Arxiv:2007.11266V1 [Astro-Ph.GA] 22 Jul 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Summer Programming

TV LAND BRINGS THE HEAT WITH A SUMMER LINE-UP FULL OF FUNNIEST STARS AND SITCOMS The Home of TV’s Favorite Sitcoms Sizzles With Original Series, A Special Presentation With Shirley MacLaine, And The Launch Of ‘That ‘70s Show” New York, NY – May 24, 2012 – TV Land’s summer programming is hotter than ever! Beginning June 1, the network is introducing a new summer line-up full of laughs with two nights of original sitcoms, including “The Soul Man,” starring Cedric “The Entertainer” and Niecy Nash, returning series “The Exes,” starring Donald Faison, Wayne Knight, David Alan Basche, Kelly Stables and Kristen Johnston and “Retired at 35” starring George Segal, Jessica Walter, Marissa Jaret Winokur, Johnathan McClain and Josh McDermitt. June on TV Land will also feature “TV Land Presents: The AFI Life Achievement Award Honoring Shirley MacLaine” and the launch of acquisition “That ‘70s Show.” Below is a detailed look at TV Land’s summer programming: ORIGINAL PROGRAMMING “The Soul Man” SERIES PREMIERE: Wednesday, June 20 at 10pm ET/PT “The Soul Man” stars Cedric “The Entertainer” and Niecy Nash and revolves around R&B superstar-turned-minister Reverend Boyce “The Voice” Ballentine (played by Cedric). Though he’s used to living in Las Vegas at the top of the music charts, he gets “the calling” and decides to relocate to St. Louis with his wife, Lolli (Nash) and his daughter, Lyric (Jazz Raycole), to take over the preaching duties in his father’s church. However, his family is not exactly eager to give up the fabulous superstar life for their new humble one. -

"SYDNEY to the MAX" Now in Its Third Season, Disney Channel's

"SYDNEY TO THE MAX" Now in its third season, Disney Channel's popular daughter/father comedy "Sydney to the Max" continues to strike the perfect balance of humor and heart while showcasing hilarious adventures about friendship, family and the twists and turns of growing up. Set in the present day with flashbacks to the 1990s, the live-action comedy follows outgoing middle schooler Sydney Reynolds who lives with her single dad Max in the house he grew up in, along with her free-spirited grandmother Judy. As Sydney navigates being a teenager alongside her bestie Olive, Max's flashbacks of his childhood with his best friend Leo parallel her adventures, illustrating how life's "growing pains" evolve but don't really change. Geared for Kids 6-11 and their families, the series delivers its boldest season yet as Sydney and her friends—as well as Young Max and Leo in the 90s—embark on eighth grade. Their worlds become a bit more complex as they take on challenging and relevant issues, including struggles with cultural identity, trying to fit in, coping with divorce, and the impact of microaggressions. Other relatable stories rounding out the new season touch on the pitfalls of social media, the funny moments when dealing with your crush, and trying to bounce back from having to throw a virtual bat mitzvah get-together instead of your dream celebration. No matter the decade, there is never a dull moment in the Reynolds' household as Sydney becomes even more determined to discover and express her authentic self, and Young Max finds his stride and a hint of his future in the 90s. -

Jaime Pressly Cast in New Tv Land Pilot “Jennifer Falls”

JAIME PRESSLY CAST IN NEW TV LAND PILOT “JENNIFER FALLS” New York, NY – August 5, 2013 – Emmy® Award-winning actress Jaime Pressly has been cast in the lead role for TV Land’s new pilot “Jennifer Falls,” it was announced today by Keith Cox, Executive Vice President of Development and Original Programming for the network. Pressly, best known for her work on the NBC series “My Name is Earl,” will play the lead character, Jennifer Doyle, in this multi-camera pilot. “Jennifer Falls" revolves around a career woman and mother (Pressly) who must move back in with her own mom after being let go from her high-powered, six-figure salary job. With her teenage daughter in tow, Jennifer has to face her new life, trying to reconnect with old friends in her hometown and making ends meet as a waitress in her brother’s bar. “It’s amazing to have someone like Jaime Pressly on board for ‘Jennifer Falls,'” said Cox. “We loved this script from the moment we read it, and Jaime just brings the role to life perfectly.” The pilot is written, created and executive produced by Matthew Carlson (“The Wonder Years,” “Malcolm in the Middle”), with Michael Hanel and Mindy Schultheis (“Reba,” “The Exes”) also serving as executive producers. TV Land's current line-up of original sitcoms airs Wednesdays at 10pm ET/PT and includes the hit series "Hot in Cleveland," "The Exes" and "The Soul Man." The series have received several awards and accolades including two 2013 Creative Arts Emmy® nominations: one for "Hot in Cleveland" and the other for "The Exes." All of these series star pop culture icons and fan favorites including Betty White, Valerie Bertinelli, Wendie Malick, Jane Leeves, Kristen Johnston, Donald Faison, Wayne Knight, David Alan Basche, Kelly Stables, Cedric "The Entertainer," Niecy Nash and Wesley Jonathan. -

Elle Alexander

ELLE ALEXANDER Stuntwomen’s Association of Motion Pictures STUNTWOMAN/ACTRESS HEIGHT: 5’11” WEIGHT: 140 www.ellealexander.com SAG/AFTRA EYES: BROWN stunt/acting demo reels SERVICE: (818) 762-0907 HAIR: LT BROWN/DK BLONDE iStunt / Stuntphone FILM/TELEVISION STUNT COORDINATOR ANGIE TRIBECA Stunt Actress Erik Solky THE GOLDBERGS Stunt Double (Wendy McLendon-Covey) Marc Scizak/Keith Campbell *CONAN Stunt Actress Tony Angelotti/Mark Wagner *THE HAVES AND HAVE NOTS Stunt Double (Allison McAtee) Yan Dron/Greg Sproles *BATTLE CREEK Stunt Double (Janet McTeer) Jim Vickers GLEE Stunt Double (Jane Lynch) Jimmy Sharp/Carrick O’Quinn SELFIE Stunt Double (Karen Gillan) Larry Nicholas *CLUB SANTINO Stunt Actor (Series) Elle Alexander JENNIFER FALLS Stunt Double (Missi Pyle) Ben Scott YOU’RE THE WORST Stunt Double (Caitlin Kimball) Greg Fitzpatrick SALEM Stunt Double (Diane Salinger) Jim Henry GRIMM Stunt Double (Anne Dudek) Matt Taylor ALEXANDER & THE TERRIBLE DAY Stunt Double (Jennifer Coolidge) Garrett Warren BOUNTY HUNTER (Pilot) Stunt Double (Geena Davis) Kevin Jackson *THE EXES Stunt Double (Kristen Johnston) Danny Wayne TRUE BLOOD Stunt Double (Melanie Camp) Hiro Koda *SHAMELESS Stunt Actor/Stunt Dbl. (Louise Fletcher) Laura Albert I REALLY HATE MY EX Stunt Coordinator Elle Alexander VAMPS Stunt Double (Sigourney Weaver) Dan Lemieux THE SUITE LIFE ON DECK Stunt Double (Lisa Wyatt) Rex Reddick BIG TIME RUSH Stunt Actor Vince Deadrick Jr. SAN FRANCISCO, 2177 Stunt Actor Steve Schriver YOU AGAIN Stunt Double (Sigourney Weaver) Scott Rogers PAUL Stunt Double (Sigourney Weaver) Darrin Prescott ZOMBIELAND Stunt Actor George Aguilar ICARLY Stunt Double Vince Deadrick Jr. FLEECE Stunt Double (Melissa Peterman) Calvin Brown CHOCOLATE NEWS Stunt Actor Julius LeFlore MISS NOBODY Stunt Dbl.(Leslie Bibb/Missi Pyle) Kurt Bryant SUPERHERO! Utility Stunts Charlie Croughwell NUMB3RS Stunt Actor Jim Vickers MY NAME IS EARL Stunt Actor Al Jones HEROES / THE CLEANER Stunt Dbl. -

DGA's 2014-2015 Episodic Television Diversity Report Reveals

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: Lily Bedrossian August 25, 2015 (310) 289-5334 DGA’s 2014-2015 Episodic Television Diversity Report Reveals: Employer Hiring of Women Directors Shows Modest Improvement; Women and Minorities Continue to be Excluded In First-Time Hiring LOS ANGELES – The Directors Guild of America today released its annual report analyzing the ethnicity and gender of directors hired to direct primetime episodic television across broadcast, basic cable, premium cable, and high budget original content series made for the Internet. More than 3,900 episodes produced in the 2014- 2015 network television season and the 2014 cable television season from more than 270 scripted series were analyzed. The breakdown of those episodes by the gender and ethnicity of directors is as follows: Women directed 16% of all episodes, an increase from 14% the prior year. Minorities (male and female) directed 18% of all episodes, representing a 1% decrease over the prior year. Positive Trends The pie is getting bigger: There were 3,910 episodes in the 2014-2015 season -- a 10% increase in total episodes over the prior season’s 3,562 episodes. With that expansion came more directing jobs for women, who directed 620 total episodes representing a 22% year-over-year growth rate (women directed 509 episodes in the prior season), more than twice the 10% growth rate of total episodes. Additionally, the total number of individual women directors employed in episodic television grew 16% to 150 (up from 129 in the 2013-14 season). The DGA’s “Best Of” list – shows that hired women and minorities to direct at least 40% of episodes – increased 16% to 57 series (from 49 series in the 2013-14 season period). -

Spotted.Yankton.Net...Upload & Share Your Photos for FREE...Purchase

PRESS & DAKOTAN n FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 7, 2014 PAGE 9B MONDAY PRIMETIME/LATE NIGHT FEBRUARY 10, 2014 3:00 3:30 4:00 4:30 5:00 5:30 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 12:00 12:30 1:00 1:30 BROADCAST STATIONS Curious Arthur Å WordGirl Wild Martha Nightly PBS NewsHour (N) (In Antiques Roadshow Antiques Roadshow Independent Lens The Red BBC Charlie Rose (N) (In Tavis Smi- The Mind Antiques Roadshow PBS George (DVS) Å (DVS) Kratts Å Speaks Business Stereo) Å “Detroit” (N) Å “Eugene, OR” Å Mississippi agency and Green World Stereo) Å ley (N) Å of a Chef “Detroit” Å KUSD ^ 8 ^ Report civil rights. (N) Show News Å KTIV $ 4 $ XXII Olympics Ellen DeGeneres News 4 News News 4 Ent XXII Winter Olympics Alpine Skiing, Freestyle Skiing, Short Track. Å News 4 XXII Olympics XXII Winter Olympics XXII Winter Olympics Judge Judge KDLT NBC KDLT The Big XXII Winter Olympics Alpine Skiing, Freestyle Skiing, Short Track. From Sochi, KDLT XXII Winter Olympics XXII Winter Olympics Alpine Skiing, Freestyle NBC Speed Skating, Biath- Judy Å Judy Å News Nightly News Bang Russia. Alpine skiing: women’s super combined; freestyle skiing; short track. (N News Å Short Track, Luge. Å Skiing, Short Track. (In Stereo) Å KDLT % 5 % lon. Å (N) Å News (N) (N) Å Theory Same-day Tape) (In Stereo) Å KCAU ) 6 ) Dr. Phil Å The Dr. Oz Show News at ABC News Inside The Bachelor (N) (In Stereo) Å Castle “Valkyrie” News Jimmy Kimmel Live Nightline Paid Inside ABC World News Dr. -

Ttu Aa0001 000391.Pdf

A Message From Your . Executive Secretary At the annual Council meeting held Nov. 6, 1953, the members voted to establish a "Texas Tech Day" in order to stimulate interest in Tech. The Executive Board of the Ex-Students Association was author ized to set the date and make plans. The purpose of a "Tech D ay,, is to bring exes together each year for common enjoyment of tradition and heritage of Texas Technological College. The meeting will be held each year on the Saturday following the first Monday in May. The date this year falls on May 8th. Know ledge that thousands of exes are meeting simultaneously will add signif icance. We are planning to have meetings only in towns in your district that have thirty or more exes living there. As this is the first year we have attempted to hold reunions over the country simultaneously, we feel that we cannot handle all towns to begin with. On the inside back cover of this magazine is a list of the towns in your district that we hope will hold meetings this year. You can be of invaluable service in helping make our first meeting of "Texas Tech Day" a success. Will you plan now to attend the meet ing in your city or the city nearest .you? If you do not know the person to contact in your· district, write this office for additional information. Since a wide time span is represented by our exes, programs are being planned with the thought of holding interest for all ex-students. -

December 1950

DECEMBER 1950 r ~ l l l ( [ t tf; Practical-Pretty-Per- ~ l fect - electric appliances will ~ I' score as Christmas gifts on all three counts. Used every day of the year, remembered every day of the year, [ electrical gifts will assure everyone on your gift list of a "Merry Christ- mas". r Toasters, waffle bakers, coffee makers, griddles, electric blankets, irons, electric shavers. Your local appliance dealer II has all these gift suggestions-and many others-on display. Give the gift that keeps on giving-an electric appliance. r SOUTHWESTERN I PUBLIC SERVICE t) COMPANY 26 YEARS OF GOOD CITIZENSHIP AND PUBLIC SERVICE EX-STUDENTS ASSOCIATION OFFICERS President .................. W. B . Rushing '32 Vice-President ............... Olaf Loda! '32 2nd Vice-Pres. ............... Bob Dowell '40 Director ........................ 0 . R. McElya '34 Director .................. Hart Shoemaker '41 Director ....- ..... Forrest Weimhold '36 Immediate Past. Pres. Ed McCullough '32 Vol. 1, No. 7 December, 1950 Rep. to Athletic Council George Langford '32 Exec. Secretary.. .... D. M. McElroy '35 CONTENTS * * * FEATURES LOYALTY FUND Homecoming, 1950 ----------------------------·-----------· --------------------------------------- 2 A recap of the big day's events TRUSTEES Time for Reminiscin' -----------· -------------------------------------------------------------------- 4 Class reunions-a howling success Olaf Lodal E. A. McCullou-gh Build ing Program Dedicated _____________________________ ____ ____ ___________ ________ ___________ 6 Fred Rollins W. B. -

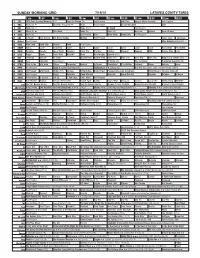

Sunday Morning Grid 7/19/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 7/19/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Morning (N) Å Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Golf Res. Gospel Music Presents Paid Program 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Paid Program Beach Volleyball Golf 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Explore Open Champ. 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Hour Mike Webb Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program I Love Lucy I Love Lucy 13 MyNet Paid Program Miss Nobody (2010) (R) 18 KSCI Man Land Rock Star Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Cosas Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local RescueBot RescueBot 24 KVCR Painting Dowdle Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexican Cooking BBQ Simply Ming Lidia 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Insight Special (TVG) 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY) Doki (TVY) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly Rudy ››› (1993) (PG) 34 KMEX Paid Conexión Paid Program Al Punto (N) Tras la Verdad República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Hour of In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program Zoom › (2006) Tim Allen. (PG) Chimpanzee ›› (2012) (G) Ben Hur Un príncipe judío enfrenta traición. -

Baby Daddy: a Family Business

SEPTEMBER 2013 Baby Daddy: A Family Business . (ABC FAMILY/ANDREW ECCLES) ED V RESER RIGHTS LL . A NC , I NTERPRISES E ISNEY © 2012 D ABC Family’s Baby Daddy stars Chelsea Kane as Riley, Derek Theler as Danny, Jean-Luc Bilodeau as Ben, twins Ali and Susanne Hartman as Emma, Melissa Peterman as Bonnie and Tahj Mowry as Tucker. By Marissa Berlin 5:00 PM — It’s a Friday evening, and a line What Baby Daddy shares with such revered clan means they also have a lot of love for of smiling fans shuffles in to Stage 20. Most comedies as Seinfeld, Will & Grace, and The the Baby Daddy Family as a whole. think they’re here to simply see a show, but Mary Tyler Moore Show goes beyond its multi- those colored wristbands they’re wearing camera format (or where it’s shot!). In its Created by Executive Producer Dan have just made them an integral part of the respective decade, each of these shows Berendsen (The Nine Lives of Chloe King, larger Baby Daddy “Family” – a dedicated became a hit because it reflected America Sabrina the Teenage Witch) and directed by group of people who all contribute to the through the antics of its on-screen family. Michael Lembeck (Friends, Mad About You) success of the show. And that’s not all: in Whether it was a group of friends, a herd of Baby Daddy is the story of Ben Wheeler (Jean- laughing along with a live taping here at workplace colleagues, or an actual family… Luc Bilodeau) becoming a surprise father CBS Radford, this audience will also join the on-screen cast was only a part of that to a baby girl left on his doorstep by an ex- a continuum of sitcom families among the larger Family. -

TV Land's Newest Sitcom, "The Exes," (Working Title) Begins Production on First Season

TV Land's Newest Sitcom, "The Exes," (Working Title) Begins Production on First Season Series By Mark Reisman Stars Television Comedy Vets Donald Faison, Wayne Knight, David Alan Basche, Kelly Stables and Kristen Johnston Show Premieres Wednesday, November 30 At 10:30 PM ET/PT After Season Three Premiere Of "Hot in Cleveland" LOS ANGELES, July 21, 2011 /PRNewswire via COMTEX/ -- TV Land announced today that production starts this week on the network's new original sitcom, "The Exes" (working title). The series, which is written by Mark Reisman ("Frasier"), will debut on TV Land on Wednesday, November 30 at 10:30 pm ET/PT immediately following the season three premiere of "Hot in Cleveland." The program stars critically-acclaimed actors Donald Faison ("Scrubs"), Wayne Knight ("Seinfeld," "Hot in Cleveland"), David Alan Basche ("The Starter Wife"), Kelly Stables ("Two and a Half Men") and Emmy® Award-winner Kristen Johnston ("3rd Rock From The Sun"). In TV Land's latest sitcom, divorce attorney Holly (Johnston) introduces her newly-single client Stuart (Basche) to his new roommates - ladies' man Phil (Faison) and homebody Haskell (Knight), who share an apartment which Holly owns. Things start off a little shaky when the two bachelors have reservations about living with clingy Stuart, but Holly is right across the hall to help them avoid any catastrophes. To top it all off, Holly's assistant, Eden (Stables), doesn't exactly let her professionalism get in the way of prying into her boss's personal life. "We are so excited to start production on this sitcom," said Larry W. -

New Series Monday 20Th April 9Pm

NEW SERIES MONDAY 20TH APRIL 9PM Beyond explanation… beyond Jo Evans (Allison Tolman), a whip-smart police What happens when a regular family is gripped understanding… lies the truth. This chief, plunges her family into a deepening by unimaginable circumstances? mystery when she discovers a young girl “Emergence” stars Allison Tolman as Jo Evans, character-driven genre thriller (Alexa Swinton) the night of an inexplicable Alexa Swinton as Piper, Owain Yeoman as follows a police chief who takes in a plane crash in the quiet north eastern town Benny Gallagher, Ashley Aufderheide as Mia young child she finds near the site and decides to protect her. Who is this child? Evans, Robert Bailey Jr. as Officer Chris Minetto, of a mysterious accident who has Where did she come from and what does she Zabryna Guevara as Abby Frasier with Donald no memory of what has happened. know? Benny Gallagher (Owain Yeoman), an Faison as Alex Evans and Clancy Brown as investigative reporter, intrudes into Jo’s inquiry Ed Sawyer. The investigation draws her into with his own take on the shadowy evidence. a conspiracy larger than she ever Written and executive produced by Michele imagined, and the child’s identity is Jo must balance her growing, protective Fazekas & Tara Butters (“Kevin (Probably) at the centre of it all. relationship with Piper with her love and Saves the World,” “Marvel’s Agent Carter,” concern for her own family: her daughter, Mia “Resurrection,” “Reaper”), Paul McGuigan directs (Ashley Aufderheide); her father, Ed (Clancy the pilot and is an executive producer. Brown); and her ex-husband, Alex (Donald Faison).