, growing relevance of Strategic Management in Tourism. Unit 2: Strategic Analysis LH8 Meaning of internal and external environment, External environmental analysis: political, economic, socio-cultural, technological, porter's five forces analysis, destination competitiveness, determination of opportunities and threats through environment analysis, ethical issues.