An Interview with Bishop Donald Bolen, Chairman of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bishop Dennis Commissioned by the Pope and the Archbishop of Canterbury and “Sent Out” for Mission

NORTHERN WITNESS What are those New Bible study humans doing? Page 7 Page 3 Advent events Page 5 NOVEMBER 2016 A SECTION OF THE ANGLICAN JOURNAL ᑯᐸᒄ ᑲᑭᔭᓴᐤ ᐊᔭᒥᐊᐅᓂᒡ • ANGLICAN DIOCESE OF QUEBEC • DIOCÈSE ANGLICAN DE QUÉBEC Bishop Dennis commissioned by the Pope and the Archbishop of Canterbury and “sent out” for mission By Gavin DrakeACNS The commissioning Drainville and Roman Catholic and sending out came in the Archbishop of Regina, Donald The Archbishop of setting of a Vespers service, Bolen. Bishop Bolen has been Canterbury Justin Welby and led jointly by Pope Francis Pope Francis have commis- and Archbishop Welby, at the sioned 19 pairs of Anglican Church of Saint Gregory on and Roman Catholic bishops the Caelian Hill in Rome. from across the world to take The service was one part in united mission in their of the highlights of an ecu- local areas. The bishops, se- menical summit organised lected by the International by Iarccum to mark the 50th Anglican Roman Catholic anniversary of the meeting Commission for Unity and between Pope Paul VI and Mission (Iarccum) were “sent Archbishop Michael Ramsey out” for mission together by in 1966 – the first such public the Pope and Archbishop from Archbishop Justin Welby and Pope Francis commis- meeting between a Pope and the same church were Pope sion and send out 19-pairs of bishops for joint an Archbishop of Canterbury Gregory sent Saint Augustine mission Photo Credit: Vatican Television since the Reformation. The to evangelise the English in God,” Pope Francis told the you’. We too, send you out summit, which began at the Archbishop of Regina, the sixth Century. -

Laudato Si’ , That Wealthi - Ecological Crisis,” and While Ecol - August 26

Single Issue: $1.00 Publication Mail Agreement No. 40030139 CATHOLIC JOURNAL Vol. 93 No. 6 June 24, 2015 Summer schedule God’s creation is ‘crying out with pain’ The Prairie Messenger pub - lishes every By Cindy Wooden Situating mate right” to private property, second week ecology but that right is never “absolute or in July and VATICAN CITY (CNS) — The firmly with - inviolable,” since the goods of the takes a three- earth, which was created to sup - in Catholic earth were created to benefit all. week sum - port life and give praise to God, is social teach - Regarding pollution and envi - crying out with pain because ing, Pope ronmental destruction in general, mer vacation in August. human activity is destroying it, Francis not he says it is important to acknowl - Summer issues will be dated Pope Francis says in his long- only insists edge “the human origins of the July 1, July 15, July 29 and awaited encyclical, Laudato Si’ , that wealthi - ecological crisis,” and while ecol - August 26. on Care for Our Common Home.” er nations ogy is not only a religious con - All who believe in God and all — who con - cern, those who believe in God Bred in the bone people of goodwill have an obli - tributed should be especially passionate on gation to take steps to mitigate cli - more to the subject because they profess Grace must be bred in the mate change, clean the land and despoiling the divine origin of all creation. bone, says the seas, and start treating all of the earth — Pope Francis singles out for spe - Gordon creation — including poor people must bear cial praise Orthodox Ecumenical Smith, pres - — with respect and concern, he more of the Patriarch Bartholomew of Constan - ident of says in the document released at costs of ti nople, who has made environ - Ambrose the Vatican June 18. -

May 2019 SASKATCHEWAN KNIGHTLINE

Page 1 Volume 9 Issue 7 May 2019 SASKATCHEWAN KNIGHTLINE Knights of Columbus – Chevaliers de Colomb SASKATCHEWAN STATE COUNCIL – CONSEIL d’ETAT P.O. Box 61 Stn. Main Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan S6H 4N7 Editor Telephone: 306-631-1610 Peter Folk E-mail: [email protected] Web Page: www.kofcsask.com Inside this issue: State Deputy: Chris Bencharski State Chaplain: Bishop Bryan Bayda State Deputy 1 Immediate Past State Deputy: Brian Schatz Honorary State Chaplain: Archbishop Donald State Chaplain 2 State Secretary: Joe Riffel Bolen State Treasurer: Larry Packet Associate State Chaplain: Fr. Ed Gibney State Office 3 State Advocate: Rene Gaudet State Executive Secretary: Gerry Gieni Cultural Diversity 4 State Warden: Marte Clemete Nogot Press Release 6 STATE DEPUTY’S MESSAGE Insurance 7 State Activities 8 Dear Brother Knights of Saskatchewan, In Memorium 15 Degrees 16 As of today, there are exactly 6 weeks left in the Columbian year. As we look back on the accomplishments of the past year, we can be proud that Saskatchewan had a great Council Activities 17 Columbian year in programming and membership. Special thanks to each individual for your Webmaster 27 assistance and support to reach many of our accomplishments - we could not have done any Editor 27 of this without a team effort. KofC Sask Charitable Two major programs, the Vocations Endowment which reached close to $560,000.00 in 28 Foundation donations in one year and the Conscience Protection Campaign which gathered more than 14,000 letters were both very successful. Thanks to all the councils for your support and involvement. Specials thanks to the bishops and priests for allowing us to conduct these two campaigns as well as many other programs in our churches throughout Saskatchewan. -

Ecumenical Spirit Sandra Beardsall…………...…...………………………………

Touchstone Volume 32 June 2014 Number 2 THE BLESSING AND CHALLENGE OF ECUMENISM CONTENTS Editorial …………....………………..……….……….…………...…… 3 Articles Receptive Ecumenism: Open Possibilities for Christian Renewal Bishop Donald Bolen ………......................................................... 9 The Case of the Missing Ecumenical Spirit Sandra Beardsall…………...…...……………………………….. 18 “We intend to move together”: the Tenth Assembly of the World Council of Churches Bruce Myers ................................................................................. 28 Christian Identity and Ecumenical Dialogue Andrew O’Neill ………………...……………………………….. 37 The Kind of Unity the New Testament Reveals David MacLachlan ……...…...……………..…………..…………46 From the Heart about the Heart of the Matter Karen A. Hamilton …………………………………...………… 52 Profile Gordon Domm, Urban Ministry Visionary Betsy Anderson ……..……...…………….………...….……….. 56 2 Touchstone J u n e 2 0 1 4 Reviews The Church: Towards a Common Vision World Council of Churches, Faith & Order Paper No. 214, 2013 Sandra Beardsall ........................................................................... 64 Interreligious Reading after Vatican II: Scriptural Reasoning, Comparative Theology and Receptive Ecumenism Edited by David F. Ford and Frances Clemson Julien Hammond …………………..……..........…………....….. 66 Story and Song: A Postcolonial Interplay between Christian Education and Worship by HyeRan Kim-Cragg Susan P. Howard …………………………..……….…………… 68 With Love, Lydia: The Story of Canada’s First Woman Ordained Minister by Patricia -

Archdiocese of Regina Bulletin February

February 14, 2021 6TH SUNDAY IN ORDINARY TIME HOLY ROSARY CATHEDRAL Cathedral Church of the ARCHDIOCESE OF REGINA 3125-13th Avenue, Regina, Saskatchewan, S4T 1P2 Holy Rosary Cathedral respectfully acknowledges that we are situated on Treaty 4 territory, traditional lands of First Nations and Métis people. Archbishop of Regina Archdiocese of Regina Coat of Arms MISSION STATEMENT Coat of Arms We, the Catholic Community of Holy Rosary Cathedral Parish, under the Patronage of Our Lady, are called to be a caring, outreaching church, proclaiming and celebrating our faith with all who seek a relationship with Christ. Most Rev. Donald Bolen Archbishop of Regina Rev. Danilo Rafael Administrator/Rector Very Rev. Thomas Nguyen, J.V. Sacramental Ministry Rev. Mr. Barry Wood Rev. Mr. Eric Gurash Assisting Deacons MASS TIMES PARISH OFFICE HOURS PARISH OFFICE Sunday 9 AM, 11 AM, 7 PM Mon-Thur 9AM – 4PM & Friday 9 AM – 1PM 2104 Garnet Street Tuesday-Friday 9 AM Closed: Saturdays, Sundays and Holidays Regina, SK S4T 6Y5 Saturday 9 AM, 6 PM Email: [email protected] Tel: 306-565-0909 CONFESSIONS Website: www.holyrosaryregina.ca Fax: 306-522-6526 Saturday 8 AM or by appointment FB: www.facebook.com/HolyRosaryReginaSK Hall: 306-525-5595 PASTORAL COUNCIL MEMBERS Chairperson ..................... Samira McCarthy Past Chairperson ............. Rob Chapple Pastoral Team .................. Rev. Danilo Rafael, Deacon Barry Wood & Deacon Eric Gurash Representatives: CWL …………………….....Shannon Chapple Ecumenism ........................ Gillian Brodie Finance Council ................. Jim Hall, Paul Malone Knights of Columbus ......... G.K. Tyler Wolfe Liturgy ................................ Brad Hanowski St. Vincent de Paul.............Carol Schimnosky Spiritual Life........................Krista LaBelle Leaders: Parish Adjuncts Catering ............................. Shannon Chapple Challenge Girls* ............... -

2011-02 Mini

A newsletter from the Diocese of Saskatoon February/March www.saskatoonrcdiocese.com 2011 Exploring Our Contact us at: Diocese of Saskatoon Faith Together Catholic Pastoral Centre 100 - 5th Avenue N. Saskatoon, SK. S7K 2N7 Phone: 306-242-1500 Toll Free: 1-877-661-5005 What’s inside: MESSAGE from BISHOP BOLEN • Page 2 CONGRESS DAY held in centres across diocese. • Page 3 YOUTH MINISTRY • Page 4-5 SOLAR STAINED GLASS: feature of new cathedral. • Page 7 NEW CATHOLIC CHAPLAIN for two Saskatoon hospitals. • Page 12 MINISTRY DEVELOPMENT COORDINATOR • Page 13 NEW LIBRARIAN St. John Bosco Parish support for Good Food Junction for diocesan The parish community of St. John Bosco decided to donate this year’s Christmas collection to the Resource Library. campaign to build and equip the Good Food Cooperative Grocery Store at Station 20 West, which • Page 13 will provide residents in the core neighbourhoods of the city with a source of nutritious, affordable food. St. John Bosco’s $10,887.25 donation was one of many responses to an Advent fund-raising campaign launched by Christian churches in Saskatoon for the Good Food Junction project. St. KNIGHTS of John Bosco parish representatives recently gathered to present the donation to Station 20 West COLUMBUS project coordinator Christine Smilie ( adults, left to right) : Blair Weimer, Kay Vaughn, Christine council celebrates Smilie, Walter Katelnikoff, Janine Katelnikoff, Wylma Orosz, George Blanchette, Georgiana 100th anniversary. Chartier, Shirley Blanchette, Don Cote, and Parish Life Director Theresa Winterhalt; and children • Page 16 (at front ): Hope and Dominic Thebeau. CWL anniversary in Englefeld. • Page 16 Ministry workshops Foundations adult education programs Calendar of events ................. -

St.Andrew's College

St. Andrew’s College Volume 23, Number 2, Spring 2014 ContaContaContaccct tt Convocation Celebration St. Andrew’s College conferred various Emmanuel & St. Chad) including the first ship within Saskatchewan Conference, degrees at the thirteenth joint convocation two Doctor of Ministry degrees. both on its executive and as its President; of the Saskatoon Theological Union on St. Andrew’s College awarded the Master of and in leadership at the General Council Friday, May 9th. The service was held at Divinity Degree to Kathleen Anderson, both as a Commissioner to two General Knox United Church in Saskatoon. Taylor Croissant and Bernadette Levesque. Council gatherings and in accepting a During the celebration 16 students Moses Kanhai was the recipient of an nomination for Moderator in 2012. received earned degrees from the three col - Honorary Doctor of Divinity Degree. The convocation address was given by leges (St. Andrew’s College, the Lutheran Moses was recognized for his leadership Most Reverend Donald Bolen, Bishop of Theological Seminary and The College of within his own congregations; in leader - the Roman Catholic Diocese of Saskatoon. Our Second Century Begins... In This Issue Alum News . 5 Friends We Shall Miss . 5 St. Andrew’s People . 12 Winter Refresher 2014 . 6 Gala Dinners . 13 St. Andrew’s College Going International . 7 From a Faculty Bookshelf . 14 A Resilient College . 2 St. Andrew’s College Donors . 8-9 From the Library . 15 Board Chair . 3 St. Andrew’s Second Century Fund . 10 New Library Director . 15 St. Andrew’s Welcomes The Designated St. Andrew’s College Alumni/ae . 11 Mark Your Calendars . -

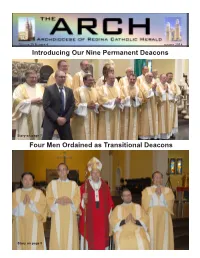

Introducing Our Nine Permanent Deacons Four Men Ordained As

VOLUME 20 NUMBER 4 SUMMER 2018 Introducing Our Nine Permanent Deacons Story on page 7 Four Men Ordained as Transitional Deacons Story on page 9 PAGE 2 - THE ARCH, SUMMER 2018 Fr. C. Lambertus Memoriam Fr. Eugene Lukasik Memoriam LAMBERTUS – Father Cyril Lambertus finished LUKASIK, Father his priestly work for the Lord Eugene Aged 86 on Friday, April 27th, 2018 at years of Moose Jaw, Whiterock, B.C. at the age of SK passed away 100 after serving as a priest peacefully on Monday, for almost 71 years. Father May 21, 2018. Father Lambertus was born May Eugene was born 30th, 1917 at the Glen Holly November 9, 1931 in farm family home four miles Czestochowa, Poland. east of Moose Jaw. He was ordained to the priesthood in Warsaw Father Lambertus completed in 1958. He left Poland his elementary studies at St. for America in 1968 Agnes School, Moose Jaw and lived in Houston, and his high school at St. Texas for a few years. Joseph’s College, Yorkton; and then studied at Campion College, Regina and St. Father Eugene came to the Regina Archdiocese in 1972 and Mary’s College, Brockville, Ontario.In September of 1943 was a Parish Priest in various places before coming to Moose he entered the Regina Diocesan Seminary for a four year Jaw in 1984. He served in Providence Hospital, Moose Jaw study of Theology. Union Hospital, St Anthony's Home, and Providence Place Father Lambertus was ordained a priest by Archbishop before retiring in 2005. Gerald Murray on June 8, 1947 at his parental parish church He is survived by his sister, Mary Smith of Tucson, Arizona. -

A Message from Archbishop Donald Bolen

VOLUME 21 NUMBER 2 WINTER 2019 A MESSAGE FROM ARCHBISHOP DONALD BOLEN Dear brothers and sisters in Christ, become one of us, for the creative Word in whom all things Grace and peace to you as you celebrate our Lord’s birth. were created to become part of that creation in, in order to redeem it - this is the incomprehensible mystery that we With Christians throughout the world, we gather with profound ponder today. What more could God do, what could be joy to ponder what God has done for us in the coming of more loving, more extravagantly generous, more lavish in Jesus. mercy, than that? Christians have always understood the birth of Jesus in The Easter season provides the full answer to that relation to God’s initial work of creation. Today pondering question. For now, we are invited to come quietly, in awe creation is an immersion into mystery, as science has come and reverence, imaginatively placing ourselves before the to an understanding that the universe came into being Eternal Word, author of all that is. Not only has God taken over 14 billion years ago, and our earth was created in the flesh, but has come in powerlessness, in vulnerability, neighbourhood of 5 billion years ago. That vastness, both in loving us into life, granting us hope, teaching us what it is terms of time and space, leaves us scratching our heads in to be human. wonder. As St. Paul wrote, “O the depth of the riches and wisdom and Equally beyond our imagining is how God, Master of the knowledge of God! How unsearchable are his judgments Universe, should become a part of that creation. -

Pope Francis and Church Accused of Covering up Abuses of Former U.S. Cardinal

Pope Francis and Church accused of covering up abuses of former U.S. cardinal A former apostolic nuncio to the United States accused church officials, including Pope Francis, of failing to act on accusations of abuse of conscience and power by now-Archbishop Theodore E. McCarrick. In an open letter first published by Lifesite News and National Catholic Register Aug. 26, Archbishop Carlo Maria Vigano, who served as nuncio to the United States from 2011-2016, wrote that he was compelled to write his knowledge of Archbishop McCarrick’s misdeeds because “corruption has reached the very top of the church’s hierarchy.” Archbishop Vigano confirmed to the Washington Post Aug. 26 that he wrote the letter and said he would not comment further. Despite repeated requests from journalists, the Vatican had not responded to the allegations by midday Aug. 26. Throughout the 11-page testimony, which was translated by a Lifesite News correspondent, the former nuncio made several claims and accusations against prominent church officials, alleging they belong to “a homosexual current” that subverted church teaching on homosexuality. Citing the rights of the faithful to “know who knew and who covered up (Archbishop McCarrick’s) grave misdeeds,” Archbishop Vigano named nearly a dozen former and current Vatican officials who he claimed were aware of the accusations. Archbishop Vigano criticized Pope Francis for not taking action against Cardinal McCarrick after he claimed he told the pope of the allegations in 2013. However, he did not make any criticism of St. John Paul II, who appointed Archbishop McCarrick to lead the Archdiocese of Washington and made him a cardinal in 2001. -

Holy Trinity Parish, Regina

July 17, 2016 Holy Trinity 16th Sunday Roman Catholic Parish in Ordinary Time 5020 Sherwood Drive New Archbishop appointed Regina, SK, S4R 4C2 for Regina, July 8, 2016 (CCCB – Ottawa)... His Holiness Pope Francis today named Phone: 306-543-3838 the Most Reverend Donald Bolen Archbishop of Regina. At Fax: 306-949-2544 the time of his appointment, he was Bishop of Saskatoon. He succeeds the Most Reverend Daniel J. Bohan who died in office January 15, 2016, at the age of 74. Since then, the Email: [email protected] Reverend Lorne Dale Crozon, the former Vicar General, has been Diocesan Administrator of the Archdiocese of Regina. Website: holytrinityregina.ca Archbishop-elect Bolen was born in Gravelbourg, Saskatchewan, on February 7, 1961. He holds an Honours B.A. in religious studies from the University of Regina, together with bache- lor's and master's degrees in theology as well as a licentiate from Saint Paul University, Ot- tawa. After being ordained priest on October 12, 1991, for the Archdiocese of Regina, he did Sunday Mass Time 10 am. post-graduate studies in theology at the University of Oxford, in addition to serving as priest for summer Return to 3 moderator in several parishes in the Archdiocese and teaching at Campion College, Univer- Masses Sept. 4.. Liturgical sity of Regina. From 2001 to 2008, he worked with the Pontifical Council for Promoting Chris- tian Unity where he served on its staff for relations with the Anglican Communion and with the ministries listing on page 3. World Methodist Council. Upon returning in 2009 to the Archdiocese of Regina, he held the Nash Chair in Religion at Campion College and served as Vicar General and pastor of several parishes before being named Bishop of Saskatoon on December 21 that year. -

Hundreds of Bodies Found at Former Saskatchewan Residential School

Hundreds of bodies found at former Saskatchewan residential school TORONTO (CNS) — The Cowessess First Nation will put a name to each of the hundreds of bodies found at the unmarked graves on the former Marieval Indian Residential School, vows Chief Cadmus Delorme. “We will put a headstone and a grave to each of them,” Delorme said at a June 24 news conference to announce the discovery of hundreds of bodies on the southeast Saskatchewan First Nations’ lands. The chief announced the discovery of up to 751 unmarked graves at the site of the Catholic residential school on its territory, the news coming almost a month after the discovery of 215 children’s bodies buried at another residential school in Kamloops, British Columbia. The graves at Marieval — which Delorme said were not part of a mass grave — were discovered by ground-penetrating radar which the First Nation, with the help of Saskatchewan Polytechnic, had been using since earlier this month on the grounds of the cemetery. He also said it’s not yet certain if all the bodies are children from the school. Delorme also stressed there could be a 10% margin of error, so he was working on the assumption there are “over 600” bodies buried at the site. “We always knew there were graves here” through oral history passed along from elders in the community, he said. The Marieval school, located about 85 miles east of Regina, Saskatchewan, opened in 1898. It was run by Catholic missionaries and funded by the federal government until 1968, when the government took over full control before handing over responsibility for the school to the Cowessess First Nation in 1987.