IASCER Resolutions Arising from the 2008 Meeting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ecclesiology of the Anglican Communion: Rediscovering the Radical and Transnational Nature of the Anglican Communion

A (New) Ecclesiology of the Anglican Communion: Rediscovering the Radical and Transnational Nature of the Anglican Communion Guillermo René Cavieses Araya Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds Faculty of Arts School of Philosophy, Religion and History of Science February 2019 1 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from this thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. © 2019 The University of Leeds and Guillermo René Cavieses Araya The right of Guillermo René Cavieses Araya to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by Guillermo René Cavieses Araya in accordance with the Copyright, Design and Patents Act 1988. 2 Acknowledgements No man is an island, and neither is his work. This thesis would not have been possible without the contribution of a lot of people, going a long way back. So, let’s start at the beginning. Mum, thank you for teaching me that it was OK for me to dream of working for a circus when I was little, so long as I first went to University to get a degree on it. Dad, thanks for teaching me the value of books and a solid right hook. To my other Dad, thank you for teaching me the virtue of patience (yes, I know, I am still working on that one). -

THE JOURNAL of the ASSOCIATION of ANGLICAN MUSICIANS

THE JOURNAL of the ASSOCIATION OF ANGLICAN MUSICIANS AAM: SERVING THE EPSICOPAL CHURCH REPRINTED FROM VOLUME 29, NUMBER 3 (MARCH 2020) BY PERMISSION. Lambeth Conference Worship and Music: The Movement Toward Global Hymnody (Part I) MARTY WHEELER BURNETT, D.MIN. Since 1867, bishops in the Anglican Communion have A tradition of daily conference worship also developed, gathered periodically at the invitation of the Archbishop including morning Eucharist and Evening Prayer. During the of Canterbury. These meetings, known as Lambeth 1958 Lambeth Conference, The Church Times reported that: Conferences, have occurred approximately every ten years The Holy Communion will be celebrated each morning with the exception of wartime. A study of worship at the at 8:00 a.m. and Evensong said at 7:00 p.m. for those Lambeth Conferences provides the equivalent of “time-lapse staying in the house [Lambeth Palace]. In addition to photography”—a series of historical snapshots representative these daily services, once a week there will be a choral of the wider church over time. As a result, these decennial Evensong sung by the choirs provided by the Royal conferences provide interesting data on the changes in music School of Church Music, whose director, Mr. Gerald and liturgy throughout modern church history. Knight, is honorary organist to Lambeth Chapel. In 2008, I was privileged to attend the Lambeth The 1968 Lambeth Conference was the first and only Conference at the University of Kent, Canterbury, from July conference to offer an outdoor Eucharist in White City 16 through August 3. As a bishop’s spouse at the time, I was Stadium, located on the outskirts of London, at which 15,000 invited to participate in the parallel Spouses Conference. -

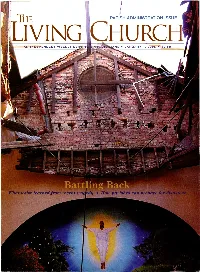

PARISH ADMINISTRATION ISSUE 1Llving CHURC----- 1-.··,.:, I

1 , THE PARISH ADMINISTRATION ISSUE 1llVING CHURC----- 1-.··,.:, I, ENDURE ... EXPLORE YOUR BEST ACTIVE LIVING OPTIONS AT WESTMINSTER COMMUNITIES OF FLORIDA! 0 iscover active retirement living at its finest. Cf oMEAND STAY Share a healthy lifestyle with wonderful neighbors on THREE DAYS AND TWO any of our ten distinctive sun-splashed campuses - NIGHTS ON US!* each with a strong faith-based heritage. Experience urban excitement, ATTENTION:Episcopalian ministers, missionaries, waterfront elegance, or wooded Christian educators, their spouses or surviving spouses! serenity at a Westminster You may be eligible for significant entrance fee community - and let us assistance through the Honorable Service Grant impress you with our signature Program of our Westminster Retirement Communities LegendaryService TM. Foundation. Call program coordinator, Donna Smaage, today at (800) 948-1881 for details. *Transportation not included. Westminster Communities of Florida www.WestminsterRetirement.com Comefor the Lifestyle.Stay for a Lifetime.T M 80 West Lucerne Circle • Orlando, FL 32801 • 800.948.1881 The objective of THELIVI N G CHURCH magazine is to build up the body of Christ, by describing how God is moving in his Church ; by reporting news of the Church in an unbiased manner; and by presenting diverse points of view. THIS WEEK Features 16 2005 in Review: The Church Begins to Take New Shape 20 Resilient People Coas1:alChurches in Mississippi after Hurricane Katrina BYHEATHER F NEWfON 22 Prepare for the Unexpected Parish sUIVivalcan hinge on proper planning BYHOWARD IDNTERTHUER Opinion 24 Editor's Column Variety and Vitality 25 Editorials The Holy Name 26 Reader's Viewpoint Honor the Body BYJONATHAN B . -

The Chicago-Lambeth Quadrilateral: Development in an Anglican Approach to Christian Unity

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Electrical and Computer Engineering Faculty Research and Publications/College of Engineering This paper is NOT THE PUBLISHED VERSION; but the author’s final, peer-reviewed manuscript. The published version may be accessed by following the link in the citation below. Journal of Ecumenical Studies, Vol. 33, No. 4 (Fall 1996): 471-486. Publisher link. This article is © University of Pennsylvania Press and permission has been granted for this version to appear in e- Publications@Marquette. University of Pennsylvania Press does not grant permission for this article to be further copied/distributed or hosted elsewhere without the express permission from University of Pennsylvania Press. THE CHICAGO-LAMBETH QUADRILATERAL: DEVELOPMENT IN AN ANGLICAN APPROACH TO CHRISTIAN UNITY Robert B. Slocum Theology, Marquette University, Milwaukee, WI PRECIS The Chicago-Lambeth Quadrilateral has served as the primary reference point and working document of the Anglican Communion for ecumenical Christian reunion. It identifies four essential elements for Christian unity in terms of scriptures, creeds, sacraments, and the Historic Episcopate. The Quadrilateral is based on the ecumenical thought and leadership of William Reed Huntington, an Episcopal priest who proposed the Quadrilateral in his book The Church.Idea:/In Essay toward Unity (1870) and who was the moving force behind approval of the Quadrilateral by the House of Bishops of the 1886 General Convention of the Protestant Episcopal Church. It was subsequently approved with modifications by the Lambeth Conference of 1888 and finally reaffirmed in its Lambeth form by the General Convention of the Episcopal Church in 1895. The Quadrilateral has been at the heart of Anglican ecumenical discussions and relationships since its approval Interpretation of the meaning of the Quadrilateral has undergone considerable development in its more than 100-year history. -

Missional Imperatives Archbishop Gomez

Missional Imperatives for the Anglican Church in the Caribbean The Most Rev. Drexel Gomez, Retired Archbishop of the West Indies Introduction The Church in The Province Of The West Indies (CPWI) is a member church of the Anglican Communion (AC). The AC is comprised of thirty-eight (38) member churches throughout the global community, and constitutes the third largest grouping of Christians in the world, after the Roman Catholic Communion, and the Orthodox Churches. The AC membership is ordinarily defined by churches being in full communion with the See of Canterbury, and which recognize the Archbishop of Canterbury as Primus Inter Pares (Chief Among Equals) amongst the Primates of the member churches. The commitment to the legacy of Apostolic Tradition, Succession, and Progression serves to undergird not only the characteristics of Anglicanism itself, provides the ongoing allegiance to some Missional Imperatives, driven and sustained by God’s enlivening Spirit. Anglican Characteristics Anglicanism has always been characterized by three strands of Christian emphases – Catholic, Reformed, and Evangelical. Within recent times, the AC has attempted to adopt specific methods of accentuating its Evangelical character for example by designating a Decade of Evangelism. More recently, the AC has sought to provide for itself a new matrix for integrating its culture of worship, work, and witness in keeping with its Gospel proclamation and teaching. The AC more recently determined that there should also be a clear delineation of some Marks of Mission. It agreed eventually on what it has termed the Five Marks of Mission. They are: (1) To proclaim the Good News of the Kingdom; (2) To teach, baptize and nurture new believers; (3) To respond to human need by loving service; (4) To seek to transform unjust structures in society to challenge violence of every kind and to pursue peace and reconciliation; (5) To strive to safeguard the integrity of creation, and sustain and renew the life of the earth. -

Bishop Dennis Commissioned by the Pope and the Archbishop of Canterbury and “Sent Out” for Mission

NORTHERN WITNESS What are those New Bible study humans doing? Page 7 Page 3 Advent events Page 5 NOVEMBER 2016 A SECTION OF THE ANGLICAN JOURNAL ᑯᐸᒄ ᑲᑭᔭᓴᐤ ᐊᔭᒥᐊᐅᓂᒡ • ANGLICAN DIOCESE OF QUEBEC • DIOCÈSE ANGLICAN DE QUÉBEC Bishop Dennis commissioned by the Pope and the Archbishop of Canterbury and “sent out” for mission By Gavin DrakeACNS The commissioning Drainville and Roman Catholic and sending out came in the Archbishop of Regina, Donald The Archbishop of setting of a Vespers service, Bolen. Bishop Bolen has been Canterbury Justin Welby and led jointly by Pope Francis Pope Francis have commis- and Archbishop Welby, at the sioned 19 pairs of Anglican Church of Saint Gregory on and Roman Catholic bishops the Caelian Hill in Rome. from across the world to take The service was one part in united mission in their of the highlights of an ecu- local areas. The bishops, se- menical summit organised lected by the International by Iarccum to mark the 50th Anglican Roman Catholic anniversary of the meeting Commission for Unity and between Pope Paul VI and Mission (Iarccum) were “sent Archbishop Michael Ramsey out” for mission together by in 1966 – the first such public the Pope and Archbishop from Archbishop Justin Welby and Pope Francis commis- meeting between a Pope and the same church were Pope sion and send out 19-pairs of bishops for joint an Archbishop of Canterbury Gregory sent Saint Augustine mission Photo Credit: Vatican Television since the Reformation. The to evangelise the English in God,” Pope Francis told the you’. We too, send you out summit, which began at the Archbishop of Regina, the sixth Century. -

St. Patrick's Church

There was only one church in the entire central area of Governor’s Harbour. On Archdeacon Jrew’s visitation in May and June of 1847, he administered the sacrament for the St. Patrick’s Church first time in this church. The population then made a tremendous increase and the people of Governor’s Harbour, Eleuthera, Bahamas this area made a request that Fr. Richard Chambers who was the priest of five islands, be restricted to Eleuthera alone. During this time, however, there was a terrible hurricane and the church was completely destroyed, creating the need for a new church. On January 2, 1892, the new Anglican Church that residents of Governor’s Harbour had so long waited and worked for was finally begun. The site was laid out, the foundation dug out, and willing hands were sent to work. The Church’s outside measurements are 76 ft. by 40 ft.; because of the walls being 2 ft. thick, the inside measurements are 72 ft. by 35 ft. The foundation wall is 3 ft. thick. Hence the work was expensive but necessary in case of hurricanes or other bad types of weather. The cornerstone of the new church had now been laid under the leadership of Fr. Smith (who served 1886-1903). On completion in 1893 and consecration Nov. 26, 1894 by Lord Bishop Churton, Fr. Browne, Fr. Blum and the current Rector, Fr. Smith, this building was described as “A very substantial, large and beautiful church.” The cost was about £1,000, the money being gathered from the previous eight years by the means of church sales, collections, donations from residents of Governor’s Harbour and from friends in England. -

Laudato Si’ , That Wealthi - Ecological Crisis,” and While Ecol - August 26

Single Issue: $1.00 Publication Mail Agreement No. 40030139 CATHOLIC JOURNAL Vol. 93 No. 6 June 24, 2015 Summer schedule God’s creation is ‘crying out with pain’ The Prairie Messenger pub - lishes every By Cindy Wooden Situating mate right” to private property, second week ecology but that right is never “absolute or in July and VATICAN CITY (CNS) — The firmly with - inviolable,” since the goods of the takes a three- earth, which was created to sup - in Catholic earth were created to benefit all. week sum - port life and give praise to God, is social teach - Regarding pollution and envi - crying out with pain because ing, Pope ronmental destruction in general, mer vacation in August. human activity is destroying it, Francis not he says it is important to acknowl - Summer issues will be dated Pope Francis says in his long- only insists edge “the human origins of the July 1, July 15, July 29 and awaited encyclical, Laudato Si’ , that wealthi - ecological crisis,” and while ecol - August 26. on Care for Our Common Home.” er nations ogy is not only a religious con - All who believe in God and all — who con - cern, those who believe in God Bred in the bone people of goodwill have an obli - tributed should be especially passionate on gation to take steps to mitigate cli - more to the subject because they profess Grace must be bred in the mate change, clean the land and despoiling the divine origin of all creation. bone, says the seas, and start treating all of the earth — Pope Francis singles out for spe - Gordon creation — including poor people must bear cial praise Orthodox Ecumenical Smith, pres - — with respect and concern, he more of the Patriarch Bartholomew of Constan - ident of says in the document released at costs of ti nople, who has made environ - Ambrose the Vatican June 18. -

Lambeth Conference Resolutions Archive

Resolutions Archive from 1867 Published by the Anglican Communion Office © 2005 Anglican Consultative Council Index of Resolutions from 1867 Lambeth Conference Resolutions Archive Index of Resolutions from 1867 Resolution 1 Resolution 2 Resolution 3 Resolution 4 Resolution 5 Resolution 6 Resolution 7 Resolution 8 Resolution 9 Resolution 10 Resolution 11 Resolution 12 Resolution 13 - 1 - Resolutions from 1867 Resolution 1 That it appears to us expedient, for the purpose of maintaining brotherly intercommunion, that all cases of establishment of new sees, and appointment of new bishops, be notified to all archbishops and metropolitans, and all presiding bishops of the Anglican Communion. Resolution 2 That, having regard to the conditions under which intercommunion between members of the Church passing from one distant diocese to another may be duly maintained, we hereby declare it desirable: 1. That forms of letters commendatory on behalf of clergymen visiting other dioceses be drawn up and agreed upon. 2. That a forms of letters commendatory for lay members of the Church be in like manner prepared. 3. That His Grace the Lord Archbishop of Canterbury be pleased to undertake the preparation of such forms. Resolution 3 That a committee be appointed to draw up a pastoral address to all members of the Church of Christ in communion with the Anglican branch of the Church Catholic, to be agreed upon by the assembled bishops, and to be published as soon as possible after the last sitting of the Conference. Resolution 4 That, in the opinion of this Conference, unity in faith and discipline will be best maintained among the several branches of the Anglican Communion by due and canonical subordination of the synods of the several branches to the higher authority of a synod or synods above them. -

Welcoming Those Coming to the UK for the Lambeth Conference

Who’s coming to our Diocese? We anticipate hosting bishops and their spouses from around the world, including our diocesan link bishops from the Dioceses of Nandyal in India and Kimberley and Kuruman in Southern Africa, our Mothers Union link bishops from Kinshasa in the Democratic Republic of Congo and Victoria Nyanza in Tanzania, and bishops from North Kivu in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Christ the King in South Africa, Maseno South in Kenya, Temuco in Chile, Tennessee and Upper South Bishop Achille Carolina in the USA, and Northern Territory, Willochra and North Queensland in Australia. We’ll be introducing our guests through interviews after Easter – meet them on our website: oxford.anglican.org/big-hello The programme Wednesday 15 July Participants to be in the country by this date Thursday 16 July Gathering for bishops with Bishop Steven Friday 17 July Sightseeing; themed evening events Saturday 18 July Evensong at Christ Church Cathedral Welcoming those Sunday 19 July Bishops attend the hosts’ churches; afternoon/evening deanery events coming to the UK for Monday 20/Tuesday 21 July Sightseeing and themed events Wednesday 22 July – Sunday 2 August The Lambeth Conference the Lambeth Conference For updates and full programme information visit oxford.anglican.org/big-hello 15-22 July 2020 An international Christian event How can I get involved? The Lambeth Conference is a once-a-decade event gathering bishops and Help with hospitality their spouses from across the Anglican Communion for prayer, Bible study, Volunteers can help with the programme at any time between 15–22 July. fellowship and dialogue on church and world issues. -

A Primer on the Government of the Episcopal Church and Its Underlying Theology

A Primer on the government of The Episcopal Church and its underlying theology offered by the Ecclesiology Committee of the House of Bishops Fall 2013 The following is an introduction to how and why The Episcopal Church came to be, beginning in the United States of America, and how it seeks to continue in “the faith once delivered to the saints” (Jude 3). Rooted in the original expansion of the Christian faith, the Church developed a distinctive character in England, and further adapted that way of being Church for a new context in America after the Revolution. The Episcopal Church has long since grown beyond the borders of the United States, with dioceses in Colombia, the Dominican Republic, Ecuador (Central and Litoral), Haiti, Honduras, Micronesia, Puerto Rico, Taiwan, Venezuela and Curacao, and the Virgin Islands, along with a Convocation of churches in six countries in Europe. In all these places, Episcopalians have adapted for their local contexts the special heritage and mission passed down through the centuries in this particular part of the Body of Christ. “Ecclesiology,” the study of the Church in the light of the self-revelation of God in Jesus Christ, is the Church’s thinking and speaking about itself. It involves reflection upon several sources: New Testament images of the Church (of which there are several dozen); the history of the Church in general and that of particular branches within it; various creeds and confessional formulations; the structure of authority; the witness of saints; and the thoughts of theologians. Our understanding of the Church’s identity and purpose invariably intersects with and influences to a large extent how we speak about God, Christ, the Spirit, and ourselves in God’s work of redemption. -

ACC Meeting Reveals Deeply Divided Anglican Communion

th Volume 1, Issue 14 18 May 2009 ACC Meeting Reveals Deeply Divided Anglican Communion The 14th meeting of the Anglican Consultative Council (ACC) concluded on 12th May in Kingston, Jamaica, Church of the Province of the West Indies, with little progress made on resolving the deep conflict in the Anglican Communion. The Church of Uganda is entitled to three delegates – a bishop, priest, and lay person – but was represented only by its lay delegate, Mrs. Jolly Babirukamu. The ACC meets approximately every two to three years as a consultative body of delegates from the 38 Provinces of the Anglican Communion. It is considered one of the four “Instruments of Communion” within the Anglican Communion. The other three are the Primates’ Meeting, the Lambeth Conference of Bishops, and the Archbishop of Canterbury, who is common to all of them. The formula for determining the number of delegates a Province is entitled to send to the ACC is a mystery. The wealthier, but small Western Provinces, are over-represented. Nigeria, for example, has more than 18 million active Anglicans and is entitled to three members on the ACC, while Canada, with perhaps less than 600,000 members and TEC, with approximately 800,000 active members, also have three members. The Rt. Rev. Paul Luzinda, Bishop of Mukono Diocese, is the Church of Uganda’s Bishop delegate to the ACC. He was, however, unable to attend the ACC because of a commitment to participate in the 40th anniversary celebration in the UK of the Church of Uganda and Bristol Diocese’s link relationship.