The Unicode Standard, Version 6.1 Copyright © 1991–2012 Unicode, Inc

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Indian Culture and Heritage

Website: iashelpdesk.in Whatsapp: 8586055783 DDCE/M.A Hist./Paper-VIII INDIAN CULTURE AND HERITAGE BY Dr. Binod Bihari Satpathy 0 Website: iashelpdesk.in Whatsapp: 8586055783 CONTENT INDIAN CULTURE AND HERITAGE Unit.No. Chapter Name Page No Unit-I. Indian Culture: An Introduction 1. Characteristics of Indian culture, Significance of Geography on Indian 02-25 Culture. 2. Society in India through ages- Ancient period- varna and jati, family and 26-71 marriage in india, position of women in ancient india, Contemporary period; caste system and communalism. 3. Religion and Philosophy in India: Ancient Period: Pre-Vedic and Vedic 72-108 Religion, Buddhism and Jainism, Indian philosophy – Vedanta and Mimansa school of Philosophy. Unit-II Indian Languages and Literature 1. Evolution of script and languages in India: Harappan Script and Brahmi 109-130 Script. 2. Short History of the Sanskrit literature: The Vedas, The Brahmanas and 131-168 Upanishads & Sutras, Epics: Ramayana and Mahabharata & Puranas. 3. History of Buddhist and Jain Literature in Pali, Prakrit and Sanskrit, 169-207 Sangama literature & Odia literature. Unit-III. A Brief History of Indian Arts and Architecture 1. Indian Art & Architecture: Gandhara School and Mathura School of Art; 208-255 Hindu Temple Architecture, Buddhist Architecture, Medieval Architecture and Colonial Architecture. 2. Indian Painting Tradition: ancient, medieval, modern indian painting and 256-277 odishan painting tradition 1. Performing Arts: Divisions of Indian classical music: Hindustani and 278-298 Carnatic, Dances of India: Various Dance forms: Classical and Regional, Rise of modern theatre and Indian cinema. Unit-IV. Spread of Indian Culture Abroad 1. Causes, Significance and Modes of Cultural Exchange - Through Traders, 299-316 Teachers, Emissaries, Missionaries and Gypsies 2. -

Ka И @И Ka M Л @Л Ga Н @Н Ga M М @М Nga О @О Ca П

ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 N3319R L2/07-295R 2007-09-11 Universal Multiple-Octet Coded Character Set International Organization for Standardization Organisation Internationale de Normalisation Международная организация по стандартизации Doc Type: Working Group Document Title: Proposal for encoding the Javanese script in the UCS Source: Michael Everson, SEI (Universal Scripts Project) Status: Individual Contribution Action: For consideration by JTC1/SC2/WG2 and UTC Replaces: N3292 Date: 2007-09-11 1. Introduction. The Javanese script, or aksara Jawa, is used for writing the Javanese language, the native language of one of the peoples of Java, known locally as basa Jawa. It is a descendent of the ancient Brahmi script of India, and so has many similarities with modern scripts of South Asia and Southeast Asia which are also members of that family. The Javanese script is also used for writing Sanskrit, Jawa Kuna (a kind of Sanskritized Javanese), and Kawi, as well as the Sundanese language, also spoken on the island of Java, and the Sasak language, spoken on the island of Lombok. Javanese script was in current use in Java until about 1945; in 1928 Bahasa Indonesia was made the national language of Indonesia and its influence eclipsed that of other languages and their scripts. Traditional Javanese texts are written on palm leaves; books of these bound together are called lontar, a word which derives from ron ‘leaf’ and tal ‘palm’. 2.1. Consonant letters. Consonants have an inherent -a vowel sound. Consonants combine with following consonants in the usual Brahmic fashion: the inherent vowel is “killed” by the PANGKON, and the follow- ing consonant is subjoined or postfixed, often with a change in shape: §£ ndha = § NA + @¿ PANGKON + £ DA-MAHAPRANA; üù n. -

An Introduction to Indic Scripts

An Introduction to Indic Scripts Richard Ishida W3C [email protected] HTML version: http://www.w3.org/2002/Talks/09-ri-indic/indic-paper.html PDF version: http://www.w3.org/2002/Talks/09-ri-indic/indic-paper.pdf Introduction This paper provides an introduction to the major Indic scripts used on the Indian mainland. Those addressed in this paper include specifically Bengali, Devanagari, Gujarati, Gurmukhi, Kannada, Malayalam, Oriya, Tamil, and Telugu. I have used XHTML encoded in UTF-8 for the base version of this paper. Most of the XHTML file can be viewed if you are running Windows XP with all associated Indic font and rendering support, and the Arial Unicode MS font. For examples that require complex rendering in scripts not yet supported by this configuration, such as Bengali, Oriya, and Malayalam, I have used non- Unicode fonts supplied with Gamma's Unitype. To view all fonts as intended without the above you can view the PDF file whose URL is given above. Although the Indic scripts are often described as similar, there is a large amount of variation at the detailed implementation level. To provide a detailed account of how each Indic script implements particular features on a letter by letter basis would require too much time and space for the task at hand. Nevertheless, despite the detail variations, the basic mechanisms are to a large extent the same, and at the general level there is a great deal of similarity between these scripts. It is certainly possible to structure a discussion of the relevant features along the same lines for each of the scripts in the set. -

Sacral Chakra

Tour of the Chakras Series: Sacral Chakra M a y 20 1 6 © 20 1 2 by Angelique M. Bouffiou V o lu me 1, Issue 3 MysticsAlchemy9. co m Mystic, Writer, Teacher Svadhishthana, the 2nd Chakra The sacral chakra is the second chakra dreams or plans can be made manifest counting from root to crown. This energy into reality. Therefore, it is ultimately center runs through the reproductive and sex important to keep this chakra in balance organs. The Sanskrit name is Svadhishthana. and harmonized. The element of this chakra is water, which is represented in the image, on the left, by the The root and sacral chakras are silver crescent moon. On each petal is a connected. Well, actually all the chakras are connected. However, an imbalance in syllable. The mantra Vam is written in the center. Chanting the syllables "Ba, Bha, Ma, the root can offset the sacral easily. You Ya, Ra La" or the mantra "Vam", can assist in will also learn how to recognize imbalance Svadhisthana chakra unfolding and balancing this chakra. and how to harmonize these energies for 2nd chakra your empowerment. The energy that runs through this chakra is If you are having trouble manifesting the sexual creative energy, not the sexual OR those dreams or plans, it may be that you creative energy. Sexual energy and creative are blocked by shame, doubt, guilt, fear or energy are one in the same. Whether you are a defunct story. Worry not! We will look Contents creating babies or a business, the focus is into some ways to clear these. -

Arquitetura Para Realidade Aumentada Em Plataformas Móveis

Computer on the Beach 2013 - Artigos Completos 167 Arquitetura para Realidade Aumentada em Plataformas Móveis Daniel Ricardo Batiston, Dalton Solano dos Reis!, Aurélio Hoppe! Departamento de Sistemas e Computação Universidade Regional de Blumenau (FURB) – Blumenau, SC – Brazil [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract. This article describes the architecture and development to built Augmented Reality applications on mobile device platforms. The architecture is based on OpenGL ES 1.1 library to create and draw some virtual objects, it uses also geolocation and features as images captured by camera, accelerometers and magnetometers to provide the user interaction. At the end we present an application example along with performance results running on iOS platfoms' devices, achieving acceptable results. Resumo. Este artigo descreve a arquitetura e o desenvolvimento de uma biblioteca para a criação de aplicativos de Realidade Aumentada em plataformas móveis. Baseada na biblioteca OpenGL ES 1.1 para a construção e desenho de objetos virtuais, é utilizado também geolocalização e recursos como captura de imagens da câmera, acelerômetros e magnetômetros dos dispositivos para prover a interação com o usuário. Ao final é apresentado um exemplo de aplicação juntamente com os resultados de avaliações de desempenho feitas em dispositivos da plataforma iOS, atingindo resultados aceitáveis. 1.Introdução A Realidade Aumentada (RA) consiste numa interface computacional avançada, que promove em tempo real a exibição de elementos virtuais sobre a visualização de determinadas cenas do mundo real, oferecendo um forte potencial a aplicações industriais e educacionais, devido ao alto grau de interatividade [Kirner 2004]. Áreas como construção civil, jogos, medicina, publicidade, design, entre outras, vem aplicando este conceito para o aperfeiçoamento de suas técnicas. -

UTC L2/20-061 2020-01-28 Universal Multiple-Octet Coded Character Set International Organization for Standardization Organisation Internationale De Normalisation

UTC L2/20-061 2020-01-28 Universal Multiple-Octet Coded Character Set International Organization for Standardization Organisation Internationale de Normalisation Doc Type: Working Group Document Title: Final Proposal to encode Western Cham in the UCS Source: Martin Hosken Status: Individual contribution Action: For consideration by UTC and ISO Date: 2020-01-28 Executive Summary. This proposal is to add 97 characters to a block: 1E200-1E26F in the supplementary plane, named Western Cham. In addition, 1 character is proposed for inclusion in the Arabic Extended A block: 08A0-08FF. The proposal is a revision of L2/19-217r3. A revision history is given at the end of the main text of this document. Introduction. Eastern Cham is already encoded in the range AA00-AA5F. As stated in N4734, Western Cham while closely related to Eastern Cham, is sufficiently different in style for Eastern Cham characters in plain text to be unintelligible to Western Cham readers and therefore a separate block is required. As such, the proposal to encode Western Cham in a separate block from (Eastern) Cham can be considered a disunification. But since Western Cham was never supported in the (Eastern) Cham block, it can be argued that this is a proposal for a new script. This is further discussed in the section on disunification. The Western Cham encoding follows the same encoding model as for (Eastern) Cham. There is no halant or virama that calls for a Brahmic model. The basic structure is a base character followed by a sequence of marks as described in the section on combining orders. -

Balinese Romanization Table

Balinese Principal consonants1 (h)a2 ᬳ ᭄ᬳ na ᬦ ᭄ᬦ ca ᬘ ᭄ᬘ᭄ᬘ ra ᬭ ᭄ᬭ ka ᬓ ᭄ᬓ da ᬤ ᭄ᬤ ta ᬢ ᭄ᬢ sa ᬲ ᭄ᬲ wa ᬯ la ᬮ ᭄ᬙ pa ᬧ ᭄ᬧ ḍa ᬟ ᭄ᬠ dha ᬥ ᭄ᬟ ja ᬚ ᭄ᬚ ya ᬬ ᭄ᬬ ña ᬜ ᭄ᬜ ma ᬫ ᭄ᬫ ga ᬕ ᭄ᬕ ba ᬩ ᭄ᬩ ṭa ᬝ ᭄ᬝ nga ᬗ ᭄ᬗ Other consonant forms3 na (ṇa) ᬡ ᭄ᬡ ca (cha) ᭄ᬙ᭄ᬙ ta (tha) ᬣ ᭄ᬣ sa (śa) ᬱ ᭄ᬱ sa (ṣa) ᬰ ᭄ᬰ pa (pha) ᬨ ᭄ᬛ ga (gha) ᬖ ᭄ᬖ ba (bha) ᬪ ᭄ᬪ ‘a ᬗ᬴ ha ᬳ᬴ kha ᬓ᬴ fa ᬧ᬴ za ᬚ᬴ gha ᬕ᬴ Vowels and other agglutinating signs4 5 a ᬅ 6 ā ᬵ ᬆ e ᬾ ᬏ ai ᬿ ᬐ ĕ ᭂ ö ᭃ i ᬶ ᬇ ī ᬷ ᬈ o ᭀ ᬑ au ᭁ ᬒ u7 ᬸ ᬉ ū ᬹ ᬊ ya, ia8 ᭄ᬬ r9 ᬃ ra ᭄ᬭ rĕ ᬋ rö ᬌ ᬻ lĕ ᬍ ᬼ lö ᬎ ᬽ h ᬄ ng ᬂ ng ᬁ Numerals 1 2 3 4 5 ᭑ ᭒ ᭓ ᭔ ᭕ 6 7 8 9 0 ᭖ ᭗ ᭘ ᭙ ᭐ 1 Each consonant has two forms, the regular and the appended, shown on the left and right respectively in the romanization table. The vowel a is implicit after all consonants and consonant clusters and should be supplied in transliteration, unless: (a) another vowel is indicated by the appropriate sign; or (b) the absence of any vowel is indicated by the use of an adeg-adeg sign ( ). (Also known as the tengenen sign; ᭄ paten in Javanese.) 2 This character often serves as a neutral seat for a vowel, in which case the h is not transcribed. -

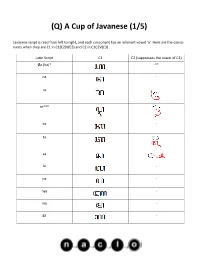

Q) a Cup of Javanese (1/5

(Q) A Cup of Javanese (1/5) Javanese script is read from left to right, and each consonant has an inherent vowel ‘a’. Here are the conso- nants when they are C1 in C1(C2)V(C3) and C2 in C1C2V(C3). Latin Script C1 C2 (suppresses the vowel of C1) Øa (ha)* -** na - ra re*** ka - ta sa la - pa - nya - ma - ga - (Q) A Cup of Javanese (2/5) Javanese script is read from left to right, and each consonant has an inherent vowel ‘a’. Here are the conso- nants when they are C1 in C1(C2)V(C3) and C2 in C1C2V(C3). Latin Script C1 C2 (suppresses the vowel of C1) ba nga - *The consonant is either ‘Ø’ (no consonant) or ‘h,’ but the problem contains only the former. **The ‘-’ means that the form exists, but not in this problem. ***The CV combination ‘re’ (historical remnant of /ɽ/) has its own special letters. ‘ng,’ ‘h,’ and ‘r’ must be C3 in (C1)(C2)VC3 before another C or at the end of a word. All other consonants after V must be C1 of the next syllable. If these consonants end a word, a ‘vowel suppressor’ must be added to suppress the inherent ‘a.’ Latin Script C3 -ng -h -r -C (vowel suppressor) Consonants can be modified to change the inherent vowel ‘a’ in C1(C2)V(C3). Latin Script V* e** (Q) A Cup of Javanese (3/5) Latin Script V* i é u o * If C2 is on the right side of C1, then ‘e,’ ‘i,’ and ‘u’ modify C2. -

Final Proposal to Encode Nandinagari in Unicode

L2/17-162 2017-05-05 Final proposal to encode Nandinagari in Unicode Anshuman Pandey [email protected] May 5, 2017 1 Introduction This is a proposal to encode the Nandinagari script in Unicode. It supersedes the following documents: • L2/13-002 “Preliminary Proposal to Encode Nandinagari in ISO/IEC 10646” • L2/16-002 “Proposal to encode the Nandinagari script in Unicode” • L2/16-310 “Proposal to encode the Nandinagari script in Unicode” • L2/17-119 “Towards an encoding model for Nandinagari conjuncts” It incorporates comments regarding previous proposals made in: • L2/16-037 “Recommendations to UTC #146 January 2016 on Script Proposals” • L2/16-057 “Comments on L2/16-002 Proposal to encode Nandinagari” • L2/16-216 “Recommendations to UTC #148 August 2016 on Script Proposals” • L2/17-153 “Recommendations to UTC #151 May 2017 on Script Proposals” • L2/17-117 “Proposal to encode a nasal character in Vedic Extensions” Major changes since L2/16-310 include: • Expanded description of the headstroke and its behavior (see section 3.2). • Clarification of encoding model for consonant conjuncts (see section 5.4). • Removal of digits and proposed unification with Kannada digits (see section 4.9). • Re-analysis of ‘touching’ conjuncts as variant forms that may be controlled using fonts. • Removal of ardhavisarga and other characters that require additional research (see section 4.10). • Identification of a pr̥ ṣṭhamātrā, which is not included in the proposed repertoire (see section 4.10). • Proposed reallocation of a Vedic nasal letter to the ‘Vedic Extensions’ block (see L2/17-117). • Revision of Indic position category for vowel signs. -

General Historical and Analytical / Writing Systems: Recent Script

9 Writing systems Edited by Elena Bashir 9,1. Introduction By Elena Bashir The relations between spoken language and the visual symbols (graphemes) used to represent it are complex. Orthographies can be thought of as situated on a con- tinuum from “deep” — systems in which there is not a one-to-one correspondence between the sounds of the language and its graphemes — to “shallow” — systems in which the relationship between sounds and graphemes is regular and trans- parent (see Roberts & Joyce 2012 for a recent discussion). In orthographies for Indo-Aryan and Iranian languages based on the Arabic script and writing system, the retention of historical spellings for words of Arabic or Persian origin increases the orthographic depth of these systems. Decisions on how to write a language always carry historical, cultural, and political meaning. Debates about orthography usually focus on such issues rather than on linguistic analysis; this can be seen in Pakistan, for example, in discussions regarding orthography for Kalasha, Wakhi, or Balti, and in Afghanistan regarding Wakhi or Pashai. Questions of orthography are intertwined with language ideology, language planning activities, and goals like literacy or standardization. Woolard 1998, Brandt 2014, and Sebba 2007 are valuable treatments of such issues. In Section 9.2, Stefan Baums discusses the historical development and general characteristics of the (non Perso-Arabic) writing systems used for South Asian languages, and his Section 9.3 deals with recent research on alphasyllabic writing systems, script-related literacy and language-learning studies, representation of South Asian languages in Unicode, and recent debates about the Indus Valley inscriptions. -

Iso/Iec Jtc1/Sc2/Wg2 N3383r L2/08-050R

ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 N3383R L2/08-050R 2008-03-06 Universal Multiple-Octet Coded Character Set International Organization for Standardization Organisation internationale de normalisation Международная организация по стандартизации Doc Type: Working Group Document Title: Summary proposal to encode characters for Vedic in the BMP of the UCS Source: Ireland and UC Berkeley Script Encoding Initiative (Universal Scripts Project) Authors: Michael Everson and Peter Scharf Status: National Body and Liaison Contribution Action: For consideration by JTC1/SC2/WG2 and UTC Replaces: N3366 Date: 2008-03-06 1. Introduction. This document reflects the consensus achieved after intense discussion of the Vedic characters proposed by CDAC in India on the one hand by Everson, Scharf, et al. on the other, in a large number of documents presented since 2006. The repertoire given here comprises a set of characters which all parties agree should be encoded to enable India and Western Vedic specialists to represent the texts and critical apparatus of this important field of study. A few outstanding issues remain but it is agreed that these might be left for further study. The characters presented in this document are, in our opinion, well-documented and appropriate for encoding. It is worthwhile reviewing some of the issues which were previously controversial. 2. PRISHTHAMATRA E. It is our view that the best way to handle this is to encode a single vowel sign for e that can be used in combination with other characters for o, ai, and au, as presented in N3235R. We do not believe that the spoofing danger of this character is as great as has been suggested: one could recommend to registrars, for instance, that the character can be restricted from use in IDN. -

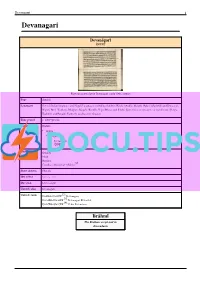

Devanagari 1 Devanagari

Devanagari 1 Devanagari Devanāgarī देवनागरी Rigveda manuscript in Devanagari (early 19th century) Type abugida Languages Several Indian languages and Nepali Languages, including Sanskrit, Hindi, Awadhi, Marathi, Pahari (Garhwali and Kumaoni), Nepali, Bhili, Konkani, Bhojpuri, Magahi, Kurukh, Nepal Bhasa, and Sindhi. Sometimes used to write or transliterate Sherpa, Kashmiri and Punjabi. Formerly used to write Gujarati. Time period c. 1200–present Parent systems Brāhmī •• Gupta •• Nāgarī • Devanāgarī देवनागरी Child systems Gujarati Moḍī Ranjana [1] Canadian Aboriginal syllabics Sister systems Sharada ISO 15924 Deva, 315 Direction Left-to-right Unicode alias Devanagari Unicode range [2] U+0900–U+097F Devanagari, [3] U+A8E0–U+A8FF Devanagari Extended, [4] U+1CD0–U+1CFF Vedic Extensions Brāhmī The Brahmic script and its descendants Devanagari 2 Devanagari (/ˌdeɪvəˈnɑːɡəriː/; Hindustani: [d̪eːʋˈnaːɡri]; देवनागरी devanāgarī — a compound of "deva" [देव] and "nāgarī" [नागरी]), also called Nagari (Nāgarī, नागरी, the name of its parent writing system), is an abugida alphabet of India and Nepal. It is written from left to right, does not have distinct letter cases, and is recognisable (along with most other North Indic scripts, with few exceptions like Gujarati and Oriya) by a horizontal line that runs along the top of full letters. Since the 19th century, it has been the most commonly used script for Sanskrit. Devanagari is used to write Standard Hindi, Marathi, Nepali along with Awadhi, Bodo, Bhojpuri, Gujari, Pahari, (Garhwali and Kumaoni), Konkani, Magahi, Maithili, Marwari, Bhili, Newar, Santhali, Tharu, Devanagari used in Melbourne Australia to and sometimes Sindhi, Dogri, Sherpa, Kashmiri and Punjabi. It was communicate in an advertisement formerly used to write Gujarati.