Mixed Residential Communities in Northern Ireland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Open Space, Sport and Outdoor Recreation

POP016 Belfast LOCAL DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2020-2035 Open Space, Sport and Outdoor Recreation Topic Paper December 2016 Executive Summary Context Good quality open space makes our city an attractive and healthier place to live. Planning Policy 8 ‘Open Space, Sport and Recreation (PPS 8) defines open space as “all open space of public value, including not just land, but also inland bodies of water such as rivers, canals, lakes and reservoirs which offer important opportunities for sport and outdoor recreation and can also act as a visual amenity.” The typology of open space of public value ranges from parks and gardens to outdoor sports facilities, play parks, greenways, urban green spaces, community gardens and cemeteries. Open space can perform a multitude of functions, for example well-appointed open spaces can attract investment in cities which have balanced urban development with green infrastructure. The variety in the urban scene can have positive impacts on the landscape as well as providing good places to work, live and visit. These high urban quality spaces can support regeneration, improve quality of life for communities as well as promote health and wellbeing. Open space has a strategic function by helping to define an area, create a sense of place as well as create linkages between Cities and its rural hinterlands. Sensible, strategic land use planning can balance both the environmental function of open space to encourage biodiversity and the maintenance of ecosystems but can also deliver outdoor recreational needs of communities’ -

Helens Tower Sleeps 2 - Clandeboye Estate, Bangor, Co Down

Helens Tower Sleeps 2 - Clandeboye Estate, Bangor, Co Down. Situation: Presentation: Helen's Tower perched high above the rolling hills of Co Down, is an enchanting three storey stone tower nestled deep in the woods of the Clandeboye Estate. Standing on top of the world with panoramic views of the surrounding landscape, one can see as far as distant Scottish shores from the top of Helen's Tower. La Tour d’Hélène perchée au-dessus des collines de Co Down, est une charmante tours en pierre à trois étages, niché dans les bois du domaine de Clandeboye. Elle est niché sur le toit du monde avec une vue panoramique sur le paysage environnant, on peut voir aussi loin que les rivages écossais à partir du haut de la tour d'Hélène. History: Built in 1848 by Frederick Lord Dufferin, 5th Baron of Dufferin and Ava in honour of his mother Helen Selina Blackwood, Helen's Tower has since been immortalized by Tennyson in the poem of the same name. Designed by architect William Burn and constructed in 1848-1850 as a famine relief project, Helen's Tower helped relieve unemployment at this time. The tower has taken on an unforeseen poignancy, as an almost exact replica of it, the Ulster Tower, was built at Thiepval in 1921 to honour the men of the 36th (Ulster) Division who fell at the Battle of the Somme. Clandeboye Estate was used for army training during the First World War, and the 36th (Ulster) Division trained beside Helen's Tower before leaving for France. -

Luxury Apartments Fashioned for City Life

BELFAST Luxury apartments fashioned for city life Situated opposite the historic Gasworks site in Belfast city centre, Portland 88 is a landmark building comprising 88 luxury “smart”apartments. With easy access and great transport links to Belfast’s Financial Quarter, Ormeau Park, Botanic and Queen’s University, choose an immaculate home and let the location speak for itself. Inner City Beauty Rich in history and steeped with culture, Belfast attracts visitors from near and far. From the vibrant MAC Theatre and St. George’s Market to the iconic Belfast City Hall and Titanic Belfast, this is a city with a story to tell. WWW. PORTLAND 88 .COM Neighbourhood A neighbourhood has been defined as a geographically localised community within a larger city. Portland 88 is entirely this – a place with it’s own distinct identity – somewhere with everything you need to feel at home. WWW. PORTLAND 88 .COM Botanic & the Queen’s Quarter Located in South Belfast and named after Queen’s University, the Queen’s Quarter area is steeped in charm and culture. Whether it’s enjoying a day out at the Ulster Museum, exploring Botanic gardens, or having a coffee in one of the many trendy cafés the area has to offer, there’s plenty to see and do. WWW. PORTLAND 88 .COM Ormeau Road & the Financial Quarter Considered to be one of Belfast’s best-known thoroughfares, the Ormeau Road is brimming with a wide range of businesses and eateries. Yet the beauty of this location stretches even further to the wealth of outdoor spaces including Ormeau Park, River Lagan and the Lagan Towpath. -

Belfast Green and Blue Infrastructure Plan 2020

Belfast Green and Blue Infrastructure Plan 2020 View from Divis looking North East Source: AECOM Belfast Green and Blue Infrastructure Plan 2020 Marshwiggle Way, East Belfast Source: Hunter, N - Belfast City Council provided 4 Belfast Green and Blue Infrastructure Plan 2020 Contents Executive summary 6 Section 5: Principle 3 - Integrated into the urban Section 1: Green and blue infrastructure 8 environment 30 Multifunctional public realm 31 Purpose 8 Multifunctional benefits of SuDS 32 Structure 9 Opportunities for integrating green and blue infrastructure into the What is green and blue infrastructure? 10 public realm 34 Making the most of green and blue infrastructure 12 An example of integrated green and blue infrastructure 36 Section 2: Vision and strategic principles 18 Building integrated green and blue infrastructure 38 Section 3: Principle 1 - Biodiverse 20 Section 6: Principle 4 - Well designed and managed 40 Biodiversity in Belfast 20 Principles of good design and management 42 Opportunities for making Belfast more biodiverse 22 Section 7: Principle 5 - Appropriately funded 44 Section 4: Principle 2 - Planned, interconnected Section 8: Making it happen 45 network 24 Creating a strategic framework for green and blue infrastructure 26 Appendix 1: SuDS typologies 46 Green and blue strategic framework 27 Belfast greenway routes 28 Cover image: Victoria Park, Belfast Source: Sriwastav, S - Belfast City Council provided 5 Belfast Green and Blue Infrastructure Plan 2020 Executive summary Although not all green and blue infrastructure assets will be This is the first Green and Blue Infrastructure Plan for Belfast. delivered and managed primarily for biodiversity, all green It recognises that our vegetated areas (the green) and our 1. -

Board of Governors 17Th Annual Report to Parents 2012/13

6 Glenburn Park, Bangor, Co. Down. BT20 5RG BOARD OF GOVERNORS 17TH ANNUAL REPORT TO PARENTS 2012/13 CONTENTS Page 1. Contents 1 2. Chairman’s Remarks 2 3. Board of Governors 3 4. Principal’s Report 4 5. School Holidays 5 6. Child Protection 6 7. School Aims/Vision/Curriculum/Assessment 7 - 9 8. Musical Events 10 - 11 9. Sporting Activities 12 - 14 11. To Pastures New 15 APPENDIX A. School Accounts 16 - 19 6 Glenburn Park, Bangor, Co Down, BT20 5RG CHAIRMAN’S REMARKS Dear Parent, 2013 is another landmark year for B.P.S., being 60 years since the school opened. Ballyholme has always enjoyed a reputation for high standards in education and I am pleased to say that it remains a school of which we can be proud. As Governors we would like to congratulate the staff and pupils for their achievements in many fields – academic, sporting , music and many others. But most important is the ethos of caring that prevails throughout the school with children respecting one another and all the needs of each pupil being considered by the staff under the leadership of the Principal. Yours sincerely, JENNIFER GRAHAM BOARD OF GOVERNORS Principal: Mr D A Hewitt B.Ed., Dip.Sc. Tel: 028 91270392 Fax: 028 91270158 BOARD OF GOVERNORS 2009 – 2013 Board Representatives:- Cllr P Weir Mrs D Johnston Transferors’ Representatives:- Miss J Graham (Chairman) Mr I Bailie Rev P Lyle (Vice-chairman) Rev S Doogan Parents’ Representatives:- Mrs K Walker Mr N Morrison Teachers’ Representative:- Mrs H McCracken Principal Mr D Hewitt (Hon Secretary) PRINCIPAL’S REPORT The school year began even before the previous one had ended it seemed, as new P1 pupils attended our induction programme in June. -

Orchestral Concerts' Database

Ulster Orchestra Season No.6 1971-1972 f r o m t h e Orchestral Concerts’ Database compiled by David Byers 1 Cover of the 1971-1972 season brochure Original size: 21cm x 30cm The Contents, Players’ List, Malcolm Ruthven’s Foreword and a charmingly written biography of Edgar Cosma have been transcribed on the next four pages. The Database begins on Page 7. 2 CONTENTS Ulster Orchestra Year Book [Season Brochure] 1971-1972 6 Foreword by Malcolm Ruthven Programmes 9 Index to programme listing 10 Repertoire 13 Conductors and Artists 14 Concert Diary 1971-72 17 Ulster Hall Series 19 Belfast Philharmonic Society 20 Country Concerts 23 The Cathedral Consort 24 St. Anne’s Cathedral 25 Northern Bank Sunday Seminars 26 Gala Film Nights 27 Non-Series Concerts 28 Booking Arrangements Profiles 29 Edgar Cosma, Artistic Director and Principal Conductor 30 Alun Francis, Associate Conductor 30 Roland Stanbridge, Leader 31 The Orchestra Staff by Kevin Gannon Articles 32 From the First Bar by Dorothea Kerr 33 1972 Awards 34 Maximisation of Musical Resources by John Murphy 36 Gladiator on the Box by Alun Francis 37 Queen’s University Festival 1972 by David Laing 38 Forty Years Back by Donald Cairns 40 St. Anne’s Cathedral by Dean Crooks 41 Tomorrow’s Musicians by Leonard Pugh 43 Ulster Soloists Ensemble 44 Orchestra Members 46 Ulster Orchestra Association 3 ULSTER ORCHESTRA As at 1 September 1971 (and printed on Page 44 of the Year Book [season brochure] First Violins Flutes Roland Stanbridge Lynda Coffin Mark Butler Anne Bryant Yvonne McGuinness Gerald Adamson -

St Patrick's Day Report 2019

St. Patrick’s Day 2019 – Business Feedback St. Patrick’s Day Business Feedback Report April 2019 0 St. Patrick’s Day 2019 – Business Feedback St. Patrick’s Day Business Feedback Report 2019 *c/o Belfast City Centre Management 2nd Floor Sinclair House 95 – 101 Royal Avenue Belfast BT1 1FE 1 St. Patrick’s Day 2019 – Business Feedback Contents 1. Executive Summary Page 3 Figure One: Map of parade route Page 4 2. Results Pages 4 – 9 Figure Two : Footfall on Sunday 17th March, 2019 Page 5 Figure Three : Sales from St Patricks Day 2019 Page 5 Figure Four: St. Patrick’s Day sales performance comparison 2017 – 2019 Page 6 Figure Five: Do you think the event was inclusive? Page 6 Figure Six: St Patrick’s Day inclusiveness comparison 2017 – 2019 Page 7 Figure Seven: Businesses that witnessed anti-social behaviour comparison Page 7 2017-2019 Figure Eight: Types of anti-social behaviour recorded by businesses Page 8 Figure Nine: Did Retailers believe the event was organised and marshalled Page 9 properly? 3. Year on Year Comparison Pages 10 -11 Figure Ten: Footfall comparative results 2014 - 2019 Page 10 Figure Eleven: Sales comparative results 2014 – 2019 Page 11 Figure Twelve: Survey results comparison 2014 - 2019 Page 11 4. Conclusion and Recommendations Pages 12-13 5. Appendices Pages 14-16 Appendix One: Business Feedback Form Page 14-16 2 St. Patrick’s Day 2019 – Business Feedback 1. Executive Summary 1.1 In March 2019, Belfast City Centre Management undertook a comparative survey of retailers based within the city centre to gauge their opinions on the St. -

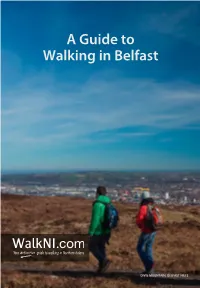

A Guide to Walking in Belfast

A Guide to Walking in Belfast DIVIS MOUNTAIN, BELFAST HILLS M2 Carnmoneynmoney HillHill Carnmoney Hill ± Make the Most of Belfast’s MALLUSK Walking Areas Carnmoney Walking Gems in Belfast BELFAST GLENGORMLEY This walker’s guide will give you information on all the key places to go walking LOUGH B513 in Belfast, so you can couple them with nearby attractions or enjoy them in their B95 M5 own right. A fantastic way to discover the less explored side of the city. Cave Hill Cave Hill From parks blooming with colour to peaceful towpaths providing an alternative way around the city Country Park and breath-taking views across the capital there really is something for everyone when it comes to walking in Belfast. Whether you’ve brought your walking boots or not you can still enjoy a wide range of walks that bring a little slice of countryside to the city. Whilst some routes require a BELFAST Cave Hill reasonable level of fitness there are many other interesting and picturesque walks great for people HILLS Cavehill Country Park Cave Hill with limited mobility and small children. It’s time to add a different element to your city visit and Country Park Divis and the get out and view Belfast from a completely different angle! Black Mountain Titanic Belfast Divis THE BELFAST HILLS PAGE 03 B154 A55 Stormont Black BELFAST Estate The Belfast Hills on the edge of the city tower over the North and West of Belfast and provide Mountain BELFAST BELFAST wonderful hill walking opportunities as well as walks for families and people with limited CITY CENTRE CITY CENTRE HILLS Waterworks mobility. -

Ormeau Park Surgery

ORMEAU PARK SURGERY 281 Ormeau Road, Belfast BT7 3GG Tel (028) 9064 2914 Fax (028) 9064 3993 www.ormeauparksurgery.co.uk The Practice Team Welcome to Our Practice The Doctors Dr Sharon E Gracey (female) MB BCh (QUB 1988) with distinction in Obstetrics and gynaecology, MRCGP DRCOG DCH DGM Dip Family Planning Our aim is to provide our patients with the best possible care within the resources available Special interests - dermatology, minor surgery obstetrics and gynaecology. to us and to deal with any problems as quickly and efficiently as possible. This booklet is to help you get to know about the services we provide. We hope you will find it useful and Dr Cathy A McKeown (female)MB BCh (QUB 2003) with distinction in clinical finals, MRCGP keep it for future reference. DRCOG DCH Dip Family Planning, Certificate in Essential Palliative Care, Dip Practical Dermatology, Letters of Competence in sub dermal contraceptive implants and Diploma in Diabetes Management in Primary Care. Practice History Special interests – family planning. 1893 To 2004 - "Over 100 Years a Doctor's Surgery" Dr Holly Dunlop (female) MBChB (Glasgow 2006) MRCGP DRCOG The medical practice at 281 Ormeau Road was first established in 1893 by Dr J Davidson. Special interests –gynaecology. The house was built as a wedding present for Dr Davidson by his father-in-law. Dr Deborah Collins (female) MBChB BAO 2011 Dr Davidson was succeeded in early 1930 by Dr J Boyd, who subsequently left general practice in 1940 to accept a position as consultant anaesthetist at the Royal Victoria Hospital. The Staff Dr J B Young purchased 281 Ormeau Road and continued practising medicine there until Andrea Lowry - Practice Manager his retirement in 1963 when his assistant Dr J D Henderson became his successor. -

Minutes of Historic Centenaries Working Group of 26 October

30 MEETING OF SPECIAL HISTORIC CENTENARIES WORKING GROUP Minutes of the Special Meeting of Wednesday, 26th October, 2011 Members present: Councillor Hendron (Chairman); Alderman Rodgers; and Councillors Hanna, Kyle, Maskey and Reynolds. Also Attended: Alderman Stalford. In attendance: Mr. A. Hassard, Director of Parks and Leisure; Mrs. H. Francey, Good Relations Manager; Mr. J. Walsh, Legal Services Manager; Mr. C. Campbell, Principal Solicitor; Ms. E. Boyle, Policy and Business Manager; Mr. R. Corbett, Records Manager; and Mr. B. Flynn, Democratic Services Officer. Alderman Stalford At the commencement of the meeting, Alderman Stalford placed on record the fact that he was a member of the Joint Unionist Centenary Committee and was attending the meeting in an advisory capacity. Joint Unionist Centenary Committee The Working Group was reminded that, at its meeting on 17th October, it had considered the following report regarding a request from the Joint Unionist Centenary Committee for the use of Ormeau Park, which had been referred to it by the Parks and Leisure Committee: “1.0 Relevant Background Information Members will be aware that this item was considered by the Parks Committee at its meeting on 15th September and referred to the Centenaries Working Group. The original Unionist Centenary Committee (UCC) request dated 28th August 2011 was to have a parade to Strangford Playing Fields in south Belfast, but at the Council meeting on 3 October this request was amended to refer to Ormeau Park. The original report to the Parks Committee on 15th September contained very little detail since no contact had been made with the UCC at that stage. -

The Lu1sh Oracnr.Cec No

Orienteering Equipment the lU1Sh oracnr.cec www.compasspoint-online.co.uk No. 109 Spring 2005 €1.90 471. 478,1:87 Premium Ou~lilY Conlrol~~.._J..'"Markers Desc Holder souto BOil Gauers MICA, 480 C89 club clothIng :3 sizes lrorn 1:235 Shan 1:4 4 bOllie £12 £18 -- Punchos Sel A or B Long £4.50 2 boUle £9 £26.00 Exceptional Mail Order Service Order by phone, fax K40. G and above £39.50 510 and below 1:34 00 or Online High Street Shop K60S0, 6 and above SO~D OUT Event Shop b', and below SOLD OUT Web Shop Visit our Web Site special offers dept Great deals on Shoes Com~asses t...s, lherm..tll(,f' ~ 1250 Clothing Sist uwm~"op £11.&0 'Xanda thermals Us, IhOrmll1zip rep tl350 K 100 SG 6 and above SOLD OUT SPECTRA MAGNIFIER 5', and below SOLD OUT LHiRH £24.00 ~ ,.~.J.~~~ ;.; '" 19L [cup compass) 8 COMBI 6 NOR lH 6 NOR SPECTRA LH 5 JET £55 00 1S JET 6 JET SPECTRA 1:6.00 c 12-50 £25.00 £29.00 C5950 LHIRH £55.00 . • Vv""I"1J ~) I-s·... l.tow;r;a;:IIumng ",-~, S!:..... .~"' ~n__J, • C·.... ·w L'4 '"71te tJ~' ~ (1--:....0- ~ . ~. )..'.o....,_".."''''''''0 7&~(h,~rtWl~. (Jkoia 10 Market Square, Lytham, CompassPoint Lanes. FY8 5LW Tel 01253795597 .una,..., .orienreerlna-onhne.co.uk Fax 01253 739460 THE IRISH ORIENTEER ADDRESS LIST AJAX ORIENTEERS Peter Keman, 29 Willowbank Park, Rathfamham, Dublln14.(kemanpeter@eircom. che R1Sh oraencecc net) 1 ATHLONE IT ORIENTEERS Nigel Foley-Fisher, AIT, Dublin Rd., Amtone, Co. -

Methodist College Belfast

METHODIST COLLEGE BELFAST ANNUAL PROSPECTUS 2019-2020 CONTENTS PAGE Item Page Contact details 3 School Hours 3 School Holidays 3 Charges 3 Aims and Values 4 The Curriculum 5-11 Curriculum Overview 5 Religious Education 5&11 Organisation of Classes 6 Homework 6 Curriculum Policy 6-7 KS3 8 KS4 (4th and 5th Form) 9 KS5 (6th Form) 9-10 Careers 11&12 Arrangements for Discussing Educational Progress 12 Pastoral Care 13 Learning Support 13 Assessment and Examinations 14-22 KS3 Results 14 GCSE Results 14-16 AS Level Results 17-19 A2 Level Results 20-22 Clubs and Societies Offered in the College 23-26 Overview 23 Before School Activities 24 Lunchtime Activities 25 After School Activities 26 Contribution to the Local and Global Community 27 Facilities 28 Parent teacher Association 29 Admissions 30-35 Admission to Form 1 30-34 Admission to years other than Form 1 34-55 Publication of Policies 36 Charging Policy 37-38 Discretionary Funding 39 Complaints Policy 40-41 Uniform Regulations 42-43 Safeguarding and Child Protection Policy 44-63 Anti-Bullying Policy 64-67 Relationships and Sexuality Education (RSE) 68-72 Substance Mis-use 73-78 ICT Acceptable Use Policy 79-82 Concussion and Other Head Injuries Policy 83-90 2 METHODIST COLLEGE BELFAST Methodist College Belfast seeks to educate its pupils to take their place as young adults in society by providing a safe learning environment in which individual knowledge, capabilities, attitudes and standards of behaviour can be developed and mutual tolerance fostered. This prospectus provides detailed information about the day to day running of the College.