Before the FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ABC ME Program Guide: Week 28 Index

1 | P a g e ABC ME Program Guide: Week 28 Index Index Program Guide .............................................................................................................................................................. 3 Sunday, 4 July 2021 ............................................................................................................................................... 3 Monday, 5 July 2021 ............................................................................................................................................. 7 Tuesday, 6 July 2021 ........................................................................................................................................... 11 Wednesday, 7 July 2021 ...................................................................................................................................... 15 Thursday, 8 July 2021 .......................................................................................................................................... 19 Friday, 9 July 2021 ............................................................................................................................................... 23 Saturday, 10 July 2021 ........................................................................................................................................ 27 NOTE: Program times may differ in some states if viewing on VAST or Foxtel. More information can be found at ABC Help. 2 | P a g e ABC ME Program Guide: Week 28 Sunday, 4 July 2021 Program -

Organized Crime and Terrorist Activity in Mexico, 1999-2002

ORGANIZED CRIME AND TERRORIST ACTIVITY IN MEXICO, 1999-2002 A Report Prepared by the Federal Research Division, Library of Congress under an Interagency Agreement with the United States Government February 2003 Researcher: Ramón J. Miró Project Manager: Glenn E. Curtis Federal Research Division Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 20540−4840 Tel: 202−707−3900 Fax: 202−707−3920 E-Mail: [email protected] Homepage: http://loc.gov/rr/frd/ Library of Congress – Federal Research Division Criminal and Terrorist Activity in Mexico PREFACE This study is based on open source research into the scope of organized crime and terrorist activity in the Republic of Mexico during the period 1999 to 2002, and the extent of cooperation and possible overlap between criminal and terrorist activity in that country. The analyst examined those organized crime syndicates that direct their criminal activities at the United States, namely Mexican narcotics trafficking and human smuggling networks, as well as a range of smaller organizations that specialize in trans-border crime. The presence in Mexico of transnational criminal organizations, such as Russian and Asian organized crime, was also examined. In order to assess the extent of terrorist activity in Mexico, several of the country’s domestic guerrilla groups, as well as foreign terrorist organizations believed to have a presence in Mexico, are described. The report extensively cites from Spanish-language print media sources that contain coverage of criminal and terrorist organizations and their activities in Mexico. -

February 26, 2021 Amazon Warehouse Workers In

February 26, 2021 Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer, Alabama are voting to form a union with the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU). We are the writers of feature films and television series. All of our work is done under union contracts whether it appears on Amazon Prime, a different streaming service, or a television network. Unions protect workers with essential rights and benefits. Most importantly, a union gives employees a seat at the table to negotiate fair pay, scheduling and more workplace policies. Deadline Amazon accepts unions for entertainment workers, and we believe warehouse workers deserve the same respect in the workplace. We strongly urge all Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer to VOTE UNION YES. In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (DARE ME) Chris Abbott (LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE; CAGNEY AND LACEY; MAGNUM, PI; HIGH SIERRA SEARCH AND RESCUE; DR. QUINN, MEDICINE WOMAN; LEGACY; DIAGNOSIS, MURDER; BOLD AND THE BEAUTIFUL; YOUNG AND THE RESTLESS) Melanie Abdoun (BLACK MOVIE AWARDS; BET ABFF HONORS) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS; CLOSE ENOUGH; A FUTILE AND STUPID GESTURE; CHILDRENS HOSPITAL; PENGUINS OF MADAGASCAR; LEVERAGE) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; GROWING PAINS; THE HOGAN FAMILY; THE PARKERS) David Abramowitz (HIGHLANDER; MACGYVER; CAGNEY AND LACEY; BUCK JAMES; JAKE AND THE FAT MAN; SPENSER FOR HIRE) Gayle Abrams (FRASIER; GILMORE GIRLS) 1 of 72 Jessica Abrams (WATCH OVER ME; PROFILER; KNOCKING ON DOORS) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEPPER) Nick Adams (NEW GIRL; BOJACK HORSEMAN; -

Violence Within: Understanding the Use of Violent Practices Among Mexican Drug Traffickers

Violence within: Understanding the Use of Violent Practices Among Mexican Drug Traffickers By Dr. Karina García JUSTICE IN MEXICO WORKING PAPER SERIES Volume 16, Number 2 November 2019 About Justice in Mexico: Started in 2001, Justice in Mexico (www.justiceinmexico.org) is a program dedicated to promoting analysis, informed public discourse, and policy decisions; and government, academic, and civic cooperation to improve public security, rule of law, and human rights in Mexico. Justice in Mexico advances its mission through cutting-edge, policy-focused research; public education and outreach; and direct engagement with policy makers, experts, and stakeholders. The program is presently based at the Department of Political Science and International Relations at the University of San Diego (USD), and involves university faculty, students, and volunteers from the United States and Mexico. From 2005 to 2013, the program was based at USD’s Trans-Border Institute at the Joan B. Kroc School of Peace Studies, and from 2001 to 2005 it was based at the Center for U.S.-Mexican Studies at the University of California-San Diego. About this Publication: This paper forms part of the Justice in Mexico working paper series, which includes recent works in progress on topics related to crime and security, rule of law, and human rights in Mexico. All working papers can be found on the Justice in Mexico website: www.justiceinmexico.org. The research for this paper involved in depth interviews with over thirty participants in violent aspects of the Mexican drug trade, and sheds light on the nature and purposes of violent activities conducted by Mexican organized crime groups. -

Clones Stick Together

TVhome The Daily Home April 12 - 18, 2015 Clones Stick Together Sarah (Tatiana Maslany) is on a mission to find the 000208858R1 truth about the clones on season three of “Orphan Black,” premiering Saturday at 8 p.m. on BBC America. The Future of Banking? We’ve Got A 167 Year Head Start. You can now deposit checks directly from your smartphone by using FNB’s Mobile App for iPhones and Android devices. No more hurrying to the bank; handle your deposits from virtually anywhere with the Mobile Remote Deposit option available in our Mobile App today. (256) 362-2334 | www.fnbtalladega.com Some products or services have a fee or require enrollment and approval. Some restrictions may apply. Please visit your nearest branch for details. 000209980r1 2 THE DAILY HOME / TV HOME Sun., April 12, 2015 — Sat., April 18, 2015 DISH AT&T DIRECTV CABLE CHARTER CHARTER PELL CITY PELL ANNISTON CABLE ONE CABLE TALLADEGA SYLACAUGA BIRMINGHAM BIRMINGHAM BIRMINGHAM CONVERSION CABLE COOSA SPORTS WBRC 6 6 7 7 6 6 6 6 AUTO RACING Friday WBIQ 10 4 10 10 10 10 6 p.m. FS1 St. John’s Red Storm at Drag Racing WCIQ 7 10 4 Creighton Blue Jays (Live) WVTM 13 13 5 5 13 13 13 13 Sunday Saturday WTTO 21 8 9 9 8 21 21 21 7 p.m. ESPN2 Summitracing.com 12 p.m. ESPN2 Vanderbilt Com- WUOA 23 14 6 6 23 23 23 NHRA Nationals from The Strip at modores at South Carolina WEAC 24 24 Las Vegas Motor Speedway in Las Gamecocks (Live) WJSU 40 4 4 40 Vegas (Taped) 2 p.m. -

Touchstones of Popular Culture Among Contemporary College Students in the United States

Minnesota State University Moorhead RED: a Repository of Digital Collections Dissertations, Theses, and Projects Graduate Studies Spring 5-17-2019 Touchstones of Popular Culture Among Contemporary College Students in the United States Margaret Thoemke [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://red.mnstate.edu/thesis Part of the Higher Education and Teaching Commons Recommended Citation Thoemke, Margaret, "Touchstones of Popular Culture Among Contemporary College Students in the United States" (2019). Dissertations, Theses, and Projects. 167. https://red.mnstate.edu/thesis/167 This Thesis (699 registration) is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at RED: a Repository of Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Projects by an authorized administrator of RED: a Repository of Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Touchstones of Popular Culture Among Contemporary College Students in the United States A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of Minnesota State University Moorhead By Margaret Elizabeth Thoemke In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Teaching English as a Second Language May 2019 Moorhead, Minnesota iii Copyright 2019 Margaret Elizabeth Thoemke iv Dedication I would like to dedicate this thesis to my three most favorite people in the world. To my mother, Heather Flaherty, for always supporting me and guiding me to where I am today. To my husband, Jake Thoemke, for pushing me to be the best I can be and reminding me that I’m okay. Lastly, to my son, Liam, who is my biggest fan and my reason to be the best person I can be. -

OCTOBER 2015 David Haring, Editor & Photographer • Design by Hilliker Designs

DLC HOSTS Colleagues FROM Madagascar DUKE ANDREA KatZ, Curator, LIVING ANIMAL COLLECTIONS LEMUR CENTER In May and June, the Duke Lemur Center discuss ways that we can collaborate further to achieve com- (DLC) had the pleasure and great honor to mon conservation goals. The discussions were expanded host two Malagasy colleagues: Eric Robso- when Eric and Bernard attended the Prosimian Taxon Advi- manitrandrasana of the Ministry of the Envi- sory Group’s annual meeting with several members of the ronment, Ecology, Oceans and Forests and DLC technician staff. As a result, in July an official “Accord Bernard Iambana, Manager of Zoo Ivoloina/ of Collaboration” between the Government of Madagascar, Conservation Manager, Madagascar Fauna and American (AZA) and European (EAZA) groups was final- Flora Group. We would like to express our ized- to promote global ex situ and in situ conservation of most heartfelt thanks to the Kris and Peter the critically endangered blue-eyed black lemur (Eulemur Norvig Family Fund for supporting this inter- flavifrons). Named on the 2012, 2013 and 2014 IUCN List of national exchange. the 25 Most Endangered Primates, this species desperately The purpose of their visit was to learn first- needs cooperative global management to survive. And as hand about the DLC’s best practices for lemur the only North American institution successfully breeding care and management. In Madagascar, Eric is blue-eyed black lemurs, the DLC stands ready to do all we the coordinator of a new government initiative possibly can. to improve husbandry standards and breeding management for hundreds of lemurs that are kept in Madagascar’s zoos and private wildlife parks. -

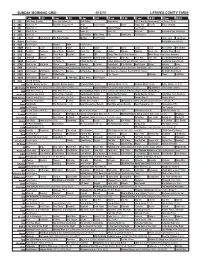

Sunday Morning Grid 4/12/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 4/12/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Bull Riding Remembers 2015 Masters Tournament Final Round. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Paid Program Luna! Poppy Cat Tree Fu Figure Skating 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Explore Incredible Dog Challenge 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program I Love Lucy I Love Lucy 13 MyNet Paid Program Red Lights ›› (2012) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Cosas Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local RescueBot RescueBot 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Cooking Chefs Life Simply Ming Lidia 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News TBA Things That Aren’t Here Anymore More Things Aren’t Here Anymore 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY) Doki Ad Dive, Olly Dive, Olly E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División: Toluca vs Atlas República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Best Praise Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program Hocus Pocus ›› (1993) Bette Midler. -

ANNUAL REPORT 2015 16 A70 TV Acad Ad.Qxp Layout 1 7/8/16 11:43 AM Page 1

ANNUAL REPORT 2015 16_A70_TV_Acad_Ad.qxp_Layout 1 7/8/16 11:43 AM Page 1 PROUD MEMBER OF »CBS THE TELEVISION ACADEMY 2 ©2016 CBS Broadcasting Inc. MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIRMAN AND CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER AS THE QUANTITY AND QUALITY OF CONTENT HAVE INCREASED in what is widely regarded as television’s second Golden Age, so have employment opportunities for the talented men and women who create that programming. And as our industry, and the content we produce, have become more relevant, so has the relevance of the Television Academy increased as an essential resource for television professionals. In 2015, this was reflected in the steady rise in our membership — surpassing 20,000 for the first time in our history — as well as the expanding slate of Academy-sponsored activities and the heightened attention paid to such high-profile events as the Television Academy Honors and, of course, the Creative Arts Awards and the Emmy Awards. Navigating an industry in the midst of such profound change is both exciting and, at times, a bit daunting. Reimagined models of production and distribution — along with technological innovations and the emergence of new over-the-top platforms — have led to a seemingly endless surge of creativity, and an array of viewing options. As the leading membership organization for television professionals and home to the industry’s most prestigious award, the Academy is committed to remaining at the vanguard of all aspects of television. Toward that end, we are always evaluating our own practices in order to stay ahead of industry changes, and we are proud to guide the conversation for television’s future generations. -

Nickelodeon Previews New Content Pipeline for 2014-2015 Season at Annual Upfront Presentation

Nickelodeon Previews New Content Pipeline for 2014-2015 Season at Annual Upfront Presentation Nick to Add 10 New Series to Schedule, with Content Spanning Every Genre, Every Platform Network Unveils Plans for Brand-New, Live Tent-Pole Event, Kids' Choice Sports 2014; Host/Executive Producer Michael Strahan Details Show Slated for 3Q 2014 Upfront Presentation Capped by Special Musical Performance from Five-Time Grammy Nominee Sara Bareilles NEW YORK--(BUSINESS WIRE)-- Nickelodeon held its annual upfront presentation today at Jazz at Lincoln Center in New York City, where Nickelodeon Group President Cyma Zarghami detailed the network's biggest content pipeline ever: 10 new series across every genre, and for every platform—all tailor-made for the tastes of today's post-millennial generation of kids. Zarghami also announced plans for the forthcoming Nick Jr. App, featuring TV Everywhere capability, and the brand-new, live tent-pole event, Kids' Choice Sports—the first-ever expansion of the highly successful Kids' Choice Awards franchise. Nickelodeon's presentation was also punctuated by remarks from Viacom Chairman Philippe Dauman; an appearance by Kids' Choice Sports 2014 host and executive producer Michael Strahan; and a closing musical performance from five-time Grammy nominee Sara Bareilles. "Our mission has been to create and deliver funny content that will resonate with today's kids, and we are well-positioned to do that through our schedule of fresh hits, a deep pipeline of new series, tent-pole events, ratings momentum and innovation on all platforms," said Zarghami. "Nickelodeon is a magnet for creative people and projects, and we're incredibly excited about the new pool of talent we're bringing to our audience in front of and behind the camera." Nickelodeon has posted 13 straight months of year-over-year growth and reclaimed the top spot with kids in 4Q13. -

Weekend Glance

Friday, Dec. 1, 2017 Vol. 11 No. 43 12040 Foster Road, Norwalk, CA 90650 Norwalk Norwalk City Council votes restaurant to give themselves grades Donut King 12000 Rosecrans Ave. NOVEMBER 30 12 more months in office Date Inspected: 11/17/17 FridayWeekend74˚ Neighborhood Watch meeting Grade: B CITY COUNCIL: Council members at a DATE: Thursday, Nov. 30 Glance choose to extend elections one year Buy Low Market TIME: 6:30 pm under legislation signed by Gov. Jerry Saturday 75˚⁰ LOCATION: Paddison Elementary 10951 Rosecrans Ave. 68 Brown. Date Inspected: 11/13/17 Friday DECEMBER 2 Grade: B By Raul Samaniego SnowFest and Christmas Tree Contributor Wienerschnitzel Sunday 71˚70⁰ Lighting 11660 Imperial Hwy. Saturday DATE: Saturday, Dec. 2 NORWALK – The Norwalk City Date Inspected: 11/15/17 TIME: 12-8 pm Council voted 5-0 on November Grade: A 21, to approve Ordinance 17-1698 LOCATION: City Hall lawn which called for the changing of Waba Grill Holiday Sonata Election Dates to comply with 11005 Firestone Blvd. California Senate Bill 415. DATE: Saturday, Dec. 2 Date Inspected: 11/16/17 TIME: 4-9 pm For Norwalk residents, it means Grade: A that with the approval of the Norwalk’s next election will be in 2020. Photo courtesy city of LOCATION: Uptown Whittier ordinance, “all five council members Norwalk Ana’s Bionicos have added another 12 months to 11005 Firestone Blvd. DECEMBER 5 their terms,” according to City Clerk numbered years to even, it could California’s history. Date Inspected: 11/16/17 Theresa Devoy increase the voter turnout for those City Council meeting This transition was mandated Grade: A elections. -

Nick at Nite Debuts Instant Mom, Original Family Comedy Starring Tia Mowry-Hardrict, Sunday, Sept

Nick at Nite Debuts Instant Mom, Original Family Comedy Starring Tia Mowry-Hardrict, Sunday, Sept. 29, At 8:30 P.M. (ET/PT) Brand-New Nick at Nite Series Co-Stars Michael Boatman and Sheryl Lee Ralphand also Airs at 10 p.m. on NickMom SANTA MONICA, Calif., Sept. 5, 2013 /PRNewswire/ -- Nick at Nite will premiere Instant Mom, the brand-new, live-action family sitcom starring and produced by Tia Mowry-Hardrict (star of STYLE Network's hit series Tia & Tamera), on Sunday, Sept. 29, at 8:30 p.m. (all times ET/PT). The multi-camera, scripted half-hour series features Mowry-Hardrict as Stephanie, a party girl who trades in Cosmos for carpools when she marries Charlie (Michael Boatman, Spin City), who already has three kids. Airing regularly on Nick at Nite Sundays at 8:30 p.m. (ET/PT), the series also will air on the adult-targeted NickMom comedy block on the Nick Jr. channel at 10p.m. (Photo: http://photos.prnewswire.com/prnh/20130905/NY74999 ) "In Instant Mom, Tia vividly captures what it's like to jump into motherhood with nearly zero experience, and her stepchildren take a front row in her labors," said Russell Hicks, Nickelodeon's President of Content Development and Production. "Their comedic and authentic approach to their disparities as a new family will make audiences fall in love with the growing and heartfelt appreciation for each other and for the all-embracing blended family they are now a part of." Instant Mom follows Stephanie as she struggles to maintain some sense of her fun-loving, slightly irresponsible life while managing being a full-time stepmom.