Download Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Christie's Hong Kong Presents Important Chinese

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE October 23, 2008 Contact: Kate Swan Malin +852 2978 9966 [email protected] Yvonne So +852 2978 9919 [email protected] CHRISTIE’S HONG KONG PRESENTS IMPORTANT CHINESE CERAMICS & WORKS OF ART WITH FIVE DEDICATED SALES Hong Kong – Christie’s Hong Kong fall sales of Important Ceramics and Works of Art will take place on December 3 at the Hong Kong Convention & Exhibition Centre. With several important collections and single-owner sales presented during this day-long series, collectors will be treated to a wide range of unique objects across multiple categories. These five sales offer over 300 works of ceramics, lacquer, bamboo, furniture, textiles, and jade carvings with a combined estimate in excess of HK$300 million (US$38 million). This series of auctions includes a number of important single-owner sales and collections. Among the most anticipated sales this season is that of the unrivalled group of lacquers from the famed Lee Family Collection. A fine selection of Chinese bamboo carvings from the personal collection of Mr. and Mrs. Gerard Hawthorn will also be offered in a single-owner sale, presenting a comprehensive range of 16th to 18th century examples of this scholarly art form that they have passionately collected for over 45 years. Christie’s honours the centenary of the passing of the Dowager Empress Cixi with a special sale that celebrates the elegance of the late Qing dynasty. And offered on behalf of the Ping Y. Tai Foundation, with proceeds benefiting their numerous charitable causes, is a tremendous Imperial Famille Rose ‘Butterfly’ Vase, an absolute masterpiece of Qing Imperial porcelain. -

Ceramic's Influence on Chinese Bronze Development

Ceramic’s Influence on Chinese Bronze Development Behzad Bavarian and Lisa Reiner Dept. of MSEM College of Engineering and Computer Science September 2007 Photos on cover page Jue from late Shang period decorated with Painted clay gang with bird, fish and axe whorl and thunder patterns and taotie design from the Neolithic Yangshao creatures, H: 20.3 cm [34]. culture, H: 47 cm [14]. Flat-based jue from early Shang culture Pou vessel from late Shang period decorated decorated with taotie beasts. This vessel with taotie creatures and thunder patterns, H: is characteristic of the Erligang period, 24.5 cm [34]. H: 14 cm [34]. ii Table of Contents Abstract Approximate timeline 1 Introduction 2 Map of Chinese Provinces 3 Neolithic culture 4 Bronze Development 10 Clay Mold Production at Houma Foundry 15 Coins 16 Mining and Smelting at Tonglushan 18 China’s First Emperor 19 Conclusion 21 References 22 iii The transition from the Neolithic pottery making to the emergence of metalworking around 2000 BC held significant importance for the Chinese metal workers. Chinese techniques sharply contrasted with the Middle Eastern and European bronze development that relied on annealing, cold working and hammering. The bronze alloys were difficult to shape by hammering due to the alloy combination of the natural ores found in China. Furthermore, China had an abundance of clay and loess materials and the Chinese had spent the Neolithic period working with and mastering clay, to the point that it has been said that bronze casting was made possible only because the bronze makers had access to superior ceramic technology. -

Lunar Mansions in the Early Han (C

Cosmologies of Change The Inscapes of the Classic of Change Stephen Karcher Ph.D. 1 2 Sections Cosmologies of Change Yellow Dragon Palace Azure Dragon Palace Vermillion Bird Palace Black Turtle Palace The Matrix of Change 3 Cosmologies of Change The tradition or Way of the Classic of Change is like a great stream of symbols flowing back and forth through the present moment to connect the wisdom of ancient times with whatever the future may be. It is a language that everything speaks; through it everything is always talking to everything else. Things are always vanishing and coming into being, a continual process of creation that becomes knowable or readable at the intersection points embodied in the symbols of this language. These symbols or images of Change open a sacred cosmos that has acted as a place of close encounter with the spirit world for countless generations. Without this sort of contact our world shrinks and fades away, leaving us in a deaf and dumb wasteland, forever outside of things. 31:32 Conjoining and Persevering displays the process through which spirit enters and influences the human world, offering omens that, when given an enduring form, help the heart endure on the voyage of life. This cosmos has the shape of the Numinous Turtle, swimming in the endless seas of the Way or Dao. Heaven is above, Earth and the Ghost River are below, the Sun Tree lies to the East, the Moon Tree is in the far West. The space between, spread to the Four Directions, is the world we live in, full of shrines and temples where we talk with the ghosts and spirits, hidden winds, elemental powers and dream animals. -

Ancient Chinese Constellations Junjun Xu Beijing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics Room 424, Apartment 20, No

The Role of Astronomy in Society and Culture Proceedings IAU Symposium No. 260, 2009 c International Astronomical Union 2011 D. Valls-Gabaud & A. Boksenberg, eds. doi:10.1017/S174392131100319X Ancient Chinese constellations Junjun Xu Beijing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics Room 424, Apartment 20, No. 37 Xueyuan Street, Beijing, China email: [email protected] Abstract. China, a country with a long history and a specific culture, has also a long and specific astronomy. Ancient Chinese astronomers observed the stars, named and distributed them into constellations in a very specific way, which is quite different from the current one. Around the Zodiac, stars are divided into four big regions corresponding with the four orientations, and each is related to a totem, either the Azure Dragon, the Vermilion Bird, the White Tiger or the Murky Warrior. We present a general pattern of the ancient Chinese constellations, including the four totems, their stars and their names. Keywords. China, constellations, mansions 1. Introduction Three enclosures, four symbols and twenty-eight mansions characterise the ancient Chinese constellations. This division of the starry sky began to appear in China before the Zhou and Qin dynasties. The three enclosures refer to three areas around the North celestial pole: the Purple Forbidden enclosure, the Supreme Palace enclosure and the Heavenly Market enclosure. The four symbols are distributed near the ecliptic Zodiac and the lunar orbit and are represented by four totems: the Azure Dragon of the East, the Vermillion Bird of the South, the White Tiger of the West and the Black Tortoise of the North. Every symbol was divided into seven sections which were know as mansions. -

The Symbol of the Dragon and the Tiger in Chinese and Japanese Art

THE RULERS OF SKY AND EARTH THE SYMBOL OF THE DRAGON AND THE TIGER IN CHINESE AND JAPANESE ART Grade Level This lesson is written for grades 9-12; it can be used in a World History or an Art class. Purpose To look at how symbols of power, the dragon and the tiger, are portrayed in the art of China and Japan; students will then compare and contrast this with the Western conception and portrayal of the dragon. Concepts In the Western world, dragons are portrayed as evil, fire-breathing creatures that must be subdued and killed by heroes. The Western dragon is seen as essentially negative, a symbol of evil and a sign of the devil. In Asia, the dragon is a positive force, a symbol of peace and harmony. Chinese and Japanese dragons are considered to be benevolent and auspicious. They breathe water rather than fire and have the power to bring rain, an important attribute in an agricultural society. The Chinese dragon is a supernatural, mythical creature that inhabits the sky and the waters and is connected with clouds, rains, and fertility on one hand and the emperor and his venerated ancestors on the other. For the last 4,000 years, the dragon has intertwined itself into all phases of China's social and political life as well as every form of art and literature. The dragon is the most important symbol of power, and the symbol of the emperor; no other animal has occupied such an important place in the thought and art of the Chinese people. -

The Great NPC Revolt

½ Prince Volume 6: The Great NPC Revolt http://www.princerevolution.org ½ Prince Volume 5: A Prince No More http://www.princerevolution.org SYNOPSIS: The conference of the conquerors of the five continents has begun – come, come, the discussion table has been readied. Infinite City has been decorated for the occasion, and the lord of Infinite City must also be dressed grandly for the occasion. That way, this conference will be formal and solemn, right? “The Dictator of Life” – who is that? I’ve never heard of him before! Oh, so he… 1. Is the ultimate boss of Second Life, 2. Is an unmatched AI, in control of the whole of Second Life, so you could call him the God of Second Life, 3. Has developed free will, and… 4. Intends to rebel against humans by kicking out all the players from Second Life Shit, if we can’t kill the Dictator of Life within twenty-one days, Second Life will be destroyed by the company and disappear forever…! Will Kenshin and Sunshine also disappear together with the game? Within twenty-one days, the final plan to save Second Life by “launching our counterattack on the Northern Continent and killing the Dictator of Life” must be carried out! ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Yu Wo: Who am I? Sometimes I am like a warrior, wielding a sword on the battlefield with limitless passion and energy. At other times, I resemble a mage, with a mind devoted to research, completely absorbed in the things I like. Or I might be like a thief, leading a free and easy life, letting fate lead me to distant and unfamiliar lands. -

Tier 1 Manufacturing Sites

TIER 1 MANUFACTURING SITES - Produced January 2021 SUPPLIER NAME MANUFACTURING SITE NAME ADDRESS PRODUCT TYPE No of EMPLOYEES Albania Calzaturificio Maritan Spa George & Alex 4 Street Of Shijak Durres Apparel 100 - 500 Calzificio Eire Srl Italstyle Shpk Kombinati Tekstileve 5000 Berat Apparel 100 - 500 Extreme Sa Extreme Korca Bul 6 Deshmoret L7Nr 1 Korce Apparel 100 - 500 Bangladesh Acs Textiles (Bangladesh) Ltd Acs Textiles & Towel (Bangladesh) Tetlabo Ward 3 Parabo Narayangonj Rupgonj 1460 Home 1000 - PLUS Akh Eco Apparels Ltd Akh Eco Apparels Ltd 495 Balitha Shah Belishwer Dhamrai Dhaka 1800 Apparel 1000 - PLUS Albion Apparel Group Ltd Thianis Apparels Ltd Unit Fs Fb3 Road No2 Cepz Chittagong Apparel 1000 - PLUS Asmara International Ltd Artistic Design Ltd 232 233 Narasinghpur Savar Dhaka Ashulia Apparel 1000 - PLUS Asmara International Ltd Hameem - Creative Wash (Laundry) Nishat Nagar Tongi Gazipur Apparel 1000 - PLUS Aykroyd & Sons Ltd Taqwa Fabrics Ltd Kewa Boherarchala Gila Beradeed Sreepur Gazipur Apparel 500 - 1000 Bespoke By Ges Unip Lda Panasia Clothing Ltd Aziz Chowdhury Complex 2 Vogra Joydebpur Gazipur Apparel 1000 - PLUS Bm Fashions (Uk) Ltd Amantex Limited Boiragirchala Sreepur Gazipur Apparel 1000 - PLUS Bm Fashions (Uk) Ltd Asrotex Ltd Betjuri Naun Bazar Sreepur Gazipur Apparel 500 - 1000 Bm Fashions (Uk) Ltd Metro Knitting & Dyeing Mills Ltd (Factory-02) Charabag Ashulia Savar Dhaka Apparel 1000 - PLUS Bm Fashions (Uk) Ltd Tanzila Textile Ltd Baroipara Ashulia Savar Dhaka Apparel 1000 - PLUS Bm Fashions (Uk) Ltd Taqwa -

Daily Life for the Common People of China, 1850 to 1950

Daily Life for the Common People of China, 1850 to 1950 Ronald Suleski - 978-90-04-36103-4 Downloaded from Brill.com04/05/2019 09:12:12AM via free access China Studies published for the institute for chinese studies, university of oxford Edited by Micah Muscolino (University of Oxford) volume 39 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/chs Ronald Suleski - 978-90-04-36103-4 Downloaded from Brill.com04/05/2019 09:12:12AM via free access Ronald Suleski - 978-90-04-36103-4 Downloaded from Brill.com04/05/2019 09:12:12AM via free access Ronald Suleski - 978-90-04-36103-4 Downloaded from Brill.com04/05/2019 09:12:12AM via free access Daily Life for the Common People of China, 1850 to 1950 Understanding Chaoben Culture By Ronald Suleski leiden | boston Ronald Suleski - 978-90-04-36103-4 Downloaded from Brill.com04/05/2019 09:12:12AM via free access This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the prevailing cc-by-nc License at the time of publication, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. More information about the initiative can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org. Cover Image: Chaoben Covers. Photo by author. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Suleski, Ronald Stanley, author. Title: Daily life for the common people of China, 1850 to 1950 : understanding Chaoben culture / By Ronald Suleski. -

Records of the Transmission of the Lamp (Jingde Chuadeng

The Hokun Trust is pleased to support the fifth volume of a complete translation of this classic of Chan (Zen) Buddhism by Randolph S. Whitfield. The Records of the Transmission of the Lamp is a religious classic of the first importance for the practice and study of Zen which it is hoped will appeal both to students of Buddhism and to a wider public interested in religion as a whole. Contents Foreword by Albert Welter Preface Acknowledgements Introduction Appendix to the Introduction Abbreviations Book Eighteen Book Nineteen Book Twenty Book Twenty-one Finding List Bibliography Index Foreword The translation of the Jingde chuandeng lu (Jingde era Record of the Transmission of the Lamp) is a major accomplishment. Many have reveled in the wonders of this text. It has inspired countless numbers of East Asians, especially in China, Japan and Korea, where Chan inspired traditions – Chan, Zen, and Son – have taken root and flourished for many centuries. Indeed, the influence has been so profound and pervasive it is hard to imagine Japanese and Korean cultures without it. In the twentieth century, Western audiences also became enthralled with stories of illustrious Zen masters, many of which are rooted in the Jingde chuandeng lu. I remember meeting Alan Ginsburg, intrepid Beat poet and inveterate Buddhist aspirant, in Shanghai in 1985. He had been invited as part of a literary cultural exchange between China and the U. S., to perform a series of lectures for students at Fudan University, where I was a visiting student. Eager to meet people who he could discuss Chinese Buddhism with, I found myself ushered into his company to converse on the subject. -

Fenghuang and Phoenix: Translation of Culture

International Journal of Languages, Literature and Linguistics, Vol. 6, No. 3, September 2020 Fenghuang and Phoenix: Translation of Culture Lyujie Zhu Confucius‟ time, fenghuang was mainly used to describe Abstract—Fenghuang and phoenix from ancient myths are virtuous man, such as shi and king, and it was in Han dynasty both culture-loaded words that have unique features and that fenghuang‟s gender was gradually distinguished [18], as comprehensive historical developing routes. This paper focuses the male feng with the female huang respectively, in on their translations to find out the reflected cultural issues and symbolizing everlasting love that representing the yin-yang power influences under the ideas of cultural identity and language power. Classic literatures like The Analects and The balance. After Ming-Qing period, fenghuang was major Tempest in bilingual versions are compared in terms of the symbolization for female that such transformation is translation for both animals, as well as by searching the unavoidably related to the monarchal power of Chinese different social backgrounds and timelines of those literatures. empresses in indicating themselves by using The mixed usage of phoenix and fenghuang in both Chinese fenghuang-elements [16]. (East) and English (West) culture makes confusions but also As for phoenix in the West, it has the totally different enriches both languages and cultures. origins and characteristics. Phoenix dies in its nest, and then Index Terms—Fenghuang, phoenix, translation, language, is reborn from its own burned ashes, with a duration of about cultural identity. 500 years [19]. Phoenix is said to be originated from Egyptian solar myths of the sacred bird, benu, through association with the self-renewing solar deity, Osiris [20]. -

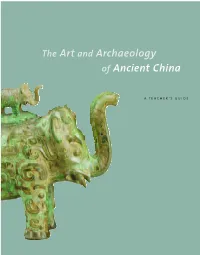

T H E a Rt a N D a Rc H a E O L O Gy O F a N C I E Nt C H I

china cover_correct2pgs 7/23/04 2:15 PM Page 1 T h e A r t a n d A rc h a e o l o g y o f A n c i e nt C h i n a A T E A C H E R ’ S G U I D E The Art and Archaeology of Ancient China A T E A C H ER’S GUI DE PROJECT DIRECTOR Carson Herrington WRITER Elizabeth Benskin PROJECT ASSISTANT Kristina Giasi EDITOR Gail Spilsbury DESIGNER Kimberly Glyder ILLUSTRATOR Ranjani Venkatesh CALLIGRAPHER John Wang TEACHER CONSULTANTS Toni Conklin, Bancroft Elementary School, Washington, D.C. Ann R. Erickson, Art Resource Teacher and Curriculum Developer, Fairfax County Public Schools, Virginia Krista Forsgren, Director, Windows on Asia, Atlanta, Georgia Christina Hanawalt, Art Teacher, Westfield High School, Fairfax County Public Schools, Virginia The maps on pages 4, 7, 10, 12, 16, and 18 are courtesy of the Minneapolis Institute of Arts. The map on page 106 is courtesy of Maps.com. Special thanks go to Jan Stuart and Joseph Chang, associate curators of Chinese art at the Freer and Sackler galleries, and to Paul Jett, the museum’s head of Conservation and Scientific Research, for their advice and assistance. Thanks also go to Michael Wilpers, Performing Arts Programmer, and to Christine Lee and Larry Hyman for their suggestions and contributions. This publication was made possible by a grant from the Freeman Foundation. The CD-ROM included with this publication was created in collaboration with Fairfax County Public Schools. It was made possible, in part, with in- kind support from Kaidan Inc. -

Origin Narratives: Reading and Reverence in Late-Ming China

Origin Narratives: Reading and Reverence in Late-Ming China Noga Ganany Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2018 © 2018 Noga Ganany All rights reserved ABSTRACT Origin Narratives: Reading and Reverence in Late Ming China Noga Ganany In this dissertation, I examine a genre of commercially-published, illustrated hagiographical books. Recounting the life stories of some of China’s most beloved cultural icons, from Confucius to Guanyin, I term these hagiographical books “origin narratives” (chushen zhuan 出身傳). Weaving a plethora of legends and ritual traditions into the new “vernacular” xiaoshuo format, origin narratives offered comprehensive portrayals of gods, sages, and immortals in narrative form, and were marketed to a general, lay readership. Their narratives were often accompanied by additional materials (or “paratexts”), such as worship manuals, advertisements for temples, and messages from the gods themselves, that reveal the intimate connection of these books to contemporaneous cultic reverence of their protagonists. The content and composition of origin narratives reflect the extensive range of possibilities of late-Ming xiaoshuo narrative writing, challenging our understanding of reading. I argue that origin narratives functioned as entertaining and informative encyclopedic sourcebooks that consolidated all knowledge about their protagonists, from their hagiographies to their ritual traditions. Origin narratives also alert us to the hagiographical substrate in late-imperial literature and religious practice, wherein widely-revered figures played multiple roles in the culture. The reverence of these cultural icons was constructed through the relationship between what I call the Three Ps: their personas (and life stories), the practices surrounding their lore, and the places associated with them (or “sacred geographies”).