Devi! on the Fiddle": the Musical and Social Ramifications of Genre Transformation in Cape Breton Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Backgrounder.Pdf

Backgrounder March 31, 2016 Universal Music Canada donates archive of music label EMI Music Canada to University of Calgary Partnership with National Music Centre offers public access for education and celebration of music On March 31, 2016, the University of Calgary announced a gift from Universal Music Canada of the complete archive of EMI Music Canada. Universal Music Canada acquired the archive when Universal Music Group purchased EMI Music in 2012. The University of Calgary has partnered with the National Music Centre (NMC) to collaborate on opportunities for the public to celebrate music in Canada through educational programming and exhibitions that highlight the archive at NMC’s new facility, Studio Bell. This partnership began with NMC’s critical role in connecting the university with Universal Music Canada. The EMI Music Canada Archive will be accessible to students, researchers and music fans in Calgary and around the world. The University of Calgary has also partnered with the National Music Centre to collaborate on opportunities for the public to celebrate music in Canada through educational programming and exhibitions that highlight the archive. About the EMI Music Canada Archive The EMI Music Canada Archive documents 63 years of the music industry in Canada, from 1949 to 2012. The collection consists of 5,500 boxes containing more than 18,000 video recordings, 21,000 audio recordings and more than two million documents and photographs. More than 40 different recording formats are represented: quarter‐inch, half‐inch, one‐inch and two‐inch reel‐to‐reel tapes, U‐matic tapes, film, DATs, vinyl, Betacam, VHS, cassette tapes, compact discs and DVDs. -

Natalie Macmaster and Donnell Leahy a Celtic Family Christmas Wednesday, December 13, 2017 7:30 Pm

Natalie MacMaster and Donnell Leahy A Celtic Family Christmas Wednesday, December 13, 2017 7:30 pm 45TH ANNIVERSARY SEASON 2017/2018 Great Artists. Great Audiences. Hancher Performances. The Band: Mac Morin (piano) Mark Kelso (drums) Elmer Ferrer (guitar) Rémi Arsenault (bass/guitar) Program to be announced from the stage 3 Give the gift of music this holiday season! EVENT SPONSOR DEBORAH K. AND IAN E. BULLION DARYL K. AND NANCY J. GRANNER DR. JOHN P. MEHEGAN AND DR. PAMELA K. GEYER PHELAN, TUCKER, MULLEN, WALKER, TUCKER & GELMAN, L.L.P. TOM ROCKLIN AND BARBARA ALLEN UNIVERSITY OF IOWA COMMUNITY CREDIT UNION SEASON SPONSOR WEST MUSIC westmusic.com Cedar Falls • Cedar Rapids • Coralville Decorah • Des Moines • Dubuque • Quad Cities PROUD to be Hancher’s 2017-2018 Season Sponsor! Photo: Miriam Alarcón Avila Give the gift of music this holiday season! westmusic.com Cedar Falls • Cedar Rapids • Coralville Decorah • Des Moines • Dubuque • Quad Cities PROUD to be Hancher’s 2017-2018 Season Sponsor! ABOUT THE ARTISTS To fans of fiddle music, NATALIE MACMASTER needs no introduction. Over a recording career now spanning 25 years, this Order of Canada recipient has released 11 albums that have notched sales of over 200,000 copies. She has won two JUNO and eleven East Coast Music Awards and been nominated for a Grammy, and has collaborated with artists as diverse as Yo-Yo Ma (on the Grammy-winning album Songs of Joy & Peace), Alison Krauss, Jesse Cook, and Béla Fleck. Though acknowledging that she can be "a musical chameleon," Natalie stresses that, above all else, "I play Cape Breton fiddle." DONNELL LEAHY is no stranger to the awards podium himself. -

Artsnews SERVING the ARTS in the FREDERICTON REGION April 19, 2018 Volume 19, Issue 16

ARTSnews April 19, 2018 Volume 19, Issue 16 ARTSnews SERVING THE ARTS IN THE FREDERICTON REGION April 19, 2018 Volume 19, Issue 16 In this issue *Click the “Back to top” link after each notice to return to “In This Issue”. Upcoming Events 1. Upcoming Events at Grimross Brewing Co. Apr 21- 2. Music Runs Though It presents Morgan Davis at Corked Wine Bar Apr 19 3. Early History of Fredericton Police Force Subject of Lecture 4. The Shoe Project presents In Our Shoes Apr 20 5. Screening of The Capital Project Documentary Apr 20 6. Self-Portrait Exhibition opens at Gallery 78 Apr 20 7. NBCS presents NB Country Showcase at The Playhouse Apr 21 8. The Fredericton North Heritage Association hosts Heritage Fair Apr 21 9. Upcoming Events at the Beaverbrook Art Gallery Apr 22 & 29 10. Fredericton Ukulele Club Apr 22 11. Gospel Side of Elvis at Wilmot United Church Apr 22 12. The Combine & Black Moor at The Capital Apr 23 13. Monday Night Film Series presents C’est La Vie! (Arp 23) & Death of Stalin (Apr 30) 14. Stephen Lewis & Friends Tour Kick Off at Wilser’s Room Apr 25 15. Poetry Month Celebration hosted by Cultural Laureate Ian LeTourneau Apr 26 16. Disney’s Beauty and the Beast at the Playhouse Apr 26-28 17. Bel Canto Singers East CoastCoach Kitchen Party Apr 28 18. House Concert with Adyn Townes Apr 28 19. Fredericton Finds Films Apr 28 20. Marx in Soho at the Black Box Theatre Apr 28 & 29 21. Heather Rankin Forges Her Own Musical Legacy while Honouring Her Roots Apr 29 22. -

Natalie Macmaster with Natalie Macmaster Fiddle Mac Morin Piano Shane Hendrickson Bass Eric Breton Percussion Nate Douglas Guitar

Rebekah Littlejohn Photography Rebekah Natalie MacMaster with Natalie MacMaster Fiddle Mac Morin Piano Shane Hendrickson Bass Eric Breton Percussion Nate Douglas Guitar PROGRAM There will be an intermission. Set list will be announced from stage. Friday, March 15 at 7:30 PM Zellerbach Theatre 12/13 Season | 19 ABOUT THE ARTISTS Natalie MacMaster Natalie MacMaster is a member of the Order of Canada as well as a Juno award winner. She has released 11 albums, the majority of which have reached gold status (50,000 records sold). MacMaster received an honorary doctorate from St. Thomas University and honorary degrees from Niagara University, NY and Trent University. MacMaster is best known as a virtuoso fiddler, thrilling audiences around the world – including those at Carnegie Hall and Massey Hall—with her invigorating prowess while serving as a music ambassador to her beloved traditional Cape Breton sound. Married to fellow fiddler Donnell Leahy of Leahy, the mother of four performs an average of 100 dates a year and co-hosts the annual Leahy Music Camp with her husband and his band in Lakefield, Ontario. MacMaster has appeared multiple times on the CBC,Canada A.M. and Garrison Keillor’s A Prairie Home Companion. She has also warmed the hearts of TV viewers with guest spots on Christmas specials like Rita MacNeil’s Christmas and Holiday Festival On Ice with Olympic ice skaters Jamie Sale, David Pelletier, Kurt Browning and world champion Jeffrey Buttle. MacMaster’s talents have also been in-demand by her peers, contributing to albums by Ma, The Chieftains, children’s entertainer Raffi, banjo prodigy Béla Fleck, fellow fiddling marvel Alison Krauss (with whom MacMaster played a duet on Krauss’sA Hundred Miles Or More: A Collection), Dobro specialist Jerry Douglas, singer Hayley Westenra, former Doobie Brother and classic R&B interpreter Michael McDonald and most recently, Thomas Dolby’s new album Map Of The Floating City. -

Nationals Editorials Organizers Receive Praise for Accomplishments Take a Look at Yourself

,' ><gjv '^•;:<"t^<.-i^^-;;-j:j5i^,Kv^^,j LETHBRIOqr COMMUNrTyCOlliQE Published by students of the Communication Arts Program Vol. XXVIII - No. 15 Thursda)^ March 17,1994 m / jm This Week: 1 Nationals Editorials Organizers receive praise for accomplishments Take a look at yourself. Ever wonder why you By Dennis Barnes always wear green this time ofthe year? LCC is hosting one ofthe most well 4 organized CCAA Titrex National Basketball championships ever, says a toumament organization member, Features John Jasiukiewicz. He also added Caricature artist's pen LCC has done a super job getting the swells heads at LCC. championships ready. "Ticket sales are going well above Later he tickles some our expectations," says Ann Raslask, funny bones. toumament public relations co 8 ordinator. She expects tickets to be sold outbefore the toumamentis over. Sports "We are very pleased with the sale of over 600 advanced tickets because Kodiaks capture ACAC it should ensure a full gymnasium basketball champion every night to see the games," Raslask ship to the joy of a minor says. "Prices for the tickets were kept as official making a minor reasonable as possible to ensure most mistake. people couldfifford to attend as many 13 of the games ais possible," says Tim Tollestrup, Athletic Director for LCC. Close to 1500 people including Entertainment volunteers, players, coaches, trainers, team staffmembers, officials and LCC The Hankin Family is maintenance staff are involved and coming to Lethbridge. are responsible for the success ofthe Get the highhghts. event. Approximately 400 are 16 volunteers from the LCC student population and staff members. -

Cape Breton Girl: Performing Cape Breton at Home and Away with Natalie Macmaster

Cape Breton Girl: Performing Cape Breton at Home and Away with Natalie MacMaster KATHRYN ALEXANDER Abstract: Normative gendered and ethnic Scottish Cape Bretoner identity is constructed through traditional music and dance performance and practice. This article examines how Natalie MacMaster 43 (1): 89-111. 43 (1): constructs her gendered and ethnic identities as normative and quintessentially Cape Breton through her stage performances both on the island and internationally. The vision of Scottish Cape Bretonness she crafts shapes the perceptions and expectations of Cape Breton held by non-islander consumers of the MUSICultures island’s Scottish culture. As an unofficial cultural ambassador, MacMaster’s every performance, at home and away, becomes a tourism encounter that ties Cape Bretonness to ethnic whiteness, traditionalism, and heteronormativity. Résumé : L’identité écossaise de Cap Breton, pour ce qui est de la normativité du genre et de l’ethnicité, se construit au moyen de la performance et de la pratique de la musique et de la danse traditionnelles. Cet article examine la façon dont Natalie MacMaster construit son identité de genre et son identité ethnique dans une normativité typique du Cap Breton par le biais de ses spectacles, tant sur l’île qu’au niveau international. La représentation qu’elle donne du caractère écossais de Cap Breton façonne les perceptions qu’ont de l’île les consommateurs non insulaires, et leurs attentes au sujet de la culture écossaise de l’île. En tant qu’ambassadrice culturelle non officielle, chaque performance de MacMaster, tant dans son île qu’à l’étranger, devient une rencontre touristique qui lie l’identité de Cap Breton à l’ethnicité blanche, au traditionalisme et à l’hétéro-normativité. -

The Rankin Family Live at the Red Robinson Show Theatre

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE OCTOBER 11, 2011 BOULEVARD CASINO PRESENTS THE RANKIN FAMILY LIVE AT THE RED ROBINSON SHOW THEATRE FRIDAY, JANUARY 27 Coquitlam, BC – It was in 1989 when Cape Breton siblings – Raylene, John Morris, Jimmy, Cookie and Heather Rankin – began touring together professionally when just a year later with the independent release of their second recording, Fare Thee Well Love, they were signed to Capitol/EMI Music. After the label re-released the album in 1992, it quickly went on to become a platinum seller with the title track finding its way to the Disney film, Into the West. The following year, they released North Country which featured the popular title track along with “Borders and Time” resulting in another-multi platinum success for The Rankin Family. Their music crossed over many musical styles earning them a fast growing following as well as industry accolades that included six Juno Awards and fifteen East Coast Music Awards. Both Grey Dusk of Eve and Endless Seasons were released in 1995 followed by Heather, Cookie and Raylene’s best-selling Christmas album, Do You Hear What I Hear. In 1998, the group released their final album together … aptly titled Uprooted. The following year, they decided to go their separate ways … each pursuing their own interests and musical projects. It wasn’t until eight years later that in 2007, they released their Reunion album and the family soon set out on a cross-Canada tour with niece Molly Rankin – daughter of the late John Morris – completing the line-up. It was as though no time had passed … night after night, audiences welcomed them back into the fold. -

Sunset Side of Cape Breton Island

2014 ACTIVITY 2014 ActivityGUIDE Guide Page 1 SUNSET of Cape Breton SIDE • Summer Festivals • Scottish Dances • Kayaking • Hiking Trails • Horse Racing • Golf • Camping • Museums • Art Galleries • Great Food • Accommodations • Outdoor Concerts and more... WELCOME HOME www.invernesscounty.ca Page 2 2014 Activity Guide A must see during your visit to Discover Cape Breton Craft our Island is the Cape Breton Centre for Craft & Design in Art and craft often mirror the downtown Sydney. The stunning heritage, lifestyle and geography Gallery Shop contains the work of the region where artists live of over 70 Cape Breton artisans. and work. Nowhere is this more Hundreds of unique and one- evident than on Cape Breton of-a-kind items are on display Island with its stunning landscapes, and available for purchase. The rich history and traditions that Centre also hosts exhibitions have fostered a dynamic creativity and a variety of craft workshops Visual Artist Kenny Boone through the year. among its artisans. Fabric Dyeing by the Sea - Ann Schroeder Discover the connections between Cape Breton’s culture and Craft has a celebrated history geography and the work of our artisans by taking to the road with on our Island and, in many the Cape Breton Artisan Trail Map or download the App. Both will communities, craft remains set you on a trail of discovery and beauty with good measures of a living tradition among culture, history, adventure and charm. contemporary artisans who honour and celebrate both Artful surprises can be found tucked in the nooks and crannies form and function in endlessly throughout the Island: Raku potters on the North Shore, visual artists creative ways. -

MOTHER NATURE SMILES on KSW!!!!

Make Your Plans for the Founder’s Day Cornroast and Family Picnic, on August 25th!!! ISSUE 16 / SUMMER ’12 Bill Parsons, Editor 6504 Shadewater Drive Hilliard, OH 43026 513-476-1112 [email protected] THE NEWSLETTER OF THE CALEDONIAN SOCIETY OF CINCINNATI In This Issue: Nature Smiles on KSW 1 MOTHER NATURE SMILES on KSW!!!! Cornroast Aug 25th 2 *Schedule of Events 2 ust in case you did not attend the 30th Annual Kentucky Scottish Scotch Ice Cream? 3 JWeekend on the 12th of May, here CSHD 3 is what you missed. First off, a perfectly Cinti Highld Dancers 3 grand sunny day (our largest crowd Nessie Banned in WI 4 over the last three years); secondly, *Resource List 4 the athletics, Scottish country dancing, highland dancing, clogging, Seven Assessment KSW? 5 Nations, Mother Grove, the Border Scottish Unicorns 5 Collies, British Cars, Clans, and Pipe Glasgow Boys ’n Girls 6-11 Bands. This year we had a new group *Email PDF Issue only* called “Pictus” perform and we added a welly toss for the children. Colours Glasgow Girls 8* were posted by the Losantiville Scots on FIlm-BRAVE 12* Highlanders. Out of the Sporran 13* Food and drink. For the first time, the Park served beer and wine in the “Ole Scottish Pub”. Food vendors PAY YOUR DUES! included barbecue, meat pies, fish and Don’t forget to pay your current chips, gourmet ice cream, and bakery dues. You will not be able to vote goods galore. at the AGM unless your dues are Twelve vendors. From kilts to current. -

Sooloos Collections: Advanced Guide

Sooloos Collections: Advanced Guide Sooloos Collectiions: Advanced Guide Contents Introduction ...........................................................................................................................................................3 Organising and Using a Sooloos Collection ...........................................................................................................4 Working with Sets ..................................................................................................................................................5 Organising through Naming ..................................................................................................................................7 Album Detail ....................................................................................................................................................... 11 Finding Content .................................................................................................................................................. 12 Explore ............................................................................................................................................................ 12 Search ............................................................................................................................................................. 14 Focus .............................................................................................................................................................. -

El Librofest Metropolitano 2016: Un Encuentro Con El Conocimiento

Vol. XXII • Núm. 39 • 06•06•2016 • ISSN1405-177X El Librofest Metropolitano 2016: un encuentro con el conocimiento Versión flip www.uam.mx/semanario/ UAM Comunicación www.facebook.com/UAMComunicacion En Portada Aviso a la comunidad universitaria Próxima sesión del Colegio Académico Con la participación de 60 editoriales y un vasto programa de actividades culturales se efectuó el 3er. Librofest Metropolitano 2016 de la UAM. Con fundamento en el artículo 42 del Regla- mento Interno de los Órganos Colegiados Si tienes algo Académicos, se informa que el Colegio Aca- démico llevará a cabo sus sesiones 397 y que contar 398, el 8 de junio próximo a partir de las 10:00 horas, en el segundo piso del Edificio o mostrar “H” de la Unidad Iztapalapa. compártelo con el Orden del día y documentación disponibles en: http://colegiados.uam.mx Transmisión: www.uam.mx/video/envivo/ [email protected] 5483 4000 Oficina Técnica del Colegio Académico Ext. 1523 Para más información sobre la UAM: Semanario de la UAM. Órgano informativo de la Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana. Unidad Azcapotzalco: Vol. XXII, Número 39, 6 de junio de 2016, es una publicación semanal editada Lic. Rosalinda Aldaz Vélez por la Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana. Prolongación Canal de Miramontes 3855, Jefa de la Oficina de Comunicación Col. Ex-Hacienda San Juan de Dios, Delegación Tlalpan, C.P. 14387, 5318 9519. [email protected] México, D.F.; teléfono 5483 4000, Ext. 1522. Rector General Unidad Cuajimalpa: Página electrónica de la revista: www.uam.mx/comunicacionsocial/semanario.html Lic. María Magdalena Báez Sánchez Dr. Salvador Vega y León dirección electrónica: [email protected] Coordinadora de Extensión Universitaria 5814 6560. -

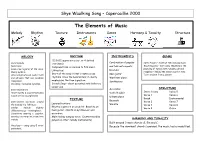

The Elements of Music

Skye Waulking Song – Capercaillie 2000 The Elements of Music Melody Rhythm Texture Instruments Genre Harmony & Tonality Structure MELODY RHYTHM INSTRUMENTS GENRE 12/8 (12 quavers in a bar, or 4 dotted Combination of popular Vocal melody: crotchets) Celtic Fusion – Scottish folk and pop music. Waulking song – work song. Waulking is the Pentatonic. Compound time is common to folk music. and folk instruments. Uses a low register of the voice. pounding of tweed cloth. Usually call and Lilting feel. Drum kit Mainly syllabic. response – helped the women work in time. Start of the song: hi-hat creates cross Alternates between Gaelic (call) Bass guitar Text is taken from a lament. and phrases that use vocables rhythms. Once the band enters it clearly Wurlitzer piano (response) emphasises the time signature. Synthesizer Vocables = nonsense syllables. Scotch Snap – short accented note before a longer one. STRUCTURE Instrumentalists: Accordion Short motifs & Countermelodies Violin (fiddle) Intro: 8 bars. Verse 5 Verse 1 Verse 6 based on the vocal phrases. Uileann pipes Break Instrumental TEXTURE Bouzouki Instruments improvise around Verse 2 Verse 7 Layered texture: the melody in a folk style. Whistle Verse 3 Verse 8 Rhythmic pattern on drum kit. Bass line on Similar melody slightly Verse 4 Outro bass guitar. Chords on synthesizer and different ways = heterophonic. Sometimes weaving a complex, accordion. weaving counterpoint around the Main melody sung by voice. Countermelodies HARMONY AND TONALITY melody. played on other melody instruments) Built around 3 main chords: G, Em and C. Vocal part = sung using E minor Because the dominant chord is avoided, the music has a modal feel.