Economic Crises of Weimar Republic, 1923 & 1929 Block

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uncertainty and Hyperinflation: European Inflation Dynamics After World War I

FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF SAN FRANCISCO WORKING PAPER SERIES Uncertainty and Hyperinflation: European Inflation Dynamics after World War I Jose A. Lopez Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Kris James Mitchener Santa Clara University CAGE, CEPR, CES-ifo & NBER June 2018 Working Paper 2018-06 https://www.frbsf.org/economic-research/publications/working-papers/2018/06/ Suggested citation: Lopez, Jose A., Kris James Mitchener. 2018. “Uncertainty and Hyperinflation: European Inflation Dynamics after World War I,” Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Working Paper 2018-06. https://doi.org/10.24148/wp2018-06 The views in this paper are solely the responsibility of the authors and should not be interpreted as reflecting the views of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco or the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. Uncertainty and Hyperinflation: European Inflation Dynamics after World War I Jose A. Lopez Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Kris James Mitchener Santa Clara University CAGE, CEPR, CES-ifo & NBER* May 9, 2018 ABSTRACT. Fiscal deficits, elevated debt-to-GDP ratios, and high inflation rates suggest hyperinflation could have potentially emerged in many European countries after World War I. We demonstrate that economic policy uncertainty was instrumental in pushing a subset of European countries into hyperinflation shortly after the end of the war. Germany, Austria, Poland, and Hungary (GAPH) suffered from frequent uncertainty shocks – and correspondingly high levels of uncertainty – caused by protracted political negotiations over reparations payments, the apportionment of the Austro-Hungarian debt, and border disputes. In contrast, other European countries exhibited lower levels of measured uncertainty between 1919 and 1925, allowing them more capacity with which to implement credible commitments to their fiscal and monetary policies. -

Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1891-1957, Record Group 85 New Orleans, Louisiana Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New Orleans, LA, 1910-1945

Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1891-1957, Record Group 85 New Orleans, Louisiana Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New Orleans, LA, 1910-1945. T939. 311 rolls. (~A complete list of rolls has been added.) Roll Volumes Dates 1 1-3 January-June, 1910 2 4-5 July-October, 1910 3 6-7 November, 1910-February, 1911 4 8-9 March-June, 1911 5 10-11 July-October, 1911 6 12-13 November, 1911-February, 1912 7 14-15 March-June, 1912 8 16-17 July-October, 1912 9 18-19 November, 1912-February, 1913 10 20-21 March-June, 1913 11 22-23 July-October, 1913 12 24-25 November, 1913-February, 1914 13 26 March-April, 1914 14 27 May-June, 1914 15 28-29 July-October, 1914 16 30-31 November, 1914-February, 1915 17 32 March-April, 1915 18 33 May-June, 1915 19 34-35 July-October, 1915 20 36-37 November, 1915-February, 1916 21 38-39 March-June, 1916 22 40-41 July-October, 1916 23 42-43 November, 1916-February, 1917 24 44 March-April, 1917 25 45 May-June, 1917 26 46 July-August, 1917 27 47 September-October, 1917 28 48 November-December, 1917 29 49-50 Jan. 1-Mar. 15, 1918 30 51-53 Mar. 16-Apr. 30, 1918 31 56-59 June 1-Aug. 15, 1918 32 60-64 Aug. 16-0ct. 31, 1918 33 65-69 Nov. 1', 1918-Jan. 15, 1919 34 70-73 Jan. 16-Mar. 31, 1919 35 74-77 April-May, 1919 36 78-79 June-July, 1919 37 80-81 August-September, 1919 38 82-83 October-November, 1919 39 84-85 December, 1919-January, 1920 40 86-87 February-March, 1920 41 88-89 April-May, 1920 42 90 June, 1920 43 91 July, 1920 44 92 August, 1920 45 93 September, 1920 46 94 October, 1920 47 95-96 November, 1920 48 97-98 December, 1920 49 99-100 Jan. -

Official Gazette Colony and Protectorate of Kenya

THE OFFICIAL GAZETTE OF THE COLONY AND PROTECTORATE OF KENYA. Published under the Authority of His Excellency the Governor of the Colony and Protectorate of Kenya. [Vol. XXVL—No. 922] NATROBI, January 2, 1924. [Prices 50 Cenrs] Registered as a Newspaper ai the G. P. 0. Published every Wednesday. TABLE OF CONTENTS. PAGE Govt. Notice No, 1—Appointments ves vee ves .. wes vee 2 » 0 ’ 2—A. Bill intituled an Ordinance to Amend the Legislative Conncil Ordinance, 1919 ce Le . Lee . BA4 ” ” ” 3—A Bill intituled an Ordinance to Amend the Native Liquor Ordinance, 1921 wee vee a Lee vee 4 Proclamation No, 1—The Kenya and Uganda (Currency) Order, 1921... vee bee 4 Proclamation No. : 2—The Diseases of Animals Ordinance, 1906 . 5 Govt. Notice No. 4——-Public Health Ordinance, 1921—Notiee ... a vee wes 5 »»» 5-6—The Native Authority Ordinance, 1912—Appointments of Oficial Headmen bee Lee Le ves vee vee 3 Gen. Notices Nos. 1-11—Miscellaneeus Notices ... ve Lee i _ we 5H 2 THE OFFICIAL GAZETTE January 2, 1924. Government Notice No. 1. APPOINTMENTS. W. McHarpy, 0.B.E., M.A., to be Superintendent (Admin- 5. 18816 /930. istrative), Uganda Railway, with effect from Ist January, Guorce Eenest Scarrercoop, to be Accountant, Medical 1924. Department, with effect from the 24th July, 1923. _ A. G. Hicerns, to be Secretary to the Railway Council and CG. M. Bunsury, to be Senior District Engineer, Uganda Private Secretary to the General Manager, Uganda Rail- Railway, with effect from Ist January, 1924. way, with effect from Ist January, 1924. -

The Foreign Service Journal, December 1924

tHti AMERICAN FOREIGN SERVICE JOURNAL (Contributed by the Under Secretary of State, Hon. J. C. Grew) ON THE SCHEIDEGG, SWITZERLAND, 1924 Vol. I DECEMBER, 1924 No. 3 FEDERAL-AMERICAN NATIONAL BANK NOW IN COURSE OF CONSTRUCTION IN WASHINGTON, D. C. W. T. GALLIHER, Chairman of the Board JOHN POOLE, President RESOURCES OVER $13,000,000.00 FOREIGN S JOURNAL PUBLISHED MONTHLY BY THE AMERICAN POREIGN SERVICE ASSOCIATION VOL. I. No. 3 WASHINGTON, D. C. DECEMBER, 1924 The Presidential Election By GERHARD GADE 1916 1920 1924 N November 4 the people of the United State Rep. Dem. Rep. Dem. Rep. Dem. States elected Calvin Coolidge President Maryland 8 8 8 by a popular vote estimated at about Massachusetts . .. .. 18 18 18 18.000,000—2,000,000 more votes than President Michigan .. 15 15 15 Harding received in 1920, although the latter Minnesota .. 12 12 12 Mississippi 10 16 10 polled 22 more electoral votes than his successor. Missouri 18 18 is The popular vote in the last three elections was Montana 4 4 4 as follows: Nebraska 8 8 8 Nevada 3 3 3 1916 Woodrow Wilson 9,129,606 New Hampshire .. 4 4 4 Charles E. Hughes 8,538,221 New Jersey .. ii 14 14 1920 Warren G. Harding 16,152,200 New Mexico 3 3 3 James M. Cox 9,147,353 New York .. 45 45 45 1924 Calvin Coolidge 18,000,000* North Carolina . 12 ii ii John W. Davis 9,000,000* North Dakota .... S 5 5 Robert M. La Follette 4,000,000* Ohio 24 24 24 Oklahoma 10 10 10 * Estimated. -

Germany, Reparation Commission)

REPORTS OF INTERNATIONAL ARBITRAL AWARDS RECUEIL DES SENTENCES ARBITRALES Interpretation of London Agreement of August 9, 1924 (Germany, Reparation Commission) 24 March 1926, 29 January 1927, 29 May 1928 VOLUME II pp. 873-899 NATIONS UNIES - UNITED NATIONS Copyright (c) 2006 XXI a. INTERPRETATION OF LONDON "AGREEMENT OF AUGUST 9, 1924 *. PARTIES: Germany and Reparation Commission. SPECIAL AGREEMENT: Terms of submission contained in letter signed by Parties in Paris on August 28, 1925, in conformity with London Agree- ment of August 9, 1924. ARBITRATORS: Walter P. Cook (U.S.A.), President, Marc. Wallen- berg (Sweden), A. G. Kroller (Netherlands), Charles Rist (France), A. Mendelssohn Bartholdy (Germany). AWARD: The Hague, March 24, 1926. Social insurance funds in Alsace-Lorraine.—Social insurance funds in Upper Silesia.—Intention of a provision as a principle of interpretation.— Experts' report and countries not having accepted the report.—Baden Agreement of March 3, 1920.—Restitution in specie.—Spirit of a treaty.— Supply of coal to the S.S. Jupiter.—Transaction of private character. For bibliography, index and tables, see Volume III. 875 Special Agreement. AGREEMENT BETWEEN THE REPARATION COMMISSION AND THE GERMAN GOVERNMENT. Signed at London. August 9th, 1924. Ill (b) Any dispute which may arise between the Reparation Commission and the German Government with regard to the interpretation either of the present agreement and its schedules or of the experts' plan or of the •German legislation enacted in execution of that plan, shall be submitted to arbitration in accordance with the methods to be fixed and subject to the conditions to be determined by the London conference for questions of the interpretation of the experts' Dlan. -

The Ends of Four Big Inflations

This PDF is a selection from an out-of-print volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: Inflation: Causes and Effects Volume Author/Editor: Robert E. Hall Volume Publisher: University of Chicago Press Volume ISBN: 0-226-31323-9 Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/hall82-1 Publication Date: 1982 Chapter Title: The Ends of Four Big Inflations Chapter Author: Thomas J. Sargent Chapter URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c11452 Chapter pages in book: (p. 41 - 98) The Ends of Four Big Inflations Thomas J. Sargent 2.1 Introduction Since the middle 1960s, many Western economies have experienced persistent and growing rates of inflation. Some prominent economists and statesmen have become convinced that this inflation has a stubborn, self-sustaining momentum and that either it simply is not susceptible to cure by conventional measures of monetary and fiscal restraint or, in terms of the consequent widespread and sustained unemployment, the cost of eradicating inflation by monetary and fiscal measures would be prohibitively high. It is often claimed that there is an underlying rate of inflation which responds slowly, if at all, to restrictive monetary and fiscal measures.1 Evidently, this underlying rate of inflation is the rate of inflation that firms and workers have come to expect will prevail in the future. There is momentum in this process because firms and workers supposedly form their expectations by extrapolating past rates of inflation into the future. If this is true, the years from the middle 1960s to the early 1980s have left firms and workers with a legacy of high expected rates of inflation which promise to respond only slowly, if at all, to restrictive monetary and fiscal policy actions. -

Yesterday's News: Media Framing of Hitler's Early Years, 1923-1924

92 — The Elon Journal of Undergraduate Research in Communications, Vol. 6, No. 1 • Spring 2015 Yesterday’s News: Media Framing of Hitler’s Early Years, 1923-1924 Katherine Blunt Journalism and History Elon University Abstract This research used media framing theory to assess newspaper coverage of Hitler published in The New York Times, The Christian Science Monitor, and The Washington Post between 1923 and 1924. An analysis of about 200 articles revealed “credible” and “non-credible” frames relating to his political influence. Prior to Hitler’s trial for treason in 1924, the credible frame was slightly more prevalent. Following his subsequent conviction, the non-credible frame dominated coverage, with reports often presenting Hitler’s failure to over- throw the Bavarian government as evidence of his lack of political skill. This research provides insight into the way American media cover foreign leaders before and after a tipping point—one or more events that call into question their political efficacy. I. Introduction The resentment, suspicion, and chaos that defined global politics during the Great arW continued into the 1920s. Germany plunged into a state of political and economic turmoil following the ratification of the punitive Treaty of Versailles, and the Allies watched with trepidation as it struggled to make reparations pay- ments. The bill — equivalent to 33 billion dollars then and more than 400 billion dollars today — grew increas- ingly daunting as the value of the mark fell from 400 to the dollar in 1922 to 7,000 to the dollar at the start of 1923, when Bavaria witnessed the improbable rise of an Austrian-born artist-turned-politician who channeled German outrage into a nationalistic, anti-Semitic movement that came to be known as the Nazi Party.1 Ameri- can media outlets, intent on documenting the chaotic state of post-war Europe, took notice of Adolf Hitler as he attracted a following and, through their coverage, essentially introduced him to the American public. -

The Berlin Stock Exchange in the “Great Disorder” Stephanie Collet (Deutsche Bundesbank) and Caroline Fohlin (Emory University and CEPR London) Plan for the Talk

The Berlin Stock Exchange in the “Great Disorder” Stephanie Collet (Deutsche Bundesbank) and Caroline Fohlin (Emory University and CEPR London) Plan for the talk • Background on “The Great Disorder” • Microstructure of the Berlin Stock Exchange • Data & Methods • Results: 1. Market Activity 2. Order Imbalance 3. Direction of Trade—excess supply v. demand 4. Volatility of returns 5. Market illiquidity—Roll measure “The Great Disorder” Median Share Price and C&F100, 1921-30 (Daily) 1000000000.00 From the end of World War I to the Great Depression 100000000.00 • Political upheaval: 10000000.00 • Abdication of Kaiser Wilhelm II Median C&F100 1000000.00 • Founding of the Weimar Republic • Rise of the Nazi party 100000.00 • Economic upheaval: • Massive war debt and reparations 10000.00 Percent of par value of par Percent • Loss of productive capacity (and land) 1000.00 • Monetary upheaval: • Hyperinflation and its end 100.00 • Reichsbank policy regime changes 10.00 • Financial upheaval: • Boom in corporate foundations 1.00 • 1927 stock market “bubble” and collapse (Black Friday, 13. May 1927) Date Early 20’s Run-up to Hyperinflation Median Share Price in the Early Stages of Inflation, 1921-22 (Daily) 1600.00 1400.00 “London Assassination of 1200.00 Ultimatum” on foreign minister, reparations Walther Rathenau 1000.00 800.00 reparations set at 132 billion 600.00 gold marks Percent of par value parof Percent 400.00 Germany demands 200.00 Median C&F100 moratorium on reparation payments 0.00 Date Political Event Economic/Reparations Event Financial/Monetary Event The Hyperinflation Median Share Price and C&F100 During the Peak Hyperinflation, Median October 1922-December 1923 (Daily) C&F100 1000000000.00 Hilter's 100000000.00 beer hall putsch, 10000000.00 Occupation Munich of Ruhr 1000000.00 15. -

S Ubject L Ist N O. 44 of DOCUMENTS DISTRIBUTED to the MEMBERS of the COUNCIL DURING DECEMBER 1924

[DISTRIBUTED ,, e a g u e o f a t i o n s C. 5. MEMBERS OFT0TllE THE COUNCIL ] L N 1925- G en ev a , January 4 t h , 1925. S ubject L ist N o. 44 OF DOCUMENTS DISTRIBUTED TO THE MEMBERS OF THE COUNCIL DURING DECEMBER 1924. (Prepared by the Distribution Branch.) Armaments, Reduction 0! Arms, Private manufacture of and traffic in Convention concluded September 10, 1919 at St. Germain-en-Laye for the control of traffic in arms Convention to supersede Conference, May 1925, Geneva, to prepare A Report dated December 1924 by Czechoslovak Representative (M. Benes) and resolution adopted December 8, 1924 by 32nd Council Session, fixing May 4, 1925 as date for Admissions to League C. 801. 1924. IX Germany Letter dated December r 2, 1924 from German Government (M. Stresemann) forwarding copy Text (draft) subm itted July 1924 by Temporary of its memorandum to the Governments repre Mixed Commission, of sented on the Council with a view to the elucida Letter dated October 9, 1924 from Secretary- tion of certain problems connected with Germany's General to States Members and Non- co-operation with League, announcing its satis Members of the League quoting relative faction with the replies received, except with Assembly resolution, forwarding Tempo regard to Article 16 of Covenant, and submitting rary Mixed Commission's report (A. 16. detailed statement of its apprehensions with 1924) containing above-mentioned draft and regard to this article minutes of discussion of its Article 9, and the report of 3rd Commission to Assembly C. -

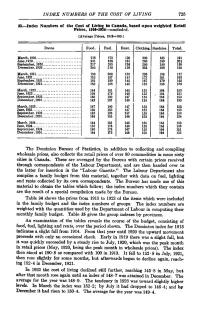

INDEX NUMBERS of the COST of LIVING 725 33.—Index Numbers of the Cost of Living in Canada, Based Upon Weighted Retail Prices

INDEX NUMBERS OF THE COST OF LIVING 725 33.—Index Numbers of the Cost of Living in Canada, based upon weighted Retail Prices, 1910-1934—concluded. (Average Prices, 1913=100.) Dates. Food. Fuel. Rent. Clothing. Sundries. Total. March, 1920 218 173 120 260 185 191 June,1920 231 186 133 260 190 201 September, 1920 217 285 136 260 190 199 December, 1920. 202 218 139 235 190 192 March, 1921 180 208 139 195 188 177 June,1921 152 197 143 173 181 163 September, 1921 161 189 145 167 170 162 December, 1921. 150 186 145 158 166 156 March, 1922 144 181 145 155 164 153 June, 1922 139 179 146 155 . 164 151 September, 1922. 140 190 147 155 164 153 December, 1922. 142 187 146 155 164 153 March, 1923 147 190 147 155 164 155 June,1923 139 182 147 155 164 152 September, 1923. 142 183 147 155 164 153 December, 1923. 146 185 146 155 164 154 March, 1924 144 181 146 155 164 153 June,1924 133 176 146 155 164 149 September, 1924. 140 176 147 155 164 151 December, 1924. 144 175 146 155 164 152 The Dominion Bureau of Statistics, in addition to collecting and compiling wholesale prices, also collects the retail prices of over 80 commodities in some sixty cities in Canada. These are averaged by the Bureau with certain prices received through correspondents of the Labour Department, and are then handed over to the latter for insertion in the "Labour Gazette." The Labour Department also compiles a family budget from this material, together with data on fuel, lighting and rents collected by its own correspondents. -

Month Calendar 1923 & Holidays 1923

January 1923 Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday 1 2 3 4 5 6 1 New Year's Day 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 2 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 3 Martin Luther King Day 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 4 28 29 30 31 5 January 1923 Calendar February 1923 Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday 1 2 3 5 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 6 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 7 Lincoln's Birthday Mardi Gras Carnival Valentine's Day 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 8 Presidents Day and Washington's Birthday 25 26 27 28 9 February 1923 Calendar March 1923 Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday 1 2 3 9 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 11 Daylight Saving St. Patrick's Day 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 12 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 13 Good Friday March 1923 Calendar April 1923 Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 14 Easter April Fool's Day Easter Monday 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 16 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 17 29 30 18 April 1923 Calendar May 1923 Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday 1 2 3 4 5 18 Cinco de Mayo 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 19 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Mother's Day Armed Forces Day 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 21 Pentecost Pentecost Monday 27 28 29 30 31 22 Memorial Day May 1923 Calendar June 1923 Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday 1 2 22 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 23 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 24 Flag Day 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 25 Father's Day 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 26 June 1923 Calendar July 1923 Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 27 Independence Day 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 28 15 16 17 18 19 -

Elections in the Weimar Republic the Elections to the Constituent National

HISTORICAL EXHIBITION PRESENTED BY THE GERMAN BUNDESTAG ____________________________________________________________________________________________________ Elections in the Weimar Republic The elections to the constituent National Assembly on 19 January 1919 were the first free and democratic national elections after the fall of the monarchy. For the first time, women had the right to vote and to stand for election. The MSPD and the Centre Party, together with the German Democratic Party, which belonged to the Liberal Left, won an absolute majority of seats in the Reichstag; these three parties formed the government known as the Weimar Coalition under the chancellorship of Philipp Scheidemann of the SPD. The left-wing Socialist USPD, on the other hand, which had campaigned for sweeping collectivisation measures and radical economic changes, derived no benefit from the unrest that had persisted since the start of the November revolution and was well beaten by the MSPD and the other mainstream parties. On 6 June 1920, the first Reichstag of the Weimar democracy was elected. The governing Weimar Coalition suffered heavy losses at the polls, losing 124 seats and thus its parliamentary majority, and had to surrender the reins of government. The slightly weakened Centre Party, whose vote was down by 2.3 percentage points, the decimated German Democratic Party, whose vote slumped by 10.3 percentage points, and the rejuvenated German People’s Party (DVP) of the Liberal Right, whose share of the vote increased by 9.5 percentage points, formed a minority government under the Centrist Konstantin Fehrenbach, a government tolerated by the severely weakened MSPD, which had seen its electoral support plummet by 16.2 percentage points.