An Account of Striped Façades from Medieval Italian Churches to the Architecture of Mario Botta

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

George Edmund Street

DOES YOUR CHURCH HAVE WORK BY ONE OF THE GREATEST VICTORIAN ARCHITECTS? George Edmund Street Diocesan Church Building Society, and moved to Wantage. The job involved checking designs submitted by other architects, and brought him commissions of his own. Also in 1850 he made his first visit to the Continent, touring Northern France. He later published important books on Gothic architecture in Italy and Spain. The Diocese of Oxford is extraordinarily fortunate to possess so much of his work In 1852 he moved to Oxford. Important commissions included Cuddesdon College, in 1853, and All Saints, Boyne Hill, Maidenhead, in 1854. In the next year Street moved to London, but he continued to check designs for the Oxford Diocesan Building Society, and to do extensive work in the Diocese, until his death in 1881. In Berkshire alone he worked on 34 churches, his contribution ranging from minor repairs to complete new buildings, and he built fifteen schools, eight parsonages, and one convent. The figures for Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire are similar. Street’s new churches are generally admired. They include both grand town churches, like All Saints, Boyne Hill, and SS Philip and James, Oxford (no longer in use for worship), and remarkable country churches such as Fawley and Brightwalton in Berkshire, Filkins and Milton- under-Wychwood in Oxfordshire, and Westcott and New Bradwell in Buckinghamshire. There are still some people for whom Victorian church restoration is a matter for disapproval. Whatever one may think about Street’s treatment of post-medieval work, his handling of medieval churches was informed by both scholarship and taste, and it is George Edmund Street (1824–81) Above All Saints, Boyne His connection with the Diocese a substantial asset for any church to was beyond doubt one of the Hill, Maidenhead, originated in his being recommended have been restored by him. -

William Morris and the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings: Nineteenth and Twentieth Century Historic Preservation in Europe

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Dissertations Graduate College 6-2005 William Morris and the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings: Nineteenth and Twentieth Century Historic Preservation in Europe Andrea Yount Western Michigan University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations Part of the European History Commons, and the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Yount, Andrea, "William Morris and the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings: Nineteenth and Twentieth Century Historic Preservation in Europe" (2005). Dissertations. 1079. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations/1079 This Dissertation-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WILLIAM MORRIS AND THE SOCIETY FOR THE PROTECTION OF ANCIENT BUILDINGS: NINETEENTH AND TWENTIETH CENTURY IDSTORIC PRESERVATION IN EUROPE by Andrea Yount A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History Dale P6rter, Adviser Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan June 2005 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. NOTE TO USERS This reproduction is the best copy available. ® UMI Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: 3183594 Copyright 2005 by Yount, Andrea Elizabeth All rights reserved. INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. -

UWS Academic Portal Business Success and the Architectural

UWS Academic Portal Business success and the architectural practice of Sir George Gilbert Scott, c.1845–1878 McKinstry, Sam; Ding, Yingyong Published in: Business History DOI: 10.1080/00076791.2017.1288216 E-pub ahead of print: 10/03/2017 Document Version Peer reviewed version Link to publication on the UWS Academic Portal Citation for published version (APA): McKinstry, S., & Ding, Y. (2017). Business success and the architectural practice of Sir George Gilbert Scott, c.1845–1878: a study in hard work, sound management and networks of trust. Business History, 59(6), 928-950. https://doi.org/10.1080/00076791.2017.1288216 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the UWS Academic Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 25 Sep 2021 Business Success and the Architectural Practice of Sir George Gilbert Scott, c1845- 1878: a Study in Hard Work, Sound Management and Networks of Trust Sam McKinstry, Ying Yong Ding University of the West of Scotland Tel: 0044-1418483000 Fax: 0044-1418483618 Correspondence: [email protected] 21 December 2016 1 Abstract The study which follows explores the management of Sir George Gilbert Scott’s architectural practice, which was responsible for the very large output of over 1,000 works across the Victorian period. -

The Battle of the Styles in Thomas Hardy's Jude the Obscure

The Battle of the Styles in Thomas Hardy’s Jude the Obscure: Perpendicular, God-seeking Gothicism vs. Horizontally-extended, Secular Classicism Ariyuki Kondo Thomas Hardy’s Architectural Career This paper intends to examine the ways in which the inner worlds of the characters in Thomas Hardy’s Jude the Obscure are depicted through the use of metaphors to reveal the antagonism between Victorian Gothic Revivalism and Victorian Classicism: the Battle of the Styles which Hardy himself had witnessed in his younger days. When Hardy, the son of a stonemason and local builder, first became interested in architecture, ecclesiastical architecture was one of the major areas of work in the building profession. Hardy first became involved in this aspect of architecture in 1856, when he started working for a Dorset-based ecclesiological architect, John Hicks, who designed and restored churches mainly in the Gothic Revival style. In April 1862 Hardy, carrying two letters of recommendation, moved to London. One of these two letters was addressed to Benjamin Ferrey (Pl. 1) and the other to Arthur Blomfield (Pl. 2). Hardy first visited Ferrey. Ferrey had been a pupil of the late Augustus Charles Pugin and knew Pugin’s son, Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin (Pl. 3) who died in 1852 at the age of 40, very well. Ferrey is mostly remembered today for his biography of the Pugins, published in 1861, not long before Hardy’s first visit to him. Ferrey must have been a very well-known architect to Hardy, for it was Ferrey who had designed the Town Hall in Dorchester. -

England's Schools Third Layouts I-31 Evt3q7:Layout 1 21/2/12 08:26 Page 4

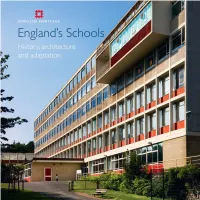

10484 EH England’s Schools third layouts i-31:Layout 1 17/2/12 11:30 Page 1 England’s Schools History, architecture and adaptation 10484 EH England’s Schools third layouts i-31:Layout 1 17/2/12 11:30 Page 2 10484 EH England’s Schools third layouts i-31:Layout 1 17/2/12 11:30 Page 3 England’s Schools History, architecture and adaptation Elain Harwood 10484 EH England's Schools third layouts i-31_EVT3q7:Layout 1 21/2/12 08:26 Page 4 Front cover Published by English Heritage, The Engine House, Fire Fly Avenue, Swindon SN2 2EH Sydenham School, London, additions by www.english-heritage.org.uk Basil Spence and Partners, 1957 (see also English Heritage is the Government’s statutory adviser on all aspects of the historic environment. p 72). [DP059443] © English Heritage 2010 Inside front cover Motif from the Corsham Board School Images (except as otherwise shown) © English Heritage or © Crown copyright. NMR. (Wilts), 1895. [DP059576] First published 2010 Reprinted 2012 Frontispiece One of the best-known adaptations of a ISBN 9781848020313 board school is the very successful Ikon Product code 51476 Gallery, created in 1998 by Levitt Bernstein Associates from Oozells Street School, Birmingham, 1877–8 by Martin and British Library Cataloguing in Publication data Chamberlain. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. [DSC6666] All rights reserved Inside back cover No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or Rugby School (Warwicks) from the air. -

Toledo Cathedral on the International Stage

Breaking the Myth: Toledo Cathedral on the International Stage Review of: Toledo Cathedral: Building Histories in Medieval Castile by Tom Nickson, University Park, Pensylvannia: The Pennsylvania University Press, 2015, 304 pp., 55 col. illus., 86 b.&w. illus., $89.95 Hardcover, ISBN: 978-0-271-06645-5; $39.95 Paperback, ISBN: 978-0-271-06646-2 Matilde Mateo In 1865, the British historian of architecture George Edmund Street (1824-1881) confessed in his Some Account of Gothic Architecture in Spain that he was not expecting to see any example of the great Gothic architecture of the thirteenth century in his first trip to that country until his way back home, when he could set his eyes again on the cathedrals of Chartres, Notre-Dame of Paris, or Amiens. This assumption, however, was shattered when he visited Toledo Cathedral for the first time because this church, to his surprise and in his own words, was ‘an example of the pure vigorous Gothic of the thirteenth century’, and ‘the equal in some respects of any of the great French churches.’ As he admitted, Toledo Cathedral was a startling and pleasant discovery that led him to declare: ‘I hardly know how to express my astonishment that such a building should be so little known [among my compatriots].’1 One has to wonder what would have been Street´s reaction should he have learned that, despite his account and praise of Toledo Cathedral, it would take the astounding length of time of one hundred and fifty years for that gap in knowledge to be filled? Indeed, it has only been recently, in 2015, that a comprehensive monograph in English of Toledo Cathedral has been published. -

Architects, Designers, Sculptors and Craftsmen from 1530

ARCHITECTS, DESIGNERS, SCULPTORS AND CRAFTSMEN FROM 1530 R-Z RAMSEY FAMILY (active c.14) Whittington, A. 1980 The Ramsey family of Norwich, Archaeological Journal 137, 285–9 REILLY, Sir Charles H. (1874–1948) Reilly, C.H. 1938 Scaffolding in the Sky: a semi-architectural autobiography Sharples, J., Powers, A., and Shippobottom, M. 1996 Charles Reilly & the Liverpool School of Architecture, 1904–33 RENNIE, John (1761–1821) Boucher, C.T.G. 1963 John Rennie, the life and work of a great engineer RENTON HOWARD WOOD LEVIN PARTNERSHIP Wilcock, R. 1988 Thespians at RHWL, R.I.B.A. Journal 95 (June), 33–9 REPTON, George (1786-1858) Temple, N. 1993 George Repton’s Pavilion Notebook: a catalogue raisonne REPTON, Humphry (1752–1818), see C2 REPTON, John Adey (1775–1860) Warner, T. 1990 Inherited Flair for Rural Harmony, Country Life. 184 (12 April), 92–5. RICHARDSON, Sir A.E. (1880–1964) Houfe, S. 1980 Sir Albert Richardson – the professor Powers, A. 1999 Sir Albert Richardson (RIBA Heinz Gallery exhibition catalogue) Taylor, N. 1975 Sir Albert Richardson: a classic case of Edwardianism, Edwardian Architecture and its Origins, ed. A. Service, 444–59 RICKARDS, Edwin Alfred (1872–1920) Rickards, E.A. 1920 Architects 1 The Art of E.A. Rickards (with a personal sketch by Arnold Bennett) Warren, J. 1975 Edwin Alfred Rickards, Edwardian Architecture and its Origins, ed. A. Service, 338–50 RICKMAN, Thomas (1776–1841) Aldrich, M. 1985 Gothic architecture illustrated: the drawings of Thomas Rickman in New York, Antiq. J. 65 Rickman, T.M. 1901 Notes of the Life of Thomas Rickman Sleman, W. -

The Journal of William Morris Studies

The Journal of William Morris Studies volume xxi, number 2, summer 2015 Editorial: Why Morris? Patrick O’Sullivan 3 Versions of the Past, Problems of the Present, Hopes for the Future: Morris and others rewrite the Peasants’ Revolt, Julia Courtney 10 Revisiting Morris’s socialist internationalism: reXections on translation and colonialism (with an annotated bibliography of translations of News from Nowhere, 1890–1915), Owen Holland 26 Philip Webb’s visit to Oxford, November 1886, Stephen Williams 53 The Dixton Paintings: vision or dream of News from Nowhere? Patrick O’Sullivan 67 Reviews. Edited by Peter Faulkner 76 William Morris: The Odes of Horace (Facsimile edition), Peter Faulkner 76 Fiona MacCarthy, Anarchy and Beauty: William Morris and his Legacy 1860 – 1960, John Purkis 78 Elizabeth Wilhide, William Morris: Décor & Design, Fiona Rose 81 Wendy Parkins, Jane Morris: the Burden of History, Frank Sharp 84 Mark Frost, The Lost Companions and John Ruskin’s Guild of St George: A Revisionary History, Clive Wilmer 87 Mercia McDermott, Lone Red Poppy, Helena Nielsen 91 the journal of william morris studies . summer 2015 Graham Peel, Alec Miller: Carver, Guildsman, Sculptor, Diana Andrews 94 Joanne Parker & Corinna Wagner, Art & Soul: Victorians and The Gothic, Gabriel Schenk 97 Michael Hall, George Frederick Bodley and the Late Gothic Revival in Britain and America, Peter Faulkner 1o0 Cal Winslow, ed, E.P. Thompson and the Making of the New Left: Essays and Polemics, Martin Crick 105 Alex Prichard, Ruth Kinna, Saku Pinta & David Berry, -

JSAH Manuscript

The British discovery of Spanish Gothic architecture Iñigo Basarrate During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, it was not uncommon for British artists and architects to travel to France and Italy; very few, however, ventured into Spain, which was considered a decadent and dangerous country.1 In contrast, the late eighteenth- and early nineteenth- centuries witnessed a growing number of British travellers to Spain. Spain was, of course, not part of the British colonial agenda, which, according to Edward Said, had driven British scholars' attention to the lands of Islam from the eighteenth-century onwards.2 The increase of British interest in Spain was partly due to the Peninsular War (1808-1814), in which British and Spanish soldiers joined forces against Napoleon’s occupying army.3 The British intellectual interest in Spain was tainted by the increasing Romantic fascination with the 'exotic' that swept across Europe in the early nineteenth-century; in this scenario, many were attracted by the monumental heritage of al-Andalus (the Spanish territories under Islam, 711-1492). Spain with its remarkable Islamic artistic heritage, especially in Granada, Cordoba, and Seville, became attractive as the most accessible place for British travellers to get a flavour of the so-called 'Orient'.4 Although during most of the nineteenth-century, the British fascination for the Alhambra and an idealised Islamic Spain continued, there also arose a growing curiosity for the buildings erected in territories under the gradually expanding Christian rule. This article will focus on the gradual discovery of Spanish Romanesque and Gothic architecture by British architects and architectural historians in the nineteenth century. -

Literature Oxford, He Built Tom Tower, a Rather Florid Gothic Gatehouse

12_D Michael J. Lewis, "The Gothic Revival", London, 2002, pp.13-57,81-93,105-23 it)' with existing buildings. vVren felt that 'to deviate from the old Form, would be to rurn [ a building] into a disagreeable Mixture, which no Person ofa good Taste could relish.' At Christ Church. Chapter 1: Literature Oxford, he built Tom Tower, a rather florid Gothic gatehouse. For the restoration of\Vesmlinster Abbey he made designs for a Gothic facade and transept, intending 'to make the whole of a Piece'. \ Vren also appreciated the structural refinements of the Gothic. At St Paul's, London, the crowning achie\'ement of his .My stud.y holds three thousand volumes classicism, he supported the great barrel va ult of the navc with a AndJet Jsighfor Gothic columns. mighty array of fly ing bu ttresses, although these were carefully Sanderson Miller, 1750 masked from sight behind a blank second-storey wall. Here was the characteristic seventeenth-century attitude toward the It is a leap to go frolll writing poems about ruins to making ruins Gothic: respect and admi ration for its structural achievements, to represent poems, but in the early eighteenth century England horror and disgust for its vi su al fo rms. did just this. The Gothic Revival began as a literary movement. Throughout Europe, simila r attitudes prevailed. Damaged or drawing its im pulses from poetry and drama, an d trans lating dila pidated cathed rals were patched with simplified Gothic ele them in to architecture. It was swept into exis tence in Georgian ments, as at ~ oyon, France in the mid-eighteenth century. -

St. Mary, Church St. Great Shefford

2018 St. Mary, Church St. Great Shefford, Berkshire RG17 7DZ 6 bells, tenor 7cwt-0qr-7lb Grid ref: SU380753 An unusual small church with a round tower sitting on the edge of the river. Wrought iron spiral staircase leads to an anti-clockwise ring. All Saints, Ash Close Brightwalton, Berkshire RG20 7BN 6 bells, tenor 8cwt-1qr-21lb Grid ref: SU427793 Commissioned in 1861 it replaced a much smaller old church. Ground floor ring around the font. St. Mary the Virgin, Church Row, Childrey, Oxfordshire OX12 9PQ 8 bells, tenor 12cwt-0qr-4lb Grid ref: SU359878 12th. c Grade I listed overlooking the Vale of the White Horse. Ancient lead font and a one-handed clock.....another ground floor ring. St. Mary, Church View, Bampton, Oxfordshire OX18 2LW 8 bells, tenor 23cwt-0qr-4lb Grid ref: SP312033 Grade I, 12th.c.church on site of late Saxon Minster, the tower of which survives in the present building with a 13th.c.spire. It is the church featured in 'Downton Abbey'. St. Stephen, Pound Lane, Clanfield, Oxfordshire OX18 2PA 8 bells, tenor 12cwt-3qr-16lb Grid ref: SP283021 A small 13th.c.church with a tower with 4 pinnacles and a squat figure of St. Stephen. 17th.&18th.c. brasses on north wall. All Saints, Church Lane, Coleshill, Oxfordshire SN6 7PT 6 bells, tenor 7cwt Grid ref: SU235937 Grade II*, originally 12th.c.church with 18th.c.box pews in south transept. Fine monument to Sir Henry Pratt (died 1647) & his wife and a pyramidal monument with oval portrait medallion to Viscountess Folkestone (died 1751). -

The General Plan of the William M. Rice Institute and Its Architectural

Architecture at Rice The General Plan of the by Stephen Fox Monograph 29 William M. Rice Institute and Its Architectural Deuelopment fa ifi ifiB ^^ Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from LYRASIS members and Sloan Foundation funding http://www.archive.org/details/generalplanofwilOOfoxs Architecture at Rice The General Plan of the by Stephen Fox Monograph 29 William M. Rice Institute and Its Architectural Development School of Architecture Rice University 1980 ::t ji(nw at Outer .i from Aeftto Contents Acknowledgements iii This issue is dedicated to Ray Watltin Hoagland, Introduction iv daughter of William Ward Watkin, alumna of Rice Institute and 1 Beginnings 1 friend of architecture at Rice. 2 A General Plan 7 3 The Architecture 17 4 First Buildings 31 5 Later Buildings and Projects 53 6 After Cram 75 Notes 83 Bibliography 93 Glossary 95 Index 96 Credits 99 Cover—Administration building, William M. Rice Institute. Houston. Texas. Cram. Goodhue and Ferguson. 1909-1912. Perspective view of east (left) and north elevations. 1912. Copyright © by Stephen Fox and the School of Architecture Rice University Houston. Texas All rights reserved Library of Congress Catalog Card Number; 80-54302 ISBN; 0-938754-00-9 Acknowledgements This study resumes the Architecture at Rice man, former Manager of Campus Business Affairs; monograph series, dormant since 1972. Its publication Guernsey Palmer, Jr. and Ed Samfield of the Office of would not have been possible without the generous Planning and Construction; Mr. and Mrs. Robert A. support of Mr. and Mrs. Nathan Avery and Mrs. Henry Stem; John H. Freeman, Jr., of the firm of Lloyd Jones W.