And 20Th-Century Convents and Monasteries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

George Edmund Street

DOES YOUR CHURCH HAVE WORK BY ONE OF THE GREATEST VICTORIAN ARCHITECTS? George Edmund Street Diocesan Church Building Society, and moved to Wantage. The job involved checking designs submitted by other architects, and brought him commissions of his own. Also in 1850 he made his first visit to the Continent, touring Northern France. He later published important books on Gothic architecture in Italy and Spain. The Diocese of Oxford is extraordinarily fortunate to possess so much of his work In 1852 he moved to Oxford. Important commissions included Cuddesdon College, in 1853, and All Saints, Boyne Hill, Maidenhead, in 1854. In the next year Street moved to London, but he continued to check designs for the Oxford Diocesan Building Society, and to do extensive work in the Diocese, until his death in 1881. In Berkshire alone he worked on 34 churches, his contribution ranging from minor repairs to complete new buildings, and he built fifteen schools, eight parsonages, and one convent. The figures for Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire are similar. Street’s new churches are generally admired. They include both grand town churches, like All Saints, Boyne Hill, and SS Philip and James, Oxford (no longer in use for worship), and remarkable country churches such as Fawley and Brightwalton in Berkshire, Filkins and Milton- under-Wychwood in Oxfordshire, and Westcott and New Bradwell in Buckinghamshire. There are still some people for whom Victorian church restoration is a matter for disapproval. Whatever one may think about Street’s treatment of post-medieval work, his handling of medieval churches was informed by both scholarship and taste, and it is George Edmund Street (1824–81) Above All Saints, Boyne His connection with the Diocese a substantial asset for any church to was beyond doubt one of the Hill, Maidenhead, originated in his being recommended have been restored by him. -

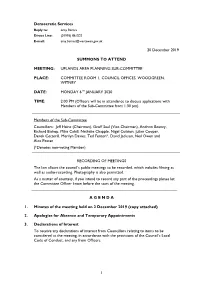

Uplands 06.01.2020

Democratic Services Reply to: Amy Barnes Direct Line: (01993) 861522 E-mail: [email protected] 20 December 2019 SUMMONS TO ATTEND MEETING: UPLANDS AREA PLANNING SUB-COMMITTEE PLACE: COMMITTEE ROOM 1, COUNCIL OFFICES, WOODGREEN, WITNEY DATE: MONDAY 6TH JANUARY 2020 TIME: 2.00 PM (Officers will be in attendance to discuss applications with Members of the Sub-Committee from 1:30 pm) Members of the Sub-Committee Councillors: Jeff Haine (Chairman), Geoff Saul (Vice-Chairman), Andrew Beaney, Richard Bishop, Mike Cahill, Nathalie Chapple, Nigel Colston, Julian Cooper, Derek Cotterill, Merilyn Davies, Ted Fenton*, David Jackson, Neil Owen and Alex Postan (*Denotes non-voting Member) RECORDING OF MEETINGS The law allows the council’s public meetings to be recorded, which includes filming as well as audio-recording. Photography is also permitted. As a matter of courtesy, if you intend to record any part of the proceedings please let the Committee Officer know before the start of the meeting. _________________________________________________________________ A G E N D A 1. Minutes of the meeting held on 2 December 2019 (copy attached) 2. Apologies for Absence and Temporary Appointments 3. Declarations of Interest To receive any declarations of interest from Councillors relating to items to be considered at the meeting, in accordance with the provisions of the Council’s Local Code of Conduct, and any from Officers. 1 4. Applications for Development (Report of the Business Manager – Development Management – schedule attached) Purpose: To consider applications for development, details of which are set out in the attached schedule. Recommendation: That the applications be determined in accordance with the recommendations of the Business Manager – Development Management. -

The Gothic Revival Character of Ecclesiastical Stained Glass in Britain

Folia Historiae Artium Seria Nowa, t. 17: 2019 / PL ISSN 0071-6723 MARTIN CRAMPIN University of Wales THE GOTHIC REVIVAL CHARACTER OF ECCLESIASTICAL STAINED GLASS IN BRITAIN At the outset of the nineteenth century, commissions for (1637), which has caused some confusion over the subject new pictorial windows for cathedrals, churches and sec- of the window [Fig. 1].3 ular settings in Britain were few and were usually char- The scene at Shrewsbury is painted on rectangular acterised by the practice of painting on glass in enamels. sheets of glass, although the large window is arched and Skilful use of the technique made it possible to achieve an its framework is subdivided into lancets. The shape of the effect that was similar to oil painting, and had dispensed window demonstrates the influence of the Gothic Revival with the need for leading coloured glass together in the for the design of the new Church of St Alkmund, which medieval manner. In the eighteenth century, exponents was a Georgian building of 1793–1795 built to replace the of the technique included William Price, William Peckitt, medieval church that had been pulled down. The Gothic Thomas Jervais and Francis Eginton, and although the ex- Revival was well underway in Britain by the second half quisite painterly qualities of the best of their windows are of the eighteenth century, particularly among aristocratic sometimes exceptional, their reputation was tarnished for patrons who built and re-fashioned their country homes many years following the rejection of the style in Britain with Gothic features, complete with furniture and stained during the mid-nineteenth century.1 glass inspired by the Middle Ages. -

Oxfordshire Archdeacon's Marriage Bonds

Oxfordshire Archdeacon’s Marriage Bond Index - 1634 - 1849 Sorted by Bride’s Parish Year Groom Parish Bride Parish 1635 Gerrard, Ralph --- Eustace, Bridget --- 1635 Saunders, William Caversham Payne, Judith --- 1635 Lydeat, Christopher Alkerton Micolls, Elizabeth --- 1636 Hilton, Robert Bloxham Cook, Mabell --- 1665 Styles, William Whatley Small, Simmelline --- 1674 Fletcher, Theodore Goddington Merry, Alice --- 1680 Jemmett, John Rotherfield Pepper Todmartin, Anne --- 1682 Foster, Daniel --- Anstey, Frances --- 1682 (Blank), Abraham --- Devinton, Mary --- 1683 Hatherill, Anthony --- Matthews, Jane --- 1684 Davis, Henry --- Gomme, Grace --- 1684 Turtle, John --- Gorroway, Joice --- 1688 Yates, Thos Stokenchurch White, Bridgett --- 1688 Tripp, Thos Chinnor Deane, Alice --- 1688 Putress, Ricd Stokenchurch Smith, Dennis --- 1692 Tanner, Wm Kettilton Hand, Alice --- 1692 Whadcocke, Deverey [?] Burrough, War Carter, Elizth --- 1692 Brotherton, Wm Oxford Hicks, Elizth --- 1694 Harwell, Isaac Islip Dagley, Mary --- 1694 Dutton, John Ibston, Bucks White, Elizth --- 1695 Wilkins, Wm Dadington Whetton, Ann --- 1695 Hanwell, Wm Clifton Hawten, Sarah --- 1696 Stilgoe, James Dadington Lane, Frances --- 1696 Crosse, Ralph Dadington Makepeace, Hannah --- 1696 Coleman, Thos Little Barford Clifford, Denis --- 1696 Colly, Robt Fritwell Kilby, Elizth --- 1696 Jordan, Thos Hayford Merry, Mary --- 1696 Barret, Chas Dadington Hestler, Cathe --- 1696 French, Nathl Dadington Byshop, Mary --- Oxfordshire Archdeacon’s Marriage Bond Index - 1634 - 1849 Sorted by -

Samuel Lipscomb Seckham

Samuel Lipscomb Seckham By PETER HOWELL l TIL recently the name of Samuel Lipscomb Seckham was fairly widely U known in Oxford as that of the architect of Park Town. A few other facts, such as that he was City Surveyor, were known to the cognoscenti. No-one, however, had been able to discover anything significant about his background, let alone what happened to him after he built the Oxford Corn Exchange in 1861-2. In '970 a fortunate chance led to the establishment of contact with Dr. Ann Silver, a great-granddaughter of Seckham, and as a result it has been po ible to piece together the outline ofhis varied career.' He was born on 25 October ,827,' He took his names from his grandparents, Samuel Seckham (1761-1820) and Susan Lipscomb (d. 18'5 aged 48).3 His father, William ('797-,859), kept livery stables at 20 Magdalen Street, Oxford,. and prospered sufficiently to retire and farm at Kidlington.5 The family came from Devon, where it is aid that Seccombes have occupied Seccombe Farm at Germans week, near Okehampton, since Saxon limes. Seccombes are still living there, farming. It is thought that Seckllam is the earlier spelling, but tombstones at Germansweek show several different versions. 6 It is not known how the family reached Oxford, but Samuel Lipscomb Seckham's great-grandmother Elizabeth was buried at St. Mary Magdalen in 1805.7 His mother was Harriett Wickens (1800-1859). Her grandfather and father were both called James, which makes it difficult to sort out which is which among the various James W;ckens' recorded in I The fortunate chance occurred when Mrs. -

ALBI CATHEDRAL and BRITISH CHURCH ARCHITECTURE TC Albi Cathedral 24/1/2002 11:24 Am Page 2 TC Albi Cathedral 24/1/2002 11:25 Am Page 3

Albi F/C 24/1/2002 12:24 pm Page 1 and British Church Architecture John Thomas TC Albi Cathedral 24/1/2002 11:24 am Page 1 ALBI CATHEDRAL AND BRITISH CHURCH ARCHITECTURE TC Albi Cathedral 24/1/2002 11:24 am Page 2 TC Albi Cathedral 24/1/2002 11:25 am Page 3 ALBI CATHEDRAL and British Church Architecture 8 The in$uence of thirteenth-century church building in southern France and northern Spain upon ecclesiastical design in modern Britain 8 JOHN THOMAS THE ECCLESIOLOGICAL SOCIETY • 2002 TC Albi Cathedral 24/1/2002 11:25 am Page 4 For Adrian Yardley First published 2002 The Ecclesiological Society, c/o Society of Antiquaries of London, Burlington House, Piccadilly, London W1V 0HS www.ecclsoc.org ©JohnThomas All rights reserved Printed in the UK by Pennine Printing Services Ltd, Ripponden, West Yorkshire ISBN 0946823138 TC Albi Cathedral 24/1/2002 11:25 am Page 5 Contents List of figures vii Preface ix Albi Cathedral: design and purpose 1 Initial published accounts of Albi 9 Anewtypeoftownchurch 15 Half a century of cathedral design 23 Churches using diaphragm arches 42 Appendix Albi on the Norfolk coast? Some curious sketches by Sir Giles Gilbert Scott 51 Notes and references 63 TC Albi Cathedral 24/1/2002 11:25 am Page 6 TC Albi Cathedral 24/1/2002 11:25 am Page 7 Figures No. Subject Page 1, 2 Albi Cathedral, three recent views 2, 3 3AlbiCathedral,asillustratedin1829 4 4AlbiCathedralandGeronaCathedral,sections 5 5PlanofAlbiCathedral 6 6AlbiCathedral,apse 7 7Cordeliers’Church,Toulouse 10 8DominicanChurch,Ghent 11 9GeronaCathedral,planandinteriorview -

NORTH OXFORD VICTORIAN SUBURB CONSERVATION AREA APPRAISAL Consultation Draft - January 2017

NORTH OXFORD VICTORIAN SUBURB CONSERVATION AREA APPRAISAL Consultation Draft - January 2017 249 250 CONTENTS SUMMARY OF SIGNIFICANCE 5 Reason for appraisal 7 Location 9 Topography and geology 9 Designation and boundaries 9 Archaeology 10 Historical development 12 Spatial Analysis 15 Special features of the area 16 Views 16 Building types 16 University colleges 19 Boundary treatments 22 Building styles, materials and colours 23 Listed buildings 25 Significant non-listed buildings 30 Listed parks and gardens 33 Summary 33 Character areas 34 Norham Manor 34 Park Town 36 Bardwell Estate 38 Kingston Road 40 St Margaret’s 42 251 Banbury Road 44 North Parade 46 Lathbury and Staverton Roads 49 Opportunities for enhancement and change 51 Designation 51 Protection for unlisted buildings 51 Improvements in the Public Domain 52 Development Management 52 Non-residential use and institutionalisation large houses 52 SOURCES 53 APPENDICES 54 APPENDIX A: MAP INDICATING CHARACTER AREAS 54 APPENDIX B: LISTED BUILDINGS 55 APPENDIX C: LOCALLY SIGNIFICANT BUILDINGS 59 252 North Oxford Victorian Suburb Conservation Area SUMMARY OF SIGNIFICANCE This Conservations Area’s primary significance derives from its character as a distinct area, imposed in part by topography as well as by land ownership from the 16th century into the 20th century. At a time when Oxford needed to expand out of its historic core centred around the castle, the medieval streets and the major colleges, these two factors enabled the area to be laid out as a planned suburb as lands associated with medieval manors were made available. This gives the whole area homogeneity as a residential suburb. -

William Morris and the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings: Nineteenth and Twentieth Century Historic Preservation in Europe

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Dissertations Graduate College 6-2005 William Morris and the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings: Nineteenth and Twentieth Century Historic Preservation in Europe Andrea Yount Western Michigan University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations Part of the European History Commons, and the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Yount, Andrea, "William Morris and the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings: Nineteenth and Twentieth Century Historic Preservation in Europe" (2005). Dissertations. 1079. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations/1079 This Dissertation-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WILLIAM MORRIS AND THE SOCIETY FOR THE PROTECTION OF ANCIENT BUILDINGS: NINETEENTH AND TWENTIETH CENTURY IDSTORIC PRESERVATION IN EUROPE by Andrea Yount A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History Dale P6rter, Adviser Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan June 2005 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. NOTE TO USERS This reproduction is the best copy available. ® UMI Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: 3183594 Copyright 2005 by Yount, Andrea Elizabeth All rights reserved. INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. -

Archdeacon's Marriage Bonds

Oxford Archdeacons’ Marriage Bond Extracts 1 1634 - 1849 Year Groom Parish Bride Parish 1634 Allibone, John Overworton Wheeler, Sarah Overworton 1634 Allowaie,Thomas Mapledurham Holmes, Alice Mapledurham 1634 Barber, John Worcester Weston, Anne Cornwell 1634 Bates, Thomas Monken Hadley, Herts Marten, Anne Witney 1634 Bayleyes, William Kidlington Hutt, Grace Kidlington 1634 Bickerstaffe, Richard Little Rollright Rainbowe, Anne Little Rollright 1634 Bland, William Oxford Simpson, Bridget Oxford 1634 Broome, Thomas Bicester Hawkins, Phillis Bicester 1634 Carter, John Oxford Walter, Margaret Oxford 1634 Chettway, Richard Broughton Gibbons, Alice Broughton 1634 Colliar, John Wootton Benn, Elizabeth Woodstock 1634 Coxe, Luke Chalgrove Winchester, Katherine Stadley 1634 Cooper, William Witney Bayly, Anne Wilcote 1634 Cox, John Goring Gaunte, Anne Weston 1634 Cunningham, William Abbingdon, Berks Blake, Joane Oxford 1634 Curtis, John Reading, Berks Bonner, Elizabeth Oxford 1634 Day, Edward Headington Pymm, Agnes Heddington 1634 Dennatt, Thomas Middleton Stoney Holloway, Susan Eynsham 1634 Dudley, Vincent Whately Ward, Anne Forest Hill 1634 Eaton, William Heythrop Rymmel, Mary Heythrop 1634 Eynde, Richard Headington French, Joane Cowley 1634 Farmer, John Coggs Townsend, Joane Coggs 1634 Fox, Henry Westcot Barton Townsend, Ursula Upper Tise, Warc 1634 Freeman, Wm Spellsbury Harris, Mary Long Hanburowe 1634 Goldsmith, John Middle Barton Izzley, Anne Westcot Barton 1634 Goodall, Richard Kencott Taylor, Alice Kencott 1634 Greenville, Francis Inner -

UWS Academic Portal Business Success and the Architectural

UWS Academic Portal Business success and the architectural practice of Sir George Gilbert Scott, c.1845–1878 McKinstry, Sam; Ding, Yingyong Published in: Business History DOI: 10.1080/00076791.2017.1288216 E-pub ahead of print: 10/03/2017 Document Version Peer reviewed version Link to publication on the UWS Academic Portal Citation for published version (APA): McKinstry, S., & Ding, Y. (2017). Business success and the architectural practice of Sir George Gilbert Scott, c.1845–1878: a study in hard work, sound management and networks of trust. Business History, 59(6), 928-950. https://doi.org/10.1080/00076791.2017.1288216 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the UWS Academic Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 25 Sep 2021 Business Success and the Architectural Practice of Sir George Gilbert Scott, c1845- 1878: a Study in Hard Work, Sound Management and Networks of Trust Sam McKinstry, Ying Yong Ding University of the West of Scotland Tel: 0044-1418483000 Fax: 0044-1418483618 Correspondence: [email protected] 21 December 2016 1 Abstract The study which follows explores the management of Sir George Gilbert Scott’s architectural practice, which was responsible for the very large output of over 1,000 works across the Victorian period. -

Oxford Heritage Walks Book 3

Oxford Heritage Walks Book 3 On foot from Catte Street to Parson’s Pleasure by Malcolm Graham © Oxford Preservation Trust, 2015 This is a fully referenced text of the book, illustrated by Edith Gollnast with cartography by Alun Jones, which was first published in 2015. Also included are a further reading list and a list of common abbreviations used in the footnotes. The published book is available from Oxford Preservation Trust, 10 Turn Again Lane, Oxford, OX1 1QL – tel 01865 242918 Contents: Catte Street to Holywell Street 1 – 8 Holywell Street to Mansfield Road 8 – 13 University Museum and Science Area 14 – 18 Parson’s Pleasure to St Cross Road 18 - 26 Longwall Street to Catte Street 26 – 36 Abbreviations 36 Further Reading 36 - 38 Chapter 1 – Catte Street to Holywell Street The walk starts – and finishes – at the junction of Catte Street and New College Lane, in what is now the heart of the University. From here, you can enjoy views of the Bodleian Library's Schools Quadrangle (1613–24), the Sheldonian Theatre (1663–9, Christopher Wren) and the Clarendon Building (1711–15, Nicholas Hawksmoor).1 Notice also the listed red K6 phone box in the shadow of the Schools Quad.2 Sir Giles Gilbert Scott, architect of the nearby Weston Library, was responsible for this English design icon in the 1930s. Hertford College occupies the east side of Catte Street at this point, having incorporated the older buildings of Magdalen Hall (1820–2, E.W. Garbett) and created a North Quad beyond New College Lane (1903–31, T.G. -

LONDON METROPOLITAN ARCHIVES GAOL DELIVERY SESSIONS at the OLD BAILEY POST-1754 OB Page 1 Reference Description Dates CALENDARS

LONDON METROPOLITAN ARCHIVES Page 1 GAOL DELIVERY SESSIONS AT THE OLD BAILEY POST-1754 OB Reference Description Dates CALENDARS AND INDEXES Calendars of indictments OB/C/J/001 List of Newgate prisoners indicted for trial at the 1754 Oct-1773 Not available for general access Old Bailey Dec Please use microfilm 1 volume X071/037 OB/C/J/002 List of Newgate prisoners indicted for trial at the 1774 Jan-1790 Not available for general access Old Bailey Dec Please use microfilm 1 volume X071/048; X001/182 OB/C/J/003 List of Newgate prisoners indicted for trial at the 1791 Jan-1811 Not available for general access Old Bailey Dec Please use microfilm 1 volume X071/037 OB/C/J/004 List of Newgate prisoners indicted for trial at the 1812 Jan-1824 Not available for general access Old Bailey Jan Please use microfilm 1 volume X071/038 OB/C/J/005 List of Newgate prisoners indicted for trial at the 1824 Apr-1832 Not available for general access Old Bailey Nov Please use microfilm 1 volume X071/038 Calendars of prisoners OB/C/P/001 List of Newgate prisoners awaiting trial at the 1820 Jan 12 Not available for general access Old Bailey -1820 Dec 6 Please use microfilm 1 volume X071/039 Please use microfilm OB/C/P/002 List of Newgate prisoners awaiting trial at the 1821 Jan 10 Not available for general access Old Bailey -1821 Dec 5 Please use microfilm 1 volume X071/039 Please use microfilm OB/C/P/003 List of Newgate prisoners awaiting trial at the 1822 Jan 9 Not available for general access Old Bailey -Dec 4 Please use microfilm 1 volume X071/039 Please use