1855 Cornwall Quarter Sessions and Assizes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Great Western Railway Ships - Wikipedi… Great Western Railway Ships from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

5/20/2011 Great Western Railway ships - Wikipedi… Great Western Railway ships From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The Great Western Railway’s ships operated in Great Western Railway connection with the company's trains to provide services to (shipping services) Ireland, the Channel Islands and France.[1] Powers were granted by Act of Parliament for the Great Western Railway (GWR) to operate ships in 1871. The following year the company took over the ships operated by Ford and Jackson on the route between Wales and Ireland. Services were operated between Weymouth, the Channel Islands and France on the former Weymouth and Channel Islands Steam Packet Company routes. Smaller GWR vessels were also used as tenders at Plymouth and on ferry routes on the River Severn and River Dart. The railway also operated tugs and other craft at their docks in Wales and South West England. The Great Western Railway’s principal routes and docks Contents Predecessor Ford and Jackson Successor British Railways 1 History 2 Sea-going ships Founded 1871 2.1 A to G Defunct 1948 2.2 H to O Headquarters Milford/Fishguard, Wales 2.3 P to R 2.4 S Parent Great Western Railway 2.5 T to Z 3 River ferries 4 Tugs and work boats 4.1 A to M 4.2 N to Z 5 Colours 6 References History Isambard Kingdom Brunel, the GWR’s chief engineer, envisaged the railway linking London with the United States of America. He was responsible for designing three large ships, the SS Great Western (1837), SS Great Britain (1843; now preserved at Bristol), and SS Great Eastern (1858). -

Luxulyan Lockingate Infant School Admissions

Admissions to Lockingate Infant School, Luxulyan Transcribed from LDS Film No. 1471658 by Phil Rodda Exempt indicates whether exempt from religious instruction Admission Forename(s) Surname DoB Parent/ Abode Exempt Last School Date of Register Notes Transcriber Notes No. Date Year Guardian leaving 124‐May 1880 Edith COAD 04/08/1972 Jeremiah Lockingate No Dames 04/05/1884 224‐May 1880 Amy COAD 25/03/1875 Jeremiah Lockingate No Dames 03/05/1884 324‐May 1880 Peter WELLINGTON 21/10/1873 John Harres No Dames 04/05/1884 424‐May 1880 William WELLINGTON 17/09/1872 John Harres No Dames 04/05/1884 524‐May 1880 Freddy WELLINGTON 02/05/1876 John Harres No Dames 04/05/1884 624‐May 1880 John RETALLICK 19/09/1872 William Savath No Dames 04/05/1884 725‐May 1880 Elizabeth STACEY 19/06/1873 William Crift No Dames 01/06/1886 825‐May 1880 Selina STACEY 01/04/1875 William Crift No Dames 13/05/1887 925‐May 1880 Edith KNIGHT 14/06/1873 William Woon Bar No Dames 04/05/1884 10 26‐May 1880 Alfred STONEMAN 02/03/1875 Thomas Gillis No Dames 04/05/1884 11 31‐May 1880 Mary E. TRETHEWEY 02/04/1872 Joseph Trescoll No Dames 04/05/1884 12 31‐May 1880 John TRETHEWEY 23/09/1874 Joseph Trescoll No Dames 03/05/1884 13 31‐May 1880 Willie STONEMAN 12/11/1874 John Trescoll No None 03/05/1984 14 31‐May 1880 Daniel GREEN 04/12/1873 Thomas Caunce No None Left June 15 31‐May 1880 Hetty GREEN 15/09/1872 Thomas Caunce No None Left 16 07‐Jun 1880 Frederick COCKS 04/05/1873 John Lockingate No Dames 04/05/1884 17 07‐Jun 1880 Mary E. -

Licensing-Residential Premises

Cornwall Council Licensing and Management of Houses in Multiple Occupation WARD NAME: Bodmin East Licence Reference HL12_000169 Licence Valid From 05/04/2013 Licence Address 62 St Nicholas StreetBodminCornwallPL31 1AG Renewal Date 05/04/2018 Applicant Name Mr Skea Licence Status Issued Applicant Address 44 St Nicholas StreetBodminCornwallPL31 1AG Licence Type HMO Mandatory Agent Full Name Type of Construction: Semi-Detatched Agent Address Physical Construction: Solid wall Self Contained Unit: Not Self Contained Number of Floors: 3 Number of Rooms Let 10 Permitted Occupancy: Baths and Showers: 3 Cookers: Foodstores: 9 Sinks: Wash Hand Basins: 3 Water Closets: 3 WARD NAME: Bude North And Stratton Licence Reference HL12_000141 Licence Valid From 05/09/2012 Licence Address 4 Maer DownFlexburyBudeCornwallEX23 8NG Renewal Date 05/09/2017 Applicant Name Mr R Bull Licence Status Issued Applicant Address 6 Maer DownFlexburyBudeCornwallEX23 8NG Licence Type HMO Mandatory Agent Full Name Type of Construction: Semi-Detatched Agent Address Physical Construction: Solid wall Self Contained Unit: Not Self Contained Number of Floors: 3 Number of Rooms Let 10 Permitted Occupancy: Baths and Showers: 6 Cookers: Foodstores: Sinks: Wash Hand Basins: 12 Water Closets: 8 16 May 2013 Page 1 of 85 Licence Reference HL12_000140 Licence Valid From 05/09/2012 Licence Address 6 Maer DownFlexburyBudeCornwallEX23 8NG Renewal Date 05/09/2017 Applicant Name Mr R.W. Bull Licence Status Issued Applicant Address MoorhayAshwaterBeaworthyDevonEX21 5DL Licence Type HMO Mandatory Agent Full Name Type of Construction: Semi-Detatched Agent Address Physical Construction: Solid wall Self Contained Unit: Not Self Contained Number of Floors: 3 Number of Rooms Let 8 Permitted Occupancy: Baths and Showers: 8 Cookers: 8 Foodstores: Sinks: Wash Hand Basins: 7 Water Closets: 9 Licence Reference HL12_000140 Licence Valid From 05/09/2012 Licence Address 6 Maer DownFlexburyBudeCornwallEX23 8NG Renewal Date 05/09/2017 Applicant Name Mr R.W. -

DIRECTIONS to WOOLGARDEN from the A30 WESTBOUND (M5/Exeter)

DIRECTIONS TO WOOLGARDEN FROM THE A30 WESTBOUND (M5/Exeter) About 2 miles beyond Launceston, take the A395 towards Camelford and Bude. After 10 minutes you come to Hallworthy, turn left here, opposite the garage and just before the Wilsey Down pub: - Continue straight on for 2 miles. The postcode centre (PL15 8PT) is near a T-junction with a triangular patch of grass in the middle. Continue round to the left at this point: - Continue for about a quarter mile down a small dip and up again. You will the come to a cream- coloured house and bungalow on the right. The track to Woolgarden is immediately after this on the same side, drive a short distance down the track and you have arrived! DIRECTIONS TO WOOLGARDEN FROM CORNWALL AND PLYMOUTH From Bodmin, Mid and West Cornwall: Follow the A30 towards Launceston. Exit the A30 at Five Lanes, as you descend from Bodmin Moor, then follow the directions below. From Plymouth & SE Cornwall: Follow the A38 to Saltash then the A388 through Callington, then soon afterwards fork left onto the B2357, signposted Bodmin. (Or from Liskeard direction, take the B3254 towards Launceston, then turn left onto the B3257 at Congdons Shop.) Then at Plusha join the A30 towards Bodmin and then come off again the first exit, Five Lanes, then follow the directions below. In the centre of Five Lanes (Kings Head pub), follow signs to Altarnun and Camelford: - Continue straight on, through Altarnun, for about 1.5 miles, then turn left at the junction, signposted Camelford. Soon afterward, keep the Rinsing Sun pub on your left:- After a mile, turn right at the crossroads, signposted St Clether and Hallworthy: - And after another mile, go straight across the crossroad: - A half mile further on, you will pass Tregonger farm on your right, and then see a cream coloured bungalow on your left. -

Saltash Floating Bridge Saltash Passage and D-Day, 6 June 1944

SALTASH PASSAGE altash Passage and nearby Little Ash were once part of Cornwall – although they have both always been Saltash Floating Bridge within the Devonshire parish of St Budeaux. For over 600 years there was an important ferry crossing here, The Royal Albert Bridge Devon born civil engineer James Meadows Rendel moved to Plymouth in the Sto Saltash. A major problem in taking the steam railway west from Plymouth and on into early 1820s. His Saltash Floating Bridge was Plymouth-built and entered service From 1851, and for 110 years, the Saltash Ferry was served by a powered floating bridge or chain ferry. Saltash Cornwall was crossing the River Tamar. In 1848, Isambard Kingdom Brunel in early 1833. The machinery was in the middle, with a deck either side for foot proposed a viaduct at Saltash, where the river is just 335 metres (1,100ft) wide. passengers, horses and livestock, or up to four carriages. Because of the strong Corporation held the ferry rights for much of that time. There were seven floating bridges in total and the last The final agreed design was for a wrought iron, bow string suspension bridge; current, the fixed chain and ferry crossed the river at an angle. Rendel’s Saltash ferry crossed here in October 1961. part arched bridge, part suspension bridge – with the roadway suspended from Ferry was pioneering but unreliable. It was withdrawn in months and the old The Saltash Viaduct is better known as the Royal Albert Bridge. It was designed by Isambard Kingdom Brunel in two self-supporting tubular trusses. -

3 Bolingey Chapel, Chapel Hill Guide Price £177,500

3 Bolingey Chapel, Chapel Hill Bolingey, Perranporth, TR6 0DQ • No Chain Guide Price £177,500 • Ideal letting investment EPC Rating ‘51’ • Great as a second home • Good first purchase 3 Bolingey Chapel, Chapel Hill, Bolingey, Perranporth, TR6 0DQ Property Description This two double bedroom apartment is set in a chapel conversion located in the desirable hamlet of Bolingey and just one mile from the renowned golden sands of the beach at Perranporth. Having upvc double glazing and electric heating, this individual first floor apartment enjoys communal gardens and level residents parking. Enjoying rural views from the majority of windows, there is a communal access stairway, then a private hallway, two double bedrooms and modern kitchen with open access to the generous living/dining room. The bathroom also contains a separate shower cubicle in addition to a bath and the property would prove an ideal holiday or residential let as well as an excellent first purchase or second home. LOCATION Bolingey is an attractive hamlet with public house, situated approximately a 1/2 mile from Perranporth and a mile from its beach. Perranporth offers an excellent range of facilities including primary schooling and a range of shops, bars and bistros and is particularly popular for its large sandy beach renowned for its surfing conditions. Communal stairs rising to the first floor. Entrance door leading into: - ENTRANCE VESTIBULE With door to:- LOUNGE/DINING ROOM 19' 1" x 9' 4" (5.84m x 2.86m) plus recesses. Dual aspect with rural outlook from both windows. Wood effect flooring. Electric fire. Dining recess. KITCHEN 11' 8" x 6' 6" (3.57m x 2.0m) With an excellent range of base, wall and drawer units with roll edge work surface having inset 1 1/2 basin sink unit. -

St Hilary Neighbourhood Development Plan

St Hilary Neighbourhood Development Plan Survey review & feedback Amy Walker, CRCC St Hilary Parish Neighbourhood Plan – Survey Feedback St Hilary Parish Council applied for designation to undertake a Neighbourhood Plan in December 2015. The Neighbourhood Plan community questionnaire was distributed to all households in March 2017. All returned questionnaires were delivered to CRCC in July and input to Survey Monkey in August. The main findings from the questionnaire are identified below, followed by full survey responses, for further consideration by the group in order to progress the plan. Questionnaire responses: 1. a) Which area of the parish do you live in, or closest to? St Hilary Churchtown 15 St Hilary Institute 16 Relubbus 14 Halamanning 12 Colenso 7 Prussia Cove 9 Rosudgeon 11 Millpool 3 Long Lanes 3 Plen an Gwarry 9 Other: 7 - Gwallon 3 - Belvedene Lane 1 - Lukes Lane 1 Based on 2011 census details, St Hilary Parish has a population of 821, with 361 residential properties. A total of 109 responses were received, representing approximately 30% of households. 1 . b) Is this your primary place of residence i.e. your main home? 108 respondents indicated St Hilary Parish was their primary place of residence. Cornwall Council data from 2013 identify 17 second homes within the Parish, not including any holiday let properties. 2. Age Range (Please state number in your household) St Hilary & St Erth Parishes Age Respondents (Local Insight Profile – Cornwall Council 2017) Under 5 9 5.6% 122 5.3% 5 – 10 7 4.3% 126 5.4% 11 – 18 6 3.7% 241 10.4% 19 – 25 9 5.6% 102 4.4% 26 – 45 25 15.4% 433 18.8% 46 – 65 45 27.8% 730 31.8% 66 – 74 42 25.9% 341 14.8% 75 + 19 11.7% 202 8.8% Total 162 100.00% 2297 100.00% * Due to changes in reporting on data at Parish level, St Hilary Parish profile is now reported combined with St Erth. -

Camelford Exploration and Research

Out and about Local attractions Welcome to •Boscastle Visitor Centre There is much to enjoy at Boscastle and the Visitor Centre should be your first port of call for all the information you need to discover the opportunities for further local Camelford exploration and research. 01840 250010 www.visitboscastleandtintagel.com Caravan Club Site •Bodmin & Wenford •Lanhydrock House and Garden Steam Railway One of the most beautiful National Trust Discover the excitement and nostalgia of properties in Cornwall, Lanhydrock House steam travel with a journey back in time and gardens are a must-see all year round. on the Bodmin & Wenford Railway Superbly set in wooded parkland of 1,000 – Cornwall’s only full-size railway still acres and encircled by a garden of rare operated by steam locomotives. shrubs and trees. 0845 125 9678 01208 265950 www.bodminandwenfordrailway.co.uk www.nationaltrust.org.uk •The Eden Project With a worldwide reputation Eden barely •Carnglaze Slate Caverns needs an introduction, but this epic Three underground caverns set in 6.5 destination definitely deserves a day of acres of wooded hillside of the Loveny your undivided attention. Dubbed the Valley. Take a tour through the caverns ‘8th Wonder of the World’, there’s always of cathedral proportions, hand-created something new to see – go again & again! by local slate miners. Within the complex 01726 811911 is the famous subterranean lake with its www.edenproject.com crystal clear blue/green water. 01579 320251 •Pencarrow House & Gardens www.carnglaze.com 50 acres of beautiful grounds – the perfect place for everyone including the dog! Also an Historic Georgian house Activities containing a superb collection of pictures, Get to know your site furniture and porcelain. -

Cornwall. Pub 1445

TRADES DIRECTORY.] CORNWALL. PUB 1445 . Barley Sheaf, Mrs. Mary Hawken, Lower Bore st. Bodmin Commercial hotel,John Wills,Dowugate,Linkiuhorne,Liskrd Barley Sheaf, Mrs. Elizabeth Hill, Church street, Liskeard Commercial hotel & posting house, Abraham Bond, Gunnis~ Barley Sheaf inn, Fred Liddicoat, Union square, St. Columb lake, Tavistock Major R.S.O Commercial hotel & posting establishment (Herbert Henry Barley Sheaf hotel, Mrs. Elizh. E. Reed, Old Bridge st. Truro Hoare, proprietor), Grampound Road Barley Sheaf, William Richards, Gorran, St. Austell Commercial hotel, family, commercial & posting house, Basset Arms, William Laity, Basset road, Camborne William Alfred Holloway, Porthleven, Helston Basset Arms, Solomon Rogers, Pool, Carn Brea R.S. 0 Commercial hotel, family, commercial & posting, Richard Basset Arms, Charles Wills, Portreath, Redruth Lobb. South quay, Padstow R.S.O Bay Tree, Mrs. Elizabeth Rowland, Stratton R.S.O Cornish Arms, Thomas Butler, Crockwell street, Bodmin .Bennett's Arms, Charles Barriball, Lawhitton, Launceston Cornish Arms, Jarues Collins, Wadebridge R.S.O Bell inn, William Ca·rne, Meneage street, Helston Cornish Arms, Mrs. Elizh. Eddy, Market Jew st. Penzance Bell inn, Daniel Marshall, Tower street, Launceston Cornish Arms, Jakeh Glasson, Trelyon, St. Ives R.S.O Bell commercial hotel & posting house, Mrs. Elizabeth Cornish Arms, Nicholas Hawken, Pendoggett, St. Kew, Sargent, Church street, Li.skeard Wadebridge R.S.O Bideford inn, Lewis Butler, l:ltratton R.S. 0 Cornish Arms, William LObb, St. Tudy R.S.O Black Horse, Richard Andrew, Kenwyn street, Truro CornishArms,Mrs.M.A. Lucas,St. Dominick,St. MellionR. S. 0 BliBland inn, Mrs. R. Williams, Church town,Blislaud,Bodmin Cornish Arms, Rd. -

Cognition and Learning Schools List

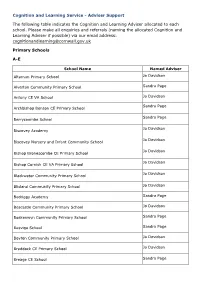

Cognition and Learning Service - Adviser Support The following table indicates the Cognition and Learning Adviser allocated to each school. Please make all enquiries and referrals (naming the allocated Cognition and Learning Adviser if possible) via our email address: [email protected] Primary Schools A-E School Name Named Adviser Jo Davidson Altarnun Primary School Sandra Page Alverton Community Primary School Jo Davidson Antony CE VA School Sandra Page Archbishop Benson CE Primary School Sandra Page Berrycoombe School Jo Davidson Biscovey Academy Jo Davidson Biscovey Nursery and Infant Community School Jo Davidson Bishop Bronescombe CE Primary School Jo Davidson Bishop Cornish CE VA Primary School Jo Davidson Blackwater Community Primary School Jo Davidson Blisland Community Primary School Sandra Page Bodriggy Academy Jo Davidson Boscastle Community Primary School Sandra Page Boskenwyn Community Primary School Sandra Page Bosvigo School Boyton Community Primary School Jo Davidson Jo Davidson Braddock CE Primary School Sandra Page Breage CE School School Name Named Adviser Jo Davidson Brunel Primary and Nursery Academy Jo Davidson Bude Infant School Jo Davidson Bude Junior School Jo Davidson Bugle School Jo Davidson Burraton Community Primary School Jo Davidson Callington Primary School Jo Davidson Calstock Community Primary School Jo Davidson Camelford Primary School Jo Davidson Carbeile Junior School Jo Davidson Carclaze Community Primary School Sandra Page Cardinham School Sandra Page Chacewater Community Primary -

The Boulton and Watt Archive and the Matthew Boulton Papers from Birmingham Central Library Part 12: Boulton & Watt Correspondence and Papers (MS 3147/3/179)

INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION: A DOCUMENTARY HISTORY Series One: The Boulton and Watt Archive and the Matthew Boulton Papers from Birmingham Central Library Part 12: Boulton & Watt Correspondence and Papers (MS 3147/3/179) DETAILED LISTING REEL 199 3/4 Letters to James Watt, 1780 (44 items) Letters from Matthew Boulton to James Watt from 1780. The bundle also contains three letters from Logan Henderson to James Watt. 1. Letter. Matthew Boulton (York) to James Watt (Birmingham). 8 Mar. 1780. Summarised “Concerning the signing of Fenton’s articles. Also the copying business. Boulton going to Newcastle.” 2. Letter. Matthew Boulton (London) to James Watt (—). 6 Apr. 1780. Misdated by Boulton as Mar. Summarised “York Building Water Works require an engine. Smeaton’s failure with wooden piston. Concerning the copying scheme.” 3. Letter. Matthew Boulton (London) to James Watt (Birmingham). “Saturday night” 8 Apr. 1780. On the same sheet: Memorandum. “York Building Western Engine. Query respecting the Erection of a new engine to raise 55,600 cubic feet in 8 hours.” 7 Apr. 1780. Summarised “Calculations of size of York Buildings engine. Dr. Roebuck almost insists that his son becomes partner. Copying scheme.” 4. Letter. Matthew Boulton (London) to James Watt (—). 10 Apr. 1780. Docketed “About Mr. Wiss’s affairs.” Summarised “Copying scheme. York Building Water Works calculations. Concerning dividing money matters.” 5. Letter. Matthew Boulton (London) to James Watt (Birmingham). 17 Apr. 1780. On the same sheet: Letter. James Keir (London) to James Watt (Birmingham). 17 Apr. 1780. Summarised “Letter from Keir with information re. copying scheme, and the naval metal. -

Analysis of Surface Water Flood Risks Within the Cornwall Lead Local Flood Authority (LLFA) Area

Cornwall Council Preliminary Flood Risk Assessment ANNEX 6 – Analysis of Surface Water Risk June 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ..............................................................................................i LIST OF FIGURES......................................................................................................i LIST OF TABLES........................................................................................................i 1 INTRODUCTION............................................................................................... 1 2 ENVIRONMENT AGENCY METHODOLOGY ................................................... 2 3 CORNWALL COUNCIL METHODOLOGY ........................................................ 6 3.1 Grid-based approach ................................................................................. 6 3.2 Community-based approach .................................................................... 13 LIST OF FIGURES Figure A1 Five touching blue squares within 3x3 km grid.................................................... 3 Figure A2 Indicative flood risk areas for England................................................................. 3 Figure A3 Potential flood risk areas based on EA analysis.................................................. 4 Figure A4 Potential flood risk areas based on EA and Cornwall Council analyses ............. 5 Figure A5 Origins of the each of the grids used in the sensitivity analysis .......................... 7 Figure A6 Grid squares and clusters