Rye Money and Rye Loans During the Weimar Republic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uncertainty and Hyperinflation: European Inflation Dynamics After World War I

FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF SAN FRANCISCO WORKING PAPER SERIES Uncertainty and Hyperinflation: European Inflation Dynamics after World War I Jose A. Lopez Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Kris James Mitchener Santa Clara University CAGE, CEPR, CES-ifo & NBER June 2018 Working Paper 2018-06 https://www.frbsf.org/economic-research/publications/working-papers/2018/06/ Suggested citation: Lopez, Jose A., Kris James Mitchener. 2018. “Uncertainty and Hyperinflation: European Inflation Dynamics after World War I,” Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Working Paper 2018-06. https://doi.org/10.24148/wp2018-06 The views in this paper are solely the responsibility of the authors and should not be interpreted as reflecting the views of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco or the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. Uncertainty and Hyperinflation: European Inflation Dynamics after World War I Jose A. Lopez Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Kris James Mitchener Santa Clara University CAGE, CEPR, CES-ifo & NBER* May 9, 2018 ABSTRACT. Fiscal deficits, elevated debt-to-GDP ratios, and high inflation rates suggest hyperinflation could have potentially emerged in many European countries after World War I. We demonstrate that economic policy uncertainty was instrumental in pushing a subset of European countries into hyperinflation shortly after the end of the war. Germany, Austria, Poland, and Hungary (GAPH) suffered from frequent uncertainty shocks – and correspondingly high levels of uncertainty – caused by protracted political negotiations over reparations payments, the apportionment of the Austro-Hungarian debt, and border disputes. In contrast, other European countries exhibited lower levels of measured uncertainty between 1919 and 1925, allowing them more capacity with which to implement credible commitments to their fiscal and monetary policies. -

Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1891-1957, Record Group 85 New Orleans, Louisiana Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New Orleans, LA, 1910-1945

Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1891-1957, Record Group 85 New Orleans, Louisiana Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New Orleans, LA, 1910-1945. T939. 311 rolls. (~A complete list of rolls has been added.) Roll Volumes Dates 1 1-3 January-June, 1910 2 4-5 July-October, 1910 3 6-7 November, 1910-February, 1911 4 8-9 March-June, 1911 5 10-11 July-October, 1911 6 12-13 November, 1911-February, 1912 7 14-15 March-June, 1912 8 16-17 July-October, 1912 9 18-19 November, 1912-February, 1913 10 20-21 March-June, 1913 11 22-23 July-October, 1913 12 24-25 November, 1913-February, 1914 13 26 March-April, 1914 14 27 May-June, 1914 15 28-29 July-October, 1914 16 30-31 November, 1914-February, 1915 17 32 March-April, 1915 18 33 May-June, 1915 19 34-35 July-October, 1915 20 36-37 November, 1915-February, 1916 21 38-39 March-June, 1916 22 40-41 July-October, 1916 23 42-43 November, 1916-February, 1917 24 44 March-April, 1917 25 45 May-June, 1917 26 46 July-August, 1917 27 47 September-October, 1917 28 48 November-December, 1917 29 49-50 Jan. 1-Mar. 15, 1918 30 51-53 Mar. 16-Apr. 30, 1918 31 56-59 June 1-Aug. 15, 1918 32 60-64 Aug. 16-0ct. 31, 1918 33 65-69 Nov. 1', 1918-Jan. 15, 1919 34 70-73 Jan. 16-Mar. 31, 1919 35 74-77 April-May, 1919 36 78-79 June-July, 1919 37 80-81 August-September, 1919 38 82-83 October-November, 1919 39 84-85 December, 1919-January, 1920 40 86-87 February-March, 1920 41 88-89 April-May, 1920 42 90 June, 1920 43 91 July, 1920 44 92 August, 1920 45 93 September, 1920 46 94 October, 1920 47 95-96 November, 1920 48 97-98 December, 1920 49 99-100 Jan. -

JOHNSTOWN V. the NEGRO: SOUTHERN MIGRANTS and the EXODUS of 1923

JOHNSTOWN v. THE NEGRO: SOUTHERN MIGRANTS AND THE EXODUS OF 1923 BY RICHARD B. SHERMAN* ONE of the most significant demographic changes in American history was the vast migration of Southern Negroes to the North during and shortly after the First World War. Within a period of a few years hundreds of thousands of Negroes found opportunities in the North that heretofore had been denied to them. However, the migration also made clearer than ever before the national character of American racial problems. Particularly in the early stages, it meant that an economically and culturally oppressed minority was placed in sharp and unaccustomed contact with people in Northern communities who were unprepared for the change. This process provided a dramatic test of the devotion of Americans to their ideals of freedom and equality. In some areas there were heartening instances of successful adjustment. But there were also dismaying failures. An example of the latter was provided during the early 1920's by Johnstown, Pennsylvania, where community apathy and demagogic leadership resulted in misfortune for many of the newcomers. From 1915 through the 1920's the Negro's northward migration came in two main phases, and Johnstown was affected by both. The first phase reached a peak between 1916 and 1917, and then sharply declined for a few years. A second phase was under way by 1922 and culminated the next year. Prompted by economic and social oppression in the South, and lured by the opportunities presented by labor shortages in the North, vast numbers of Negroes moved off the land, to the cities, and into the North.] *Dr. -

The Egyptian, October 16, 1923

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC October 1923 Daily Egyptian 1923 10-16-1923 The gE yptian, October 16, 1923 Egyptian Staff Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/de_October1923 Volume 4, Issue 3 Recommended Citation Egyptian Staff, "The gE yptian, October 16, 1923" (1923). October 1923. Paper 3. http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/de_October1923/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Daily Egyptian 1923 at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in October 1923 by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Read by Four Thousand Students, Faculty and Friends of the 'School Volume IV Carbondale, Illinois, October 16. 1923 Number J f~ ..... : wIth 'hard work. He Md'the advantage ot the public s~hoor" 01 hi~' day and attended the "Oak Grove" school. He also at· tended ui'e Higbland schOOl whete he prepared fOr oollege. I~ 1864 he and bls brother" George, entered McKenliree Chllege aM' roomeli In' tlIe hlCime of Professor ,neneen, tbe father of Ex!.Governar Charles S. Deneen. Yonng Deneen and youug Parkinson were play:mate friends anil the youthful ties which were formed In those days we~e strengthened as the two youth1l grew' olde~ until tbey rlpeneli Into a fMendehip whidb bas lasteh even unto death. Dr. Parkinson graduatea from McKeddree College while Dr. Robert Allyn was 'president of the 'ooilege, Here I'.notllElr acquaintance grew into respect and love and warm affection. FOllowIng graduation Dr. PiI!rkiDsoD began teaching, beginning at Carmi He later became a member of tbe faculty of Jennings Seminary, Aurora, IIlfllols. -

Official Gazette Colony and Protectorate of Kenya

THE OFFICIAL GAZETTE OF THE COLONY AND PROTECTORATE OF KENYA. Published under the Authority of His Excellency the Governor of the Colony and Protectorate of Kenya. [Vol. XXVL—No. 922] NATROBI, January 2, 1924. [Prices 50 Cenrs] Registered as a Newspaper ai the G. P. 0. Published every Wednesday. TABLE OF CONTENTS. PAGE Govt. Notice No, 1—Appointments ves vee ves .. wes vee 2 » 0 ’ 2—A. Bill intituled an Ordinance to Amend the Legislative Conncil Ordinance, 1919 ce Le . Lee . BA4 ” ” ” 3—A Bill intituled an Ordinance to Amend the Native Liquor Ordinance, 1921 wee vee a Lee vee 4 Proclamation No, 1—The Kenya and Uganda (Currency) Order, 1921... vee bee 4 Proclamation No. : 2—The Diseases of Animals Ordinance, 1906 . 5 Govt. Notice No. 4——-Public Health Ordinance, 1921—Notiee ... a vee wes 5 »»» 5-6—The Native Authority Ordinance, 1912—Appointments of Oficial Headmen bee Lee Le ves vee vee 3 Gen. Notices Nos. 1-11—Miscellaneeus Notices ... ve Lee i _ we 5H 2 THE OFFICIAL GAZETTE January 2, 1924. Government Notice No. 1. APPOINTMENTS. W. McHarpy, 0.B.E., M.A., to be Superintendent (Admin- 5. 18816 /930. istrative), Uganda Railway, with effect from Ist January, Guorce Eenest Scarrercoop, to be Accountant, Medical 1924. Department, with effect from the 24th July, 1923. _ A. G. Hicerns, to be Secretary to the Railway Council and CG. M. Bunsury, to be Senior District Engineer, Uganda Private Secretary to the General Manager, Uganda Rail- Railway, with effect from Ist January, 1924. way, with effect from Ist January, 1924. -

A Social Analysis of KPD Supporters: the Hamburg Insurrectionaries Of

LARRY PETERSON A SOCIAL ANALYSIS OF KPD SUPPORTERS: THE HAMBURG INSURRECTION- ARIES OF OCTOBER 1923* Although much has been written about the history of the German Communist Party, little is known about who actually belonged to it or supported it. Yet knowledge of the social composition of German Communism is an important, in many ways crucial, factor in assessing the role of the KPD in the development of the German workers' movement during the Weimar Republic. Aside from a census of party members conducted by the national leadership in 1927, and voting returns in elections, there are no national sources on which to base an analysis of the social structure of the Communist movement in Germany. Local and regional sources, though sporadically preserved and until now little ex- ploited, offer an alternative way to determine the social bases of German Communism. This article contributes to the history of the KPD by attempting to analyze one source about support for German Communism in a major industrial city. In October 1923 the KPD staged an insurrection in Hamburg, resulting in the arrest and conviction of over 800 persons. A social analysis of these known insurrectionaries can indicate some of the sources of support for the KPD and suggest some of the ways in which the KPD fit into the history of the German working class and workers' move- ment. The Hamburg insurrection of October 1923 was itself a political mis- understanding. In early October, at the height of the inflation, the KPD entered coalition governments with the Social Democratic Party in Saxony and Thuringia. -

Germany 1919-1941 U.S

U.S. MILITARY INTELLIGENCE REPORTS : GERMANY 1919-1941 U.S. MILITARY INTELLIGENCE REPORTS: GERMANY, 1919-1941 Edited by Dale Reynolds Guide Compiled by Robert Lester A Microfilm Project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA, INC. 44 North Market Street • Frederick, MD 21701 Copyright© 1983 by University Publications of America, Inc. All rights reserved. ISBN 0-89093^26-6. Note on Sources The Documents in this Collection are from the National Archives and Record Service, Washington, D.C., Record Group #165. Mil- itary Intelligence Division Files: Germany. TABLE OF CONTENTS Red Index 1 Reel I 1 Reel II 6 Reel III 10 Reel IV 15 Reel V 18 Reel VI 22 Reel VII 25 Reel VIII 29 Reel IX 31 Reel X 33 Reel XI 33 Reel XII 34 Reel XIII 35 Reel XIV 38 Reel XV 39 Reel XVI 41 Reel XVII 43 Reel XVIII 45 Reel XIX 47 Reel XX 49 Reel XXI 52 Reel XXII 54 Reel XXIII 56 Reel XXIV 58 Reel XXV 61 Reel XXVI 63 Reel XXVII 65 Reel XXVIII 68 Subject Index 71 Dates to Remember February 3,1917 Severance of U.S. Diplomatic Relations with Germany; Declara- tion of War November 11,1918 Armistice December 1, 1918 U.S. Troops of the 3rd Army cross the Rhine and Occupy the Rhine Province July 2,1919 Departure of the U.S. 3rd Army; the U.S. Army of the Rhine Occupies Coblenz in the Rhine Province December 10, 1921 Presentation of Credentials of the U.S. Charge d'Affaires in Berlin April 22, 1922 Withdrawal of U.S. -

The Ends of Four Big Inflations

This PDF is a selection from an out-of-print volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: Inflation: Causes and Effects Volume Author/Editor: Robert E. Hall Volume Publisher: University of Chicago Press Volume ISBN: 0-226-31323-9 Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/hall82-1 Publication Date: 1982 Chapter Title: The Ends of Four Big Inflations Chapter Author: Thomas J. Sargent Chapter URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c11452 Chapter pages in book: (p. 41 - 98) The Ends of Four Big Inflations Thomas J. Sargent 2.1 Introduction Since the middle 1960s, many Western economies have experienced persistent and growing rates of inflation. Some prominent economists and statesmen have become convinced that this inflation has a stubborn, self-sustaining momentum and that either it simply is not susceptible to cure by conventional measures of monetary and fiscal restraint or, in terms of the consequent widespread and sustained unemployment, the cost of eradicating inflation by monetary and fiscal measures would be prohibitively high. It is often claimed that there is an underlying rate of inflation which responds slowly, if at all, to restrictive monetary and fiscal measures.1 Evidently, this underlying rate of inflation is the rate of inflation that firms and workers have come to expect will prevail in the future. There is momentum in this process because firms and workers supposedly form their expectations by extrapolating past rates of inflation into the future. If this is true, the years from the middle 1960s to the early 1980s have left firms and workers with a legacy of high expected rates of inflation which promise to respond only slowly, if at all, to restrictive monetary and fiscal policy actions. -

The Berlin Stock Exchange in the “Great Disorder” Stephanie Collet (Deutsche Bundesbank) and Caroline Fohlin (Emory University and CEPR London) Plan for the Talk

The Berlin Stock Exchange in the “Great Disorder” Stephanie Collet (Deutsche Bundesbank) and Caroline Fohlin (Emory University and CEPR London) Plan for the talk • Background on “The Great Disorder” • Microstructure of the Berlin Stock Exchange • Data & Methods • Results: 1. Market Activity 2. Order Imbalance 3. Direction of Trade—excess supply v. demand 4. Volatility of returns 5. Market illiquidity—Roll measure “The Great Disorder” Median Share Price and C&F100, 1921-30 (Daily) 1000000000.00 From the end of World War I to the Great Depression 100000000.00 • Political upheaval: 10000000.00 • Abdication of Kaiser Wilhelm II Median C&F100 1000000.00 • Founding of the Weimar Republic • Rise of the Nazi party 100000.00 • Economic upheaval: • Massive war debt and reparations 10000.00 Percent of par value of par Percent • Loss of productive capacity (and land) 1000.00 • Monetary upheaval: • Hyperinflation and its end 100.00 • Reichsbank policy regime changes 10.00 • Financial upheaval: • Boom in corporate foundations 1.00 • 1927 stock market “bubble” and collapse (Black Friday, 13. May 1927) Date Early 20’s Run-up to Hyperinflation Median Share Price in the Early Stages of Inflation, 1921-22 (Daily) 1600.00 1400.00 “London Assassination of 1200.00 Ultimatum” on foreign minister, reparations Walther Rathenau 1000.00 800.00 reparations set at 132 billion 600.00 gold marks Percent of par value parof Percent 400.00 Germany demands 200.00 Median C&F100 moratorium on reparation payments 0.00 Date Political Event Economic/Reparations Event Financial/Monetary Event The Hyperinflation Median Share Price and C&F100 During the Peak Hyperinflation, Median October 1922-December 1923 (Daily) C&F100 1000000000.00 Hilter's 100000000.00 beer hall putsch, 10000000.00 Occupation Munich of Ruhr 1000000.00 15. -

S Ubject L Ist N O. 44 of DOCUMENTS DISTRIBUTED to the MEMBERS of the COUNCIL DURING DECEMBER 1924

[DISTRIBUTED ,, e a g u e o f a t i o n s C. 5. MEMBERS OFT0TllE THE COUNCIL ] L N 1925- G en ev a , January 4 t h , 1925. S ubject L ist N o. 44 OF DOCUMENTS DISTRIBUTED TO THE MEMBERS OF THE COUNCIL DURING DECEMBER 1924. (Prepared by the Distribution Branch.) Armaments, Reduction 0! Arms, Private manufacture of and traffic in Convention concluded September 10, 1919 at St. Germain-en-Laye for the control of traffic in arms Convention to supersede Conference, May 1925, Geneva, to prepare A Report dated December 1924 by Czechoslovak Representative (M. Benes) and resolution adopted December 8, 1924 by 32nd Council Session, fixing May 4, 1925 as date for Admissions to League C. 801. 1924. IX Germany Letter dated December r 2, 1924 from German Government (M. Stresemann) forwarding copy Text (draft) subm itted July 1924 by Temporary of its memorandum to the Governments repre Mixed Commission, of sented on the Council with a view to the elucida Letter dated October 9, 1924 from Secretary- tion of certain problems connected with Germany's General to States Members and Non- co-operation with League, announcing its satis Members of the League quoting relative faction with the replies received, except with Assembly resolution, forwarding Tempo regard to Article 16 of Covenant, and submitting rary Mixed Commission's report (A. 16. detailed statement of its apprehensions with 1924) containing above-mentioned draft and regard to this article minutes of discussion of its Article 9, and the report of 3rd Commission to Assembly C. -

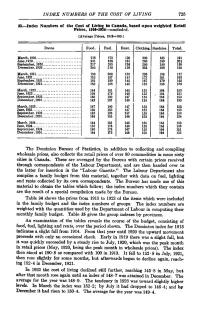

INDEX NUMBERS of the COST of LIVING 725 33.—Index Numbers of the Cost of Living in Canada, Based Upon Weighted Retail Prices

INDEX NUMBERS OF THE COST OF LIVING 725 33.—Index Numbers of the Cost of Living in Canada, based upon weighted Retail Prices, 1910-1934—concluded. (Average Prices, 1913=100.) Dates. Food. Fuel. Rent. Clothing. Sundries. Total. March, 1920 218 173 120 260 185 191 June,1920 231 186 133 260 190 201 September, 1920 217 285 136 260 190 199 December, 1920. 202 218 139 235 190 192 March, 1921 180 208 139 195 188 177 June,1921 152 197 143 173 181 163 September, 1921 161 189 145 167 170 162 December, 1921. 150 186 145 158 166 156 March, 1922 144 181 145 155 164 153 June, 1922 139 179 146 155 . 164 151 September, 1922. 140 190 147 155 164 153 December, 1922. 142 187 146 155 164 153 March, 1923 147 190 147 155 164 155 June,1923 139 182 147 155 164 152 September, 1923. 142 183 147 155 164 153 December, 1923. 146 185 146 155 164 154 March, 1924 144 181 146 155 164 153 June,1924 133 176 146 155 164 149 September, 1924. 140 176 147 155 164 151 December, 1924. 144 175 146 155 164 152 The Dominion Bureau of Statistics, in addition to collecting and compiling wholesale prices, also collects the retail prices of over 80 commodities in some sixty cities in Canada. These are averaged by the Bureau with certain prices received through correspondents of the Labour Department, and are then handed over to the latter for insertion in the "Labour Gazette." The Labour Department also compiles a family budget from this material, together with data on fuel, lighting and rents collected by its own correspondents. -

Economic Crises of Weimar Republic, 1923 & 1929 Block

LHS World History Name: Reading #1 Date: Economic Crises of Weimar Republic, 1923 & 1929 Block: Two economic events shattered the average German’s faith in the Weimar Republic. The first event was the hyperinflation crisis of 1923. The second event was the Great Depression that began in 1929. When in January 1923, France and Belgium occupied the Ruhr in response to Weimar’s announced policy of “non cooperation” Berlin countered by ordering passive resistance. In doing so, they paid the workers of Germany to not work. These became known as “resistance wages.” To pay the resistance wages, the presses began to print astronomical amounts of money. By December 1923, Germany was in the grips of a hyperinflation crisis unprecedented in the annals of western civilization. $1.00 cost 4 million RM (Reichmark). A woman might order a cup of coffee for 5000 RM and get a bill for 8000 RM an hour later. By December of 1923 90% of average family expenditure was going towards food. A massive crime wave swept the country. Child prostitution was off the charts as families sold their children for food, and precious metals disappeared off th of the streets. Germany collapsed into a full barter economy, reminiscent of 9 century Europe. Full economic collapse stared the government in the face. Though for years it has been claimed by historians that the hyperinflation crisis wiped out the German middle class, this was simply not the case. The inflation did not destroy the economic position of the middle class. Some like mortgage holders, debtors or businessmen who bought on installment payments gained; others such as investors or bondholders, lost.