Book Reviews 2000S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

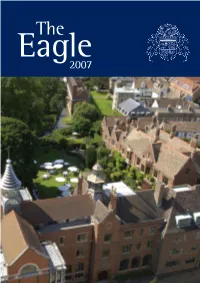

The Eagle 2007 the Eagle 2007

The Eagle 2007 The Eagle 2007 ST JOHN’S COLLEGE CAMBRIDGE The Eagle 2007 The Eagle is published annually by St John’s College, Cambridge, and sent free of charge to members of St John’s College and other interested parties. Articles to be considered for publication should be addressed to: The Editor, The Eagle, Development Office, St John’s College, Cambridge, CB2 1TP. St John’s College Cambridge CB2 1TP http://www.joh.cam.ac.uk/ General telephone enquiries: 01223 338600 General fax enquiries: 01223 337720 General email enquiries: [email protected] Printed by Cambridge University Press Published by St John’s College, Cambridge, 2007 CONTENTS Message from the Master . 5 Message from the Development Office . 11 Commemoration of Benefactors . 14 Remembering Hugh Sykes Davies . 20 After-dinner Speech by Clifford Evans . 29 A Legal Eagle . 34 Spirit of the Brits . 36 Going Down 1949 . 44 Twenty-five Years of Women at St John’s . 46 Bicentenary of the Act for the Abolition of the Slave Trade . 49 Hidden in Plain Sight: Slavery and Justice in Rhode Island . 52 St John’s Most Historical Moment? . 63 Book Reviews . 80 Obituaries . 96 College Societies . .125 Photography Competition . 164 College Sports . 172 College Notes . 211 Fellows’ Appointments and Distinctions . 219 Members’ News . 221 Donations to the Library . 283 Errata . 296 MESSAGE FROM THE MASTER There is much to take cheer from in the events of the past year, and it is my privilege to select here a few items for closer scrutiny. I also take the opportunity to make a few valedictory remarks about the College and its future. -

Writing the 9/11 Decade

1 Writing the 9/11 Decade Charlie Lee-Potter A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of PhD ROYAL HOLLOWAY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON 2013 2 Declaration of Authorship I Charlie Lee-Potter hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: ______________________ Date: ________________________ 3 Charlie Lee-Potter, Writing the 9/11 Decade Novelists have struggled to find forms of expression that would allow them to register the post-9/11 landscape. This thesis examines their tentative and sometimes faltering attempts to establish a critical distance from and create a convincing narrative and metaphorical lexicon for the historical, political and psychological realities of the terrorist attacks. I suggest that they have, at times, been distracted by the populist rhetoric of journalistic expression, by a retreat to American exceptionalism and by the demand for an immediate response. The Bush administration’s statement that the state and politicians ‘create our own reality’ served to reinforce the difficulties that novelists faced in creating their own. Against the background of public commentary post-9/11, and the politics of the subsequent ‘War on Terror’, the thesis considers the work of Richard Ford, Paul Auster, Kamila Shamsie, Nadeem Aslam, Don DeLillo, Mohsin Hamid and Amy Waldman. Using my own extended interviews with Ford, Waldman and Shamsie, the artist Eric Fischl, the journalist Kevin Marsh, and with the former Archbishop of Canterbury Dr. Rowan Williams (who is also a 9/11 survivor), I consider the aims and praxis of novelists working within a variety of traditions, from Ford’s realism and Auster’s metafiction to the post- colonial perspectives of Hamid and Aslam, and, finally, the end-of-decade reflections of Waldman. -

Iraq's News Media After Saddam

Iraq’s News Media After Saddam: Liberation, Repression, and Future Prospects A Report to the Center for International Media Assistance By Sherry Ricchiardi March 10, 2011 The Center for International Media Assistance (CIMA), a project of the National Endowment for Democracy, aims to strengthen the support, raise the visibility, and improve the effectiveness of media assistance programs by providing information, building networks, conducting research, and highlighting the indispensable role independent media play in the creation and development of sustainable democracies around the world. An im- portant aspect of CIMA’s work is to research ways to attract additional U.S. private sector interest in and support for international media development. CIMA convenes working groups, discussions, and panels on a variety of topics in the field of media development and assistance. The center also issues reports and recommendations based on working group discussions and other investigations. These reports aim to provide policymakers, as well as donors and practitioners, with ideas for bolstering the effectiveness of media assistance. Marguerite H. Sullivan Senior Director Center for International Media Assistance National Endowment for Democracy 1025 F Street, N.W., 8th Floor Washington, D.C. 20004 Phone: (202) 378-9700 Fax: (202) 378-9407 Email: [email protected] URL: http://cima.ned.org About the Author Sherry Ricchiardi Sherry Ricchiardi, Ph.D., is a contributing writer for American Journalism Review (AJR), specializing in international issues, and a professor at the Indiana University School of Journalism. Since 2001, she has reported for AJR on media coverage of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, interviewing dozens of correspondents on the ground there. -

Podcasting for Community Organisations

Podcasting for Community Organisations An introduction to podcast and community radio production for charities and community organisations Podcasting for Community Organisations by Davy Sims 3 手 Firsthand Guides First published September 2016 by David Sims Media as “Podcasting for Communities” davidsimsmedia.com Firsthand Guide to Podcasting for Community Organisations July 2017 Firsthand Guides Cultra Terrace Holywood BT18 0BA Firsthandguides.com Copyright © 2017 by Firsthand Guides, Ltd. ISBN: 9781521531112 The right of Davy Sims to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 All rights reserved For more information about Firsthand Guide books visit www.firsthandguides.com 5 Dedication To my wife, Dawn and sons Adam and Owen To hear podcasts mentioned in this book visit http://www.davysims.com/category/podcastingfor-project/ or short link http://bit.ly/DS-podcasting 7 Contents Introduction ......................................................................................................... 15 Part 1 - The production plan ................................................................................ 18 Chapter 1: Purpose .......................................................................................... 20 Here are some purposes ................................................................................ 25 “To get the word out”.................................................................................. 25 Developing professional -

Voices in Real Time Interactive and Transmedia Testimonies of the Arab Spring, Instant Archive and New Social Movements Discourses

International PHD Programme in Audiovisual Studies University of Udine, DAMS Gorizia a.a.20 !"20 # Voices in real time Interactive and transmedia testimonies of the Arab Spring, instant archive and new social movements discourses $andidate% &udovica Fales Su)ervisors% *oy Menarini, University of Bologna Ian C,ristie, Bir-.e'- College London 1 /The wor- of our time is to clarify to itself t,e meaning of its o1n desires' 2. Mar3, 'For a Rut,less Criticism of Everyt,ing E3isting' (16!!7 1 2. Mar3, /(or a *ut,less $riticism of 4veryt,ing 43isting,/ in Te Marx- ngles !eader, ed *obert $. 8u'-er, 2nd edition, Ne1 Yor-, W.;. Norton, p. <=6, 12> # 2 I9D4? Introduction "e#ning the research field : transmedia or interactive documentaries% &owards a de#nition of interactive documentaries as '(living( entities )h* is this useful in relation to Tahrir S+uare? xploring the research field. What actions and whose voices% Than-s $,a)ter I – "ocumenting events in the ma-ing toda* 1.1. Documenting collective events in their actuality. A Pre-,istory .,.,., Te formation of the modern public sphere$ actualit* and participation -Te philosophical concept of actualit* - nlightenment as re/ective consciousness on the present -0lashes and fragments of the present time -Actualit* as gathering the present .,.,2 "Te whole world is watching3, Witnessing and showing d*namic in narrating dissent -A new consciousness of news media in the Chicago.567 revolt -"ocumenting and producing media protests (.59:-2::.; - September 1., 2::.. “Te death of detachment( in the news 1.2 Glo.al imagination, actuality, present>tense, real>time .,2,., =lobal imagination, >ocal imagining, A 4ultural Studies &oolbox for Media !epresentation in the =lobal World -=lobal Imagination, Local Imagining -?e*ond '@rientalism'% - Self-narratives, testimonies, micro narratives .,2,2, Te Space of Tahrir S+uare- Within and Without -A Space-in-process -A Space Extended to Tose Watching It -Aerformativit* of Tahrir S+uare - Social Media, Social Change and CitiBen Witnessing – A Faceboo- revolution% .,2,D, Can Tahrir S+uare 2:. -

The Military's Role in Counterterrorism

The Military’s Role in Counterterrorism: Examples and Implications for Liberal Democracies Geraint Hug etortThe LPapers The Military’s Role in Counterterrorism: Examples and Implications for Liberal Democracies Geraint Hughes Visit our website for other free publication downloads http://www.StrategicStudiesInstitute.army.mil/ To rate this publication click here. hes Strategic Studies Institute U.S. Army War College, Carlisle, PA The Letort Papers In the early 18th century, James Letort, an explorer and fur trader, was instrumental in opening up the Cumberland Valley to settlement. By 1752, there was a garrison on Letort Creek at what is today Carlisle Barracks, Pennsylvania. In those days, Carlisle Barracks lay at the western edge of the American colonies. It was a bastion for the protection of settlers and a departure point for further exploration. Today, as was the case over two centuries ago, Carlisle Barracks, as the home of the U.S. Army War College, is a place of transition and transformation. In the same spirit of bold curiosity that compelled the men and women who, like Letort, settled the American West, the Strategic Studies Institute (SSI) presents The Letort Papers. This series allows SSI to publish papers, retrospectives, speeches, or essays of interest to the defense academic community which may not correspond with our mainstream policy-oriented publications. If you think you may have a subject amenable to publication in our Letort Paper series, or if you wish to comment on a particular paper, please contact Dr. Antulio J. Echevarria II, Director of Research, U.S. Army War College, Strategic Studies Institute, 632 Wright Ave, Carlisle, PA 17013-5046. -

BBC Annual Report 2020/11 Part

PART 2 THE BBC EXECUTIVE’S REVIEW AND ASSESSMENT Overview Delivering our strategy Managing the business Governance Managing our finances Part 2 BBC Executive Overview Managing the business 2-1 Director-General’s introduction 2-38 Chief Operating Officer’s review 2-2 Understanding the BBC’s finances 2-39 Increasing value 2-4 Performance by service 2-50 Looking forward 2-8 Television Governance 2-9 Radio 2-52 Executive Board 2-10 News 2-54 Risks and opportunities 2-11 Future Media 2-56 Governance report 2-12 Nations and Regions Managing our finances Delivering our strategy 2-68 Chief Financial Officer’s review 2-14 Meeting the BBC’s Purposes 2-69 Summary financial performance 2-16 The best journalism in the world 2-70 Financial overview 2-20 Inspiring knowledge, culture and music 2-79 Looking forward 2-24 Ambitious UK drama and comedy 2-80 Beyond broadcasting 2-28 Outstanding children’s content 2-82 Glossary 2-32 Bringing the nation together 2-83 Contact us/More information 2-36 Delivering Quality First objectives Subject index Part 1 Part 2 Appreciation index by service 2-4 to 2-7 Audience approval – KPI 1-6 2-23 Board remuneration from 2011/12 2-61 Board remuneration 2010/11 1-20 2-60 Commercial companies 1-19 2-46/2-69 Content spend by service 1-19 2-4 to 2-7 Delivering Quality First 1-7 2-36 Digital switchover 1-9 2-40 Distinctiveness – KPI 1-6/1-25 2-31 Efficiencies 1-7 2-69/2-71 Innovation 2-45 Licence fee 1-24 2-3 Licence fee spend 1-17 2-69/2-73 News audiences 1-8/1-13 2-19 Public purposes 1-8 2-14 Quality – KPI 1-6 2-27 Radio from -

British Cult Comedy.Indb 215 16/8/06 12:34:16 Pm Cult Comedy Club up the Creek in Greenwich, Southeast London

Geography Lessons: comedy around Britain British Cult Comedy.indb 215 16/8/06 12:34:16 pm Cult comedy club Up The Creek in Greenwich, southeast London British Cult Comedy.indb 216 16/8/06 12:34:17 pm Geography Lessons: comedy around Britain Comedy just wouldn’t be comedy without local roots. And that is why, in this chapter, we take you on a tour of British comedy from Cornwall to the Scottish Highlands, visiting local comedic landmarks, clubs and festivals. Comedy is prey to the same homogenizing forces Do Part, was successfully re-created in America, that have made Starbucks globally ubiquitous but Germany and Israel, suggesting that comedy that humour doesn’t travel so easily or predictably as touches, however lightly, on universal truths can cappuccino. In the past, slang, regional vocabu- be exported around the world. lary, accents and local knowledge have often A comic’s roots, cherished or spurned, are limited a comic’s appeal, explaining why such crucial to their humour. The small screen has acts as George Formby and Tommy Trinder never made it easier for contemporary acts – nota- quite transcended the north/south divide. Yet a bly Johnny Vegas, Peter Kay and Ben Elton character as localized as Alf Garnett, the charis- – to achieve national recognition while retain- matic Cockney bigot in the sitcom Till Death Us ing a regional identity. Since the 1980s, a more 217 British Cult Comedy.indb 217 16/8/06 12:34:17 pm GEOGRapHY LESSONS: COmedY arOUND brItaIN adventurous approach to sitcoms has meant that theme to British comedy, it was that, as Linda shows such as The Royle Family have had a much Smith told him: “A lot of comics come from more authentic local flavour than most of their the edge of nowhere.” Smith often argued with predecessors. -

The Eagle 2016 Eagle The

The Eagle 2016 The Eagle 2016 THE EAGLE 2016 Volume 98 THE EAGLE Published in the United Kingdom in 2016 by St John’s College, Cambridge St John’s College Cambridge CB2 1TP johnian.joh.cam.ac.uk Telephone: 01223 338700 Fax: 01223 338727 Email: [email protected] Registered charity number 1137428 First published in the United Kingdom in 1858 by St John’s College, Cambridge Designed by Cameron Design (01284 725292, www.designcam.co.uk) CONTENTS & Printed by Lonsdale Direct (01933 228855, www.lonsdaledirect.co.uk) Front cover: Art and Photography Competition 2016: ‘Survivors’ taken at the May Ball 2015 by MESSAGES Bernadette Schramm (2012). Bernadette’s image was the winner of the ‘College life’ category. Previous page: Art and Photography Competition 2016: ‘Dewy footprints’ by Katherine Smith (2013) Facing page: New Court by Paul Everest The Eagle is published annually by St John’s College, Cambridge, and is sent free of charge to members of the College and other interested parties. 2 | THE EAGLE 2016 THE EAGLE 2016 | 3 CONTENTS & MESSAGES CONTENTS & MESSAGES CONTENTS College life Editorial. 7 Kathryn Wingrove – Par for the course . 132 Message from the Master . 8 JCR . 136 SBR . 139 Articles Johnian Society. 141 Holly Mason – A need for speed . 14 The Choir. 143 Frank Salmon – The horns of a dilemma. 19 St John’s Voices . 149 Mary Dobson – Sir Robert Talbor: an intriguing life and a ‘secret cure’ for malaria . 24 Student society reports. 151 Alan Gibson – Why don’t young doctors want to be psychiatrists? . 30 Student sports team reports . -

London Book Fair Guide 2021

London Book Fair Guide 2021 Jonathan Clowes Literary Agents 10 Iron Bridge House Bridge Approach London NW1 8BD, UK telephone: +44 (0) 20 7722 7674 www.jonathanclowes.co.uk Ann Evans [email protected] Nemonie Craven [email protected] Cara Lee Simpson [email protected] Tufayel Ahmed The Estates of Michael Baigent & Richard Leigh Dr. David Bellamy OBE Frances Bingham Jacqueline Bublitz Angela Chadwick Bethany Clift Arthur Conan Doyle Characters Ltd. Simon Critchley Maureen Duffy Brian Freemantle Miles Gibson Rana Haddad Ben Halls Francesca Hornak The Estate of Elizabeth Jane Howard CBE The Estate of Carla Lane The Estate of Doris Lessing CH The New York Times The Estate of David Nobbs Okechukwu Nzelu Gruff Rhys Barbara Voors The Estate of Gillian White Writing Revolution Toby Vieira Tufayel Ahmed To Hell With It Tufayel Ahmed is a journalist and editor who has previously worked as Senior Editor at Newsweek and News Editor at PinkNews. He has written for CNN, Forbes, Radio Times, VICE and more. He lives with his partner and pet Maltese, Gigi, in London. Tufayel is also a BA (Hons) Journalism lecturer at London South Bank University, and is currently leading the campaign #DiversifyTheNewsroom. In a similar vein to Queenie by Candice Carty-Williams, TO HELL WITH IT is a bold and witty upmarket commercial fiction novel exploring love, race, sexuality, mental health, and the ties of family and friendship in con- temporary multicultural Britain. It follows its unforgettable protagonist Am- ar, a young gay, British South Asian man, after he comes out to his family. -

EXPERIMENT: a Manifesto of Young England, 1928-1931 Two Volumes

EXPERIMENT: A Manifesto of Young England, 1928-1931 Two Volumes Vol. 1 of 2 Kirstin L. Donaldson PhD University of York History of Art September 2014 Abstract This thesis examines the little magazine Experiment, published in Cambridge between 1928 and 1931. It represents the first book-length study of Experiment; and therefore offers a deeper level of engagement with the magazine’s social and historical context, its influences, and crucially, its contents. The appearance of Experiment coincided with the tenth anniversary celebrations of Armistice Day; an event which I argue was a catalyst for the formation of a new generation of artists and writers. The First World War created a rupture in society: the myth of the “lost generation” weighed heavily on those who were left behind. The Experiment group had lived through the War; however, their childhood experiences were far-removed from those of frontline soldiers. The Experimenters’ self-identification with the term “postwar” recognised the importance of the War to their sense of identity while simultaneously acknowledging their temporal separation from that moment. This thesis demonstrates how the Experiment group’s conception of themselves as a generation was constructed around their relationship to the First World War. It will be shown that they embraced their temporal distinctiveness while nonetheless attempting to situate themselves within established historical narratives. This is evidenced in the group’s appropriation and subversion of traditional avant-garde methods, for example the -

Iraq's News Media After Saddam

Iraq’s News Media After Saddam: Liberation, Repression, and Future Prospects A Report to the Center for International Media Assistance By Sherry Ricchiardi March 10, 2011 The Center for International Media Assistance (CIMA), a project of the National Endowment for Democracy, aims to strengthen the support, raise the visibility, and improve the effectiveness of media assistance programs by providing information, building networks, conducting research, and highlighting the indispensable role independent media play in the creation and development of sustainable democracies around the world. An im- portant aspect of CIMA’s work is to research ways to attract additional U.S. private sector interest in and support for international media development. CIMA convenes working groups, discussions, and panels on a variety of topics in the field of media development and assistance. The center also issues reports and recommendations based on working group discussions and other investigations. These reports aim to provide policymakers, as well as donors and practitioners, with ideas for bolstering the effectiveness of media assistance. Marguerite H. Sullivan Senior Director Center for International Media Assistance National Endowment for Democracy 1025 F Street, N.W., 8th Floor Washington, D.C. 20004 Phone: (202) 378-9700 Fax: (202) 378-9407 Email: [email protected] URL: http://cima.ned.org About the Author Sherry Ricchiardi Sherry Ricchiardi, Ph.D., is a contributing writer for American Journalism Review (AJR), specializing in international issues, and a professor at the Indiana University School of Journalism. Since 2001, she has reported for AJR on media coverage of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, interviewing dozens of correspondents on the ground there.